EPI Senior Economist Adam S. Hersh submitted the following written testimony to the U.S. International Trade Commission regarding Investigation No. 332-600,“USMCA Automotive Rules of Origin: Economic Impact and Operations, 2025 Report.”

Dear Commissioners:

Thank you for the opportunity to comment on the upcoming 2025 Report on the USMCA Automotive Rules of Origin. Although these rules are only really beginning to come into effect, it is already clear that the incremental tightening—along with the labor Rapid Response Mechanism—are insufficient to overcome the fatal flaws in the NAFTA model that allowed multinational producers to threaten and actually relocate work to lower-wage and more readily exploitable places like Mexico. i Thirty years after the start of NAFTA, this corporate strategy is still suppressing wages for motor vehicle and parts workers and their communities in all 3 countries. USMCA has done little to change this equation and the updated Rules of Origin (ROOs) seem unlikely to change the course dwindling job quality and quantity in the U.S. motor vehicles and parts industries.

ROOs are too leaky to ensure high quality jobs

Even before the 2023 “rolling up” decision, USMCA’s content rules were too porous and the labor value standard too low to achieve the competitive North American automotive industry with high quality jobs that we all want. The rules allow non-originating content to be magically transformed into originating content and creep into North American supply chains with duty-free market access, even when that content is produced with illegal subsidization and exploited workers in third countries. Leakage from USMCA’s ROOs undercuts all North American workers by pitting them against non-USMCA producers who have not made the same commitments to worker, environmental, and consumer safety standards, and have not extended reciprocal market access to similar North American producers.

The porous rules have a number of implications: First, the more complicated an intermediate auto part is – i.e., the more underlying, lower-tier components are required to make an intermediate part – the more foreign content can masquerade as “Made in North America.” Even under USMCA RVC calculations, substantial non-originating content will enter at 0% duty. Thus, non-originating content qualifying for USMCA ROOs can expand at an exponential rate.

Second, the core parts list omits critical new technology goods for electric vehicle related components and autonomous vehicle related components. Fortunately, USMCA Article 3.10 provides a mechanism for the parties to expand the list of core components covered by North American content rules, though this is not a foregone conclusion and, in the meantime, content leakages deter the establishment of North American competition to illegally-subsidized and market-dominant Chinese technologies. The faster the industry evolves, the more vehicle content will be uncovered by USMCA ROOs.

Third, for most places in the United States $16/hour is at or near a poverty wage, on par with fast food and other low-skilled service wages. But because President Trump did not negotiate an inflation adjustment, already the Labor Value Content wage has declined 21% in real terms since he signed USMCA into law. And this wage floor—which will continue eroding into complete irrelevance before Mexican wages converge on U.S. and Canadian wages—covers less than half of a vehicle’s content, meaning it is not a meaningfully binding wage standard.

Finally, not only did USMCA leave these gaping holes for non-originating content, but the agreement largely relies on these same corporate entities to self-certify their compliance with the ROO regime. This creates a clear incentive and opportunity for manufacturers to cheat compliance. The less government monitors and enforces these rules, the more incentive manufactures have to evade USMCA ROOs.

In order to improve upon these shortcomings, USTR in conjunction with the Departments of Labor, Treasury, and Commerce should maintain a real-time database of facilities certified and in compliance with all USMCA ROOs for parts content, labor value, and primary metals content. Congress should establish the capacity to investigate whether duty-free treatment for a vehicle was provided due to errors or omissions in the producer’s certifications or preference claims, and to claw back duties with penalties when found in violation. What’s more, U.S. agencies should be required affirmatively to notify the Secretary of the Treasury of any malfeasance or whistleblower violation in response to reporting fraud, in the ROO calculations, so that duty-free treatment could be revoked.

The impact of loose ROOs

Rather than working to retain production in the United States with incentives for high-quality work, the trade data already show a widening U.S. bilateral automotive trade deficit with Mexico since USMCA’s inception.

