Policy Memorandum #202

White House Chief of Staff Denis McDonough said that President Obama will lobby lawmakers to give him authority to “fast track” two massive proposed trade deals through Congress: the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) (USTR 2014b) and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) (USTR 2014a). McDonough claimed that the TPP could support $130 billion in “additional exports a year,” and that “each billion dollars in additional trade means 4,000 to 5,000 additional jobs in this country” (CBS News 2014). These economic claims are false: A billion dollars invested in manufacturing here in the United States could support 5,000 jobs, but a billion dollars of increased trade in the form of imported goods from Asia or anywhere else would kill jobs here, rather than supporting them. Projected increased trade by itself tells you nothing about employment impacts: Exports support U.S. jobs, but imports destroy them.

Obama’s push comes despite the fact that Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid has announced his opposition to fast track legislation for these trade deals (Bradner and Raju 2014), as have more than 550 organizations (Citizens Trade Campaign 2014). The public and many members of Congress are catching on to the false promises of so-called free trade.

We’ve heard claims like McDonough’s before. President Obama claimed that the U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement (KORUS) would generate $10 billion to $11 billion in increased exports, supporting “70,000 American jobs from increased exports alone” (The White House 2010). But that is not how it worked out. In fact, in the first year of the agreement U.S. exports to Korea fell, and the trade deficit increased, eliminating more than 40,000 U.S. jobs (Scott 2013a, 2013c).

There are a number of problems with the trade and investment deals being negotiated by the White House. One of the biggest is that these deals make it safe for foreign investors to set up shop in low-wage countries such as Vietnam and Malaysia (two members of the proposed TPP), which encourages outsourcing and rapidly growing imports. It bears repeating that while increased exports can support increases in domestic employment, growing imports cost U.S. jobs (Bivens 2008). If trade and investment deals result in growing trade deficits, job loss and displacement will result, no matter how much overall trade increases.

