EPI’s Daniel Costa appeared as a witness and submitted the following written testimony in a hearing before the Subcommittee on Workforce Protections in the United States House Committee on Education and Labor, on Wednesday, July 20, 2022 at 10:15 AM, in the Rayburn House Office Building, room 2175, and via Zoom (hybrid).

Introduction

Thank you to Subcommittee Chair Rep. Adams, as well as Committee Chair Rep. Scott, Ranking Members, and the other distinguished members of the Subcommittee for allowing me to testify at this hearing on the H-2 temporary visa programs and how to better protect workers. I am a researcher at the Economic Policy Institute, a nonprofit, nonpartisan think tank dedicated to advancing policies that ensure a more broadly shared prosperity, and that conducts research and analysis on the economic status of working America and proposes policies that protect and improve the economic conditions of low- and middle-income workers—regardless of their immigration status—and assesses policies with respect to how well they further those goals.

I am especially honored to be before the Subcommittee on Workforce Protections because I am myself the son of two immigrants, each of whom came from a different country and through different immigration pathways, and who met each other in the great melting pot that is my home state of California. My parents I are the direct beneficiaries of the American immigration system—but I also believe that the United States has benefitted greatly from immigration and the immigrants who arrive—both economically and culturally—which is why there is no question in my mind that immigration is good for the United States. It’s also why I believe that the United States should grow and expand pathways for immigrants to come and stay and integrate into the United States, and believe we should do much more to improve the migration pathways that currently exist.

The purpose of this hearing is to discuss two of the most well-known and important work visa programs in the United States, the H-2A visa program—for temporary and seasonal jobs in agriculture—and the H-2B program—for temporary and seasonal jobs outside of agriculture. This hearing is timely and of utmost importance because in recent years, the size of both programs has increased rapidly—but during those years—few, if any, new protections have been implemented to ensure that workers in those programs are adequately protected from abuses like wage theft and trafficking. Congress and federal agencies have failed to implement those measures despite numerous and egregious cases of worker abuse, exploitation, human trafficking, and even deaths.

In the broadest terms, I wish to note at the outset that U.S. workers should have certain rights vis-à-vis the U.S. temporary work visa programs. First, they should have the right to have a fair and first shot at job openings in the United States. Second, U.S. workers should have the right to be protected from competition with workers who are paid artificially low wages that are the result of corporate exploitation of the immigration system. And migrant workers who are recruited to the United States to fill job openings should also have certain rights. They should have the right to be free from paying fees to the recruiters who connect them to jobs in the United States. They should have the right to leave an abusive or law-breaking employer without fearing retaliation and deportation. And they should have the right to be paid no less than the local average wage for the jobs they fill, according to U.S. wage standards. And importantly—because of the exploitative nature of temporary work visa programs—migrant workers should have an opportunity to stay permanently and continue to contribute to the United States, by having access to a quick path to permanent residence and citizenship—and it should be a path that that the migrant controls, not one that is controlled by employers.

Unfortunately, when it comes to the H-2A and H-2B visa programs, the U.S. government is failing to meet these basic standards and provide these basic rights to U.S. workers and migrant workers in the H-2A and H-2B visa programs.

My testimony will discuss the flaws that are common across U.S. temporary work visa programs and offer common sense solutions, and present the available data about the H-2A and H-2B visa programs in terms of their size and workplace abuses and wage theft. It will also suggest executive and congressional reforms that should be implemented. Because other witnesses in this hearing will discuss the H-2A program in depth, the recommendations specific to H-2 in my testimony will focus mainly on the H-2B program.

U.S. temporary work visa programs

Nearly all immigrants, refugees, and asylum-seekers join the workforce after entering the United States, but a portion of our immigration system is intended to bring people here expressly for work. Within that complex employment-based system, the majority of migrants come through temporary, precarious pathways—known as temporary work visa programs—that provide employers with millions of on-demand workers who have limited rights, and whose needs and realities are not well understood, even by mainstream immigration advocates.

While temporary work visa programs represent a major component of the U.S. immigration system, less is known about them compared with other aspects of the system that garner more public attention. Nonetheless, work visa programs have played an outsized role in political and policy debates about how to reform the immigration system in the past, and likely will again.

Temporary work visa programs are an instrument ultimately used to deliver migrant workers to employers, but without having to afford them equal rights, dignity, or the opportunity to integrate and participate in political life. While such programs may serve as important pathways for migrants to come to the United States, the numerous programmatic flaws that undermine labor standards and leave migrant workers vulnerable to abuses—and even human trafficking—clearly demonstrate a need for dramatic improvements.

This is not news; migrant worker advocates, government auditors, and the media have identified these flaws across U.S. temporary work visa programs for decades. Most of the workers who participate in the programs will never have a chance to become lawful permanent residents or naturalized citizens, despite spending months, and in many cases, years, working in the United States. The COVID-19 pandemic and the national emergency that was declared on March 13, 2020,1 along with the inadequacy of the federal government’s response, have only exacerbated the challenges migrant workers face while employed through temporary work visa programs, many of which continue today.

Despite the popular narrative that former President Trump’s administration instituted a so-called immigration crackdown on all pathways into the United States, temporary work visa programs were a clear exception. Even before the pandemic began, important immigration pathways that can lead to permanent residence and citizenship had been slashed by the Trump administration—and humanitarian pathways for asylees and refugees in particular had already been reduced to historic lows. But, at the same time, data show that temporary work visa programs were 13% larger in 2019 than during the last year of the Obama administration. Even the Trump administration’s temporary work visa “ban” issued in June 2020 in retrospect looks to have been mostly symbolic—a political tactic to blame migrants for high unemployment and the economic collapse that resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic. This point in history was a dangerous trajectory away from welcoming immigrants as persons who have equal rights and who can settle in the United States permanently and toward using the immigration system mostly to appease the desire employers have for more indentured and disposable migrant workers. Today, the Biden administration is still attempting to reconstitute much of the immigration system that was torn down by the Trump administration. Numerous reports have shown that staffing shortages and backlogs have led to the wasting—in other words the non-issuance of—green cards that should have been issued to people who have been waiting for years to become permanent immigrants to the United States.

When it comes to U.S. labor migration pathways, they can and should be reformed to comport with universal human and labor rights standards. Many major improvements to temporary work visa programs can be accomplished by the executive branch through regulations, new guidance, and other executive actions, as my testimony will discuss. Nevertheless, the reality remains that some of the most transformative and lasting solutions will require congressional action, and those reforms will also be disused herein. An added benefit of these more durable solutions is that they will set a useful baseline of protections for temporary migrant workers, both in normal times and during emergencies like pandemics, and during both periods of high unemployment and tight labor markets.

Now is the moment for policymakers to take stock of the immigration system and implement needed reforms to employment-based migration pathways. And considering that a record number of temporary migrant workers are employed in the United States—more than 2 million, with many performing jobs that have now been deemed “essential”—the need to protect these workers has never been more acute.

The basics: What are temporary work visa programs?

One of the main authorized or “legal” pathways for U.S. employers that wish to hire migrant workers or for migrants who want to work in the United States lawfully is via “nonimmigrant” visas that authorize temporary employment. In the United States, employers almost exclusively control and drive the process, by deciding to recruit and hire employees through temporary work visa programs. Workers who participate in those programs are known as temporary migrant workers, or “guestworkers”—defined as persons employed away from their home countries in temporary labor migration programs. The programs themselves are often referred to as circular or “guest” worker programs, or temporary work visa programs.2 Temporary and home can be defined in different ways, with “temporary” ranging from several months to several years, and “home” usually meaning the worker’s country of birth or citizenship.3 All temporary work visa programs require migrant workers to return to their home countries when their visa expires; workers can remain legally in the United States only if they obtain another temporary visa or lawful permanent resident status.

