The March Employment Situation report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics showed the jobs recovery unmistakably gaining traction, with the addition of 216,000 jobs and the unemployment rate ticking down to 8.8% as more unemployed people found work. But the labor force participation rate held steady at its lowest point of the recession (and its lowest point in 27 years) meaning that the millions of workers who dropped out of (or never entered) the labor force during the downturn continue to wait on the sidelines, not yet optimistic enough about the prospect of finding a job to begin looking for work. All in all, however, the BLS March report shows extremely welcome momentum in the labor market. The reality check to this report is the larger context—given the size of the gap in the labor market, even at March’s job growth rate it would still take until around 2018 to get back to the prerecession unemployment rate. In other words, as a snapshot, this report looks quite good, but given where we are, we need to see job gains of this magnitude and much more in the coming months.

The labor force, unemployment, and the employment-to-population ratio

The labor force participation rate held steady at 64.2% in March. Despite payroll job growth over the last year, the labor force is still smaller than it was a year ago (by more than a half-million workers), though the working-age population grew by 1.9 million over the last year. Consequently, the proportion of the population in the labor force is now 0.7 percentage points below where it was a year ago. If the labor force participation rate had held steady over the last year, there would be roughly 1.7 million more workers in the labor force right now. Instead, those would-be workers are on the sidelines. If these workers were in the labor force and were unemployed, the unemployment rate would be 9.8% instead of 8.8%. In other words, the improvement in the unemployment rate over the last year (from 9.7% to 8.8%) is due to would-be workers deciding to sit out.

Some have claimed that the labor force participation rate has potentially been permanently changed, and that these missing workers may never come back. It is far too soon to draw conclusions on that front. There remain five unemployed workers per available job—a far worse ratio than the worst month of the early-2000s recession. In this environment, where the chances of an unemployed worker finding a job are extremely low, the fact that the sidelined workers are not yet reentering in search of work is no surprise.

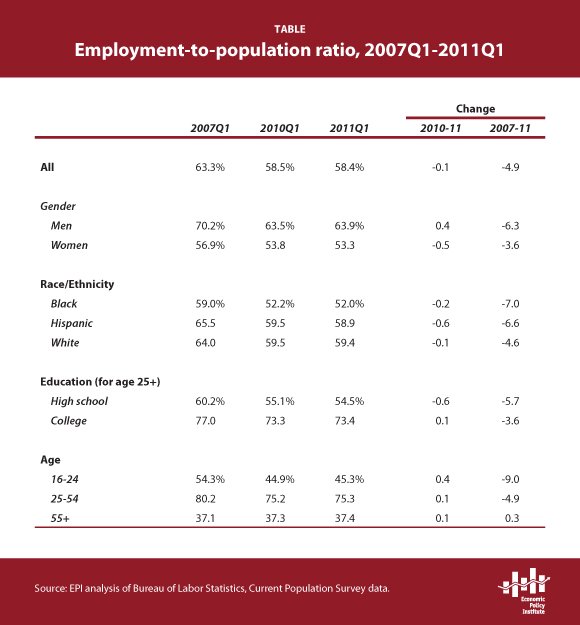

At a time like this, with the labor force not growing at a steady pace, we should turn to measures other than the unemployment rate to get a sense of how the labor market is evolving. The most basic measure is the employment-to-population ratio, which simply is the share of the working age population that has a job. This measure increased slightly in March, from 58.4% to 58.5%. However, it has declined slightly over the last year, from 58.6% to 58.5%.

Most demographic groups have not experienced substantial changes in their employment-to-population ratio over the last year. As shown in the Table, men have seen a modest improvement of 0.4 percentage points over the last year, but they remain 6.3 percentage points below where they were four years ago. Women on the other hand have seen a decline of 0.5 percent points, and they remain 3.6 percentage points below where they were four years ago. Hispanic workers have declined by 0.6 percentage points over the last year, and they remain 6.6 percentage points below where they were four years ago. High-school educated workers have declined by 0.6 percentage points over the last year, and they remain 5.7 percentage points below where they were four years ago. Young workers (workers age 16-24) have seen a 0.4 percentage point increase in their employment-to-population ratio over the last year, but they are coming off a huge drop and remain 9.0 percentage points below where they were four years ago. Older workers (55+) are the one age group that has seen modest growth; they are 0.3 percentage points above where they were four years ago.