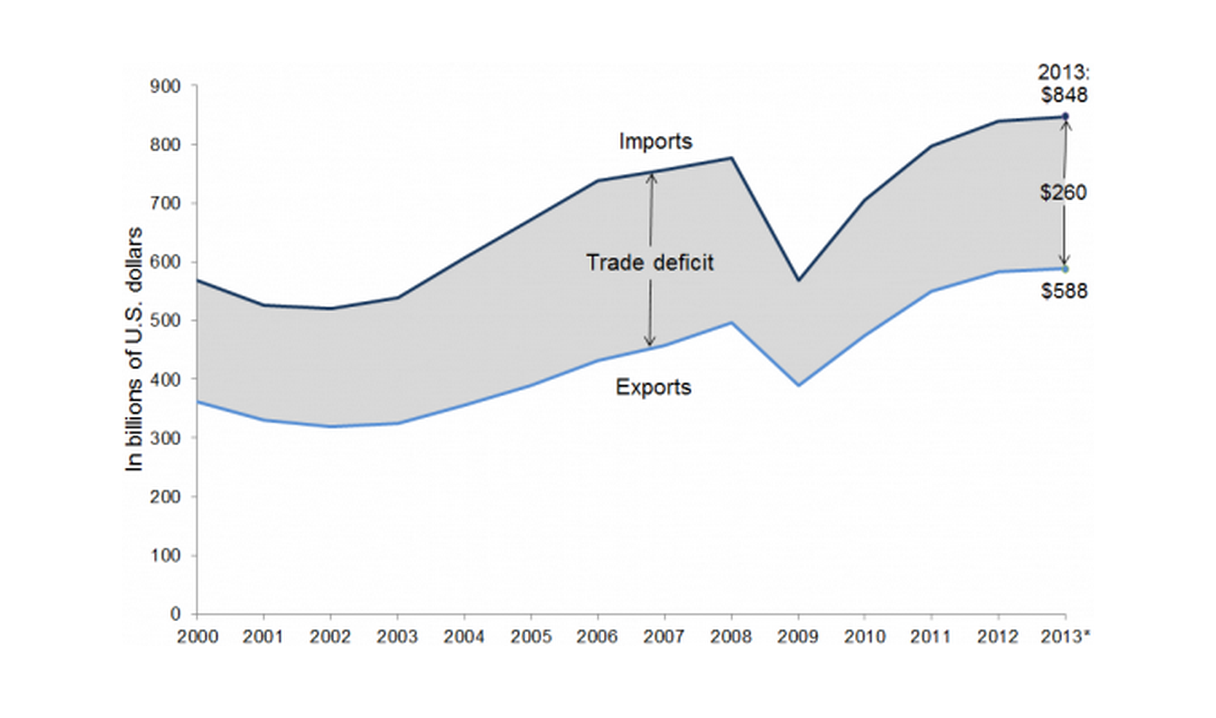

We already know what trade with the TPP countries looks like, and it is nothing like the picture painted by McDonough. The United States had a large trade deficit with the TPP countries, an estimated $260 billion in 2013, as shown in Figure A. Worse yet, the U.S. trade deficit with TPP countries has grown steadily since 2009, increasing 1.4 percent in 2013 alone. However, the U.S. trade deficit with the world fell 6.9 percent in 2013.1 So the TPP countries’ share of the U.S. trade deficit increased from 35.1 percent in 2012 to an estimated 38.2 percent in 2013. We have seen this picture before—it looks a lot like trends under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), only worse (Scott 2013b). We had balanced trade with Mexico and Canada before NAFTA, and a growing trade deficit after. But with the TPP countries, we are starting out far, far behind, with a $260 billion trade deficit.

But that is not all. McDonough also claimed that jobs supported by trade “are paid at somewhere between 15 and 18 percent more than the average wage” (CBS News 2014). That is both misleading and wrong. A recent study showed that workers making exports for China earned only 10.3 percent more than workers in nontraded industries while U.S. workers in industries that competed with goods imported from China earned 29.1 percent more than workers in nontraded industries (Scott 2013d).

Thus, the problems with the trade and investment deals under negotiation include at least two regarding wages, when it comes to trading with China and with many of its neighbors invited to join the TPP. First, wages in the industries that compete against imports pay substantially more than jobs in export industries, so when jobs in export industries replace jobs lost in import-competing industries, jobs paying substantially less replace jobs paying more. Second, between 2001 and 2011, six times as many jobs were displaced by growing imports (3.3 million) due to trade with China as were gained in exporting industries (only 538,000) (Scott 2012b). Most of the workers whose jobs were eliminated by growing imports from China were pitched into unemployment, or into much lower paying jobs in nontraded industries. Thus, we lost far more in wages when imports eliminated U.S. jobs than we gained from increases in the export sector.

So, the United States has a large and growing trade deficit with the TPP countries. Growing trade deficits have displaced nearly 4 million U.S. jobs in the past two decades, since NAFTA took effect in 1994 and since China entered the WTO in 2001, and most of these jobs were good jobs in manufacturing (Scott 2012a and 2012b).

Why then would the White House want to ram new trade and investment deals with Asian countries and with Europe through Congress?

The answer has a lot to do with who benefits from trade and investment deals. The big winners from these deals are multinational companies, and their financiers on Wall Street. Outsourcing is extremely profitable for big business. Foreign direct investment (FDI) in Mexico tripled after NAFTA took effect (Scott 2012a). U.S. multinational corporations chose to build billions of dollars worth of new plants and infrastructure in Mexico rather than in the United States. After China entered the WTO, it became the largest recipient of FDI of all developing countries, and the third largest recipient in the world (behind the United States and the United Kingdom) (Scott 2012b).

So, the next time someone from the White House makes outlandish and one-sided claims about the benefits of the TPP or the proposed TTIP with Europe, he or she should be asked about the effects on imports, foreign direct investment, and outsourcing. More important, we must query the net effects of those deals on jobs, wages, and worker income, especially for production workers who make up 70 percent of the labor force (Bivens 2013a).

Finally, it is also important to ask who wins from these trade deals, and who is lobbying for them (Scott 2014). Multinational businesses, their executives, their billionaire owners, and their financiers on Wall Street pour massive amounts of cash into the campaign coffers of both parties, and of many members of Congress. They expect results for their money. Trade and investment deals like NAFTA, KORUS, and China’s entry into the WTO were at the top of their wish lists.

Public officials should be held accountable for assertions that trade and investment deals create jobs, or that they will generate higher wages in the United States. Experience with NAFTA, KORUS, and China have shown that these deals cost jobs and depress wages in the United States. They have also contributed to rising corporate profits and growing inequality (Bivens 2013a and 2013b). Public opinion polls show that NAFTA-style deals are increasingly unpopular (Public Citizen 2012). Senator Reid has reached a wise decision to table discussion of fast track legislation for these trade deals, and the White House should reserve its scarce political capital for addressing the jobs crisis by any and all means.