The most common argument for using temporary work visa programs to facilitate migration is that they help employers fill vacant jobs, especially when employers assert there is a shortage of U.S. workers, in other words, to fill labor shortages. Other major rationales include (1) to facilitate youth exchange programs and admit foreign students (in both cases, the migrants are usually permitted to work); (2) to allow intracorporate transfers (sometimes called intracompany transfers), meaning that employees of multinational companies move from a branch or office of a company to another branch or office of the same company in a different country; (3) to fulfill trade agreement provisions, such as those included in agreements like the North American Free Trade Agreement; (4) to facilitate foreign investment in countries of destination; (5) to manage migration that would otherwise be inevitable—for example, as the result of geopolitical changes; and (6) to allow for cross-border commuting.4

According to the Congressional Research Service, “there are 24 major nonimmigrant visa categories, which are commonly referred to by the letter and numeral that denote their subsection in the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA)”5; over the past few years, between 9 million and 11 million total nonimmigrant visas have been issued. While the vast majority of these were visitor visas that do not authorize employment, nevertheless hundreds of thousands of new nonimmigrant visas in an alphabet soup of temporary work visa programs have been issued to migrant workers or renewed; in addition, the United States has approved work permits for nonimmigrants in visa classifications that do not automatically authorize employment.

Some work visa programs have an annual numerical limitation. For example, the H-2B visa is capped at 66,000 per year; the H-1B visa is capped at 85,000 for the private sector—although it also allows an unlimited number not subject to the annual cap for certain employers.6 However, most work visa programs do not have an annual numerical limit. Each visa program has a different duration of stay associated with it, as well as individual rules about whether and how it can be renewed. For example, H-2A visas for temporary and seasonal agricultural occupations are valid for up to one year, depending on the duration of the job, but can sometimes be renewed, while H-1B visas for occupations that require a college degree may be valid for up to three years, renewable once for a total of six years, and L-1 visas for intracompany transferees may last up to five years for a position that requires specialized knowledge about the employer, or seven years if the worker is a manager or executive.

The Pew Research Center has estimated that approximately 5% of the total foreign-born population are temporarily residing in the United States with nonimmigrant visas.7 Although good data are lacking from the U.S. government on the exact number of nonimmigrant residents who are employed, and in which visa programs, I have estimated that more than 2 million temporary migrant workers were employed in 2019, accounting for 1.2% of the U.S. labor force (see discussion in the following section).8

The numbers in context: Temporary work visa programs grew under Trump, while permanent pathways shrunk and have not yet been fully restored

Despite the popular narrative that the former Trump administration instituted an “immigration crackdown” on all pathways into the United States, temporary work visa programs were a clear exception. Other, permanent immigration pathways that can lead to citizenship were slashed—even before the pandemic began—including the number of refugees admitted being reduced to a historic low and asylum being severely restricted9—but this has not been the case with temporary work visa programs.

The main factor impacting the issuance of both permanent and temporary visas since the COVID-19 pandemic has been the slowdown and shutdown of consular processing for visas around the world, along with staffing shortages at United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), and the impact is still being felt today in mid-2022. In any case, the shift to more temporary work visas and fewer permanent immigrant visas during the Trump administration was a significant and dangerous trajectory away from welcoming immigrants who would be granted equal rights and the ability to settle in the United States permanently; it reflects an immigration system used mainly to appease the business community’s demands for more migrant workers who are indentured to them and disposable.10

Table 1 below shows an estimate of the number of temporary migrant workers employed in 2016 and in 2019, the year before the disruptions to the immigration system caused by the pandemic, based on an updated version of the methodology devised by Costa and Rosenbaum.11 It reveals that the number of temporary migrant workers employed during 2019 was nearly 2.1 million—over 237,000 more than during the last year of the Obama administration, or a 13% increase. In total these workers represented 1.2% of the U.S. labor market in 2019. Much of the increase was driven by growth in the visa programs for low-wage jobs—H-2A, H-2B, and J-1—but also by growth in a number of the visa programs for migrant workers who normally possess at least a college degree, including H-1B visas (for information technology jobs), the Optional Practical Training program for foreign graduates with F-1 visas, L-1 visas for intracompany transferees, and O-1 and O-2 visas for persons with extraordinary abilities.

Temporary work visa programs grew 13% under Trump: Estimated number of temporary migrant workers employed in the United States, 2016 and 2019

| Number of workers employed | ||

|---|---|---|

| Nonimmigrant visa classification | 2016 | 2019 |

| A-3 visa for attendants, servants, or personal employees of A-1 and A-2 visa holders | 2,162 | 1,687 |

| B-1 visa for temporary visitors for business | 3,000 | 3,000 |

| CW-1 visa for transitional workers on the Commonwealth of Northern Mariana Islands | 8,093 | 3,263 |

| F-1 visa for foreign students, Optional Practical Training program (OPT) and STEM OPT extensions | 199,031 | 223,308 |

| G-5 visa for attendants, servants, or personal employees of G-1 through G-4 visa holder | 1,309 | 945 |

| E-1 visa for treaty traders and their spouses and children | 8,085 | 6,668 |

| E-2 visa for treaty investors and their spouses and children | 66,738 | 66,738 |

| E-3 visa for Australian specialty occupation professionals | 15,628 | 16,858 |

| H-1B visa for specialty occupations | 528,993 | 583,420 |

| H-2A visa for seasonal agricultural occupations | 134,368 | 204,801 |

| H-2B visa for seasonal nonagricultural occupations | 149,491 | 160,410 |

| H-4 visa for spouses of certain H-1B workers | 54,936 | 74,749 |

| J-1 visa for Exchange Visitor Program participants/workers | 193,520 | 222,597 |

| J-2 visa for spouses of J-1 exchange visitors | 10,147 | 11,781 |

| L-1 visa for intracompany transferees | 316,224 | 337,164 |

| L-2 visa for spouses of intracompany transferees | 25,670 | 25,673 |

| O-1/O-2 visa for persons with extraordinary ability and their assistants | 38,706 | 47,725 |

| P-1 visa for internationally recognized athletes and members of entertainment groups | 24,262 | 25,601 |

| P-2 visa for artists or entertainers in a reciprocal exchange program | 97 | 107 |

| P-3 visa for artists or entertainers in a reciprocal exchange program | 8,426 | 9,848 |

| TN visa or status for Canadian and Mexican nationals in certain professional occupations under NAFTA | 50,000 | 50,000 |

| Total | 1,838,886 | 2,076,343 |

Notes: Methodology for calculating the number of workers derived from Daniel Costa and Jennifer Rosenbaum, Temporary Foreign Workers by the Numbers: New Estimates by Visa Classification, Economic Policy Institute, March 2017. All references to a particular year should be understood to mean the U.S. government’s fiscal year (Oct. 1–Sept. 30).

Sources

Bureau of Consular Affairs, “Nonimmigrant Visa Statistics,” U.S. Department of State; USCIS, “Form I-765 Application for Employment Authorization, All Receipts, Approvals, Denials Grouped by Eligibility Category and Filing Type, Fiscal Year 2019”; H-1B Authorized-to-Work Population Estimate, Office of Policy and Strategy, Research Division, June 2020; Daniel Costa and Jennifer Rosenbaum, Temporary Foreign Workers by the Numbers: New Estimates by Visa Classification, Economic Policy Institute, March 2017; Letter from Sen. Grassley to Attorney General Lynch and Secretaries Johnson, Kerry, and Perez, June 7, 2016; U.S. Government Accountability Office, Nonimmigrant Investors: Actions Needed to Improve E-2 Visa Adjudication and Fraud Coordination, GAO-19-577, July 2019; Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates, “J-1 Physicians: Essential to U.S. Health Care” (infographic), Oct. 9, 2020.

Growth in temporary work visa programs is part of a long-term trend

While temporary work visa programs expanded during the Trump administration, the growth of the programs represented a continuing long-term trend dating back more than 30 years. Figure A shows the number of new visas issued in 36 nonimmigrant visa classifications that represent U.S. temporary work visa programs, or programs that allow spouses and children to accompany the principal temporary migrant worker, between 1987 and 2019.12 For comparison, the figure also shows the number of permanent immigrant visas issued in the employment-based (EB) green card preferences—i.e., green cards issued for the purpose of work, which allow migrants to adjust to become lawful permanent residents—over the same period. The dotted line in Figure A shows the point at which the last major immigration reform was passed in the United States, in November 1990, when the Immigration Act of 1990 (commonly referred to as IMMACT90) was enacted.

