What this report finds: Thousands of skilled migrants with H-1B visas working as subcontractors at well-known corporations like Disney, FedEx, Google, and others appear to have been underpaid by at least $95 million. Victims include not only the H-1B workers but also the U.S. workers who are either displaced or whose wages and working conditions degrade when employers are allowed to underpay skilled migrant workers with impunity. The workers in question were employed by HCL Technologies, an India-based IT staffing firm that earned $11 billion in revenue last year. HCL profits by placing workers on temporary H-1B work visas at many top companies. The H-1B statute requires that employers pay their H-1B workers no less than the actual wage paid to their similarly employed U.S. workers. But EPI analysis of an internal HCL document, released as part of a whistleblower lawsuit against the firm, shows that large-scale illegal underpayment of H-1B workers is a core part of the firm’s competitive strategy.

Why it matters: This apparent blatant lawbreaking by one of the leading H-1B outsourcing companies should finally prompt action by the federal government to curb abuses of the H-1B program. Such abuses are likely widespread among H-1B employers because the Department of Labor (DOL) has done virtually nothing to ensure program integrity by enforcing the wage rules. More broadly, DOL props up the abusive outsourcing business model by treating contractor hires differently than direct hires when enforcing the wage and other provisions in the H-1B statute that are supposed to protect H-1B and U.S. workers. This outsourcing loophole allows firms like HCL and the big tech companies that use outsourcing firms to get around those provisions. Thanks to its failure to enforce the wage laws or close the outsourcing loophole, DOL is in effect subsidizing the offshoring of high-paying U.S. jobs in information technology that once served as a pathway to the middle class, including for workers of color.

What we can do about it: The Department of Labor should launch a sweeping investigation into whether companies are systematically underpaying H-1B workers in violation of the law. If violations are found, penalties should be imposed that are significant enough to deter all H-1B employers from such behavior. DOL should also close the outsourcing loophole that supports the outsourcing business model by requiring both direct employers like HCL and the secondary employers that use H-1B staffing firms to attest that they will comply with H-1B wage rules. DOL and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) should take additional measures to ensure the H-1B program achieves its purpose of filling genuine labor market gaps. Such measures include raising minimum wages to realistic market levels, allocating H-1B visas to workers with the highest skills and wages, and adopting a compliance system that ensures program accountability and integrity. Finally, the Department of Justice’s (DOJ) Civil Division, in conjunction with DOL and DHS, should vigorously prosecute visa fraud under the False Claims Act, consistent with a recent federal court decision applying the False Claims Act to H-1B visa fraud.

Introduction and key findings: New data on H-1B abuse and why it matters

For nearly a decade and a half, news reports, research, investigations, and congressional hearings have detailed the abuses of the H-1B visa program by some of the biggest information technology companies.1 The H-1B program is a temporary work visa program that allows U.S. companies to recruit and hire college-educated migrant workers. It is one of the few work visa programs that can provide temporary migrant workers with the possibility of a path to permanent residency and citizenship, although that path is controlled by and at the discretion of H-1B employers. The original intent of the program was to attract skilled and talented workers to the United States to fill labor shortages in professional fields.2

Since the creation of the program, the abuses of the program have been many, included vastly underpaying workers, laying off U.S. workers and replacing them with much lower-paid H-1B workers, forcing U.S. workers to train their H-1B replacements as a condition of receiving severance and unemployment insurance, and cheating the H-1B lottery to acquire additional visas. There are provisions in the H-1B law that are supposed to work together to prevent employers from underpaying H-1B workers or replacing their incumbent U.S. worker employees (i.e., U.S. citizens or permanent residents) with H-1B workers who are paid much less to do the same job. But employers are getting around those provisions by contracting with IT outsourcing firms, enabled by the U.S Department of Labor’s (DOL) flawed interpretation that puts outsourced H-1B workers in a different comparison pool than U.S. workers who are hired directly by the employer (see text box, ”How companies contract with H-1B outsourcing firms to evade H-1B visa rules that protect wages and working conditions,” later in the report). As a result, clear abuses that contradict the original intention of the H-1B program have largely not turned into what DOL considers actionable violations leading to sanctions.

