Full Report

Acronyms and initialisms

ABAWD Able-bodied adults without dependents

or documented disabilities

SNAP Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

Introduction

In recent years, Republicans in Congress have embraced proposals to ratchet up work requirements as conditions for the receipt of some federal government benefits. These proposals are clearly trying to exploit a vague, but pervasive, sense that some recipients of public support are gaming the system to get benefits that they do not need, as they could be earning money in the labor market to support themselves instead.1 Essentially, the push to increase work requirements rests on a belief that the prime barrier stopping these beneficiaries from supporting themselves solely through employment is a lack of motivation—since public benefits provide too comfortable a living, and beneficiaries lack the incentive to find paid employment.

However, a careful assessment of the current state of public benefit programs demonstrates that almost none of the alleged benefits of ratcheting up work requirements are economically significant, but that the potential costs of doing this could be large and fall on the most economically vulnerable. The most targeted programs for more stringent work requirements are the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, popularly referred to as food stamps) and Medicaid, the health insurance program for low-income people. EPI has surveyed the research literature on work requirements and how they interact with these two programs in particular, and we find that the existing safety net is too stingy and tilts too hard toward making benefits difficult to access. Tightening eligibility by increasing work requirements for these programs will make this problem even worse with no tangible benefit in the form of higher levels of employment among low-income adults.

Key findings:

- SNAP and Medicaid provide in-kind benefits for food assistance and health care to low-income families. These in-kind benefits are not generous enough to support a decent standard of living, and they provide no help with other expenses families have. In short, the incentive for adults to secure steady work at decent pay remains utterly enormous: It is the difference between living in profound material hardship versus having a more comfortable existence.

- Large numbers of beneficiaries of SNAP and Medicaid are children, retirees, or people with disabilities that prevent them from working. While most variants of work requirements seem to only apply to able-bodied adults without dependents or documented disabilities (ABAWDs), the administrative burden associated with these requirements might spill over and reduce take-up (and hence, incomes) for other beneficiaries.

- The primary barrier to work for low-income adults who want steady hours of employment is the state of the macroeconomy—conditions that are far beyond their control. The history of work requirements often casts them as an effort to break a “culture” of nonwork among some communities, with the implicit argument being that many beneficiaries will choose not to work even when steady jobs with decent pay are readily available. The evidence strongly contests this: Low-income adults’ employment surges when overall unemployment is low, and they work more hours and are able to earn more as a result. When unemployment is high, however, low-income adults are often the first to lose their jobs and see large hour declines as well.

- Too many jobs available to adults in low-income families are often characterized by irregular and unpredictable scheduling practices, making it hard for workers to plan for and maintain consistent work.

- More stringent work requirements implemented in the past have largely failed to boost work in significant ways because these requirements do not attack the core problems of weak macroeconomic conditions, the volatile nature of low-wage work, and other barriers to work like caregiving responsibilities.

- Many of the programs that some people might be excluded from by work requirements can meaningfully be thought of as work supports. Some public benefit programs—particularly Medicaid and SNAP—serve as human capital investments that can boost long-run earnings and employment prospects.

In the end, we suspect much public support for enhanced work requirements reflects imprecise thinking about the true costs and benefits of implementing them in the messy world of low-wage work in the United States. Other support might stem from the ethical decision that it’s worse for society to have even a tiny number of “undeserving” people receive public support than it is to have thousands of deserving families shut out of needed benefits because of the onerous administrative burden associated with tightened work requirements. But this is not an ethical decision we share. We think a decent, compassionate welfare state should err on the side of protectiveness rather than exclusion—but this trade-off is the hinge of political decisions around ratcheting up administrative reporting on work requirements.

What are work requirements, and what problem are they supposed to solve?

Work requirements are policies that mandate individuals work and administratively document a certain number of hours as a condition to receive benefits like SNAP and Medicaid. At a broad level, work requirements don’t seem to belong with welfare-state programs like SNAP and Medicaid. These programs were historically established precisely to provide a floor to living standards for people who cannot support themselves through earnings from the labor market. This includes children, the elderly, students, adults with disabilities or primary caregiving responsibilities, or those seeking work who cannot find it.

The implicit claim made by many advocating for strict work requirements on public support programs is that benefits have become too easy to obtain (even for those who could find paid work) and too generous relative to labor market earnings. The claim continues that this excess generosity has incentivized a portion of the population to game the system by choosing to live on public benefits rather than work. The argument, hence, claims that by making it harder for this group to obtain benefits, their incentive to work will be increased, and this will raise employment rates. In practice, existing work requirements are mainly aimed at adults without dependents or documented disabilities—a group that proponents of work requirements think could be working if only the public support systems were not so generous relative to paid employment.

Before moving on to the flawed assumptions this view makes about the population that work requirements apply to, it is worth noting that there is almost no cash assistance that is unconditional on work and available to that population. Most current policy debates about work requirements center on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and Medicaid. These programs provide in-kind benefits to purchase food and health insurance to cover medical bills if one needs health care. In short, there is no prospect at all of somebody achieving a remotely comfortable living standard by forgoing work and relying exclusively on the benefits provided by these programs. People need much more than food and health care to live a decent life.

Besides the logical flaw that millions of Americans are voluntarily choosing to not work because public benefits offer such a comfortable alternative, the advocacy of tighter work requirements often makes several flawed assumptions about the labor market trade-offs that individuals affected by work requirements face (often referred to as ABAWDs, short for able-bodied adults without dependents or documented disabilities). Supporters of stricter work requirements assume that existing social safety net benefits are easy to access and provide a generous-enough living standard to be a reasonable substitute for steady work. In addition, these supporters assume that good-paying, steady jobs are readily available and a viable alternative to living on public benefits. This is often false. Our analysis shows that low-wage labor markets in the United States do not readily provide enough hours or wage and salary income high enough to guarantee a minimally decent life for workers. Further, it assumes that ABAWDs have no other health issues or caregiving responsibilities that would prevent them from finding steady work.

This view doesn’t square with reality, both with respect to the trade-offs low-income families face between work and nonwork and the labor market experiences of people who would be affected by work requirements (many of whom already seek work regularly and take it when it’s available). In this report, we document the economic claims (some implicit, some explicit) made by policymakers who support taking away benefits from individuals who fail to meet work reporting requirements, and we show why these claims don’t reflect the reality of low-wage labor markets and the poor and near-poor families who must try to carve out a living from them. We further document the evidence of the impacts of work requirements on individuals and communities. The evidence shows the real harms work requirements can cause and suggests that ratcheting up their stringency would greatly amplify these harms.