Employment-based permanent immigrant visas and temporary nonimmigrant work visas issued, including principal and derivative beneficiaries, 1987–2019

| Temporary work visas | Employment-based LPR | |

|---|---|---|

| 1987 | 245,645 | 57,519 |

| 1988 | 261,712 | 58,727 |

| 1989 | 296,598 | 57,741 |

| 1990 | 315,369 | 58,192 |

| 1991 | 328,985 | 59,525 |

| 1992 | 325,155 | 116,198 |

| 1993 | 340,060 | 147,012 |

| 1994 | 375,207 | 123,291 |

| 1995 | 414,434 | 85,336 |

| 1996 | 429,580 | 117,499 |

| 1997 | 492,600 | 90,607 |

| 1998 | 539,221 | 77,517 |

| 1999 | 624,899 | 56,678 |

| 2000 | 727,234 | 106,642 |

| 2001 | 815,944 | 178,702 |

| 2002 | 785,802 | 173,814 |

| 2003 | 809,657 | 81,727 |

| 2004 | 915,188 | 155,330 |

| 2005 | 862,659 | 246,877 |

| 2006 | 961,855 | 159,081 |

| 2007 | 1,103,767 | 162,176 |

| 2008 | 1,061,182 | 164,741 |

| 2009 | 883,654 | 140,903 |

| 2010 | 937,404 | 148,343 |

| 2011 | 960,223 | 139,339 |

| 2012 | 992,446 | 143,998 |

| 2013 | 1,072,981 | 161,110 |

| 2014 | 1,163,160 | 151,596 |

| 2015 | 1,235,196 | 144,047 |

| 2016 | 1,356,459 | 137,893 |

| 2017 | 1,414,241 | 137,855 |

| 2018 | 1,406,139 | 138,171 |

| 2019 | 1,491,209 | 139,458 |

Notes: The Immigration Act of 1990 was enacted on November 29, 1990. LPR stands for lawful permanent resident. Employment-based LPR refers to permanent immigrant visas in the employment-based preference categories, which confer permanent residence on the migrant beneficiary. For more background on employment-based permanent immigrant visas, see USCIS, “Permanent Workers,” Working in the United States, last reviewed/updated Jan. 9, 2020.

Data shown in the figure include employment-based immigrant visas, preference categories 1–5, and nonimmigrant visas in the A-3, CW-1, CW-2, E-1, E-2, E-2C, E-3, E-3D, E-3R, F-1/OPT, G-5, H-1, H-1A, H-1B, H-1B1, H-1C, H-2, H-2A, H-2B, H-4, J-1, J-2, L-1, L-2, O-1, O-2, O-3, P-1, P-2, P-3, P-4, Q-1, R-1, R-2, TN, and TD classifications.

Source

Author’s analysis of U.S. Department of State, Nonimmigrant Visa Statistics; Interagency Working Group on U.S. Government-Sponsored International Exchanges and Training; U.S. Department of State, J-1 Visa Website; Office of Immigration Statistics, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, U.S. Department of Homeland Security (various years); Government Accountability Office, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands: DHS Implementation of Immigration Laws, Statement of David Gootnick, Director, International Affairs and Trade, GAO-19-376T (February 27, 2019); U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, “International Student and Exchange Visitor Data,” Student and Exchange Visitor Program Data Library; USCIS, I-765 approval data, various years, USCIS Electronic Reading Room.

The major trends that have occurred since IMMACT90’s enactment were that issuances of EB green cards increased slowly until stabilizing around the new annual cap for EB green cards of 140,000 (created by IMMACT90), while the number of temporary work visas issued increased exponentially during the same period. In 2019, the number of EB green cards issued represented only 8.6% of all new work visas issued to migrant workers and their families (temporary plus EB green cards). These data show that the labor migration pathways available to migrant workers and their families in the U.S. immigration system are almost exclusively temporary.13

The difference under Trump was that the steady growth in temporary work visa programs occurred while the Trump administration simultaneously, and successfully, made unprecedented moves to slash virtually every permanent immigrant pathway available in the U.S. system. Despite the Biden administration’s stated commitments to restore the immigration system, budget and staffing shortfalls at USCIS have led to many of the green cards available in permanent categories from not being issued, and many are in danger of not being issued again by the end of fiscal year 202214. In terms of reestablishing humanitarian pathways, while the Biden administration raised the refugee cap significantly to 125,000 for fiscal year 2022, statistics suggest that federal agencies will not come close to processing that many refugee visas in 2022.15

Temporary migrant workers face unique challenges due to program frameworks

As discussed above, the U.S. labor migration system has shifted towards one that increasingly provides only temporary pathways to work. Yet, although migrants coming to the United States through temporary work visa programs are legally authorized to work, they are among the most exploited laborers in the U.S. workforce because employer control of their visa status leaves many powerless to defend and uphold their rights. Rather than being an issue of a few bad employers, the flaws in temporary work visa programs are systemic and structural. The list below summarizes some of the most problematic aspects of temporary work visa programs and how they impact workers.

Illegal recruitment fees and debt bondage are common

Temporary migrant workers can face abuse even before arriving in the United States: Many are required to pay exorbitant fees to labor recruiters to secure U.S. employment opportunities, even though such fees are usually illegal.16 Those fees leave them indebted to recruiters or third-party lenders, which can result in a form of debt bondage.17(Even migrants recruited to work with employment-based green cards have ended up paying exorbitant fees, as seen in one case reported in ProPublica, in which a Korean worker paid $26,000 to a recruitment agency to work in a poultry processing plant.18) After arriving in the United States, temporary migrant workers may find out the jobs they were promised don’t exist.19 And in a number of cases, temporary migrant workers have become victims of human trafficking—with some being forced to work in the sex industry.20

Contrary to popular belief, it’s not just farmworkers and other temporary migrant workers in low-wage jobs suffering from the abuses that pervade temporary work visa programs: College-educated workers in computer occupations, as well as teachers and nurses, have been victimized and put in “financial bondage” by shady recruiters and staffing firms that steal wages, forbid workers from switching jobs or taking jobs the recruiters don’t financially benefit from, and file lawsuits against workers if they try to change jobs or quit.21

Temporary work visa programs permit employers to circumvent U.S. anti-discrimination laws and segregate the workforce

While U.S. anti-discrimination laws are intended to make workplaces fairer and more equal by prohibiting discrimination in hiring and employment on the basis of factors like race, color, sex, religion, and national origin at the point of hire—in practice they don’t apply to temporary migrant workers who are recruited abroad. Because workers are being selected by recruiters in countries of origin, outside of U.S. jurisdiction, employers have the ability to reclassify entire sectors of the U.S. workforce by race, gender, national origin, and age through temporary work visa programs.22

This occurs through recruiters and employers limiting access to jobs made available to workers based on employer preferences for national origin, gender, and age, allowing them to sort workers into occupations and visa programs based on racialized and gendered notions of work. Thanks to temporary work visa programs, an employer may select an entire workforce composed of a single nationality, gender, or age group—for example, selecting only young Mexican men for farm jobs with H-2A visas, or young Indian men to work as computer programmers with H-1B visas, or young women from Eastern Europe for work in restaurants and amusement parks with J-1 visas. The large shares of visas issued to specific countries of origin, and the limited demographic data available, provide evidence that this is occurring,23 and websites exist that allow employers to browse the profiles of workers on employment agency websites that advertise workers like commodities.24

Employers and recruiters can also weed out workers who might dare to speak out against unlawful employment practices, assert their legal rights, or organize for better working conditions by joining or forming a union. They can do this by refusing to hire workers whom they think will be likely to complain, and retaliating against workers who do speak up or complain—for instance, by firing them and effectively forcing them to leave the country, or by threatening to blacklist them from being hired for future job opportunities.