Hours and earnings

The length of the average workweek held steady in March at 34.3 hours. Average hours have grown only two-tenths of an hour over the last year, and have thus far made up just two-thirds of average work hours lost in the first 18 months of the downturn (the low point was 33.7 hours in June 2009). The fact that hours are still far below where they were before the recession started belie the claim that businesses aren’t hiring due to uncertainty about (or burdens of) laws like health care or regulatory reform; if businesses had work to be done but didn’t feel they could hire new workers, they would strongly ramp up their current workers’ hours, which isn’t happening. In other words, the hours data show that regulatory burdens are not keeping businesses from hiring, a lack of demand is.

Average hourly wages were flat in March, and have grown at a 1.8% annualized rate over the last three months and a 1.7% rate over the last year. Given that wages and hours didn’t budge, weekly wages were also flat in March.

Long-term unemployment

The share of unemployed workers who have been unemployed for more than six months increased slightly in March, from 43.9% to 45.5%, approaching the all-time high of 45.6% last May. There remain 6.1 million workers who have been unemployed for longer than six months. These dramatic figures are unsurprising given the depth and severity of the Great Recession compared with prior recessions.

Industry sectors

The public sector again displayed the ongoing drag of state and local budget problems, with state government employment remaining flat and local government employment dropping by 15,000. Since their employment peak in August 2008, state and local governments have shed nearly half a million jobs.

The private sector added 230,000 jobs. Of these gains, 199,000 were in private service-providing industries and 31,000 were in goods-producing industries. Manufacturing gained 17,000 jobs, another month of positive news but not as strong as the 32,000 average of the prior three months. Construction declined by 1,000 in March, not far below the 4,000 average gain of the prior three months.

Temporary help services increased by 29,000, compared with a 22,000 average over the prior three months. While temp help has generally increased over the last year and a half, it is still far below where it was before the recession because it lost so much in the first 18 months of the downturn. Employment in temporary help services is now 11.5% below where it was in December 2007, compared with -6.1% for total private employment. The fact that temporary help is still so far behind also belies the claim that businesses aren’t hiring right now due to uncertainty about (or burdens of) laws like health care or regulatory reform; if businesses had work to be done but didn’t feel they could hire new workers, they would be making much more use of temporary help services.

Employment in restaurants and bars increased in Marc

h (+27,000), compared with a 16,000 average over the prior three months. Employment in retail trade increased by 18,000 in March, compared with a 10,000 average over the prior three months. Health care added 37,000 jobs, also an increase over the 25,000 jobs added on average in the prior three months.

Underemployment

The underemployment rate (i.e., the U-6 measure of labor underutilization) is a more comprehensive measure of labor market slack than the unemployment rate because it includes not just the officially unemployed but also jobless workers who have given up looking for work and people who want full-time jobs but have had to settle for part-time work. (Note, however, it does not include people who are underemployed in the sense that they have had to take a job that is below their skills, training, or experience level.) This measure improved in March, to 15.7%, due to a decline in the number of unemployed (-131,000) and a substantial decline in the number of marginally attached (-295,000). The number of involuntary part-time workers increased by 93,000. In March a total of 24.5 million workers were either unemployed or underemployed, still nearly double from 12.9 million in 2007.

Conclusion

In the first quarter of 2011, the labor market added 159,000 jobs per month on average. This is relatively strong growth—in the fourth quarter of 2010 it gained 139,000 per month on average and in the first three quarters of 2010 it gained just 58,000 per month on average. However, the labor market remains 7.2 million payroll jobs below where it was at the official start of the recession three years and three months ago. And this number vastly understates the size of the gap in the labor market by failing to account for the additional 3.9 million jobs needed over this period to keep up with the growth in the working-age population. This means the labor market is now 11.1 million jobs below the level needed to restore the prerecession unemployment rate (5.0% in December 2007). To achieve the prerecession unemployment rate in three years, the labor market would have to add around 400,000 jobs every month for that entire period.

Nicholas Finio provided research assistance.