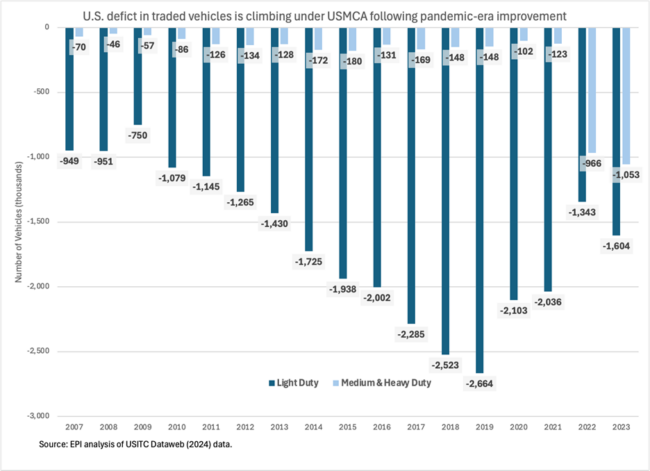

Figure 1 shows that U.S. deficit in vehicles traded with Mexico is climbing under USMCA. For light duty vehicles—passenger cars and light pickup trucks—the U.S. deficit improved moderately after 2019 with the onset of the pandemic, automotive supply-chain shortages, and shifts in demand toward higher-value vehicles—more of which are produced in the United States. As a result, the light duty vehicle deficit was cut nearly in half by 2022. In 2023, with a strengthened U.S. economic recovery, even into the headwinds of U.S. monetary policy tightening, the light duty vehicle deficit began climbing once again. For medium- and heavy-duty vehicles, Figure 1 shows that prior to USMCA the U.S. maintained a small-but-steady trade deficit with Mexico. But that all changed with USMCA: the trade deficit jumped to more than 1 million trucks by 2023 from just 123,000 trucks in 2020.

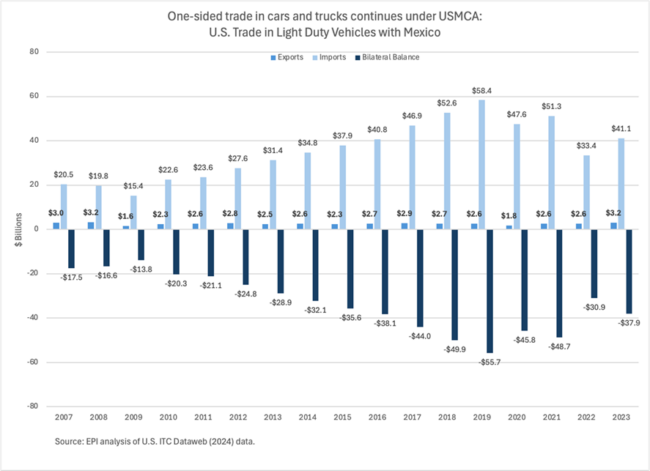

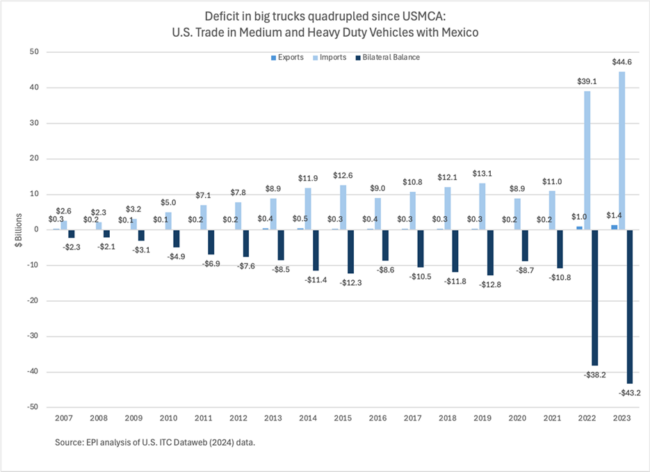

In U.S. dollar terms, the bilateral U.S. trade deficit with Mexico in light-duty vehicles reached a pre-pandemic business cycle peak of nearly $56 billion in 2019 (Figure 2). As the U.S. economy has recovered, the light-duty trade deficit is climbing once again, to $40 billion 2023. The deficit in medium- and heavy-duty trucks, which averaged less than $9 billion annually in the pre-pandemic business cycle expansion jumped to $38 billion in 2022 and $43 billion in 2023 (Figure 3).