One widely reported example from the last decade illustrates the issue. The IT outsourcing firms Infosys and Tata Consultancy Services contracted with Southern California Edison (SCE), an energy provider, to replace hundreds of SCE employees with H-1B workers who were paid less to do the same jobs, with the U.S. workers being required to first train their H-1B replacements.3 When filing an H-1B application, one of the things that employers must attest to is that the filings do not adversely impact the wages and working conditions of similarly employed U.S. workers. But DOL investigated the case and found no wrongdoing: The outsourcing firms were the ones who had to attest to meeting certain provisions in the visa applications, and the SCE workers who were replaced were not considered part of the “similarly employed U.S. workers” whose wages and working conditions the outsourcing firms had to vouch not to adversely impact.4

In sum, DOL has determined it is acceptable for an employer to underpay an H-1B worker, even if U.S. workers are obviously being harmed, as long as the H-1B worker is hired through a contractor. This seemingly irrational DOL interpretation is the main reason why the dozens of news reports chronicling thousands of U.S. workers training their H-1B replacements—at Disney, the University of California, New York Life, Mass Mutual, Southern California Edison, etc.—have never resulted in a single penalty or any change in business behavior. In every reported case, the lower-paid H-1B worker was hired and employed by an outsourcing firm.

There have been calls to close the outsourcing loophole but thus far the Department of Labor has not committed to doing so. In fact the department issued and then abandoned policy guidance that would have closed the loophole (as discussed later on in the report).

Now thanks to a federal whistleblower lawsuit brought against outsourcing firm HCL Technologies (HCL),5 we don’t need to wait for DOL to close the outsourcing loophole to achieve some justice for the workers affected by abuses of the H-1B program. As a result of the lawsuit, we have new insights into what appear to be clear violations of another element of the H-1B statute, one which requires employers to pay their H-1B employees no less than they pay their U.S. employees who are citizens or permanent residents (referred to in this report as “U.S. workers”). These violations call for immediate federal action. In this case, the alleged violations cannot be waved off via the outsourcing loophole because HCL itself appears to be paying its own H-1B employees less than it pays its own U.S. worker employees.

HCL, India’s third-largest IT outsourcing firm, is a familiar name in the tech world. It earned notoriety about six years ago when Disney made headlines for forcing its workers to train their replacements who were migrant guestworkers employed through the H-1B visa program (and supplied to Disney by HCL). HCL is now the defendant in a lawsuit brought under the False Claims Act for the firm’s alleged “egregious and widespread fraud against the United States in applying for and securing visas.”6 The most significant of the alleged violations is rampant wage theft by HCL via paying H-1B workers less than they are statutorily required to be paid, estimated in this report to likely exceed $95 million annually. A document related to the case that recently became public exposes details that show how underpaying H-1B workers is an intentional corporate strategy.

Specifically, an internal HCL presentation of its strategy for filing H-1B visa applications7 shows how it hires migrant workers employed through work visas to fill jobs in key business lines and job roles to maximize wage savings compared with hiring U.S. citizens and permanent residents. This strategy document provides details on the wages paid to HCL employees in the United States on H-1B visas and HCL employees who are U.S. citizens and permanent residents. Wages of the former are far lower than wages of the latter.

The HCL document is significant beyond the case itself because most of the biggest users of H-1B visas are companies that have outsourcing business models like HCL’s.8 And the jobs that these companies are outsourcing—in IT services and software development—are the relatively high-wage but entry- to mid-level technology jobs that for years served as a bridge to the American middle class.9 Some of these IT jobs are especially important to women and workers of color. For example, computer systems analyst is one of the few IT occupations with a reasonable share of women employed, and African Americans are better represented in this occupation than in other major computer occupations.10

The document is our first inside look at an outsourcing firm’s playbook for abusing work visa programs—abuse that appears to not comport with either the letter or intent of the law. It also raises serious questions about efforts by the U.S. Department of Labor to enforce the sections of the H-1B statute and regulations intended to protect the wages and working conditions of both U.S. workers and migrant workers. These revelations serve as a compelling justification for a sweeping investigation by DOL into whether companies are systematically underpaying H-1B workers in violation of the law, and for immediate action by Congress and the Biden administration to protect labor standards.

Key findings

Following are key takeaways from the report:

- The IT outsourcing firm at the center of the whistleblower case alleging fraud of the H-1B temporary work visa program is one of the largest H-1B employers. A lawsuit brought under the False Claims Act alleges that that HCL Technologies (HCL) committed fraud when acquiring H-1B visas, which are visas for highly skilled workers. HCL earned nearly $7 billion from its U.S. operations in 2020, ranked eighth in total H-1B approvals with more than 4,000 in 2020, and has received more than 31,000 visas since 2009. It is India’s third-largest IT outsourcing firm, earning 63% of its $11 billion in revenue in 2020 from the United States. It maximizes profit by finding H-1B workers who are significantly less expensive to employ than already-employed U.S. workers.