Adults without dependents or documented disabilities are most likely to be targeted for work requirements

Today’s work requirements generally target non-elderly adults without documented disabilities who do not have dependents living in the home, a group that work-requirement advocates claim should be able to find steady and income-sustaining work. These ABAWDs make up one-third of the U.S. population (Bauer, Hardy, and Howard 2024). ABAWDs that have incomes less than 200% of the federal poverty line (FPL) are 8.2% of the total population, which would put them in income ranges to be eligible for social safety net programs like SNAP and Medicaid (Bauer, Hardy, and Howard 2024). Table 1 compares the demographic and safety net profile of all adults ages 18 to 59, adults who are SNAP and Medicaid users, and low-income ABAWDs. Compared with all adults, those receiving SNAP and Medicaid are disproportionately likely to be women and nonwhite. They are also less likely to have a college education—only 15% of adults on SNAP and Medicaid have a bachelor’s degree or higher. Finally, adults on SNAP and Medicaid are much more likely to have an elderly person in the household. This population looks very similar to the ABAWD population, in which nearly 50% of low-income ABAWDs are women, and a disproportionate share are Black and Hispanic (18% and 23%, respectively), relative to all adults. More than half of low-income ABAWDs have a high school diploma or less.

Demographic composition of adults ages 18–59, adults who use SNAP or Medicaid, and low-income adults without dependents or receiving income from disability

| All | SNAP or Medicaid users | Low-income without dependents or receiving income from disability | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 38.1 | 36.7 | 37.5 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 50.1% | 46.4% | 52.0% |

| Female | 49.9% | 53.6% | 48.0% |

| Race | |||

| White | 56.3% | 42.9% | 50.1% |

| Black | 13.6% | 19.8% | 18.1% |

| Hispanic | 20.7% | 29.0% | 23.6% |

| Other | 9.4% | 8.3% | 8.2% |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 9.1% | 17.7% | 14.9% |

| High school | 27.6% | 39.4% | 37.1% |

| Some college | 26.7% | 28.0% | 28.3% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 23.7% | 11.2% | 14.9% |

| Advanced degree’ | 13.0% | 3.6% | 4.8% |

| Has an elderly person in household | 9.8% | 14.3% | 13.8% |

| Has a disability that hinders or limits work | 7.2% | 18.0% | 20.7% |

| Has SNAP | 11.2% | 52.3% | 24.8% |

| Has Medicaid | 16.1% | 75.3% | 31.9% |

| Has EITC | 8.4% | 20.4% | 15.3% |

| Number of hours worked in a year | 1,527 | 1,000 | 768 |

| Average income from work | $50,997 | $19,102 | $8,745 |

Note: Workers receiving income from disability includes income from workers’ compensation, company or union disability, federal government civil service disability, U.S. military retirement disability, state or local government employee disability, U.S. Railroad Retirement disability, accident or disability insurance, black lung miner’s disability, or state temporary sickness payments. Income from Social Security and payments from the Veterans Administration were not included.

Source: Author’s analysis of Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC).

While ABAWDs might not have documented disabilities that result in benefit receipt or have dependent children living at home full-time, they often experience health challenges and must take on some caregiving duties, each of which could provide a genuine barrier to finding steady work. We find that 21% reported having a disability that affects their ability to find and sustain work, suggesting that adults with genuine health barriers are being swept up in overly stringent work requirements. One potential outcome from a push to ratchet up work requirements for adults with disabilities is increased time spent doing administrative paperwork to more precisely define their health challenges.

Table 1 also shows that 13.8% of ABAWDs live with an adult over the age of 65 in their household, suggesting that many are potential caregivers in some form and likely have caregiving responsibilities beyond what is captured on paper. A recent Brookings Institution report corroborates this finding, showing that nearly 40% of low-income ABAWDs are parents, and 5% are noncustodial parents to children under the age of 21 (Bauer, Hardy, and Howard 2024). While most variants of work requirements seem to only apply to ABAWDs and not all SNAP and Medicaid beneficiaries, given how similar the overall populations are, and the fact that many SNAP and Medicaid adult users often have children, the administrative burden associated with these requirements might spill over beyond ABAWDs alone and reduce take-up (and hence incomes) for these other beneficiaries. Adding more work requirements will create confusion and more paperwork for all adults who receive SNAP and Medicaid, not just ABAWDs, the group most likely to have work requirements levied on them.

The social safety net offers minimal support to low-income ABAWDs

Despite ABAWDs having health challenges and caregiving responsibilities that make participation in the labor market difficult, our current social safety net does very little to support these adults. ABAWDs receive a very small share of in-kind income from benefits, and these benefits come with strings attached. In the case of food assistance through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, ABAWDs who are not homeless or veterans must work 80 hours per month to receive SNAP benefits or lose these benefits if they don’t meet the hours-worked criteria for three months in a row (USDA 2024). In the case of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), adults without dependents receive an average annual benefit of $295, one-tenth of what families with children get (Crandall-Hollick, Falk, and Boyle 2023).

To get a sense for how much support ABAWDs receive from the government, researchers compared the poverty rate of ABAWDs with comparable adults with children before and after social safety net transfers (Gornick et al. 2024). Between 2016 and 2019, the pre-tax, pre-transfer poverty rate for nondisabled childless adults was 12.7%, and after taxes and transfers, the poverty rate for this group was only 2.4 percentage points lower (10.3%). By contrast, for nondisabled adults with children, social assistance programs reduced the incidence of poverty for this group by 5.4 percentage points—more than twice as much as that of childless adults. This lack of social safety net support for nondisabled, childless adults is unique to the U.S. Further, the U.S. ranked last in its ability to reduce poverty for nondisabled, childless adults—reducing poverty for this group by only 19% compared with 35%–66% for Canada, the UK, the Czech Republic, Finland, Ireland, and the Netherlands (Gornick et al. 2024).

With very few safety net programs to support them otherwise, ABAWDs are hence already heavily incentivized to work, so tighter work requirements are not needed to further this incentive. Under the status quo, living standards for ABAWDs are far higher if they are able to find steady, sustaining work.

Low-income adults generally face steep labor market challenges, making it difficult to meet work requirements

With such meager government support, adults without dependents or documented disabilities are clearly motivated to turn toward employment and to work more when possible. Moreover, just because adults with children are so far exempt from some work-requirement proposals, they, too, would benefit from increased employment. If advocates of work requirements were motivated to boost living standards for low-income households through policy, then efforts to boost employment opportunities across all low-income households, not just ABAWDs, would make sense.