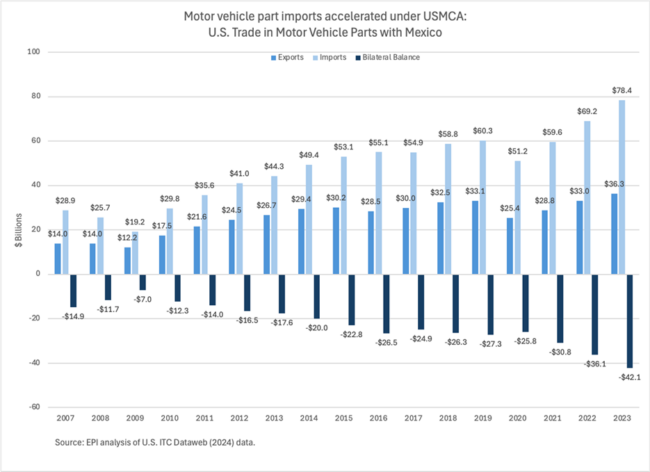

A similar pattern can be seen in U.S.-Mexico bilateral trade in motor vehicle parts. Parts imports from Mexico showed a steadily increasing trend over the pre-pandemic business cycle, from a $7 billion deficit in 2009 to a $27 billion deficit by 2019 (Figure 4). These data cover trade in tariff codes for motor vehicle parts specified by the ITA. ii However, since the onset of USMCA, U.S. vehicle producers have gone on a shopping spree for parts from Mexico. In just three years, U.S. imports shot up to $78 billion annually from $51 billion and the parts deficit ballooned to $42 billion from $26 billion.

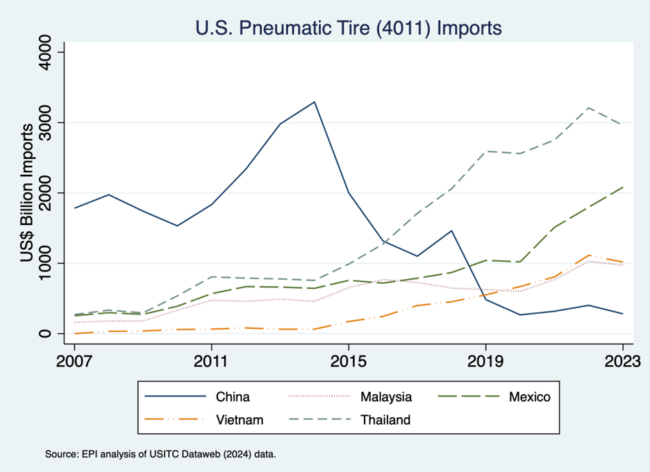

Widening trade deficits in vehicles and parts with Mexico reflect motor vehicle producers’ preference to sight more of the North American industry in low-wage manufacturing centers, despite tighter USMCA ROOs. But they also reflect a realignment of global automotive supply chains following 2018 U.S. Secs. 301 and 232 tariffs and a slate of antidumping and countervailing duty determinations as production and trade was rapidly reorganized to third countries. A key example of this phenomenon can be seen in the case of tire imports to the U.S. (Figure 5). In anticipation of and following ITC determinations of injury from Certain Passenger Vehicle and Light Truck Tires from China in 2015, Chinese tire manufacturers quickly expanded offshore in countries like Thailand and Vietnam, among others, substituting for Chinese production for U.S. markets.iii As a result, tire imports from these countries surged and led to subsequent ITC import injury investigations from these countries.iv