- According to an internal document from HCL, the firm appears to craft its H-1B workforce composition based on job roles where it can save the most on labor costs compared with what it pays U.S. employees for the same position. One of HCL’s internal corporate documents—a presentation containing details about HCL’s corporate strategy, as well as detailed information about the composition of HCL’s workforce, disaggregated by immigration status, occupation, and salary—was made public in the lawsuit. HCL’s actions are inconsistent with what the H-1B law explicitly requires, and also violates the spirit of the law, which is intended to protect wages and labor standards for both migrant workers and U.S. workers.

- HCL pays its H-1B workers less than the U.S. workers it employs with similar skills as a key competitive strategy, allowing it to expand its business and increase profits. The data from the company’s internal document suggest the firm underpays H-1B workers in virtually all jobs across all business lines.

- HCL itself disclosed its apparent underpayments to H-1B employees, underpayments which would violate the requirement that employers pay their H-1B employees no less than they pay their U.S. worker employees. According to HCL’s own calculations in its internal document, the firm systematically pays H-1B workers much less than its U.S. citizen employees, contravening HCL’s attestations in its visa applications to the U.S. Department of Labor that it will pay H-1B workers the higher of the prevailing wage (in layman’s terms, what most workers engaged in similar work in the same geographic area earn according to a DOL methodology) or the “actual wage” paid to its employees who are U.S. citizens or lawful permanent residents and doing the same work at the company.

- HCL’s apparent wage theft from H-1B workers amounts to approximately $95 million annually, according to our estimate based on information revealed in the presentation.

- The HCL document reveals clear violations of the H-1B statute that the U.S. government has failed to enforce. Much attention has been paid to the legal ways that employers underpay their H-1B workers—by opting (with no government oversight) to comply with the prevailing wage requirement by paying entry- and junior-level prevailing wages that are actually much lower than what workers of similar education and experience elsewhere are actually paid. While those prevailing wage levels should be raised, the DOL should also focus on the other part of the “wage requirement” section of the H-1B law that requires employers to pay their H-1B workers at least the same actual wage as their similarly employed U.S. workers. We have not found evidence that DOL has ever investigated or enforced this rule for any firm.

- HCL’s actions are tantamount to U.S. immigration policy being used to subsidize the outsourcing and offshoring of decent, high-paying U.S. jobs. Allowing employers to pay their H-1B workers less than the market rate for their labor—both legally through the flawed prevailing wage rule and unlawfully due to a lack of enforcement of the actual wage rule—in tandem with DOL’s flawed interpretation of the law, DOL has made the H-1B the “outsourcing visa.” In other words this interpretation is accelerating the fissuring—the outsourcing of jobs to lower-paid contract workers that degrades wages and job quality more broadly—of the IT labor market and its destructive effects.

- The abuse revealed by the HCL presentation is the proverbial tip of the iceberg: it points to widespread, systemic H-1B abuse. HCL did not invent nor pioneer the exploitation of H-1B program; its exploitation of the H-1B program is standard industry practice, not an outlier.

- Fourteen years ago, Sens. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) and Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) revealed for the first time that outsourcing firms, like HCL, were the biggest users of the H-1B program. Outsourcing firms have consistently dominated the program since then. Outsourcing firms mimic one another’s business practices, including techniques to exploit the H-1B program.

- The top seven H-1B employers in fiscal year 2015—the year the HCL document reflects—were outsourcing firms and direct competitors of HCL. They all pay their H-1B workers at wage rates that are similar or lower than what HCL pays, and all the outsourcing firms paid relatively lower wages than what the biggest H-1B employers that directly employed their H-1B workers paid in that year.

- Congress and the Biden administration should take immediate action to fix the H-1B program’s flaws.

- The relevant federal agencies, including the Departments of Labor, Homeland Security, and Justice, should launch investigations into H-1B wage theft.

- The Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division (WHD) and Employment and Training Administration (ETA) should require and conduct better and effective oversight going forward and seek to raise prevailing wage standards in the H-1B program via regulation, and the Department of Homeland Security’s United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), should also conduct better oversight and improve the visa allocation process in the H-1B program, also via regulation.