The first clear labor market challenge for ABAWDs is one shared by low-income families with children and even by more privileged job seekers—the United States has spent far too much time with excess unemployment rates in recent decades. This excess unemployment rate represents a clear and profound macroeconomic policy failure: the failure to maintain economywide spending at levels that would ensure that employer demand for workers was strong enough to soak up all willing workers in a reasonable amount of time (Bivens and Zipperer 2018). This macroeconomic failure is something no individual worker has control over, yet it is entirely determinative of whether all (or even the vast majority of) potential workers are able to find regular work at sustaining wages.

Advocates for more stringent work requirements gloss over this reality of the labor market. They portray the population affected by work requirements as stubbornly refusing to move into paid employment when it is available—often claiming they are afflicted by a “culture” of nonwork. But when unemployment is high, steady work is often unavailable. Employment rates for low-income adults without dependents (just like work for all adults) is highly cyclical, rising when the macroeconomic environment is more favorable and overall unemployment rates fall, and falling when overall unemployment rises due to slack job markets.

Figure A shows the number of hours worked for adults in the bottom 30th percentile of the household income distribution between 1979 and 2019. As unemployment increases, the number of available jobs in a given local labor market becomes scarce, and workers work fewer hours, suggesting that the jobs low-income adults take are much more tied to aggregate labor market health. Given that more than 80% of workers in this group lack a college degree, these adults are much more likely to work in sectors that don’t require higher levels of education, such as construction or the restaurant industry, which are highly cyclical in nature.

Higher unemployment is associated with fewer work hours for low-income adults: Total hours worked and unemployment rate for the bottom 30% of households, 1979–2019

| year | Unemployment rate (%) | Hours worked |

|---|---|---|

| 1979 | 4.95 | 1235.1 |

| 1980 | 6.29 | 1213.1 |

| 1981 | 6.84 | 1193.7 |

| 1982 | 8.98 | 1150.7 |

| 1983 | 8.92 | 1167.3 |

| 1984 | 6.86 | 1229.6 |

| 1985 | 6.61 | 1266.9 |

| 1986 | 6.45 | 1285.2 |

| 1987 | 5.69 | 1308.5 |

| 1988 | 5.03 | 1320.2 |

| 1989 | 4.88 | 1365.5 |

| 1990 | 5.22 | 1361.2 |

| 1991 | 6.46 | 1334.1 |

| 1992 | 7.20 | 1328.4 |

| 1993 | 6.65 | 1352.2 |

| 1994 | 5.89 | 1361.0 |

| 1995 | 5.43 | 1374.9 |

| 1996 | 5.27 | 1375.0 |

| 1997 | 4.82 | 1382.2 |

| 1998 | 4.46 | 1400.1 |

| 1999 | 4.20 | 1409.0 |

| 2000 | 4.04 | 1400.6 |

| 2001 | 4.78 | 1356.1 |

| 2002 | 5.93 | 1322.7 |

| 2003 | 6.17 | 1307.4 |

| 2004 | 5.71 | 1311.8 |

| 2005 | 5.35 | 1317.9 |

| 2006 | 4.90 | 1349.3 |

| 2007 | 4.94 | 1339.4 |

| 2008 | 6.18 | 1277.9 |

| 2009 | 9.72 | 1177.1 |

| 2010 | 10.07 | 1144.2 |

| 2011 | 9.41 | 1147.4 |

| 2012 | 8.65 | 1173.2 |

| 2013 | 7.99 | 1199.0 |

| 2014 | 6.84 | 1215.9 |

| 2015 | 5.98 | 1255.2 |

| 2016 | 5.62 | 1279.4 |

| 2017 | 5.16 | 1289.9 |

| 2018 | 4.71 | 1319.2 |

| 2019 | 4.55 | 1361.0 |

Note: The relationship between unemployment rate and hours worked displayed in the figure are adjusted for a time trend. We define the bottom 30% of households based on their total income from wages and salaries.

Source: Author’s analysis of Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC) (Flood et al. 2024).

Figure B shows a similar pattern for household income from wages. When unemployment is low, income for low-income adults increases, presumably because jobs are less scarce, and workers are able to work more hours. However, as unemployment increases, household income from work declines.

Higher unemployment is associated with lower income for low-income adults: Total household labor income and unemployment rate for the bottom 30% of households, 1979–2019

| year | Unemployment rate (%) | Household income ($) |

|---|---|---|

| 1979 | 4.95 | $37,696 |

| 1980 | 6.29 | $34,989 |

| 1981 | 6.84 | $33,302 |

| 1982 | 8.98 | $32,539 |

| 1983 | 8.92 | $32,628 |

| 1984 | 6.86 | $33,217 |

| 1985 | 6.61 | $34,396 |

| 1986 | 6.45 | $36,259 |

| 1987 | 5.69 | $35,847 |

| 1988 | 5.03 | $36,370 |

| 1989 | 4.88 | $37,437 |

| 1990 | 5.22 | $36,583 |

| 1991 | 6.46 | $35,693 |

| 1992 | 7.20 | $35,177 |

| 1993 | 6.65 | $35,543 |

| 1994 | 5.89 | $36,223 |

| 1995 | 5.43 | $37,479 |

| 1996 | 5.27 | $37,656 |

| 1997 | 4.82 | $37,217 |

| 1998 | 4.46 | $38,491 |

| 1999 | 4.20 | $39,085 |

| 2000 | 4.04 | $39,169 |

| 2001 | 4.78 | $38,418 |

| 2002 | 5.93 | $37,216 |

| 2003 | 6.17 | $36,546 |

| 2004 | 5.71 | $35,618 |

| 2005 | 5.35 | $35,664 |

| 2006 | 4.90 | $36,583 |

| 2007 | 4.94 | $36,461 |

| 2008 | 6.18 | $34,449 |

| 2009 | 9.72 | $32,866 |

| 2010 | 10.07 | $31,127 |

| 2011 | 9.41 | $30,592 |

| 2012 | 8.65 | $30,629 |

| 2013 | 7.99 | $32,451 |

| 2014 | 6.84 | $32,230 |

| 2015 | 5.98 | $34,555 |

| 2016 | 5.62 | $36,317 |

| 2017 | 5.16 | $36,910 |

| 2018 | 4.71 | $38,090 |

| 2019 | 4.55 | $41,208 |

Note: The relationship between unemployment rate and labor income displayed in the figure are adjusted for a time trend. We define the bottom 30% of households based on their total income from wages and salaries.

Source: Author’s analysis of Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC) (Flood et al. 2024).

By making the incentives faced by ABAWDs the central policy concern that motivates work requirements, rather than the larger macroeconomic environment, advocates for work requirements are not being honest about the real barriers to work.

