In February 2021, a year into the pandemic recession, the U.S. economy remained down 9.5 million jobs from February 2020, the last month before the economic effect of COVID-19 began. Repairing employment levels requires more than regaining those 9.5 million lost jobs; we must also consider how many jobs would have been created since February 2020. During the 12 months prior to the pandemic recession, job growth averaged 202,000 new jobs per month. Absent the COVID-19-driven recession, an estimated 2.4 million additional jobs could have been created. Adding these to the actual job losses since February 2020 implies that the U.S. labor market in February 2021 was short 11.9 million jobs (Gould 2021).

We have learned from numerous studies of the pandemic economy that these job losses are not randomly distributed across the labor market. In this year’s edition of our annual State of Working America series, we examine the current state of wages and employment in a set of reports. In our first report, we showed how low-wage workers have been the hardest hit in the recession: In 2020, 80% of job losses were among the lowest quarter of wage earners (Gould and Kandra 2021). In this report, we examine the types of jobs lost in the pandemic recession by industry, occupation, and demographic groups.

What this report finds:

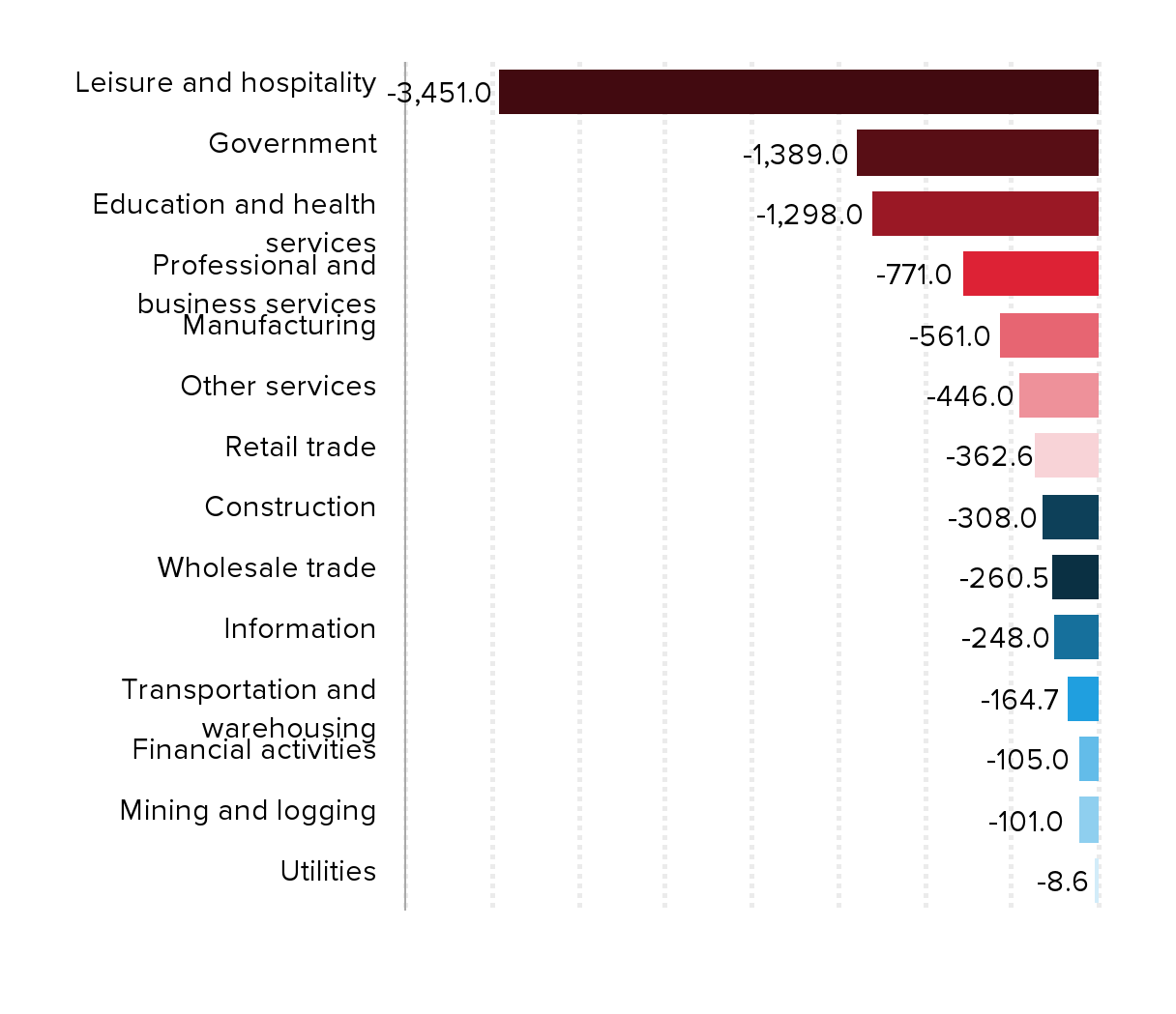

- Between February 2020 and February 2021, employment losses were largest among workers in the leisure and hospitality, government, and education and health services industries. Even with a partial bounceback last summer after losing more than 8 million jobs last spring, the leisure and hospitality sector still faces the largest shortfall, with nearly 3.5 million fewer jobs in February 2021 than a year prior.