Increasing Chinese penetration of North American motor vehicle supply chains

USMCA is not equipped to handle the coming influx of automotive content originating with Chinese-owned and Chinese-affiliated firms—often the beneficiaries of robust, illegal government subsidization and regulatory forbearance. In the aftermath of U.S. tariffs and trade enforcement measures, Chinese-owned and Chinese-affiliated firms have been repositioning their global footprint to launder the origins of their production chains through countries with more favorable tariff treatment in U.S. and North American markets. Following trends in other industries including steel and aluminum products, production chains oriented around Chinese-owned and -affiliated firms are rapidly penetrating North American automotive supply chains with growing manufacturing platforms in Mexico and a range of third countries with surging auto parts exports to the U.S.

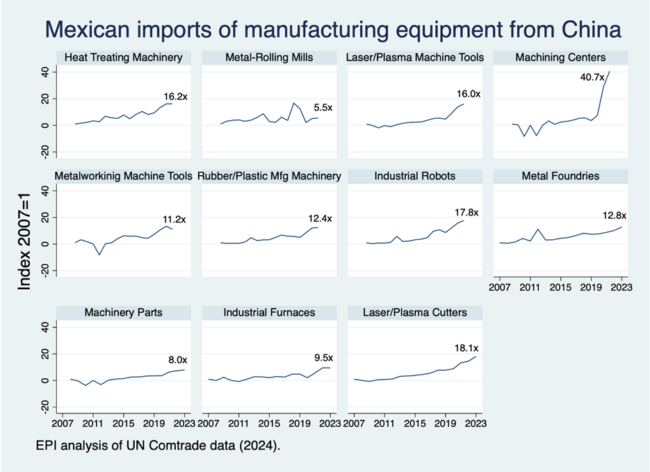

China’s ballooning outward direct investment position since 2018 indicates a rapidly expanding overseas footprint for production organized around Chinese value chains. Since 2018, Chinese outward FDI positions increased by 126% in Mexico, 40% in Thailand, 246% in India, 119% in Vietnam, 97% in Malaysia, 73% in Indonesia, and 12% in the Philippines—in total a $42 billion expansion.v At the same time, exports of Chinese-made manufacturing machinery and equipment to these emerging automotive production hubs has surged since 2017: 134% to Mexico, 92% to Thailand, 79% to India, 149% to Vietnam, 159% to Malaysia, 119% to the Philippines, and exponentially to Indonesia.

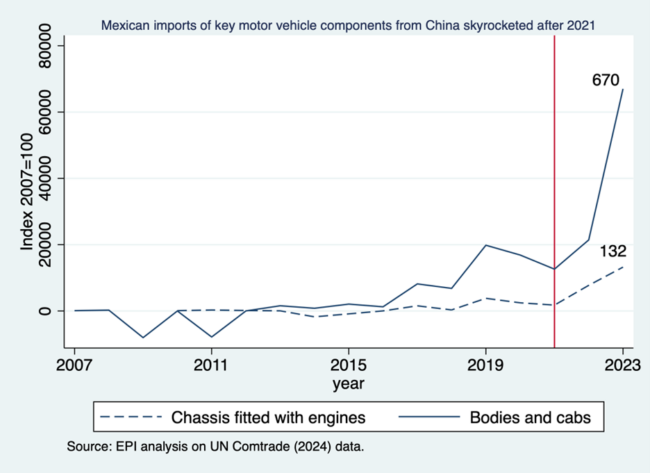

For Mexico, depending on the kind of machinery, this has meant an 8-fold to 41-fold increase of manufacturing equipment imports from China (Figure 6). Among this wave of manufacturing investment are significant projects to establish platforms in Mexico for Chinese motor vehicle and parts producers aiming to penetrate the USMCA market.vi Mexican imports of Chinese core parts—chassis fitted with engines and bodies and cabs—have increased 132-times and 670-times, respectively, over the previous business cycle.

