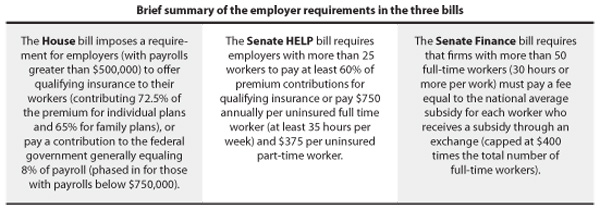

All three of the leading health reform bills in Congress include some sort of employer mandate to either provide health insurance to employees or pay a fee. But since these employer requirements are vastly different in each bill, they will be effective to varying degrees at raising revenue and ensuring the stability and quality of coverage, arguably the two main objectives of any reform bill. The structure of the employer requirement will also help determine how efficiently it can be administered and enforced and what unintended labor market consequences may result.

This piece examines each of these issues as they apply to each of the three competing health reform bills and finds that the Affordable Healthcare for America Act, which the House of Representatives approved November 7, is the most effective at raising revenue and encouraging employers to continue offering insurance thereby allowing people to keep the insurance they have. The House bill also minimizes administrative costs and labor market distortions.

Generating revenue. The employer requirement in the House bill is projected to raise $135 billion over the 10-year window, two-and-a-half times more than the $52 billion expected from the Senate HELP bill and over five times the $23 billion expected from the Senate Finance bill. The House bill wins.

Encouraging employers to continue to provide coverage. The share of non-elderly adults with job-based coverage has fallen steadily over the past decade. The requirements in the House bill provide a fairly effective incentive to encourage employers to continue to provide coverage, with the exception of those where the majority of employees are low-income (below 200% of the federal poverty level for individuals, and 250% for families.)

The employer requirement in the HELP bill, by contrast, is too small to have a significant impact on employer’s decision to provide coverage or pay into the exchange: the $750-a-year penalty in the HELP bill compares to an average cost of $13,122 for a family health insurance plan.

The employer penalty in the Senate Finance Committee bill would likewise be ineffective in providing an incentive for employers to retain coverage. For employers with largely low-wage work forces, the penalty for not covering an employee is too small to discourage employers from dropping coverage. The penalty per subsidized worker is greatest for employers with a small share of workers who would be eligible for subsidies. But employers fitting that profile—those with a large portion of higher-wage workers—already have many reasons, including favorable tax benefits, to provide coverage to their workers. As discussed below, employers can easily evade the requirement by reducing workers’ hours below 30 a week. The House bill wins.

Maintaining standards for employer-sponsored insurance: All three bills require employer-sponsored plans to have annual out-of-pocket caps and no limit on maximum lifetime benefits. However, both Senate bills do not extend those requirements to employers that are self-insured, effectively excluding 57% of the workers who have employer coverage. The House bill wins.

Administrative costs: The employer requirement in the Senate Finance Committee bill is the most complicated and costly to administer. Under the House bill and the HELP bill, employers could determine their required payment amount based on information that is readily available to them such as the size of their payroll, the number of employees, and whether or not they offer employees coverage that meets the basic standards. The HELP provision also requires information on work hours. But the penalties in the Senate Finance Committee Bill are based on information that the employer does not have access to: employees’ household income and eligibility for subsidies in the exchange. Employers would need to be billed after the fact from the exchange. That would be costly for the exchange to administer and create greater uncertainty for the employer. The House bill wins.

Labor market distortions: None of the requirements in the House bill are expected to have any significant impact on employment. Most economists believe that for workers earning above the minimum wage, the cost of coverage would be passed onto workers in the long run in the form of reduced wages or other forms of compensation. The cost of complying with the House bill would be equivalent to a modest increase in the minimum wage. Studies of employer mandates adopted in Hawaii and San Francisco found no evidence of an impact of those requirements on employment.

The effect of the Senate Finance Committee bill would be concentrated among workers whose wages are less likely to be able to adjust, which the Congressional Budget Office says would result in a larger employment effect than the more broad-based House approach.

Furthermore, the Senate Finance Committee requirement is likely to encourage a shift toward a more part-time workforce in order to avoid the penalty. Studies of Hawaii’s health insurance mandate have found that the state has a disproportionate number of employees working slightly under 20 hours a week, the number of hours at which that requirement becomes effective. The 30-hour cut-off in the Senate Finance bill is more likely to encourage reductions in work time, since it is easier to restructure work to fewer than 30 hours a week than to fewer than 20 hours a week. Work shifts in this range are common in the restaurant, retail, and nursing home industries.

The House wins.

Elise Gould is EPI’s Director of Health Policy Research. Ken Jacobs is Chair of the Center for Labor Research and Education at University of California, Berkeley.