- Within the worst-hit sectors, workers in the lowest average wage and lowest average hour occupations were hit the worst and remain most damaged a year later. While aggregate output data (for example, gross domestic product) appears to have rebounded significantly by February 2021, the “output gap”—the difference between actual and potential economic output—that remains represents a far greater share of jobs because the still-jobless workers in the economy previously worked in some of the most disadvantaged sectors in terms of wages and weekly hours.

- Within the hardest-hit sector, leisure and hospitality, Black women, Hispanic women, and Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (both men and women) saw disproportionate losses. Occupational segregation—the fact that these workers are less likely to be found in higher-paid management professions, even within leisure and hospitality—exposed them to the worst of the job losses.

- Public-sector jobs losses in the pandemic recession occurred largely within the educational services sector. Within educational services, job losses were primarily among teaching professions, although notable losses also occurred in on-site employment (e.g., food and maintenance workers, bus drivers). Higher-paid management occupations saw job gains in 2020, disproportionately accruing to men within that sector.

Job losses by sector

Figure A compares the number of jobs lost in each major sector between February 2020 and February 2021. No matter how you measure it, leisure and hospitality was the hardest hit in the pandemic downturn. After losing 8.2 million jobs during March 2020 and April 2020 combined, the leisure and hospitality sector has seen a modest bounceback, but a large shortfall in jobs remains as of February 2021. Leisure and hospitality lost nearly 3.5 million jobs—or 20.4%—since February 2020.

Government jobs—also known as public-sector employment—has the second-largest shortfall, with 1.4 million fewer jobs in February 2021 than in February 2020. The public-sector jobs shortfall is entirely in state and local governments, and most of those losses (72.0%) are in state and local government education employment. Again, these shortfalls do not account for either the number of jobs that would have been created in a growing economy had the COVID-19 recession not hit or for the growing demands the pandemic placed on education.

A deeper analysis of the two major sectors with the largest jobs shortfall—leisure and hospitality and government—is the subject of this paper.

Leisure and hospitality industry experienced great losses and continues to experience the worst shortfall: Employment change by industry (thousands), seasonally adjusted, February 2020--February 2021

| Industry | Employment change since February 2020 |

|---|---|

| Leisure and hospitality | -3451 |

| Government | -1389 |

| Education and health services | -1298 |

| Professional and business services | -771 |

| Manufacturing | -561 |

| Other services | -446 |

| Retail trade | -362.6 |

| Construction | -308 |

| Wholesale trade | -260.5 |

| Information | -248 |

| Transportation and warehousing | -164.7 |

| Financial activities | -105 |

| Mining and logging | -101 |

| Utilities | -8.6 |

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Current Employment Statistics, Establishment Survey (CES) public data series.

Leisure and hospitality

Let’s start with a look inside the private-sector leisure and hospitality industry. In the prior section and Figure A, we relied on the Current Employment Statistics (CES) from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) for job losses by major industry between February 2020 and February 2021 (BLS-CES 2021). In the remainder of the paper, we use the Economic Policy Institute’s (EPI’s) Current Population Survey (CPS) Extracts (EPI 2021) for data analysis because it allows for cross-cutting analysis by occupation, race/ethnicity, and gender. All data analysis of the CPS within this report separates the data into two time periods for maximum sample sizes in the immediate year before and during the pandemic downturn. Hereafter, “2019” refers to the 12 months from March 2019 to February 2020 and “2020” refers to the 12 months from March 2020 to February 2021. The data in the CPS are largely consistent with the CES. For example, there were 3.6 million fewer jobs in leisure and hospitality in 2020 than in 2019 using the CPS, compared to 3.5 million fewer using the CES.