The visa status of temporary migrant workers is usually tied to their employer, thus chilling labor rights, preventing mobility, and enabling employer lawbreaking

The many temporary migrant workers who are in debt after paying recruitment fees are anxious to earn enough to pay back what they owe and hopefully make a profit, and are thus unlikely to speak up at work when things go wrong on the job. But even those who aren’t caught in the debt trap are often subject to exploitation once they are working in the United States. Like unauthorized immigrants, temporary migrant workers have good reason to fear retaliation and deportation if they speak up about wage theft, workplace abuses, or other working conditions like substandard health and safety procedures on the job—not because they don’t have a valid immigration status, but because their visas are almost always tied to one employer that owns and controls their visa status. That visa status is what determines the worker’s right to remain in the country; if they lose their job, they lose their visa and become deportable. This arrangement results in a form of indentured servitude.25 Further, as noted in the previous section, employers can punish temporary migrant workers for speaking out by not rehiring them the following year or by telling recruiters in countries of origin that they shouldn’t be hired for other job opportunities in the United States (effectively blacklisting them).26

The specter of retaliation makes it understandably difficult for temporary migrant workers to complain to their employers and to government agencies about unpaid wages and substandard working conditions. Private lawsuits against employers who break the law are also an unrealistic avenue for enforcing rights, for two reasons: First, most temporary migrant workers are not eligible for federally funded legal services under U.S. law, and second, those who have been fired are unlikely to have a valid immigration status permitting them to stay in the United States long enough to pursue their claims in court. Because of the conditions created by tying workers to a single employer through their visa status, temporary work visa programs have been dubbed by some as “close to slavery” or “the new American slavery,” and government auditors have noted that increased protections are needed for temporary migrant workers.27

While temporary migrant workers generally cannot easily change jobs or employers, the terms and conditions of some nonimmigrant visas for college-educated workers actually do permit them to change employers—in particular the J-1, F-1 Optional Practical Training (OPT) program, H-1B, and TN visas allow workers to change employers—although the rules vary even among these visas. In the J-1 visa, which is managed by the State Department, there are sponsor organizations that partner with the State Department to manage oversight and compliance. Those private organizations act as middlemen between the J-1 workers and U.S. employers, and ultimately must sign off on a job change for a J-1 worker, rendering it difficult in practice. In the F-1/OPT context, universities play a key role and ultimately approve employment for OPT workers but exercise little oversight, sometimes resulting in abuses.28

It is important to stress that temporary migrant workers in these four visa programs that allow for some portability have nevertheless been subjected to substandard workplace conditions, and been the victims of fraud and even trafficking, which suggests that the ability to change employers, on its own, is not a panacea for protecting temporary migrant workers. Allowing temporary migrant workers to change employers is something that some proponents of expanded temporary work visa programs—like researchers from the Center for Global Development and the Cato Institute29—have proposed in lieu of additional labor standards enforcement. But the legal ability to change jobs does not alone provide protection from exploitation; while this is a pervasive assumption in basic economics, it is a generally incorrect assumption that is finally being called into question.30 The ability to change employers should be a basic fundamental freedom for workers, not an excuse to abandon labor standards enforcement.

Temporary migrant workers are often legally underpaid

There is abundant evidence that the laws and regulations governing major temporary work visa programs—such as H-2B and H-1B—permit employers to pay their temporary migrant workers much less than the local average wage for the jobs they fill.31 For example, in the H-1B visa program—which has a prevailing wage rule that is intended to protect local wage standards—60% of all H-1B jobs certified by the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) in 2019 were certified at a wage that was below the local average wage for the specific occupation.32 And despite the wage rules in H-1B, there is evidence that wage theft of H-1B workers may be occurring on a massive scale.33

However, most work visa programs have no minimum or prevailing wage rules at all—perhaps that’s why some employers have believed they could get away with vastly underpaying their temporary migrant workers, as one Silicon Valley technology company in Fremont, California, did by paying less than $2 an hour to skilled migrant workers from India on L-1 visas who were working up to 122 hours per week installing computers.34

While employers are still required by law to pay temporary migrant workers at least the state or federal minimum wage, that’s often far less than the true market rate, or the local average wage, for the occupation in which they are employed. The company employing the L-1 workers in Fremont who were paid less than $2 an hour was cited for violations by DOL because California law required that they be paid no less than $8 an hour (the state minimum wage at the time), plus time-and-a-half for overtime. But the average wage in Fremont for the job they were doing—installing computers—was $20 per hour at the time according to DOL data, and if they were also configuring the computers for the company’s network, the going rate for their work would have been $44 per hour.35 In the end, the company was required to pay back wages of $40,000 plus a fine of $3,500 “because of the willful nature of the violations”—a slap on the wrist considering the egregiousness of the wage theft, and hardly a disincentive against future violations.36

Considering how the wage rules or lack thereof in these programs operate, and the situation workers are left in, perhaps it is no surprise there is evidence that temporary migrant workers in low-wage jobs earn approximately the same wages, on average, that unauthorized immigrant workers do for similar jobs, despite the fact that unauthorized workers have virtually no rights in practice.37 In other words, these temporary migrant workers do not have any financial incentive to work legally through visa programs since there is no wage premium to be gained for it—and, in fact, authorized temporary migrant workers can end up worse off economically than unauthorized workers because of the debts they incur through fees paid to recruiters, and considering the fact that they may have no family or social networks to rely on. This could ultimately result in incentivizing workers to migrate without authorization, rather than using available legal channels.

In essence, these visa programs operate in practice to create a labor market monopsony for employers—awarding employers greater leverage over their workers38—and growing research has shown that even modest amounts of employer monopsony power are utterly corrosive to workers’ ability to bargain for better wages.39

Oversight is lacking, leaving temporary migrant workers unprotected

There is very little oversight of temporary work visa programs by DOL. In fact, most of the programs have no rules in place at all to protect temporary migrant workers after they arrive in the United States. Where such rules are in place—namely in the H-1B, H-2A, and H-2B programs—enforcement is inadequate to protect workers, and companies that are frequent and extreme violators of the rules are often allowed to continue hiring through visa programs with impunity.40 Part of the problem lies with DOL’s weak legal mandate, but is also due to the reality of DOL being woefully underfunded and understaffed. In fact, funding for DOL’s Wage and Hour Division (WHD) and Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has remained flat over the past decade, while the number of workers they are responsible for protecting has increased sharply.41 To put that into context, consider that in 2018, the budget for labor standards enforcement across all federal U.S. agencies was only $2 billion, while spending on immigration enforcement in 2018 was $24 billion, an astonishing 11 times greater than spending to enforce labor standards—despite the mandate labor agencies have to protect 146 million workers employed at 10 million workplaces.42 Consider as well that the Wage and Hour Division—the division at DOL in charge of enforcement in the H visa programs—had fewer investigators on staff in 2019 than it did almost five decades earlier, which explains the agency’s limited capacity to conduct investigations.43

Most temporary migrant workers cannot transition to a permanent immigrant status; in the few programs that offer a pathway, it is controlled by employers

None of the U.S. temporary work visa programs provide for an automatic path to lawful permanent residence—i.e., obtaining a “green card”—which would also allow them to eventually qualify for naturalization (citizenship) after a few years, nor do they allow for a quick and direct path for temporary migrant workers to apply for green cards themselves. As a result, many temporary migrant workers return to the United States every year for decades in a nonimmigrant status, often for six to nearly 12 months at a time—rendering them permanently temporary in many respects—which also impacts their ability to integrate into the United States and prevents them from earning the higher wages associated with permanent residence and citizenship.44

Only two temporary work visa programs allow for a relatively straightforward application process for green cards, the H-1B and L-1 visas. But in those programs, it is the employer who decides whether the worker should get a green card; the employer also controls the green card application and process. This creates an imbalance of power between temporary migrant workers and their employers that allows employers to exert undue influence over the lives of their workers with visas, and disincentivizes workers from speaking up about workplace abuses, as speaking up could jeopardize their ability to remain in the United States.

Even when employers decide to apply for green cards for the temporary migrant workers who are eligible, workers can end up in what’s known as the green card “backlog,” waiting years and even decades for a green card to become available to them. The Congressional Research Service has estimated that approximately 1 million temporary migrant workers are in the green card backlog.45 During their time in the backlog, workers can experience an employment relationship that is ripe for exploitation, because workers are unable to switch easily between jobs or employers by virtue of their prolonged temporary status.

Many temporary migrant workers are separated from their families while employed in the United States

While many temporary work visa programs technically allow migrant workers to bring their spouses and children, in most cases U.S. visa rules do not authorize spouses to work—making it difficult, if not impossible, for spouses and children to accompany workers because of the high cost of living and low pay in work visa programs. Taking into consideration that so many temporary migrant workers return every year for decades, workers and their family members can end up facing prolonged separation and trauma—children may grow up hardly knowing, or ever seeing, one or both of their parents.

The H-2A and H-2B visa programs: Recent, rapid growth

While the preceding sections discussed issues that cut across all U.S. temporary work visa programs, the following sections will focus on the H-2A and H-2B visa programs.