- The Department of Justice’s (DOJ) Civil Division, in conjunction with USCIS and DOL, should vigorously prosecute visa fraud under the False Claims Act, consistent with a recent federal court decision applying the False Claims Act to H-1B visa fraud.

- Congress should act by passing lasting legislative reforms to fix the H-1B program and stem abuses, and to increase protections for both H-1B workers and U.S. workers.

H-1B wage requirement: Intended to protect both H-1B and U.S. workers

The H-1B visa program is the largest U.S. temporary work visa program for high-skilled workers, with approximately 600,000 visa holders currently in the United States.11 The H-1B visa authorizes firms to employ foreign college-educated workers under specific conditions. Because these “guestworker” visas are highly vulnerable to abuse—often because the visa application and status is controlled by employers, which restricts labor market mobility for migrant workers—Congress included provisions in the visa’s requirements to protect wages and labor standards for both U.S. workers and migrant workers on H-1B visas. The principal protection is the wage requirement—which is intended to ensure that H-1B workers are paid a market rate according to local standards; i.e., the same wage an equivalent U.S. worker (defined as a U.S. citizen or lawful permanent resident) would earn in a similar occupation and in the same local area—and that H-1B workers are paid no less than U.S. workers who are coworkers doing similar jobs for the same employer. This ensures that H-1B workers are paid a fair wage and are not being cheated, and that wages and conditions for U.S. workers are not undercut by firms underpaying their H-1B employees. In sum, the wage requirement is intended to remove the financial incentive employers might have to prefer an H-1B worker over a U.S. worker because the H-1B worker can be paid less.

The statute that establishes the H-1B program requires the hiring firm to file a labor condition application (LCA) to the secretary of labor, attesting it will adhere to the H-1B wage requirement.12 The text box includes the relevant language from 8 U.S.C. §1182(n):

Section of H-1B law that requires employers to pay the higher of the actual or prevailing wage

8 U.S.C. § 1182(n) Labor condition application

(1) No alien may be admitted or provided status as an H–1B nonimmigrant in an occupational classification unless the employer has filed with the Secretary of Labor an application stating the following:

(A) The employer-

(i) is offering and will offer during the period of authorized employment to aliens admitted or provided status as an H–1B nonimmigrant wages that are at least

(I) the actual wage level paid by the employer to all other individuals with similar experience and qualifications for the specific employment in question, or

(II) the prevailing wage level for the occupational classification in the area of employment,

whichever is greater, based on the best information available as of the time of filing the application, and

(ii) will provide working conditions for such a nonimmigrant that will not adversely affect the working conditions of workers similarly employed.

In short, the law requires that an H-1B worker must be paid the greater of the actual wage or the prevailing wage. The “actual” wage is determined by the wages paid to U.S. workers who are already employed by the firm and tasked with similar duties. The “prevailing” wage is, in layman’s terms, what most workers engaged in similar work in the same geographic area earn. It is typically set according to DOL survey data that corresponds to the local area and occupation, and is divided into four levels that purport to correspond to education and skill levels.13

Much policy discussion about the wage requirement has focused on raising the low prevailing wage levels set by DOL, something we have published on extensively—and which all major H-1B employers take advantage of to legally underpay H-1B workers, not just outsourcing firms.14 Numerous bills have been introduced in prior Congresses to substantially raise the prevailing wage level, most of them bipartisan.15 In addition to congressional efforts, there have been recent executive branch proposals to reform the calculations used to set the prevailing wage levels, in order to make them better reflect true market wages—a change DOL has clear authority to undertake.16 Nevertheless, DOL delayed, until November 2022, the effective date of a final rule it had issued previously that would have raised H-1B prevailing wages, and that was supported by worker advocates.17 By its own calculations, DOL’s decision to delay the effective date is costing H-1B workers tens of billions of dollars in wages.18 In its most recent regulatory agenda, DOL indicated that the rule would undergo another round of rulemaking in November 2021, likely meaning it would replace the final rule with an updated one.19

Precious little focus, however, has been placed on the other wage requirement stipulation, which requires H-1B employers to pay its H-1B workers at least the same “actual wage” that each employer pays to the U.S. workers it also employs in similar occupations. (U.S. workers in this case means U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents.) The rule states plainly and clearly that an H-1B employer must pay its H-1B employees “wages that are at least…the actual wage level paid by the employer to all other individuals with similar experience and qualifications for the specific employment in question.”20

The HCL presentation shines a spotlight on how government enforcement of the H-1B actual wage requirement has been negligent—and as far as we know, DOL has never investigated nor enforced this rule—and now we have new insight into how HCL appears to be flouting it with total impunity.