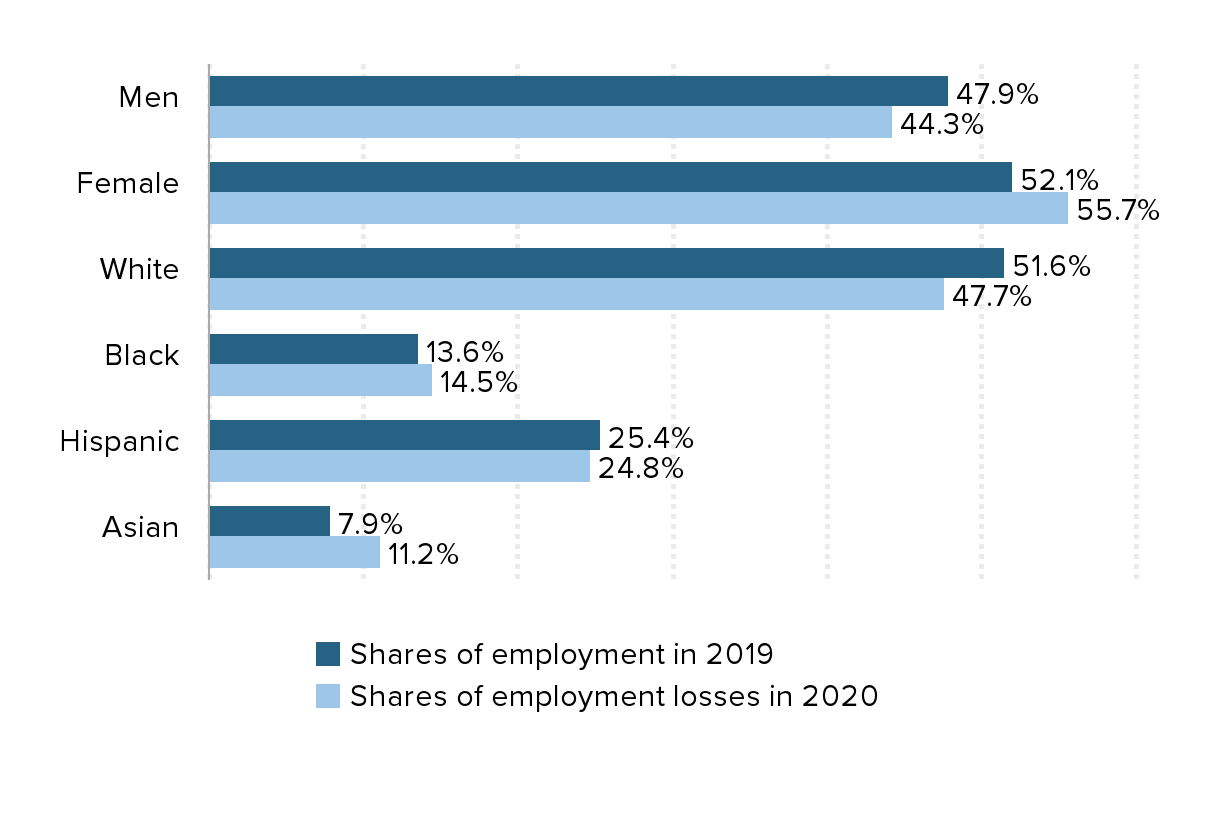

Figure B shows the broad demographics of the leisure and hospitality sector and illustrates the shares of each demographic group in that sector in the initial period (2019) and the shares of job losses in the recessionary period (2020). These comparisons allow us to see where the disproportionate losses occurred between 2019 and 2020. Women held just over half (52.1%) of the jobs in leisure and hospitality but experienced 55.7% of the job losses in this sector. Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) workers experienced the most disproportionate losses of any racial/ethnic group. While they represent 7.9% of pre-pandemic employment in leisure and hospitality, they experienced 11.2% of job losses. Black workers also saw mildly disproportionate losses compared to their pre-pandemic levels, while Hispanic workers saw proportionate losses and white workers saw fewer job losses than their proportionate shares would predict.

Women and AAPI workers experienced disproportionate losses in the leisure and hospitality sector: Employment share in 2019 and share of losses in 2020, by race/ethnicity and gender

| Shares of employment in 2019 | Shares of employment losses in 2020 | |

|---|---|---|

| Men | 47.9% | 44.3% |

| Female | 52.1% | 55.7% |

| White | 51.6% | 47.7% |

| Black | 13.6% | 14.5% |

| Hispanic | 25.4% | 24.8% |

| Asian | 7.9% | 11.2% |

Note: “2019” refers to the 12 months from March 2019 to February 2020 and “2020” refers to the 12 months from March 2020 to February 2021. Racial and ethnic categories are mutually exclusive. Hispanic refers to Hispanic/Latinx of any race while white, Black, and AAPI refers to non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic Blacks, and non-Hispanic Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders, respectively.

Source: Economic Policy. Institute Current Population Survey Extracts, Version 1.0.15 (2021), https://microdata.epi.org.