H-2A and H-2B are two of many U.S. temporary work visa programs. 46 The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 first created some of the current temporary work visas, including the H-2 visas for foreign nationals “coming temporarily to the United States to perform other temporary services or labor, if unemployed persons capable of performing such service or labor cannot be found in this country.”47 In 1986, the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) split the H-2 visa into two separate visas, the H-2A for temporary workers employed in agricultural occupations and H-2B for temporary workers in occupations outside of agriculture.48 H-2A is explicitly for temporary and seasonal jobs in agriculture, and in practice mostly used for crop farming, and the H-2B program is intended to be used when non-agricultural employers face labor shortages in seasonal jobs. The most common occupations in H-2B are landscaping, construction, forestry, seafood and meat processing, traveling carnivals, restaurants, and hospitality. The H-2A visas program has no annual numerical limit or “cap.” In H-2B however, legislation enacted subsequent to IRCA, the Immigration Act of 1990, established an annual numerical limit of 66,000 H-2B visas that could be issued annually, and which took effect in fiscal year 1992.49 This annual numerical limit of 66,000 visas is often referred to as the H-2B annual “cap.”

In this section I will begin with a discussion about the current size of both programs. The H-2A program has expanded rapidly over the past decade and the H-2B visa program, despite the annual cap of 66,000 per fiscal year, has grown quickly since 2016, when Congress began to include riders to create supplemental visas beyond the H-2B annual cap.

The size of the H-2A program has tripled over the past decade, and over half of jobs are located in just five states

As Figure B shows below—whether by the number of jobs certified by the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) or the number of visas issued by the State Department—the size of the H-2A program has more than tripled over the last decade. In 2012, DOL certified 85,248 jobs for H-2A, and in 2021, there were 317,619 certified jobs. In 2012, the State Department issued 65,345 H-2A visas, and in 2021, issued 257,898.

H-2A jobs certified and visas issued, 2005—2021, and petitions approved, 2015—2021

| Year | Jobs Certified | Visas Issued | Petitions Approved |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 48,336 | 31,892 | |

| 2006 | 59,110 | 37,149 | |

| 2007 | 76,814 | 50,791 | |

| 2008 | 82,099 | 64,404 | |

| 2009 | 86,014 | 60,112 | |

| 2010 | 79,011 | 55,921 | |

| 2011 | 77,246 | 55,384 | |

| 2012 | 85,248 | 65,345 | |

| 2013 | 98,821 | 74,192 | |

| 2014 | 116,689 | 89,274 | |

| 2015 | 139,832 | 108,144 | 154,262 |

| 2016 | 165,741 | 134,368 | 175,171 |

| 2017 | 200,049 | 161,583 | 215,079 |

| 2018 | 242,762 | 196,409 | 279,482 |

| 2019 | 257,667 | 204,801 | 302,422 |

| 2020 | 275,430 | 213,394 | 308,877 |

| 2021 | 317,619 | 257,898 | 339,314 |

Notes: All references to a particular year should be understood to mean the U.S. government’s fiscal year (October 1–September 30).

Source: U.S. Department of Labor, Office of Foreign Labor Certification, OFLC Performance Data; U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs, “Nonimmigrant Visa Statistics”; U.S. Department of Homeland Security, United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, H-2A Employer Data Hub.

Because three separate agencies are involved in managing the H-2A visa program, it is difficult to know the exact number of H-2A workers employed in the United States: DOL reviews and adjudicates applications for job certifications, USCIS in the Department of Homeland Security reviews and adjudicates petitions, and State issue or denies visas. This leads to three separate data sources which offer a different picture of the size of the program (see the three lines on the chart in Figure B).

In my opinion, the best methodology for estimating the size of the H-2A workforce is to add the number of new visas issued by State and adding the number of H-2A approvals for continuing employment (in other words, visa extensions) by USCIS.50 This is because H-2A visas issued represent new H-2A workers and extensions by USCIS represent H-2A workers who did not leave the United States because USCIS approved them to remain and continue working at their job.

In 2021, State issued 257,898 visas. USCIS H-2A employer data hub shows there were 43,020 approved petitions for continuing employment, leading to a total of 300,918 H-2A workers employed in 2021. According to 2020 labor certification from DOL, we know that on average, H-2A jobs were certified for 168 days, which is just under six months.51 Since each H-2A job is certified on average for six months, that means that 300,918 six-month H-2A jobs is equal to 150,459 full-time equivalent jobs filled with H-2A workers.

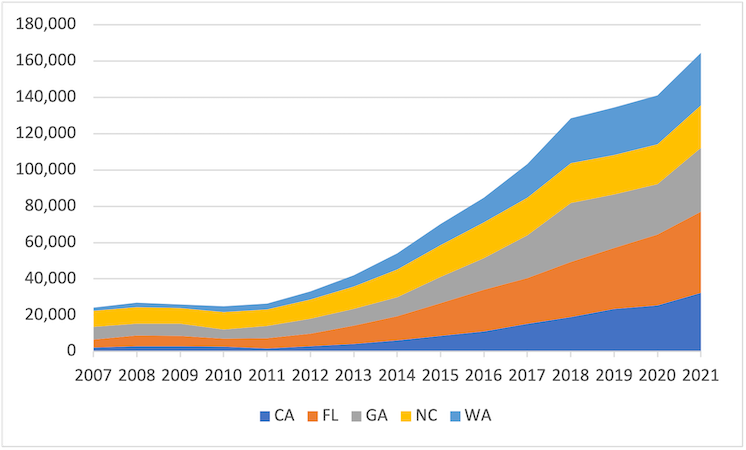

Finally, Figure C from Rural Migration News at the University of California, Davis, shows that over half of the H-2A jobs certified by DOL had worksites located in just five states: California, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Washington.52 The share of H-2A jobs that these states accounted for rose from 34% in 2007 to 52% in 2021, meaning that much of the growth in the H-2A program has been accounted for by the growth in these five states in the southeast and west.

The top five states had 52% of H-2A jobs in Fiscal Year 2021; in California and Washington H-2A rose the fastest

Note: Numbers represent approved job certifications for H-2A by the Office of Foreign Labor Certification in the Employment and Training Administration, U.S. Department of Labor, in five states: California, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Washington.

Source: Figure reproduced with permission from author. Rural Migration News, "The H-2A Program in 2022," University of California, Davis, May 16, 2022.

New data reveal the size of the H-2B program in 2021 nearly equaled its record high

While, as noted above, the annual cap for the H-2B program has been set in law at 66,000 since 1992, in recent years the number of H-2B workers has been much higher, due mostly to congressionally authorized increases every year, along with extensions and exemption from the cap. The first temporary modification to the H-2B cap occurred during fiscal years 2005-2007, when Congress passed a law putting in place a temporary “returning worker exemption” during those years that allowed migrant workers who had been employed with an H-2B visa in any one of the previous three fiscal years to not be counted against the annual cap. As a result, the H-2B program reached its high point of 129,547 in fiscal year 2007.53 It should be noted that because of extensions and exemptions from the cap, the actual number of H-2B workers was likely higher in 2007, but the true number is unknown because those data on visa extensions are not publicly available.

New data from the USCIS H-2B Employer Data Hub that were first published in 2021 provide new insights into the current size of the H-2B program and the impact of the returning worker and supplemental H-2B visas that have been added since fiscal year 2016.

Previously, similar to H-2A, the best available information on the size of the H-2B program came from disclosure data on labor certifications, which are published by the Department of Labor (DOL), and the number of visas issued, which is published by the State Department. Labor certifications, however, do not consider the H-2B cap—in other words, DOL will continue to approve them even if the H-2B cap has been reached. Therefore these certifications show only the number of H-2B jobs that have been certified by DOL to be filled with H-2B workers, not the actual number of H-2B workers who are ultimately employed. Once DOL has certified the jobs employers wish to fill, the employers must then petition USCIS for H-2B workers. Before USCIS approves an H-2B petition, it must consider whether the H-2B job and petition fall under the annual cap. The result of this process is that every year there are many more labor certifications from DOL than there are petitions that are ultimately approved by USCIS allowing employers to hire H-2B workers.

The State Department’s publication of the number of visas issued is another important data source, but these data do not account for H-2B workers who had their visas extended and remained in the United States beyond the initial fiscal year for which they were approved, or for H-2B workers who may have switched into H-2B from another status. For these reasons, the State Department data are also an imperfect source for measuring the number of H-2B workers.

Data from the USCIS H-2B Employer Data Hub, on the other hand, since it represents individual jobs that USCIS has approved to be filled with H-2B workers, and includes data on visa extensions, is the best available tool for measuring the total number of workers employed in H-2B status. However, as noted in the box on data above, there are caveats.