HCL presentation is evidence the company is likely violating the ‘actual wage’ requirement of the H-1B law by paying virtually all its H-1B employees far less than U.S. citizens in same roles

The HCL presentation details the company’s strategy for determining the number of H-1B applications (referred to as “nominations” in the document) to be filed, for which lines of business (LoBs), and for which job roles.

HCL segregates its workforce into four status categories to conduct its analysis for constructing its H-1B workforce:

- Citizen: U.S. citizens and permanent residents employed by HCL

- Landed–Visa Dependent: H-1B workers hired abroad, almost exclusively in India, by HCL and sponsored by HCL to come to the United States

- Local–Visa Dependent: H-1B workers who already were present in the United States working for other employers when they were hired by HCL and subsequently transferred their visas to HCL

- TP or Third Party: Workers hired through contractor firms

In the presentation, HCL lists each status in columns along with head counts, abbreviated as “HC,” as well as “ARC,” meaning additional resource cost, which represents wages for the citizen, landed, and local categories, but costs to the company for the third party category. (See the Appendix for more information on the document and the terms used in the document.) The presentation also, importantly, calculates the cost difference between each status. For example, Citizen vs. Landed ARC is the percentage premium HCL pays its workers who are U.S. citizens relative to the H-1B employees that it hired from India, for each job role. The formula is as follows:

Citizen vs. Landed ARC = (Citizen ARC−Landed ARC) ÷ Landed ARC

According to table after table in the document, H-1B workers both hired in India and in the U.S. are shown to be vastly underpaid compared with their U.S. citizen and permanent resident counterparts not hired with H-1B visas (referred to in this report as “U.S. workers”). According to HCL’s own calculations, the firm systematically pays H-1B workers much less than its U.S. workers—as much as 47%—contravening HCL’s attestations in its visa applications where it promises to pay the actual wage if it is higher than the prevailing wage.21

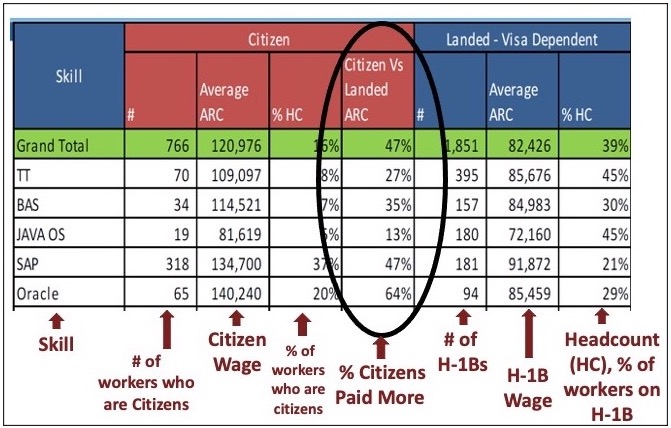

Paying H-1B workers less than U.S. workers is a competitive strategy HCL appears to have perfected. According to its own document, HCL underpays H-1B workers in virtually all jobs across all business lines, and it carefully manages and tracks wage differentials. For example, see Figure A, which is an image of one of HCL’s tables, along with our annotations. The column labeled “Citizen Vs Landed ARC,” which is circled, shows that citizens are paid more than landed H-1B workers for all jobs. In each case throughout HCL’s presentation, the percentage difference that U.S. citizens are paid more is very large, ranging from 13% to 87%.

In virtually every skill and job role, HCL systematically pays H-1B workers hired in India less than U.S. citizens and permanent residents: Image of table in internal HCL Technologies document comparing wages paid to U.S. citizens (and permanent residents) with wages paid to Landed (India-hired) H-1B visa holders, by primary skill used in job

Note: Annotations and arrows added by authors. List of abbreviations: “JAVA OS” is Java Operating System, “SAP” is the name of a common and widely used enterprise resource planning software, "ARC" is additional resource cost, and “HC” is head count. The authors cannot be certain of which skills or programs “TT” and “BAS” represent.