We must analyze the data in an intersectional frame to best capture differences in jobs losses among workers in different demographic groups. Figure C shows that white men suffered less-than-proportionate losses in the leisure and hospitality sector relative to their pre-pandemic employment share, while white women saw close-to-proportionate losses. Black women, Hispanic women, and AAPI workers experienced job losses in excess of their pre-pandemic labor market shares in leisure and hospitality. Both AAPI men and women saw the most disproportionate losses of any group.

Black and Hispanic women and AAPI workers experienced disproportionate losses in the leisure and hospitality sector: Employment share in 2019 and share of losses in 2020, by race/ethnicity and gender

| Shares of employment in 2019 | Shares of employment losses in 2020 | |

|---|---|---|

| White men | 24.1% | 20.1% |

| Black men | 6.4% | 6.4% |

| Hispanic men | 12.8% | 11.7% |

| Asian men | 4.0% | 5.4% |

| White women | 27.5% | 27.6% |

| Black women | 7.3% | 8.1% |

| Hispanic women | 12.6% | 13.1% |

| Asian women | 3.9% | 5.8% |

Note: “2019” refers to the 12 months from March 2019 to February 2020 and “2020” refers to the 12 months from March 2020 to February 2021. Racial and ethnic categories are mutually exclusive. Hispanic refers to Hispanic/Latinx of any race while white, Black, and AAPI refers to non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic Blacks, and non-Hispanic Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders, respectively.

Source: Economic Policy Institute Current Population Survey Extracts, Version 1.0.15 (2021), https://microdata.epi.org.

In 2019, nearly 14 million workers were employed in leisure and hospitality, or about 10% of the total workforce. Many types of jobs or occupations exist within the leisure and hospitality sector. Table 1 lists the nine major occupation categories within the leisure and hospitality sector, alongside their pre-pandemic employment level, share of industry in that occupation category in the pre-pandemic period, 2020 employment level, job losses between 2019 and 2020, and average wage and average weekly work hours in 2019.1

In the 12 months prior to March 2020, nearly two-thirds of employment in leisure and hospitality was in service occupations (64.3%), while service occupations experienced 72.3% of job losses in the pandemic recession. This is not surprising because service occupations generally require face-to-face contact and when businesses across the country shuttered, these jobs were greatly affected. A full 80% of jobs in service occupations within the leisure and hospitality sector were in food preparation and serving-related occupations in 2019.

Pandemic job losses in the leisure and hospitality industry varied widely by occupation: Job losses in major leisure and hospitality occupations between 2019 and 2020

| Occupation group | Employment (2019) | Share of industry | Employment (2020) | Job losses (level) | Job losses (shares) | Average wage (2019) | Average weekly hours (2019) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Management, business, and financial occupations | 1,704,303 | 12.9% | 1,494,902 | -209,401 | 6.0% | $28.68 | 43.1 |

| Professional and related occupations | 575,130 | 4.4% | 370,558 | -204,572 | 5.9% | $27.26 | 32.6 |

| Service occupations | 8,489,065 | 64.3% | 5,964,557 | -2,524,508 | 72.3% | $12.97 | 31.6 |

| Sales and related occupations | 1,086,265 | 8.2% | 805,046 | -281,219 | 8.1% | $13.96 | 28.1 |

| Office and administrative support occupations | 730,515 | 5.5% | 542,177 | -188,338 | 5.4% | $16.19 | 32.9 |

| Construction and extraction occupations | 39,707 | 0.3% | 25,520 | -14,187 | 0.4% | $23.35 | 37.4 |

| Installation, maintenance, and repair occupations | 103,182 | 0.8% | 82,977 | -20,205 | 0.6% | $22.77 | 37.0 |

| Production occupations | 126,698 | 1.0% | 103,221 | -23,477 | 0.7% | $16.47 | 34.5 |

| Transportation and material moving occupations | 351,779 | 2.7% | 325,949 | -25,829 | 0.7% | $13.81 | 30.7 |

Notes: “2019” refers to the 12 months from March 2019 to February 2020 and “2020” refers to the 12 months from March 2020 to February 2021. The category “farming, fishing, and forestry occupations” is omitted because it accounts for less than 0.1% of total employment.

Source: Economic Policy Institute Current Population Survey Extracts, Version 1.0.15 (2021), https://microdata.epi.org.

The second-largest occupation category within the leisure and hospitality sector is management, business, and financial occupations, with 12.9% of leisure and hospitality jobs. In 2020, this occupation category lost only 6.0% of the jobs, far fewer than would have been lost if job loss was proportionate across occupation categories. The two major occupation categories within leisure and hospitality differ in two additional ways: average hourly wages and average weekly hours.