For one, the number of approvals in the USCIS H-2B data may overcount the number of individual H-2B workers. That’s because in cases in which a worker was changing jobs or changing job conditions with the same employer, that individual may appear twice in the database; however USCIS does not identify when an approval is for an H-2B worker changing jobs or job conditions.

In addition, there is not a direct correspondence between the number of H-2B petitions and the number of H-2B workers ultimately employed because visas for workers with approved USCIS petitions may be denied at the consular level by the State Department. In my estimate on the number of H-2B workers I account for this by subtracting the number of H-2B visas denied by the State Department from the number of petitions approved by USCIS for new employment.

USCIS H-2B Data Hub data are available only going back to 2015—the year immediately before Congress first expanded the H-2B program through an appropriations rider—but those data at least permit us to see what the baseline number of H-2B workers employed was before the expansions via supplemental visas. Figure D shows that in 2015, while the statutory cap of 66,000 was still in place—the total number of H-2B workers approved by USCIS was 85,793, of which 79,603 were new approvals and 6,190 were visa extensions. A total of 9,188 H-2B visa applications were denied by the State Department at the consular stage. After subtracting visa denials, the total estimated number of H-2B workers in 2015 is 76,605.

The H-2B visa program is nearly double the size of the original annual cap and set to grow larger: H-2B workers employed in the United States according to approved USCIS petitions and visas issued by the State Department, FY 2015–21, and projected H-2B workers in 2022

| Year | New H-2B workers | H-2B extensions | New visas issued | New visas issued | H-2B statutory cap | H-2B cap + supplemental cap | H-2B cap + supplemental cap |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 70,415 | 6,190 | 69,684 | 66,000 | |||

| 2016 | 87,114 | 5,237 | 84,627 | 66,000 | |||

| 2017 | 84,241 | 7,352 | 83,600 | 66,000 | 81,000 | ||

| 2018 | 83,206 | 9,773 | 83,774 | 66,000 | 81,000 | ||

| 2019 | 106,151 | 11,359 | 97,623 | 66,000 | 96,000 | ||

| 2020 | 73,131 | 15,719 | 61,865 | 66,000 | |||

| 2021 | 106,635 | 19,555 | 95,053 | 95,053 | 66,000 | 88,000 | |

| 2022 | 125,754 | 19,555 | 125,754 | 66,000 | 121,000 |

Note: "New H-2B workers" column represents USCIS petitions for H-2B workers approved for new employment, minus the number of visas denied for H-2B workers in the same fiscal year (see text). "H-2B visa extensions" represents USCIS petitions for H-2B workers approved for continuing employment (i.e. visa extensions). The line labeled "New visas issued" represents the number of H-2B visas issued by the State Department in the corresponding fiscal year. The "H-2B statutory cap" is set in law at 66,000 new H-2B visas per year. The line labeled "H-2B cap + supplemental cap" is the number of H-2B visas authorized in the statutory cap plus the number of supplemental visas authorized by Congress and the executive branch for the corresponding fiscal year. The column labeled "Projected" are totals that have been projected for fiscal year 2022 (see text).

Source: EPI analysis of United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, H-2B Employer Data Hub, fiscal year 2015-2021 data files, and U.S. Department of State, "Nonimmigrant Visa Statistics" [see PDF files for tables listed under "Nonimmigrant Worldwide Issuance and Refusal Data by Visa Category" and "Nonimmigrant Visas by Individual Class of Admission" for fiscal years 2015-2021].

In 2021, when 22,000 supplemental H-2B visas were added to the statutory cap of 66,000, for a total cap of 88,000, USCIS approved a total of 132,101 petitions for H-2B workers. The 132,101 H-2B workers included 112,546 new H-2B workers and 19,555 visa extensions. However 5,911 visas were denied in 2021. After subtracting denied visas, the total number of H-2B workers for 2021 was 126,190. The 2021 total was nearly double the size of the annual cap and came close to the record high of 129,547 from 2007.

It must also be noted that there are some discrepancies in the H-2B data reported by USCIS that have not been explained by the agency. For example, while the data in the 2021 USCIS H-2B Employer Data Hub show there were 132,101 total approvals for H-2B workers, the USCIS Characteristics of H-2B Nonagricultural Temporary Workersreport shows that there were 134,654 total H-2B petitions approved.54 The number of new approved workers in 2021, at 112,546, is much higher than the annual cap plus the number of permitted supplemental visas for 2021, which totaled 88,000. There were only 10,665 approvals in the Data Hub data for new H-2B workers that were exempt from the cap in 2021, a number much lower than the 24,546 difference between the authorized 88,000 visas and the 112,546 petitions approved for 2021. One possibility is that the difference is made up of H-2B workers with petition approvals to change employers or change job conditions. However, the USCIS data are not detailed enough to allow us to discern between the different types of approvals and USCIS has not reported or suggested anywhere that this is the case. All of this raises the question of whether USCIS is approving more H-2B petitions than allowed by law.

The size of the H-2B program is projected to reach a new high in 2022

The number of H-2B workers is set to grow higher still in fiscal year 2022. As discussed above, the Biden administration has added 55,000 supplemental H-2B visas to the 66,000 annual cap, setting the total limit for the year at 121,000. The last bar in Figure D (labeled “Projected”) shows an estimate of the number of H-2B workers for 2022. I construct the 2022 estimate as follows: First, I take the number of H-2B workers in the cap set by the Biden administration of 121,000 for 2022. I then add 10,665 additional workers, using the number of new H-2B workers from 2021 that were exempt from the annual cap, according to the USCIS H-2B Employer Data Hub. Then I subtract from that total 5,911, the number of visas that were denied by the State Department in 2021. Finally, I add the number of visa extensions from 2021 (19,555). The final result is a projected total of 145,301 H-2B workers for 2022, a new record high and more than double the original statutory annual cap.55

The H-2A and H-2B visa programs: Wage and hour enforcement statistics show that workers are vulnerable in the workplace

Why does it matter that the H-2A and H-2B programs have grown in recent years? Because while the H-2A and H-2B programs continue to expand—with further growth expected, and the Biden administration making H-2 programs a central component of their Collaborative Migration Management Strategy for Central and North America—at the same time, data on labor standards enforcement from the Wage and Hour Division make clear that farmworkers in agriculture, including H-2A workers, and all workers in H-2B industries are not adequately protected in the workplace. As the program expansions continue, much more must be done to ensure that both temporary migrant workers and U.S. workers are paid and treated fairly. This section discusses some of the available data on wage and hour enforcement in H-2A and H-2B industries.

Inadequate labor standards enforcement in agriculture leaves all farmworkers vulnerable to wage theft and other violations

Farmworkers in the United States earn some of the lowest wages in the labor market and experience an above-average rate of workplace injuries.56 In addition, a large share of them are also vulnerable to exploitation and abuse in the workplace because of their immigration status.

The U.S. Department of Labor’s National Agricultural Workers Survey reports that 44% of the non-H-2A crop workers were unauthorized immigrants in 2019–2020,57 and as discussed above there were just over 300,000 H-2A workers employed in the United States in 2021, who worked for an average of six months out of the year, representing roughly 10% to 15% of farmworkers employed on U.S. crop farms. Both unauthorized and H-2A workers have limited labor rights and are vulnerable to wage theft and other abuses due to their immigration status.58 The remaining farm workforce, roughly half of all farmworkers, are U.S. citizens and legal immigrants with full rights and agency in the labor market. But that means that roughly half of all farmworkers are vulnerable to violations of their rights because of their lack of an immigration status or their precarious, temporary immigration status.

The U.S. Department of Labor’s (DOL) Wage and Hour Division (WHD) is the federal agency that protects the rights of farmworkers in terms of wage and hour laws, including those that protect H-2A workers. WHD labor standards enforcement actions are intended to ensure that the rights of workers are protected, and to level the playing field for employers, so that employers that underpay workers or engage in other cost-reducing behavior in violation of wage and hour laws do not gain a competitive advantage over law-abiding employers. WHD aims to “promote and achieve compliance with labor standards to protect and enhance the welfare of the nation’s workforce” by enforcing 13 federal labor standards laws, including the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), which requires minimum wages and overtime pay, and regulates the employment of workers who are younger than 18, as well as the Family and Medical Leave Act, and laws governing government contracts, consumer credit, and the use of polygraph testing, etc.59 WHD also enforces two laws and their implementing regulations specific to agricultural employment. One is the Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act (MSPA), the major federal law that protects U.S. farmworkers. The other is the statute that establishes the H-2A program.