Source: Adapted from HCL, “Guidelines for H1 Nominations,” Exhibit 57. Case 3:19-cv-01185-MPS Document 48-57, filed September 7, 2021, at page 11. From United States of America, ex rel. Ralph Billington, Michael Aceves, and Sharon Dorman (Plaintiffs) v. HCL Technologies LTD. and HCL America, INC. (Defendants). Fourth Amended Complaint for Violations of the False Claims Act. United States District Court for the District of Connecticut. Civil Action No. 3:19-CV-1185 (MPS).

While violations for underpaying Local-Visa Dependent H-1B workers exist, our examples here focus on the pay differential between HCL’s U.S. and Landed-Visa Dependent workers because the presentation is the company’s strategy for hiring new H-1B workers from India;22 i.e., new Landed-Visa Dependent workers.

Table 1 highlights the final listed occupation in the image: HCL’s employees with expertise with Oracle databases. As the table shows, HCL pays its Oracle database experts who are U.S. citizens $140,240 per year, but the H-1B employees hired in India in the same job, in the same line of business, and with the same skills, just $85,459, a difference of nearly $55,000. Put another way, HCL pays its U.S. Citizen Oracle database experts 64% more than its Landed-Visa Dependent H-1B workers doing the exact same job (HCL calculates this in the Figure A column titled “Citizen Vs Landed ARC”). According to the plain language of the H-1B statute, HCL is required to pay its H-1B Oracle database experts with H-1B visas $140,240, because that is the “actual wage” it pays its U.S. citizen employees in the same job. Further, HCL’s notes in the document reveal that it applies for more H-1B workers for Oracle database job roles precisely because the cost differences between H-1B and U.S. workers are so great.

At HCL, Oracle experts with H-1B visas are paid $55,000 less than U.S. workers: Annual wages of HCL Oracle experts by immigration status of worker, 2015

| U.S. citizen or permanent resident | H-1B visa worker, hired in India | Wage premium for U.S. worker | % by which U.S. citizen wage exceeds H-1B wage |

|---|---|---|---|

| $140,240 | $85,459 | $54,781 | 64% |

Note: As these data show, HCL Technologies Inc. is in violation of the law requiring that H-1B employers pay H-1B visa holders at least as much as employees in the same jobs who are U.S. citizens or permanent residents. As evident in HCL’s internal guidelines for deciding which jobs to fill with new H-1B visa holders, the IT outsourcing company seeks H-1B workers for positions where there are large wage differences between visa holders and U.S. citizens: “[H-1B] Nominations proposed [are based on]…Skills where the cost differences between Landed [H-1B] and Local [U.S. Citizen] hires are over 40% - Example BI, SAP and Oracle skills.”

Source: Authors’ analysis of HCL, “Guidelines for H1 nominations,” Exhibit 57. Case 3:19-cv-01185-MPS Document 48-57, filed September 7, 2021, at page 11. From United States of America, ex rel. Ralph Billington, Michael Aceves, and Sharon Dorman (Plaintiffs) v. HCL Technologies LTD. and HCL America, INC. (Defendants). Fourth Amended Complaint for Violations of the False Claims Act. United States District Court for the District of Connecticut. Civil Action No. 3:19-CV-1185 (MPS).

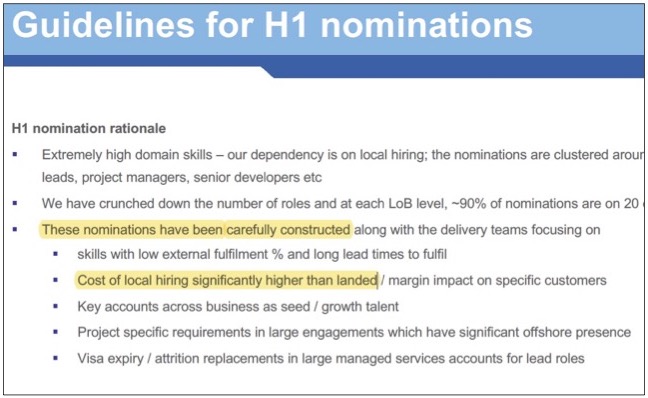

Another part of the document, shown in Figure B (see text we have highlighted in yellow), illustrates how HCL organizes its H-1B application pool around specific guidelines. HCL says its H-1B nominations (i.e., applications), have been “carefully constructed” to favor submitting applications for H-1B workers in job roles with the highest wage gap between U.S. and H-1B workers, demonstrating a clear intent to maximize profits by abusing the H-1B program to illegally underpay migrant workers. HCL’s H-1B criteria include: “Cost of local [U.S. citizen] hiring significantly higher than landed [H-1B visa worker hired in India].”