Workers in the management occupations are the highest paid in this industry, averaging $28.68 per hour, and they have the most average weekly hours, 43.1. In comparison, service occupations have the lowest average wages in that sector ($12.97) and average only 31.6 hours per week. Combining these data to calculate average weekly wages, workers in management occupations are paid nearly three times as much as workers in service occupations. Not only was the lowest-paying industry hit the hardest by the pandemic recession, but the most vulnerable part of that sector, service occupations, received the greatest impact.

These results are consistent with the conclusions of a team of Bureau of Labor Statistics researchers who find that lower-paid workers within major industries were hardest hit and remain furthest from recovery (Dalton et al. 2021). Researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York find that lower-wage occupations have experienced the sharpest employment losses since February 2020 (Abel and Dietz 2021).

To look deeper within the leisure and hospitality sector by gender and race/ethnicity requires aggregating some of the related occupations to achieve adequate sample sizes for comparison. Service occupations have a sufficient sample size on their own. We combine the two highest-wage occupation categories—management, business, and financial occupations and professional and related occupations—into an aggregate category, management and professional occupations. We also combine two relatively low-wage and low-hour occupation categories—sales and related occupations and office and administrative support occupations—into an aggregate category, sales and office support occupations. These three occupations account for 95.3% of leisure and hospitality jobs. We drop the remaining four sectors, which together make up only 4.7% of employment in the sector overall. Table 2 presents key details of these aggregate occupational groupings.

Table 2 shows that while management and professional occupations experienced losses, these losses were far from proportionate to their share of the leisure and hospitality industry overall. Management and professional occupations also have the highest average wages and highest average weekly hours. Proportionate losses were found in sales and office support occupations, the category with the lowest average weekly hours. Disproportionately larger job losses were found in service occupations. This category represents nearly two-thirds of pre-pandemic jobs in the leisure and hospitality industry but nearly three-quarters of the job losses. Workers in this occupation category have notoriously low wages and weekly hours.

The fact that job losses were more likely to occur among low-wage and low-hour portions of the leisure and hospitality sector, a sector already fraught with low wages and low hours overall, helps explain why the output gap is smaller than the employment gap. Therefore, it is important to hold any excitement over aggregate gains, such as growth in aggregate hours or GDP, at bay (Rugaber 2021). The remaining output gap is associated with larger losses in employment, because those hurt the most in the pandemic recession work in lower-paid, lower-hour, and labor-intensive sectors (Bivens 2020).

Occupations with low average wages and hours experienced disproportionate job losses: Job losses in key leisure and hospitality occupational groupings between 2019 and 2020

| Occupation group | Employment (2019) | Share of industry | Employment (2020) | Job losses (level) | Job losses (shares) | Average wage (2019) | Average weekly hours (2019) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Management and professional occupations | 2,279,433 | 17.3% | 1,865,460 | -413,973 | 11.9% | $28.33 | 40.6 |

| Service occupations | 8,489,065 | 64.3% | 5,964,557 | -2,524,508 | 72.3% | $12.97 | 31.6 |

| Sales and office support occupations | 1,816,781 | 13.8% | 1,347,223 | -469,557 | 13.4% | $14.86 | 30.1 |

Note: “2019” refers to the 12 months from March 2019 to February 2020 and “2020” refers to the 12 months from March 2020 to February 2021.

Source: Economic Policy Institute Current Population Survey Extracts, Version 1.0.15 (2021), https://microdata.epi.org.

Aggregating five occupation groups within the leisure and hospitality sector into three groups allows us to examine pandemic job losses by certain demographic groups. Table 3 provides the baseline share of employment in 2019 for each occupation group by gender and race/ethnicity categories and then provides the share of job losses within each group for each demographic category. This allows us to better explain the job losses illustrated in Figure B and Figure C.

The losses by race/ethnicity and gender discussed above are most likely a function of occupational segregation, which is the increased probability that some workers are more likely to be found in certain jobs than other workers. We see that white men are more likely to be in higher-paid management and professional occupations than in lower-paid service or sales and office support occupations, but they have significantly less job loss than other workers. White men held about one-third of management and professional occupations within the leisure and hospitality sector but experienced only one-quarter of the job losses. In comparison, Black women, Hispanic men, and AAPI workers experienced disproportionate job losses in those jobs, even though they were less likely to be found in management and professional occupations than other occupations within the leisure and hospitality sector.