In December 2020, Dr. Philip Martin, Dr. Zach Rutledge, and I published a lengthy report analyzing 20-years of data from WHD on their enforcement actions in agriculture.60 The rest of this section highlights some of the key findings and updates some of the data findings.

First, it is important to note that the number of WHD investigations in agriculture has declined sharply since the year 2000. Figure E shows a clear downward trend in the number of WHD investigations at agricultural worksites over the past two decades, from more than 2,000 a year in the early 2000s to just 1,000 in fiscal year 2021.

Wage and Hour Division investigations of agricultural employers, fiscal years 2000–2021

| Fiscal Year | Inspections of agricultural employers |

|---|---|

| 2000 | 2,431 |

| 2001 | 2,300 |

| 2002 | 2,176 |

| 2003 | 1,495 |

| 2004 | 1,630 |

| 2005 | 1,449 |

| 2006 | 1,410 |

| 2007 | 1,666 |

| 2008 | 1,600 |

| 2009 | 1,377 |

| 2010 | 1,277 |

| 2011 | 1,527 |

| 2012 | 1,659 |

| 2013 | 1,673 |

| 2014 | 1,430 |

| 2015 | 1,361 |

| 2016 | 1,275 |

| 2017 | 1,307 |

| 2018 | 1,076 |

| 2019 | 1,125 |

| 2020 | 1,036 |

| 2021 | 1,000 |

Source: Authors’ analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, Agriculture data table.

What explains fewer investigations of farm employers? While labor enforcement priorities vary by administration, funding for WHD has lagged behind the growth of the U.S. labor force. In inflation-adjusted dollars, WHD’s budget in 2020 was $13 million less than it was in 2012.61 Figure F shows that in 2021 there were only 782 WHD investigators enforcing federal labor standards, 30 fewer than in 1973. Hamaji et al. note that in 1978, there was one WHD investigator for every 69,000 U.S. workers; by 2018, there was one investigator for every 175,000 U.S. workers.62 And as noted earlier, funding for DOL’s WHD and OSHA has remained flat over the past decade, while the number of workers they are responsible for protecting has increased sharply.63

Number of Wage and Hour Division investigators, U.S. Department of Labor, 1973–2021

| Year | Investigators on board at years’ end |

|---|---|

| 1973 | 812 |

| 1974 | 869 |

| 1975 | 921 |

| 1976 | 964 |

| 1977 | 980 |

| 1978 | 1,232 |

| 1979 | 1,087 |

| 1980 | 1,059 |

| 1981 | 953 |

| 1982 | 914 |

| 1983 | 928 |

| 1984 | 916 |

| 1985 | 950 |

| 1986 | 908 |

| 1987 | 951 |

| 1988 | 952 |

| 1989 | 970 |

| 1990 | 938 |

| 1991 | 865 |

| 1992 | 835 |

| 1993 | 804 |

| 1994 | 800 |

| 1995 | 809 |

| 1996 | 781 |

| 1997 | 942 |

| 1998 | 942 |

| 1999 | 938 |

| 2000 | 949 |

| 2001 | 945 |

| 2002 | 898 |

| 2003 | 850 |

| 2004 | 788 |

| 2005 | 773 |

| 2006 | 751 |

| 2007 | 732 |

| 2008 | 731 |

| 2009 | 894 |

| 2010 | 1,035 |

| 2011 | 1,024 |

| 2012 | 1,067 |

| 2013 | 1,040 |

| 2014 | 976 |

| 2015 | 995 |

| 2016 | 974 |

| 2017 | 912 |

| 2018 | 835 |

| 2019 | 780 |

| 2020 | 823 |

| 2021 | 782 |

Note: Numbers represent Wage and Hour Division investigators on staff at the end of each year.

Source: Authors' analysis of Wage and Hour Division data on the number of investigators; from unpublished Excel files provided by WHD staff members to the author. For 2020 and 2021, source is Rebecca Rainey, "Wage-Hour Investigator Hiring Plans Signal DOL Enforcement Drive," Bloomberg Law, January 28, 2022.

Nonetheless, Figure G shows that despite fewer investigations and WHD investigators, the total back wages owed for all violations of federal wage and hour laws in agriculture has been on a generally upward trend, peaking at $8.4 million in FY2013 (in constant 2019 dollars), the same year that civil money penalty assessments peaked at $8.0 million. Annual back wages and CMPs were between $3.8 million and $6.7 million between 2015 and 2019 (in 2019 dollars). The latest data released by WHD shows that in 2021, with 1,000 investigations in agriculture, 10,379 workers were assessed to be owed back wages, with a total of $8.4 million total owed back wages for agricultural workers (in 2021 dollars) and over $7.4 million assessed to agricultural employers in civil money penalties.64

Back wages and civil money penalties assessed (in millions of dollars) against agricultural employers by the Wage and Hour Division, fiscal years 2000–2019

| Fiscal year | Back wages | Civil money penalties |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | $1.98 | $2.04 |

| 2001 | 2.50 | 1.83 |

| 2002 | 2.89 | 1.69 |

| 2003 | 3.40 | 1.58 |

| 2004 | 1.65 | 2.24 |

| 2005 | 1.75 | 1.40 |

| 2006 | 2.15 | 1.03 |

| 2007 | 3.94 | 1.79 |

| 2008 | 2.52 | 1.60 |

| 2009 | 1.68 | 1.50 |

| 2010 | 3.71 | 1.30 |

| 2011 | 3.25 | 2.21 |

| 2012 | 5.88 | 5.10 |

| 2013 | 8.45 | 8.02 |

| 2014 | 4.87 | 3.35 |

| 2015 | 4.66 | 5.46 |

| 2016 | 5.16 | 3.77 |

| 2017 | 5.26 | 4.53 |

| 2018 | 4.28 | 6.66 |

| 2019 | 6.06 | 6.33 |

Note: Data are inflation adjusted to 2019 dollars.

Source: Authors’ analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, Agriculture data table (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020a).

In addition, despite fewer investigations, it is the case that when WHD initiates an investigation of an agricultural employer, they often find violations. Figure H groups the number of violations found per investigation during the FY2005–FY2019 period, from zero to more than five violations per investigation. When looked at this way, the data reveal a U-shape among the violators, with almost 30% of investigations bunched at the zero and 31% bunched at more than five violations; those two ends of the spectrum account for almost two-thirds of the violations, while 17% of investigations found one violation and 23%, nearly a quarter, found two to four violations. However, overall, the data show that 70% of all investigations detected violations, while 30% detected zero violations. In addition, it should be noted that this figure does not account for the severity of the violations or the amounts assessed. In other words, some investigations that detected one or two violations may have detected egregious violations and found employers owing large amounts of back pay, while investigations that detected with five or more violations may have resulted in smaller amounts of back wages owed.

Over 70% of federal investigations of agricultural employers detected wage and hour violations: Violations detected during investigations of agricultural employers, by number of violations found per investigation, fiscal years 2005–2019

| Number of violations | Share of investigations |

|---|---|

| 0 violations | 29.5% |

| 1 violation | 16.7% |

| 2–4 violations | 22.7% |

| 5+ violations | 31.1% |

Note: Data include H-2A, MSPA, FLSA, and all other types of employment law violations in the agricultural sector.

Source: Authors' analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Compliance Action Data (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f).

One particular area of interest to highlight with respect to wage and hour enforcement in agriculture is the employment of farmworkers by farm labor contractors (FLCs). FLCs are nonfarm employers that act as staffing firms for farm employers. For FLCs, which correspond to NAICS code 115115, average employment was 181,000 in 2019, according to the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages from DOL; FLCs are a subset of the Support Activities for Crop Production category (NAICS 1151), which had average employment of 342,000 in 2019, meaning that FLCs accounted for 53% of U.S. crop support services employment.

FLCs accounted for 14% of total average employment in UI-covered agriculture of 1.3 million in 2019—including employment in both crops and animal agriculture—but accounted for one-quarter of all wage and hour law violations detected in agriculture (24%). Thus, the share of agricultural employment law violations committed by farm labor contractors was 10 percentage points greater than the FLC share of average annual agricultural employment. In practical terms, that means that farmworkers employed by FLCs or on farms that use FLCs are more likely to suffer wage and hour violations than farmworkers who are employed by farms directly.