Low-wage work is precarious, making work time hard to maintain

In addition to work availability being tied to labor market health for low-income ABAWDs, the types of jobs available to this group even in times of general economic health often pay low wages and are precarious in nature. It is difficult for workers to maintain a consistent number of work hours each month when they are scheduled for many hours one week and a few hours the next week, or when their employee classifications shift from full-time, full-year employment to part-time, temporary, and contractor work arrangements (Farber 2008; Kalleberg 2009, 2011, 2012; Kalleberg and Marsden 2013). These employment arrangements and scheduling practices, which are often out of workers’ control, decrease the regularity and predictability of work time and can make it hard for workers to maintain the consistent work-hour requirements needed to satisfy the documentation (by either working 80 hours per month or 20 hours per week). For example, workers with seasonal jobs would only be eligible for benefits during the season that they work but would be unable to access benefits at crucial moments when they’re laid off, even if they have reasonable assurance that they will be reemployed or they are actively seeking employment. Moreover, a disproportionately large share of workers in low-wage jobs (66% of janitors and housekeepers, 90% of food service workers, 87% of retail workers, and 71% of home care workers) reported their hours varied within the last month, which highlights the pervasiveness of such practices (Lambert, Fugiel, and Henly 2014).

Figure C shows the rate at which workers report having variable hours, conditional on working, for workers in the bottom 30% of household labor income and workers in the upper 70%. Workers in low-income households have substantially higher rates of hour variability, with the gap widening during economic downturns and narrowing during periods of labor market health. Critically, research has shown that the rise in hour variability often goes hand in hand with low numbers of work hours, where workers with low income both work the fewest hours during downturns and have the most variable hours (Cai 2023).

Workers in low-income households experience more hour variability than those in higher income households: Share of workers that report their hours vary, conditional on being employed, 2000–2023

| Year | Upper 70% | Bottom 30% |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 6.0% | 11.6% |

| 2001 | 6.2% | 12.4% |

| 2002 | 6.2% | 12.0% |

| 2003 | 6.6% | 13.0% |

| 2004 | 6.8% | 13.4% |

| 2005 | 7.0% | 13.4% |

| 2006 | 6.5% | 12.6% |

| 2007 | 6.1% | 11.7% |

| 2008 | 6.0% | 11.9% |

| 2009 | 6.0% | 13.2% |

| 2010 | 5.9% | 13.3% |

| 2011 | 5.7% | 12.7% |

| 2012 | 6.0% | 13.0% |

| 2013 | 5.7% | 12.3% |

| 2014 | 5.4% | 11.4% |

| 2015 | 5.3% | 10.7% |

| 2016 | 5.0% | 10.2% |

| 2017 | 4.8% | 9.7% |

| 2018 | 4.5% | 9.5% |

| 2019 | 4.7% | 9.1% |

| 2020 | 4.3% | 9.4% |

| 2021 | 4.3% | 9.8% |

| 2022 | 4.1% | 8.6% |

| 2023 | 3.9% | 8.1% |

Notes: We define the bottom 30% of households based on their total income from wages and salaries.

Source: Author’s analysis of EPI CPS Outgoing Rotation Group microdata extracts, Version 1.0.59 (EPI 2024).

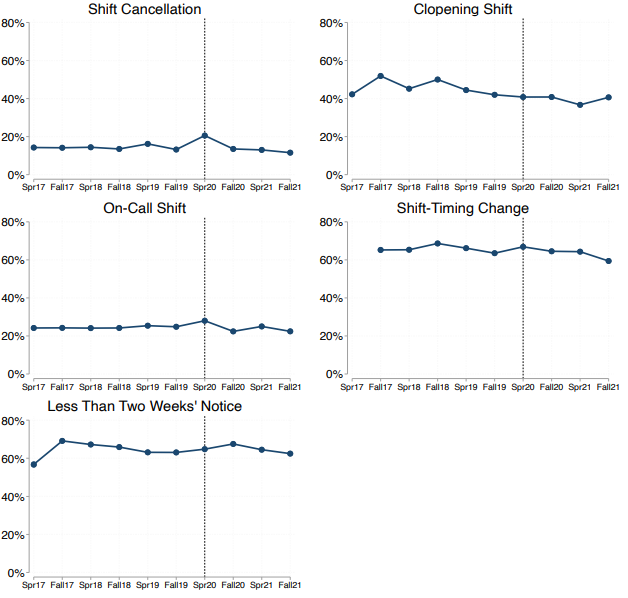

Hour variability is just one type of scheduling practice that might make it hard for workers to document working a consistent 20 hours per week to fulfill work requirements. Figure D below, reproduced from the Shift Project, highlights the pervasiveness of scheduling practices that make it challenging to rely on a job to provide steady income over time (Zundl et al. 2022). These practices include employers canceling shifts, changing shift times, and giving less than two weeks’ notice for a work schedule to employees. While these trends are just for the service sector, this is an important industry to understand in the context of work requirements since many of the workers in the service sector earn low wages and are eligible for SNAP and Medicaid.

In 2021, around 15% of workers reported having their shifts canceled, and nearly 40% of workers reported working a so-called “clopening” shift (a scheduling practice where managers schedule the same worker to work a closing shift followed by an opening shift the following day). Just over one-third of the service sector reported being scheduled for an on-call shift, and around 60% of workers reported a shift-timing change or were given less than two weeks’ notice of a schedule change (Zundl et al. 2022). Critically, the graphs further show how these conditions persist even in favorable macroeconomic conditions.

Retail and service-sector workers experience substantial scheduling instability: Scheduling experiences from workers in retail and service sectors

Source: Replication of Figure 1 from the Shift Project Research Brief (Zundl et al. 2022).