—Robert E. Scott is director of trade and manufacturing policy research at the Economic Policy Institute. He joined EPI as an international economist in 1996. Before that, he was an assistant professor with the College of Business and Management of the University of Maryland at College Park. His areas of research include international economics and trade agreements and their impacts on working people in the United States and other countries, the economic impacts of foreign investment, and the macroeconomic effects of trade and capital flows. He has a Ph.D. in economics from the University of California-Berkeley.

‒The author thanks Ross Eisenbrey for comments and William Kimball for research assistance

References

Bivens, Josh. 2008. Trade, Jobs and Wages. Economic Policy Institute Issue Brief #244. http://www.epi.org/publication/ib244/

Bivens, Josh. 2013a. “Slow Wage-Growth Just One More Sign of How Big a Problem the Profit-Biased Recovery Is.” Working Economics (Economic Policy Institute blog). August 23. http://www.epi.org/blog/slow-wage-growth-sign-big-problem-profit/

Bivens, Josh. 2013b. Using Standard Models to Benchmark the Costs of Globalization for American Workers without a College Degree. Economic Policy Institute Briefing Paper #354. http://www.epi.org/publication/standard-models-benchmark-costs-globalization/

Bradner, Eric, and Manu Raju. 2014. “Harry Reid Rejects President Obama’s Trade Push,” Politico. January 29. http://www.politico.com/story/2014/01/harry-reid-barack-obama-trade-deals-102819.html

CBS News. 2014. “Transcript: Major Garrett Interviews White House Chief of Staff Denis McDonough.” February 2. http://www.cbsnews.com/news/transcript-major-garrett-interviews-white-house-chief-of-staff-denis-mcdonough/

Citizens Trade Campaign. 2014. “Over 550 Groups Urge Opposition to Fast Track.” http://www.citizenstrade.org/ctc/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/FastTrackOppositionLtr_012714_Congress.pdf

Public Citizen. 2012. “Public Opinion Polling Shows NAFTA-style Trade Deals Becoming Even More Unpopular.” Public Citizen. http://www.citizen.org/documents/memo-us-polling-shows-nafta-style-trade-deals.pdf

Scott, Robert E. 2012a. Heading South: U.S.-Mexico Trade and Job Displacement after NAFTA. Economic Policy Institute Briefing Paper #308. http://www.epi.org/publication/heading_south_u-s-mexico_trade_and_job_displacement_after_nafta1/

Scott, Robert E. 2012b. The China Toll: Growing U.S. Trade Deficit with China Cost More than 2.7 Million Jobs between 2001 and 2011, with Job Losses in Every State. Economic Policy Institute Briefing Paper #345. http://www.epi.org/publication/bp345-china-growing-trade-deficit-cost/

Scott, Robert E. 2013a. “Free Trade Agreements Have Hurt American Workers.” Economic Policy Institute Infographic, July 18. http://www.epi.org/publication/infographic-free-trade-agreements-have-hurt-american-workers/

Scott, Robert E. 2013b. NAFTA’s Legacy: Growing U.S. Trade Deficits Cost 682,900 Jobs. Economic Policy Institute Economic Snapshot. http://www.epi.org/publication/nafta-legacy-growing-us-trade-deficits-cost-682900-jobs/

Scott, Robert E. 2013c. No Jobs from Trade Pacts: The Trans-Pacific Partnership Could Be Much Worse than the Over-Hyped Korea Deal. Economic Policy Institute Briefing Paper #369. http://www.epi.org/publication/trade-pacts-korus-trans-pacific-partnership/

Scott, Robert E. 2013d. Trading Away the Manufacturing Advantage: China Trade Drives Down U.S. Wages and Benefits and Eliminates Good Jobs for U.S. Workers. Economic Policy Institute Briefing Paper #367. http://www.epi.org/publication/trading-manufacturing-advantage-china-trade/

Scott, Robert E. 2014. “Who Wins From Trade?” Working Economics (Economic Policy Institute blog). January 31. http://www.epi.org/blog/wins-trade/

USITC (U.S. International Trade Commission). 2014. Interactive Tariff and Trade DataWeb. http://dataweb.usitc.gov/

USTR (Office of the U.S. Trade Representative). 2014a. “Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP).” http://www.ustr.gov/ttip

USTR (Office of the U.S. Trade Representative). 2014b. “Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).” http://www.ustr.gov/tpp

The White House. 2010. “The U.S.-South Korea Free Trade Agreement: More American Jobs, Faster Economic Recovery through Exports” (fact sheet). http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/fact_sheet_overview_us_korea_free_trade_agreement.pdf

Endnotes

1. Author’s analysis and USITC (2014).