These examples illustrate the tip of the iceberg for the potential of state-supported Chinese content to penetrate North American markets. While imports of complete vehicles from China is still limited, it won’t be long until Americans are importing Chinese vehicles made in Mexico. Subsidization rates, for example seen in BYD’s Dolphin sold at widely ranging prices in different markets, are substantial enough to dwarf the gap between USMCA duty rates and MFN rates.vii

Benchmarking ROOs impact on corporate operations

Finally, I want to offer the commission some context on ROOs for motor vehicle manufacturing operations. We should not be surprised when companies blame regulatory compliance with USMCA, among other factors, for their efforts to shift more North American manufacturing to low-wage production centers. But we also should recognize these claims ring hollow. Motor vehicle manufacturers earn more than enough to offer workers dignified pay while still enjoying healthy profits and complying with regulatory requirements. Despite last year’s UAW strike and record new contract, Big 3 automakers still made $33bn in profits and spent $14bn on share buybacks and dividend payments. This year, the Big 3 have already spent more than $7bn on share buybacks.

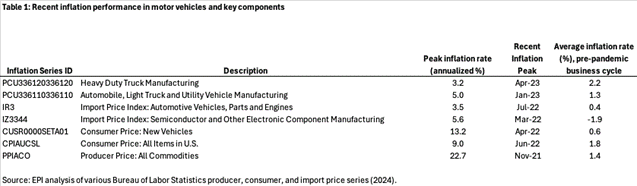

The reality of more moderate cost pressures on manufacturers can be seen in data covering the recent U.S. inflationary episode. Producer prices for light duty vehicles peaked at 5% annualized inflation and for heavy duty vehicles at 3.2% in 2023 (Table 1). Producer prices for imported semiconductors, which faced critical scarcity in the pandemic, reached an inflationary peak of 5.6% annually. Meanwhile, though, consumer prices for new vehicles reached 13.2% annualized inflation. These data points indicate that it was corporate profit-push rather than wage- or cost-pushes driving inflation. In other words, the behavior should be attributed to corporate greed rather than economic necessity.

Thank you.

Adam S. Hersh, Ph.D.

Senior Economist, Economic Policy Institute

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Table 1

Notes

i. In 2017, EPI economists outlined 6 points for NAFTA reforms: Robert E. Scott, Josh Bivens, and Samantha Sanders, Renegotiating NAFTA: What Should the Priorities Be, Economic Policy Institute Policy, December 7, 2017.

ii. International Trade Administration (ITA). 2024. Harmonized Tariff System Codes and Schedule B Codes for Trade of Motor Vehicles; Harmonized Tariff System codes, Schedule B codes, and North American Industry Classification Schedule codes for automotive parts. Accessed September 9, 2024.

iii. See for example, “Thailand-made Double Coin tires arrive in U.S.” Fleet Owner. March 30, 2018; “Linglong opens Thailand plant.” Rubber News. March 6, 2014; “Sentury Tire in Thailand: establishing a world class tire brand.” China Daily. January 21, 2016.

iv. Passenger Vehicle and Light Truck Tires from Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, and Vietnam; Invs 701-TA-647 and 731-TA-1517-1520 (Preliminary)

v. See Table 1, https://www.epi.org/publication/us-mexico-canada-agreement/

vi. “BYD weighs 3 states for electric vehicle plant.” Mexico News Daily. August 26, 2024; Machuca, Elizabeth (2024). “China’s BYD Plans Expansion Into Mexico, Rules Out U.S.” Wards Auto. May 6, 2024; Enright, Merritt (2024). “How China became the leading car supplier to Mexico and what it means for the U.S.” August 23, 2024; Mahoney, Noi (2024). “China-based automaker to invest $3B in Mexico EV plant.” April 3, 2023; “MG Motor to build manufacturing plant, R&D center in Mexico.” Reuters. August 8, 2024.

vii. Hersh, Adam. 2024. “EPI comments to the Office of the United States Trade Representative on the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement with respect to automotive goods.” January 17, 2024.