HCL ‘carefully constructs’ its H-1B pool to favor jobs with widest wage gap between H-1B workers and U.S. citizens and permanent residents: Image of part of slide in internal HCL Technologies document explaining its rationale for choosing which jobs it seeks to fill by applying for H-1B visas ("nominations")

Note: Yellow highlighting added by authors.

Source: Adapted from HCL, “Guidelines for H1 nominations,” Exhibit 57. Case 3:19-cv-01185-MPS Document 48-57, filed September 7, 2021, at page 2. From United States of America, ex rel. Ralph Billington, Michael Aceves, and Sharon Dorman (Plaintiffs) v. HCL Technologies LTD. and HCL America, INC. (Defendants). Fourth Amended Complaint for Violations of the False Claims Act. United States District Court for the District of Connecticut. Civil Action No. 3:19-CV-1185 (MPS).

Throughout the presentation, HCL targets H-1B applications for job roles where hiring local (i.e., U.S. citizens or permanent residents; Local-Visa Dependent; and, Third Party) is more expensive than “landed” H-1B visa holders who were recruited in India. In its analysis of every line of business throughout the presentation, HCL states explicitly that the large wage differential between hiring local and these H-1B workers from India is the critical factor in determining which jobs HCL wishes to fill with these H-1B workers. For example, it notes on page 7 that “Local hiring is ~30% more expensive than landed,” on page 8 that “local hiring is 36% more expensive than landed,” and on page 9, that “local hiring ARC is 58% more expensive compared to landed ARC.” On page 11, HCL notes that “70% of nominations [for H-1B] are across 6 skill groups, which have an average of 62% fulfillment and where local hiring is 70% more expensive than landed [H-1B].”23 All of these excerpts illustrate how the significant cost savings HCL gains from hiring much-lower-paid H-1B workers is central to the firm’s H-1B hiring strategy through all of its lines of business.

HCL is also affirming here that its H-1B and U.S. worker employees are “similarly employed” by directly comparing wages of H-1B workers with U.S. workers within job roles. “Citizen Vs Landed [H-1B] ARC” wage savings, as shown in Figure A, is the key variable in the firm’s analysis. Further, HCL repeatedly states that “Local Hiring is [X]% more expensive than Landed [H-1B],” with the goal of targeting new H-1B applications in those job roles where the wage differential is greatest. This demonstrates that HCL has determined that H-1B workers can take on the same positions—in other words are substitutes for—currently employed U.S. workers in those job roles, i.e., they are similarly employed, as envisioned in the statute cited in the text box “Section of H-1B law that requires employers to pay the higher of the actual or prevailing wage,” 8 U.S.C. § 1182(n).

HCL appears to be stealing at least $95 million per year in wages from its H-1B employees

So, what do all of HCL’s strategies and policies on H-1B hiring amount to in terms of wage savings on labor costs for HCL? By taking the number of all H-1B workers, landed and local, who appear to be illegally underpaid from the HCL document, and the amounts that each appear to be underpaid by, compared with their U.S. citizen and permanent resident co-workers who are doing the same jobs—we estimate that HCL is saving at least $95 million per year by illegally underpaying its H-1B employees. That’s $95 million in stolen wages from H-1B workers every year—white-collar wage theft on a grand scale—which has been facilitated by negligent labor standards enforcement in the H-1B program. (See Appendix for a detailed explanation of our methodology.)

HCL is a top H-1B recipient and large player in the tech industry—and has been involved in recent H-1B abuse scandals

HCL is not a small outsourcing firm. It is India’s third-largest IT outsourcing firm, generating 63% of its $11 billion in revenue in the United States.24 HCL is a staffing firm that outplaces nearly all its H-1B workers at hundreds of customer sites for well-known corporations, including USAA, Merck, Google, T-Mobile, Boeing, Keurig Dr Pepper, FedEx, Intel, Deutsche Bank, Pentagon Federal Credit Union, Cisco, Disney, University of California, and Microsoft.25

Despite being a major player in the industry and working closely with most of the household names headquartered in Silicon Valley, HCL has been at the center of multiple H-1B program-related scandals that have made headlines and the front pages in recent years. The most notable were at Disney and the University of California, where U.S. workers were laid off, but first forced to train their H-1B replacements supplied by HCL, who were paid tens of thousands of dollars less per year.26