White men’s pre-pandemic employment share in service occupations was smaller than their share in management occupations, but they experienced less-than-proportionate job losses in service occupations as well. Hispanic women and AAPI men experienced disproportionate job losses in service occupations. In sales and office support occupations, Black men and AAPI workers experienced the most disproportionate losses compared with their pre-pandemic share of jobs in that occupation. Historically, AAPI workers have lower unemployment rates than white workers on average, because of their higher average levels of educational attainment, but AAPI workers in the pandemic recession appear to be facing a more difficult labor market (Kim et al. 2021). While the overall share of AAPI workers within occupations is lower than any other group within leisure and hospitality because of their lower population shares overall, we find that both male and female AAPI workers face disproportionate job losses in all leisure and hospitality occupations and, in most of these occupations, their share of job losses was more than 20% of their proportionate share of pre-pandemic jobs. Research from the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago suggests that racial bias may be a factor in the worse labor market outcomes for AAPI workers, particularly those with lower levels of educational attainment, and cannot be explained by their occupational employment patterns (Honoré and Hu 2020).

Black, Hispanic, and AAPI workers experienced disproportionate job losses compared with white workers : Employment shares in 2019 and shares of losses in 2020 in key leisure and hospitality occupational groupings, by race/ethnicity and gender

| Management and professional occupations | Service occupations | Sales and office support occupations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| White men | |||

| Share of 2019 employment | 32.5% | 22.5% | 14.3% |

| Share of losses | 25.7% | 19.4% | 15.3% |

| White women | |||

| Share of 2019 employment | 31.6% | 26.9% | 30.7% |

| Share of losses | 31.1% | 26.9% | 30.0% |

| Black men | |||

| Share of 2019 employment | 5.8% | 6.6% | 4.9% |

| Share of losses | 5.6% | 6.3% | 6.9% |

| Black women | |||

| Share of 2019 employment | 5.3% | 6.7% | 13.5% |

| Share of losses | 7.3% | 7.1% | 13.8% |

| Hispanic men | |||

| Share of 2019 employment | 9.1% | 14.5% | 8.5% |

| Share of losses | 13.2% | 12.7% | 7.6% |

| Hispanic women | |||

| Share of 2019 employment | 6.9% | 13.7% | 17.3% |

| Share of losses | 4.5% | 16.6% | 5.5% |

| AAPI men | |||

| Share of 2019 employment | 4.6% | 4.1% | 2.5% |

| Share of losses | 6.5% | 5.0% | 4.8% |

| AAPI women | |||

| Share of 2019 employment | 3.4% | 3.6% | 6.8% |

| Share of losses | 5.0% | 4.1% | 14.7% |

Notes: “2019” refers to the 12 months from March 2019 to February 2020 and “2020” refers to the 12 months from March 2020 to February 2021. The bolded numbers highlight disproportionate job losses, which is defined as 20% or more job losses than share of jobs. Hispanic refers to Hispanic/Latinx of any race while white, Black, and AAPI refers to non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic Blacks, and non-Hispanic Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders, respectively.

Source: Economic Policy Institute Current Population Survey Extracts, Version 1.0.15 (2021), https://microdata.epi.org.

Public sector

Government jobs—also known as public-sector employment—experienced the second-largest shortfall, with 1.4 million fewer jobs in February 2021 than in February 2020 (see Figure A). The public-sector jobs shortfall is entirely in state and local governments, and the vast majority of those losses (72.0%) were in state and local government education employment. We find similar results using the Current Population Survey. In 2019, the largest industrial sector within the public sector was in the educational services industry (42.3%), and the vast majority (88.6%) of public-sector losses between 2019 and 2020 were in this sector.2

Our analysis of public-sector educational services employment begins with a look inside the five major occupation categories that represent more than 98% of employment within this industry.3 Table 4 displays labor market statistics for each of these major occupation categories within the educational services sector as well as selected specific occupations within three of the major occupation categories. Of the five main occupation categories within educational services, only management, business, and financial occupations—the highest-wage occupation category within educational services—experienced employment gains between 2019 and 2020. Our analysis finds that men disproportionately benefited from these job gains. Even though men represent only 35% of employment in management, business, and financial occupations, they experienced 63% of the employment gains.

Professional and related occupations make up by far the largest occupation category within the public-sector educational services industry (71.2%). Within professional and related occupations, education instruction and library occupations has the largest share (61.5%), with K–12 teachers (preschool and kindergarten, elementary and middle school, secondary school, and special education teachers) having about two-thirds of these education instruction and library jobs. K–12 teachers also experienced the largest number of net job losses. Postsecondary teachers also experienced large losses, but these were largely offset by the increase in teaching assistants.4 Here it appears that employment losses are greatest among the higher-wage workers within education instruction (notably postsecondary teachers, but also K–12 teachers), while the gains were among the lower-wage teaching assistants. As with so many other labor market phenomena in this recession, the pandemic recession may have accelerated the already established phenomenon of shifting teaching duties away from regular faculty and onto the shoulders of lower-paid workers, such as graduate teaching assistants (McNicholas, Poydock, and Wolfe 2019). It is also possible that many of those postsecondary teachers who lost their jobs in 2020 were adjunct instructors as opposed to higher-paid full professors (Kroger 2021).