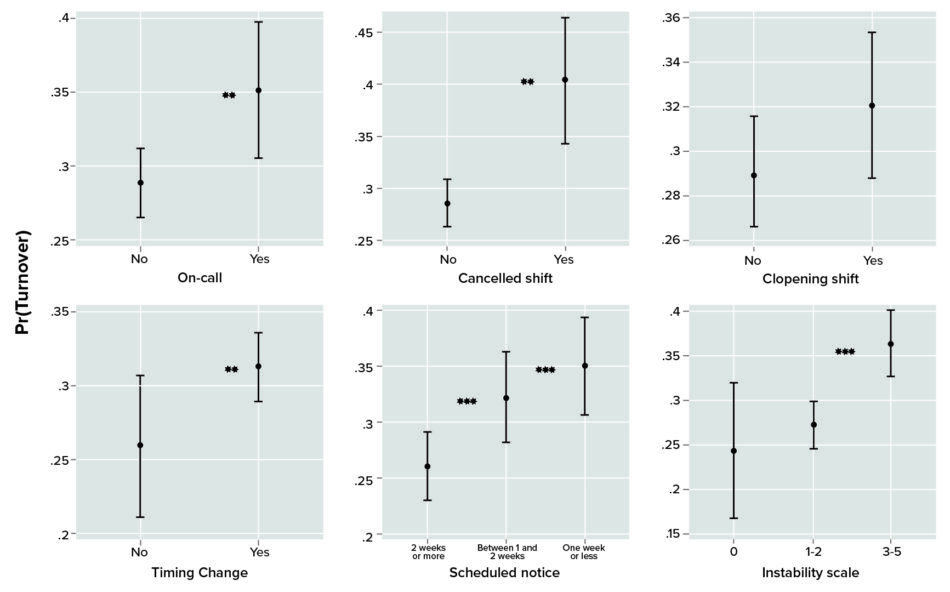

These scheduling practices have implications for workers’ ability to have consistently predictable schedules and can have spillover impacts on their ability to hold down jobs altogether. Late notice or on-call shifts, for example, can make it very hard to plan for caregiving duties, and if workers need to use public transit, last-minute notice may cause them to be late or miss their shifts if they can’t catch the right bus. Unsurprisingly, job turnover is high in jobs with these scheduling practices. Figure E shows that workers who have to work on-call shifts have around a 7 percentage point higher rate of job turnover than workers who do not. Similarly, workers who experience scheduling time changes have a higher rate of turnover than workers who do not have employers that change schedules at the last minute. Workers with little schedule notice and workers who experience canceled shifts, similarly, are more likely to experience job turnover than workers with more notice (Choper, Schneider, and Harknett 2021).

Workers with greater scheduling instability are more likely to experience job turnover: Predicted probability by types of schedule instability

Source: Replication of Figure 1 from “Uncertain Time: Precarious Schedules and Job Turnover in the US Service Sector” (Choper, Schneider, and Harknett 2021).

Taken together, the available labor market options for ABAWDs present often-overlooked challenges to maintaining steady work. Work is only available under the right macroeconomic conditions, and even then, the conditions of work can prevent workers from maintaining steady hours or employment. The high levels of turnover that occur from workers seeking better work conditions make it nearly impossible to maintain eligibility for income assistance if recipients are required to demonstrate consistent work.

A Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) report corroborates this by showing that half of low-income workers who were subject to Medicaid work requirements would have failed a work-hours test in at least one month over the course of the year (Katch, Wagner, and Aron-Dine 2018). Note, though, that this means that those workers would likely have passed the work-hours test in the eleven other months. Moreover, in occupations in which SNAP or Medicaid beneficiaries are concentrated, unemployment is twice as high as the unemployment rate for typical middle-class occupations (Butcher and Schanzenbach, 2018). Penalizing workers for job conditions beyond their control is yet another way that advocates for work requirements are not being honest about the real intent of work requirements.

Work requirements don’t actually boost employment

The stated goal of work requirements is often to increase work effort, often to 80 hours per month or 20 hours per week for ABAWDs. But the prior section showed that the jobs available to low-income workers generally are not good-quality jobs with dependable hours that enable workers to meet the thresholds to maintain benefits. Moreover, ABAWDs cannot rely on the social safety net for economic security, suggesting that the argument—that changing ABAWDs’ incentives (via work requirements) will bring more people into the workforce and off social safety net programs—is flawed. This flaw is confirmed in academic research: Where work requirements exist, there has been no meaningful increase in employment.

In the past, there have been empirical challenges in causal analysis estimating the impact of work requirements on employment. Described in Gray et al. (2023), participation in programs like SNAP is underreported in most major surveys, making it difficult to gauge any change in participation in response to policy (Meyer, Mittag, and George 2020; Ziliak 2015; Meyer and Mittag 2019). Additionally, not all adults who are eligible for programs like SNAP actually take up the programs, and these underlying preferences driving the take-up decision are unknown to researchers. As a result, estimates of employment based on a policy change on this population might be smaller in magnitude than they would be if we could simply capture adults who were eligible for SNAP and had a preference for using it. Finally, there may be selection bias if researchers limit the study sample to those most likely to be impacted by work requirements. In the context of SNAP, Gray et al. (2023) overcame empirical challenges by using linked administrative data to causally assess the impact of work requirements when they were reinstated after the Great Recession and found that the work requirements had no impact on employment. Others have similarly found no impact of work requirements on employment (Vericker et al. 2023; Stacy, Scherpf, and Jo 2018; Feng 2022; Cook and East 2024).

Studies of the effects of work requirements on Medicaid have yielded similar results. Two phone surveys in Arkansas following the 2017 introduction of work requirements to Medicaid found no discernible change in employment, in part because an estimated 38%–48% of recipients newly subject to work requirements were already working at least 20 hours per week (Sommers et al. 2020). This finding is totally consistent with our general argument here: Low-income adults already have a huge incentive to work but face high external barriers, aside from any internal barrier that might exist such as a lack of motivation. Given this, there is little reason to think that work requirements would meaningfully boost employment.2

By making the process of applying for crucial safety net programs more burdensome, work requirements effectively function like a cut to programs

While work requirements do not reliably increase employment, they do significantly increase the administrative burden and costs of applying for safety net programs. This increased administrative burden, in turn, reduces access and take-up. Prior studies have shown that administrative burdens of all kinds can reduce program enrollment (Cook and East 2024; Deshpande and Li 2019; Finkelstein and Notowidigdo 2019; Gray 2019; Homonoff and Somerville 2021), and increases in work requirements are no exception.

For adults trying to ascertain if they’re eligible for safety net programs, policies that increase work requirements will lead to increased learning and compliance costs associated with gaining access to these programs (Herd and Moynihan 2018). For example, when new work requirements go into place, adults with limited literacy or who face language barriers may not know about these requirements and lose coverage as a result. Workers may also face hurdles in getting employers to provide enough hours to meet the work requirements and the additional paperwork to verify employment hours per week (Bauer and East 2023).

While some of the reductions in caseloads due to work requirements may truly be because workers can’t satisfy the arbitrary hours threshold, in many cases, the sheer amount of additional administrative burdens levied on adults seeking benefits, and on case workers screening to ensure that work requirements are met, is a major driver in the decline in participation. In the same rigorous academic studies that found minimal employment impacts in response to work requirements for SNAP, researchers found that the new work requirements increased program exits by 64% among incumbent participants, and for participants newly subject to work requirements, program participation was reduced by 53% (Gray et al. 2023). In response to Medicaid’s work requirements in Arkansas, researchers documented a decline in Medicaid coverage by 13.2 percentage points, while the share of the uninsured increased by 7.1 percentage points (Sommers et al. 2019).