We also found that 75% of all WHD investigations of FLCs detected violations, while 25% of investigations detected zero violations. We grouped the number of violations detected per investigation of FLCs, as shown in Figure I. The share of investigations of FLCs that found zero violations, at 25%, was significantly less than the share of investigations of FLCs that found five or more violations, 36%. Nearly two-fifths of investigations detected either one violation or two to four violations.

Three-fourths of federal investigations of farm labor contractors detected wage and hour violations: Violations detected during investigations of farm labor contractors, by number of violations found per investigation, fiscal years 2005–2019

| Number of violations | Share of investigations |

|---|---|

| 0 Violations | 25.3% |

| 1 Violation | 15.9% |

| 2–4 Violations | 22.9% |

| 5+ Violations | 35.9% |

Source: Authors' analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Compliance Action Data (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f).

We also reviewed violations by FLCs in the two major agricultural states of California and Florida. California and Florida each accounted for 14% of the wage and hour violations detected as the result of WHD investigations nationwide, by far the most, followed by North Carolina with 10%, Texas and Washington with 5% each, and Oregon with 4%. These six states accounted for 52% of all employment law violations found in agriculture. In the two states with the highest shares of violations, California and Florida, FLCs accounted for the largest share of the violations detected by WHD investigators. Figure J shows that FLCs accounted for 48% of the total violations in California during fiscal years 2005 to 2019, and Figure K shows that FLCs accounted for 50% of the total violations detected in Florida over the same period. This finding is particularly significant for California, given that FLCs now account for a majority of crop employment in the state.65

Employment law violations detected in California by the Wage and Hour Division among all agricultural employers and farm labor contractors, fiscal years 2005–2019

| Year | Violations by all agricultural employers | Violations by farm labor contractors |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 1,233 | 972 |

| 2006 | 4,166 | 918 |

| 2007 | 1,931 | 1,189 |

| 2008 | 2,911 | 1,469 |

| 2009 | 2,202 | 1,645 |

| 2010 | 1,577 | 363 |

| 2011 | 2,909 | 1,949 |

| 2012 | 4,589 | 1,556 |

| 2013 | 5,420 | 3,348 |

| 2014 | 3,079 | 1,302 |

| 2015 | 2,181 | 947 |

| 2016 | 2,113 | 1,490 |

| 2017 | 1,902 | 570 |

| 2018 | 2,794 | 733 |

| 2019 | 315 | 240 |

Note: Violations by California farm labor contractor are a subset of employment law violations detected among all agricultural employers in California.

Source: Authors' analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Compliance Action Data (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f).

Employment law violations detected in Florida by the Wage and Hour Division among all agricultural employers and farm labor contractors, fiscal years 2005–2019

| Year | Violations by all agricultural employers | Violations by farm labor contractors |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 1,225 | 670 |

| 2006 | 1,484 | 686 |

| 2007 | 4,469 | 1,643 |

| 2008 | 1,989 | 1,021 |

| 2009 | 2,034 | 1,020 |

| 2010 | 2,886 | 545 |

| 2011 | 4,045 | 1,726 |

| 2012 | 4,633 | 2,765 |

| 2013 | 2,380 | 1,084 |

| 2014 | 3,744 | 1,986 |

| 2015 | 3,338 | 2,360 |

| 2016 | 1,871 | 1,182 |

| 2017 | 1,837 | 974 |

| 2018 | 1,412 | 1,112 |

| 2019 | 989 | 455 |

Note: Violations by Florida farm labor contractor are a subset of employment law violations detected among all agricultural employers in Florida..

Source: Authors' analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Compliance Action Data (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f).

To conclude, it is within this context H-2A workers are employed; where there are fewer investigations and fewer WHD investigators policing the farm labor market, where thousands of workers are robbed by farm employers every year, and where farm labor contractors with a fissured business model are proliferating. As a result, much more must be done to protect H-2A workers in the workplace, given that they are vulnerable due not just to the industry in which they are employed, but also because their precarious immigration status makes it difficult for them to complain when they are victimized by employers, recruiters, and FLCs.

Wage theft is a massive problem in the major H-2B industries: Employers stole $1.8 billion from workers since 2000

The data discussed in the previous section are clear that the H-2B program’s size is on the cusp of reaching new heights. Why does that matter? Because at the same time, data on labor standards enforcement from DOL’s WHD paint a picture of rampant wage theft and lawbreaking by employers in the industries that employ most H-2B workers. H-2B workers are being recruited into industries where they will be vulnerable, but no new measures have been implemented yet by the Biden administration to better protect them.

WHD publishes and annually updates tables with summary data on the outcomes of WHD enforcement actions in what it calls “industries with high prevalence of H-2B workers.” The seven industries that WHD lists in these data tables include landscaping services, janitorial services, hotels and motels, forestry, food services, construction, and amusement. Data on the top H-2B occupations (from DOL labor certifications and from the USCIS H-2B Employer Data Hub) show that the vast majority of H-2B jobs that are certified by DOL and approved by USCIS are within these broad industries.66

Table 2 lists the top H-2B occupations by number of approvals in the USCIS H-2B Employer Data Hub. The listed occupations generally correspond with the seven “high H-2B prevalence” industries listed by WHD in their data tables and accounted for 99.1% of all H-2B approvals in 2021. If we exclude occupation #8, “N/A”—which represents data observations in which the occupation field was missing—the remaining nine occupations still account for 95.7% of all H-2B approvals in 2021.67

Nearly all H-2B workers are employed in a small number of occupations: Top 10 H-2B occupations by number of USCIS-approved petitions, fiscal year 2021

| H-2B Rank | Major group SOC code | Occupation | Initial approval | Continuing approval | Total approvals | Share of total H-2B approvals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 37 | Building and Grounds Cleaning and Maintenance Occupations | 56,388 | 6,960 | 63,348 | 48.0% |

| 2 | 51 | Production Occupations | 13,087 | 2,674 | 15,761 | 11.9% |

| 3 | 45 | Farming, Fishing, and Forestry Occupations | 10,692 | 2,057 | 12,749 | 9.7% |

| 4 | 35 | Food Preparation and Serving Related Occupations | 6,744 | 3,262 | 10,006 | 7.6% |

| 5 | 39 | Personal Care and Service Occupations | 8,785 | 1,149 | 9,934 | 7.5% |

| 6 | 47 | Construction and Extraction Occupations | 7,270 | 1,052 | 8,322 | 6.3% |

| 7 | 53 | Transportation and Material-Moving Occupations | 4,512 | 576 | 5,088 | 3.9% |

| 8 | N/A | N/A | 3,191 | 1,424 | 4,615 | 3.5% |

| 9 | 49 | Installation, Maintenance, and Repair Occupations | 512 | 101 | 613 | 0.5% |

| 10 | 27 | Arts, Design, Entertainment, Sports, and Media Occupations | 520 | 22 | 542 | 0.4% |

| Totals for the top 10 | 111,701 | 19,277 | 130,978 | 99.1% | ||

| Totals for top 10 occupations excluding N/A | 108,510 | 17,853 | 126,363 | 95.7% | ||

| Total H-2B approvals, all occupations | 112,546 | 19,555 | 132,101 | 100% | ||

Note: SOC stands for Standard Occupational Classification, which is a system of job classification created by the U.S. Department of Labor, see https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_stru.htm#47-0000

Source: United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, H-2B Employer Data Hub, fiscal year 2021 data file.

The published WHD enforcement data include tables for individual fiscal years in four different categories.68 The first set of tables, “All Acts,” includes data on violations of all wage and hour laws enforced by WHD in the listed industries. The second set of tables, “H-2B,” summarizes employer violations of H-2B program laws and regulations. The next set, “FLSA,” summarizes employer violations of the Fair Labor Standards Act. The final set, “All Others,” summarizes violations of all laws that WHD enforces except for violations of FLSA or H-2B laws and regulations.

In the “All Acts” tables, the data fields listed by WHD in their enforcement data for the seven selected industries include:

- Cases: the number of cases investigated by WHD

- Cases with violation: the number of cases in which violations of the law were found

- EEs (employees) employed in violation: the number of employees involved in the cases in which violations were found