Service occupations within the public-sector educational services industry account for 9.9% of the jobs but experienced about 35% of the losses in educational services overall, second only to professional and related occupations. This is not surprising given that these service jobs require on-site employment and many schools were closed. The losses include jobs in food preparation and serving as well as building and grounds maintenance. The largest job losses within service occupations occurred in personal care and service occupations; most were from losses in child care employment, which fell by 59%. Service occupations are the lowest-paid within the public-sector education services industry.

As with service occupations, it is not surprising that transportation and material moving occupations also experienced losses while schools were closed. Although transportation and material moving occupations make up only 2.4% of public-sector educational services employment, this category had significant job losses of 25.8% between 2019 and 2020, primarily from bus drivers.

In public education, teachers lost jobs while management gained jobs: Job losses in key occupations within the public-sector educational services industry between 2019 and 2020

| Occupation group | Employment (2019) | Share of industry | Employment (2020) | Job changes | Percent change in jobs | Share of net losses | Average wages (2019) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Management, business, and financial occupations | 762,117 | 8.5% | 815,269 | 53,153 | 7.0% | N/A | $36.83 | ||

| Professional and related occupations | 6,371,282 | 71.2% | 6,086,238 | -285,044 | -4.5% | 56.6% | $30.54 | ||

| Education instruction and library occupations | 5,495,249 | 61.5% | 5,206,289 | -288,959 | -5.3% | 57.4% | $30.41 | ||

| K–12 teachers | 3,883,380 | 43.4% | 3,676,652 | -206,728 | -5.3% | 41.1% | $31.21 | ||

| Postsecondary teachers | 688,953 | 7.7% | 537,005 | -151,948 | -22.1% | 30.2% | $38.72 | ||

| Teaching assistants | 690,775 | 7.7% | 824,687 | 133,912 | 19.4% | N/A | $19.19 | ||

| Service occupations | 886,734 | 9.9% | 711,010 | -175,724 | -19.8% | 34.9% | $15.66 | ||

| Food preparation and serving related occupations | 275,705 | 3.1% | 228,747 | -46,959 | -17.0% | 9.3% | $13.55 | ||

| Building and grounds cleaning and maintenance occupations | 364,729 | 4.1% | 325,514 | -39,215 | -10.8% | 7.8% | $16.75 | ||

| Personal care and service occupations | 152,017 | 1.7% | 63,311 | -88,706 | -58.4% | 17.6% | $14.66 | ||

| Child care | 113,595 | 1.3% | 46,538 | -67,057 | -59.0% | 13.3% | $14.41 | ||

| Office and administrative support occupations | 559,256 | 6.3% | 528,422 | -30,834 | -5.5% | 6.1% | $19.77 | ||

| Transportation and material moving occupations | 212,655 | 2.4% | 157,893 | -54,762 | -25.8% | 10.9% | $18.12 | ||

| Bus drivers | 187,787 | 2.1% | 129,378 | -58,409 | -31.1% | 11.6% | $17.90 | ||

Notes: “2019” refers to the 12 months from March 2019 to February 2020 and “2020” refers to the 12 months from March 2020 to February 2021. Cells labeled N/A indicate job gains.

Source: Economic Policy Institute Current Population Survey Extracts, Version 1.0.15 (2021), https://microdata.epi.org.

As schools continue to reopen this spring, it is likely that public-sector educational services employment will experience a significant uptick. While it seems most obvious that on-site operations will need to rehire food services workers, grounds crew, and bus drivers, school systems will also need to hire more teaching professionals to help students recover from learning loss during the pandemic (García and Weiss 2020a). This need for more (not fewer) teachers is made even more difficult because the U.S. already faces a teacher shortage (García and Weiss 2020b). Fortunately, provisions in the American Rescue Plan extend much-needed relief to state and local governments as they try to retool their education systems to meet the needs of the students (Cooper, Wolfe, and Hickey 2021).

It is also worth noting that the industry with the third-largest job loss is education and health services, which has 1.3 million fewer jobs in February 2021 than in February 2020 (see Figure A). As with public-sector job losses, these private-sector jobs losses within education and health services were disproportionately found in the education portion of this sector. In 2020, education services accounted for 20.7% of jobs in this sector but 28.0% of job losses. While a thorough analysis of these industry losses is outside the scope of this report, we think it likely that private-sector education jobs are facing similar issues to public-sector education services and hopefully will rebound significantly as schools (including community colleges and four-year colleges and universities) fully reopen.