The consequences of losing access to SNAP and Medicaid for low-income adults are severe, often resulting in food and health insecurity. Losing SNAP eligibility has been found to increase the incidence of experiencing physically unhealthy days by 14% (Feng 2022). Following the Medicaid work requirements experiment in Arkansas, researchers compared outcomes for respondents who were still enrolled and respondents who were disenrolled from the program. Among those disenrolled, 49.8% reported serious problems paying off medical debt, almost twice as many respondents compared with 26.8% for those still enrolled. Moreover, 55.9% of disenrolled respondents delayed needed care in the past year because of cost, and 63.8% delayed taking medications because of cost. By contrast, only 28.2% of enrolled respondents delayed needing care, and 32.8% delayed medications (Sommers et al. 2020).

The silver lining in these findings is that when administrative burdens are reduced, people regain access to crucial benefits. For example, during the 2008–2009 Great Recession, policymakers significantly (if temporarily) reduced requirements for SNAP receipt. These changes were made because it was recognized that the recession—a change in macroeconomic conditions outside the control of potential beneficiaries—was driving the increased need for SNAP. Researchers found that these administrative policies that relaxed requirements explained 28.5% of the 69% increase in SNAP participation (Ziliak 2013). Research has further shown that participation is greatest when measures to reduce the administrative burden for SNAP—like lengthening eligibility and recertification periods, eliminating in-person interviews, and offering online applications—are more generous (Herd and Moynihan 2018; Prenatal-to-3 Policy 2024).

Policies that would measurably improve employment in low-income households

For those genuinely concerned about improving access to work, there are policy choices that are far more effective than work requirements.

This agenda would include macroeconomic policy to maintain full employment but would also stress policy choices that remove real-world barriers to work like providing access to child and elder care, reducing incarceration, enforcing antidiscrimination laws, and removing unnecessary credentialization in the hiring process.

Maintaining full employment: Our analysis in prior sections shows a clear link between hours worked and earnings for low-income adults and the national unemployment rate, suggesting that when the economy is at full employment, low-income adults stand to benefit the most from greater access to work opportunities. It is also worth noting that full employment also leads to strong reductions in the federal budget deficit—something else proponents of work requirements also claim is a goal (Bivens 2019).

Increasing scheduling predictability: Adding hours criteria to individuals in jobs with schedule practices that are out of their control only increases both barriers to work and economic insufficiency. If policymakers were serious about supporting individuals who want steady work, they would call for workplace protections that reduce precarious scheduling practices, thereby providing more employment security. Policies like secure scheduling laws can go far to improve employment prospects for low-income ABAWDs. Studies of new secure scheduling laws, which mandate that workers get at least two weeks’ notice of their schedule, among other rules, found that these policies increase economic security and worker health and well-being (Harknett, Schneider, and Irwin 2021).

Providing better help with caregiving responsibilities: For adults with caregiving duties, a key barrier to work is the prohibitively high cost of care. Given that 5% of ABAWDs have noncustodial children under 21 and 14% of ABAWDs live with a person over the age of 65, access to affordable child and elder care could make a huge difference for this population of adults. Women charged with caregiving have lower employment and earnings than those with similar characteristics who are not caregivers (Maestas, Messel, and Truskinovsky 2024). Policies that could support caregivers or reduce the cost of elder care could significantly help ABAWDs gain access to employment. For example, studies show that when barriers to child care are reduced through informal or formal care, women are much more likely to work (Posadas and Vidal-Fernandez 2013; ASPE 2016).

Reducing the labor market scarring of incarceration: For Black men, incarceration presents a uniquely challenging obstacle in terms of gaining employment (Pager 2003; Williams, Wilson, and Bergeson 2019). At least one in five Black men will experience incarceration at some point in their lives (Robey, Massoglia, and Light 2023), and any instance of incarceration severely reduces their subsequent likelihood of gaining employment (Pager 2003). Policies that reduce incarceration and recidivism rates, such as job reentry programs, could do much more to support this population’s gaining employment.

Reducing misplaced credentialization: Degree inflation—the rising demand for a four-year college degree for jobs that previously did not require one—has been found to be costly to workers in terms of missed job opportunities (Cohen 2023). A Harvard Business Review study found that over 60% of employers indicated that they would reject candidates that otherwise fit their job descriptions because they did not have college diplomas (Fuller and Raman 2017). Given that a large share of ABAWDs lacks college degrees, this can hinder their ability to gain access to employment they might be fully qualified for otherwise. Moreover, degree inflation appears to be responsive to local labor market supply. When there is an economic downturn and an increased number of people looking for work, employers are more likely to increase skill requirements (Modestino, Shoag, and Ballance 2020). By contrast, when the economy is tight, employers tend to relax them (Modestino, Shoag, and Ballance 2016). This suggests that the degree requirement, rather than being a necessary qualification for a job, serves as an unfair screening device that may actually hurt employers in the long run.

Reducing education requirements has been a bipartisan policy initiative in Alaska, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Utah, where governors eliminated the requirement of a four-year college degree for many jobs in state government. Research has also shown that when degree requirements are dropped, employers are more specific in their job descriptions about the types of skills required for a job, which has the potential to open up new job positions for an additional 1.4 million workers (Fuller et al. 2022).

Offering better transportation options: Transportation access continues to be an issue for low-income adults and adults in rural areas (Mengedoth 2023). Low-income adults are less likely to own cars and more likely to take public transit. Public transit tends to have longer commute times and can occasionally break down, making it difficult for workers to get to work on time. Investments in more frequent public transportation with wider geographic coverage could support low-income workers’ employment prospects.

Reducing existing work requirements: This is intentionally provocative, but prior sections have described the health and nutrition consequences of failing to gain access to safety net programs like SNAP and Medicaid, such as food and health insecurity, which could be a barrier to work. Further, the existing research base shows near-zero measurable benefit of existing work requirements in promoting work. The upshot of these findings is that it is entirely possible that reducing eligibility barriers to safety net programs—barriers like work requirements—may well be more effective in promoting work than raising those barriers would be. A majority of adults who gained coverage through Medicaid expansion in Ohio and Michigan found that having health care made it easier to find and maintain work (Katch, Wagner, and Aron-Dine 2018).