Conclusion

The pandemic recession is unusual in how focused its job losses were on low-wage workers. Lower-wage and lower-hour occupations within the leisure and hospitality sector were hit the hardest, which hurt certain demographic groups more than others. Education professions within the public sector were decimated. As public health experts deem it safe to reopen businesses and schools, employment should see a significant recovery. We will need to continue tracking the data to see whether the recovery in jobs is across the board or if certain groups continue to be left out of the recovery. Will some groups—e.g., Black or Latinx women, who are disproportionately found in certain jobs—be the last to be rehired? Or will the recovery reach them sooner? Will AAPI men and women see a rebound in line with their losses? Or will they take longer to recover? Will schools have enough resources to meet growing student needs as students return to in-person instruction? The American Rescue Plan makes important strides toward improving outcomes in coming months, but more will need to be done to make sure the most vulnerable and historically disadvantaged in our labor market realize the benefits of a growing economy and are better protected during the next disaster.

Notes

1. The farming, fishing, and forestry occupation category is removed from this chart because sample sizes were insufficient for analysis.

2. In this analysis, we have combined all levels of public-sector employment because (1) nearly all educational services employment is at the state and local levels, and (2) there is a nontrivial share of public education employment that appears to be misclassified as state when it should be local and vice versa.

3. Within educational services, the following occupation categories each represent less than 1% of employment, for a total of 1.7%: Sales and related occupations; farming, fishing, and forestry occupations; construction and extraction occupations; installation, maintenance, and repair occupations; and production occupations.

4. Even though most teaching assistants are at the local level, the gains were 96% at the state level, making up for about 90% of the postsecondary teacher losses.

References

Abel, Jaison R., and Richard Deitz. 2021. Some Workers Have Been Hit Much Harder than Others by the Pandemic. Federal Reserve Bank of New York, February 2021.

Bivens, Josh. 2020. “Curb Your Enthusiasm: Rapid Third Quarter GDP Growth Won’t Mean the Economy Has Healed.” Working Economics Blog (Economic Policy Institute), October 26, 2020.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Employment Statistics (BLS-CES). 2021. Public data series for various years accessed through the CES National Databases and through series reports. Accessed March 2021.

Cooper, David, Julia Wolfe, and Sebastian Martinez Hickey. 2021. “The American Rescue Plan Clears a Path to Recovery for State and Local Governments and the Communities They Serve.” Working Economics Blog (Economic Policy Institute), March 15, 2021.

Dalton, Michael, Jeffrey A. Groen, Mark A. Loewenstein, David S. Piccone Jr., and Anne E. Polivka. 2021. “The K-Shaped Recovery: Examining the Diverging Fortunes of Workers in the Recovery from the COVID-19 Pandemic Using Business and Household Survey Microdata.” Covid Economics, no. 71: 19–58.

Economic Policy Institute (EPI). 2021. Current Population Survey Extracts, Version 1.0.15 (2021), https://microdata.epi.org.

García, Emma, and Elaine Weiss. 2020a. “Learning During the Pandemic: What Decreased Learning Time in School Means for Student Learning.” Working Economics Blog (Economic Policy Institute), November 18, 2020.

García, Emma, and Elaine Weiss. 2020b. “Policy Solutions to Deal with the Nation’s Teacher Shortage—a Crisis Made Worse by COVID-19.” Working Economics Blog (Economic Policy Institute), October 16, 2020.

Gould, Elise. 2021. Jobs Report Shows More Than 25 Million Workers Are Directly Harmed by the COVID Labor Market: Congress Must Pass the Full $1.9 Trillion Relief Package Immediately. Economic Policy Institute (economic indicators), March 2021.

Gould, Elise, and Jori Kandra. 2021. Wages Grew in 2020 Because the Bottom Fell Out of the Low-Wage Labor Market: The State of Working America 2020 Wages Report. Economic Policy Institute, February 2021.

Honoré, Bo E., and Luojia Hu. 2020. “The Covid-19 Pandemic and Asian American Employment.” Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Working Paper, November 2020. https://doi.org/10.21033/wp-2020-19.

Kim, Andre Taeho, ChangHwan Kim, Scott E. Tuttle, and Yurong Zhang. 2021. “COVID-19 and the Decline in Asian American Employment.” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 71, no. 100563.

Kroger, John. 2021. “650,000 Colleagues Have Lost Their Jobs: A Moral Issue for Higher Education.” Inside Higher Ed. February 19, 2021.

McNicholas, Celine, Margaret Poydock, and Julia Wolfe. 2019. Graduate Student Workers’ Rights to Unionize Are Threatened by Trump Administration Proposal. Economic Policy Institute, December 2019.

Rugaber, Christopher. 2021. “Sign of Inequality: US Salaries Recover Even as Jobs Haven’t.” AP News website, February 12, 2021.