Conclusion

A key policy trade-off for all welfare state programs is making sure that they reach all eligible populations while avoiding free riders who claim benefits that society and policymakers did not aim to make available to them. When eligibility rules are inclusive and generous, more people will be able to access these programs but with the risk that those who are not meant to be recipients may access these programs anyway. When eligibility rules are stringent and harsh, the likelihood of benefits going to populations not intended to receive them is certainly reduced but at the cost of reducing access to populations all agree the programs are meant to help.

The evidence surveyed above highlights that the U.S. safety net is too stingy and already tilts too hard toward making safety net benefits difficult to access. Further tightening eligibility screens will make this problem worse, with zero tangible benefit in the form of higher levels of employment among low-income adults.

Despite these facts, proponents of work requirements argue that these adults “have no excuse” to not be working since they don’t have children to take care of that live in the home or documented disabilities. Our analysis shows that there are still plenty of barriers that keep low-income adults out of the workforce, including disabilities and the increased likelihood of having an elderly person in the household. Further, we survey the available evidence on work requirements and find that they do not meaningfully increase employment. They ultimately just reduce the number of workers able to access safety net benefits. By picking ABAWDs as the group to be mandated to maintain work requirements, policymakers are effectively identifying a group they view as “least deserving” to access benefits and punishing them with the hope of not receiving a lot of backlash.

We also show that when labor market conditions are right, low-income workers do work and earn more than they do when unemployment is high, suggesting that macroeconomic policy has more to do with ABAWDs’ ability to work than the absence of incentives does. Finally, we outline a wide range of policies that support work for low-income adults and argue these policies would be better at promoting work than any work requirement restriction. If policymakers were serious about creating opportunities to work, they would pass policies like secure scheduling laws and affordable care policies that would meaningfully reduce barriers low-income adults face in gaining employment.

Notes

1. Survey evidence shows that support for work requirements in Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is high—69.8% of adults surveyed in 2022–2023 supported work requirements for Medicaid, and 72.5% supported work requirements for SNAP (Haeder and Moynihan 2023).

2. The Arkansas program was later deemed unconstitutional.

References

Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE). 2016. The Effects of Child Care Subsidies on Maternal Labor Force Participation in the United States. December 2016.

Bauer, Lauren, and Chloe East. 2023. A Primer on SNAP Work Requirements. The Brookings Institution, October 2023.

Bauer, Lauren, Bradley Hardy, and Olivia Howard. 2024. The Safety Net Should Work for Working-Age Adults. The Hamilton Project at The Brookings Institution, April 2024.

Bivens, Josh. 2019. Thinking Seriously About What ‘Fiscal Responsibility’ Should Mean: Full Employment and Reduced Inequality Are the Most Important Targets of Fiscal Policy. Economic Policy Institute, September 2019.

Bivens, Josh, and Ben Zipperer. 2018. The Importance of Locking in Full Employment for the Long Haul. Economic Policy Institute, August 2018.

Butcher, Kristin F., and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach. 2018. Most Workers in Low-Wage Labor Market Work Substantial Hours, in Volatile Jobs. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 2018.

Cai, Julie. 2023. Work-Hour Volatility by the Numbers: How Do Workers Fare in the Wake of the Pandemic? Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Issue Brief 2023-2, September 2023.

Choper, Joshua, Daniel Schneider, and Kristen Harknett. 2021. “Uncertain Time: Precarious Schedules and Job Turnover in the US Service Sector.” ILR Review 75, no. 5: 1099–1132. https://doi.org/10.1177/00197939211048484.

Cohen, Rachel. 2023. “Stop Requiring College Degrees for Jobs That Don’t Need Them: Employers Are Finally Tearing Down the ‘Paper Ceiling’ in Hiring.” Vox, March 19, 2023.

Cook, Jason B., and Chloe N. East. 2024. “The Disenrollment and Labor Supply Effects of SNAP Work Requirements.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper no. 32441, May 2024. https://doi.org/10.3386/w32441.

Crandall-Hollick, Margot L., Gene Falk, and Conor F. Boyle. 2023. The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC): How It Works and Who Receives It. Congressional Research Service, November 2023.

Deshpande, Manasi, and Yue Li. 2019. “Who Is Screened Out? Application Costs and the Targeting of Disability Programs.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 11, no. 4: 213–248.

Economic Policy Institute (EPI). 2024. Current Population Survey Extracts, Version 1.0.59, https://microdata.epi.org.

Farber, Henry S. 2008. “Reference-Dependent Preferences and Labor Supply: The Case of New York City Taxi Drivers.” American Economic Review 98, no. 3: 1069–1082. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles/pdf/doi/10.1257/aer.98.3.1069.

Feng, Wenhui. 2022. “The Effects of Changing SNAP Work Requirement on the Health and Employment Outcomes of Able-Bodied Adults Without Dependents.” Journal of the American Nutrition Association 41, no. 3: 281–290. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07315724.2021.1879692.

Finkelstein, Amy, and Matthew J. Notowidigdo. 2019. “Take-Up and Targeting: Experimental Evidence from SNAP.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 134, no. 3: 1505–1556. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjz013.

Flood, Sarah, Miriam King, Renae Rodgers, Steven Ruggles, J. Robert Warren, Daniel Backman, Annie Chen, Grace Cooper, Stephanie Richards, Megan Schouweiler, and Michael Westberry. 2024. “IPUMS CPS: Version 12.0” [data set]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2024. https://doi.org/10.18128/D030.V12.0.

Fuller, Joseph B., Christina Langer, Julia Nitschke, Layla O’Kane, Matt Sigelman, and Bledi Taska. 2022. The Emerging Degree Reset: How the Shift to Skills-Based Hiring Holds the Keys to Growing the U.S. Workforce at a Time of Talent Shortage. The Burning Glass Institute, 2022.

Fuller, Joseph B., and Manjari Raman. 2017. Dismissed by Degrees: How Degree Inflation Is Undermining U.S. Competitiveness and Hurting America’s Middle Class. Accenture, Grads of Life, Harvard Business School, 2017.

Gornick, Janet C., David Brady, Ive Marx, and Zachary Parolin. 2024. Poverty and Poverty Reduction Among Non-Elderly, Nondisabled, Childless Adults in Affluent Countries: The United States in Cross-National Perspective. The Hamilton Project, The Brookings Institution, April 2024.

Gray, Colin. 2019. “Leaving Benefits on the Table: Evidence from SNAP.” Journal of Public Economics 179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2019.104054.

Gray, Colin, Adam Leive, Elena Prager, Kelsey Pukelis, and Mary Zaki. 2023. “Employed in a SNAP? The Impact of Work Requirements on Program Participation and Labor Supply.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 15, no. 1: 306–341.

Haeder, Simon F., and Donald Moynihan. 2023. “Race and Racial Perceptions Shape Burden Tolerance for Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.” Health Affairs 42, no. 10: 1334–1343. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2023.00472.

Harknett, Kristen, Daniel Schneider, and Véronique Irwin. 2021. “Improving Health and Economic Security by Reducing Work Schedule Uncertainty.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118, no. 42: e2107828118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2107828118.

Herd, Pamela, and Donald P. Moynihan. 2018. Administrative Burden: Policymaking by Other Means. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2018.

Homonoff, Tatiana, and Jason Somerville. 2021. “Program Recertification Costs: Evidence from SNAP.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 13, no. 4: 271–298.

Kalleberg, Arne L. 2009. “Precarious Work, Insecure Workers: Employment Relations in Transition.” American Sociological Review 74, no. 1: 1–22.

Kalleberg, Arne L. 2011. Good Jobs, Bad Jobs: The Rise of Polarized and Precarious Employment Systems in the United States, 1970s to 2000s. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Kalleberg, Arne L. 2012. “Job Quality and Precarious Work: Clarifications, Controversies, and Challenges.” Work and Occupations 39, no. 4: 427–448.

Kalleberg, Arne L., and Peter V. Marsden. 2013. “Changing Work Values in the United States, 1973–2006.” Social Science Research 42, no. 2: 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.09.012.

Katch, Hannah, Jennifer Wagner, and Aviva Aron-Dine. 2018. Taking Medicaid Coverage Away from People Not Meeting Work Requirements Will Reduce Low-Income Families’ Access to Care and Worsen Health Outcomes. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 2018.

Lambert, Susan J., Peter J. Fugiel, and Julia R. Henly. 2014. Precarious Work Schedules Among Early-Career Employees in the US: A National Snapshot. Employment Instability, Family Well-Being, and Social Policy Network at the University of Chicago, 2014.

Maestas, Nicole, Matt Messel, and Yulya Truskinovsky. 2024. “Caregiving and Labor Supply: New Evidence from Administrative Data.” Journal of Labor Economics 42, no. S1. https://doi.org/10.1086/728810.

Mengedoth, Joseph. 2023. Transportation Access as a Barrier to Work. Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Fourth Quarter 2023.

Meyer, Bruce D., and Nikolas Mittag. 2019. “Using Linked Survey and Administrative Data to Better Measure Income: Implications for Poverty, Program Effectiveness, and Holes in the Safety Net.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 11, no. 2: 176–204.

Meyer, Bruce D., Nikolas Mittag, and Robert M. George. 2020. “Errors in Survey Reporting and Imputation and Their Effects on Estimates of Food Stamp Program Participation.” Journal of Human Resources 57, no. 5: 1605–1644. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.58.1.0818-9704R2.

Modestino, Alicia Sasser, Daniel Shoag, and Joshua Ballance. 2016. “Downskilling: Changes in Employer Skill Requirements over the Business Cycle.” Labour Economics 41: 333–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2016.05.010.

Modestino, Alicia Sasser, Daniel Shoag, and Joshua Ballance. 2020. “Upskilling: Do Employers Demand Greater Skill When Workers Are Plentiful?” Review of Economics and Statistics 102, no. 4: 793–805.

Pager, Devah, 2003. “The Mark of a Criminal Record.” American Journal of Sociology 108, no. 5: 937–975.

Posadas, Josefina, and Marian Vidal-Fernandez. 2013. “Grandparents’ Childcare and Female Labor Force Participation.” IZA Journal of Labor Policy 2, no. 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-9004-2-14.

Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center. 2024. “Reduced Administrative Burden for SNAP.” Prenatal-to-3 Policy Clearinghouse Evidence Review. Peabody College of Education and Human Development, Vanderbilt University, October 2024.

Roberts, Lily. 2023. “Work Requirements Are Expensive for the Government to Administer and Don’t Lead to More Employment.” Center for American Progress, April 25, 2023.

Robey, Jason P., Michael Massoglia, and Michael T. Light. 2023. “A Generational Shift: Race and the Declining Lifetime Risk of Imprisonment.” Demography 60, no. 4: 977–1003. https://doi.org/10.1215/00703370-10863378.

Sommers, Benjamin D., Lucy Chen, Robert J. Blendon, E. John Orav, and Arnold M. Epstein. 2020. “Medicaid Work Requirements in Arkansas: Two-Year Impacts on Coverage, Employment, and Affordability of Care.” Health Affairs (Millwood) 39, no. 9: 1522–1530.

Sommers, Benjamin D., Anna L. Goldman, Robert J. Blendon, E. John Orav, and Arnold M. Epstein. 2019. “Medicaid Work Requirements—Results from the First Year in Arkansas.” New England Journal of Medicine 381, no. 11: 1073–1082.

Stacy, Brian, Erik Scherpf, and Young Jo. 2018. “The Impact of SNAP Work Requirements.” Economic Research Service, USDA. Available at: https://www.aeaweb.org/conference/2019/preliminary/paper/Z8ZhzBZt. Cited with permission of the authors. Accessed December 15, 2024.

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). 2024. “SNAP Work Requirements” (web page). Accessed October 22, 2024.

Vericker, Tracy, Laura Wheaton, Kevin Baier, and Joseph Gasper. 2023. “The Impact of ABAWD Time Limit Reinstatement on SNAP Participation and Employment.” Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 55, no. 4: 285–296.

Williams, Jason M., Sean K. Wilson, and Carrie Bergeson. 2019. “It’s Hard Out Here If You’re a Black Felon”: A Critical Examination of Black Male Reentry.” Prison Journal 99, no. 4: 437–458. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032885519852088.

Ziliak, James P. 2013. “Why Are So Many Americans on Food Stamps? The Role of the Economy, Policy, and Demographics.” University of Kentucky Center for Poverty Research Discussion Paper Series, 12. September 2013.

Ziliak, James P. 2015. “Income, Program Participation, Poverty, and Financial Vulnerability: Research and Data Needs.” Journal of Economic and Social Measurement 40, no. 1–4: 27–68. https://doi.org/10.3233/JEM-150397.

Zundl, Elaine, Daniel Schneider, Kristen Harknett, and Evelyn Bellew. 2022. “Still Unstable: The Persistence of Schedule Uncertainty During the Pandemic.” The Shift Project Research Brief. Malcolm Wiener Center for Social Policy at Harvard Kennedy School and the University of California San Francisco.