Nevertheless, the scale and magnitude of HCL’s apparent abuse and legal violations of the H-1B program suggested by their internal document is stunning, especially considering the number of H-1B workers HCL has employed over the years. Last year, HCL ranked eighth in total H-1B approvals with more than 4,000: 1,405 new visas and 2,801 visa renewals. Over the past dozen years, HCL consistently has been one of the largest H-1B employers, receiving a total of 31,000 H-1B visa approvals from USCIS since 2009.27

Lack of enforcement invites outsourcing employers like HCL to underpay migrant workers

The Department of Labor’s flawed legal reasoning, lax application requirements, and negligent enforcement have opened the door for outsourcing firms like HCL to underpay migrant workers with impunity and to create an entire business model around it. For many years, outsourcing firms have exploited a loophole created by DOL’s flawed interpretation of the H-1B statute. The statute requires U.S. employers to attest that their use of the H-1B program “will not adversely affect the wages and working conditions of workers in the United States similarly employed.”28 Customers like Disney, seeking to save money by replacing their U.S. workers with H-1B employees who are paid substantially less, dodge the wage and working condition requirements by simply outsourcing the H-1B hiring to a contractor like HCL. By doing so, HCL, not Disney, is directly hiring the lower-paid H-1B worker, and the U.S. worker being replaced is employed by Disney, not HCL. DOL has wrongly interpreted the H-1B statute to mean it is only violated in cases where an employer adversely affects the conditions of the employer’s own, direct employees (HCL in the Disney example). By doing so, DOL is incentivizing and subsidizing the outsourcing of jobs to lower-paid contract workers in the technology labor market—a fissuring that degrades the wages and working conditions of H-1B workers and U.S. workers alike.

In sum, DOL has determined it is acceptable for an employer to underpay an H-1B worker, even if U.S. workers are obviously being harmed (they are being laid off and replaced, after all), as long as the H-1B worker is hired through a contractor like HCL. This DOL interpretation appears to be irrational and unjustified, and is the main reason why the dozens of news reports chronicling thousands of U.S. workers training their H-1B replacements—at Disney, the University of California, New York Life, Mass Mutual, Southern California Edison, etc.—have never resulted in a single penalty or any change in business behavior.29 In every reported case, the lower-paid H-1B worker was hired and employed by an outsourcing firm. DOL can easily close the outsourcing loophole it created (more on that later), but the HCL presentation reveals a type of abuse that even the DOL cannot ignore.

The presentation shows HCL pays its own H-1B employees less than its own directly employed U.S. workers, which appears to be a clear violation of the H-1B “actual wage” requirement, even under DOL’s current interpretation. The DOL, the Department of Homeland Security, and Department of Justice should investigate this large-scale malfeasance.30 If violations are found, the government should levy a punishment sufficient to change behavior and deter future violations by HCL and other employers, as well as order HCL to pay back wages to affected H-1B workers. Further, government agencies should restructure their oversight of the H-1B program to ensure compliance, protecting H-1B workers from wage theft and U.S. workers from being undercut now and in the future.

Violating the actual wage requirement is likely an industrywide practice

More than 14 years ago, Sens. Richard Durbin (D-Ill.) and Charles Grassley (R-Iowa) uncovered that outsourcing firms rather than traditional technology ones were the largest H-1B employers.31 Outsourcing firms like HCL have continued to dominate the H-1B program ever since. The outsourcing business model relies on supplying labor services to clients, and the ability to secure lower-cost workers is a significant comparative advantage. Exploiting the vulnerabilities in the H-1B program—vulnerabilities created both by statute and governance—is fundamental to the viability of these companies. As a result, the revelations uncovered in the HCL document, combined with available data on the H-1B program, suggest that violating the actual wage requirement is likely an industrywide practice among outsourcing firms.

In order to still reap a profit for themselves as middlemen, the outsourcing firms have to offer clients a way to cut costs. Since IT services is a labor-intensive business—more than 75% of overall costs are for labor—the only way to cut costs for the client and at the same time earn a profit is by finding workers who are significantly less expensive to employ than the U.S. workers already employed by the client.32 The outsourcing firms derive these savings by offshoring as much work as possible to low-cost countries like India, where salaries are often 90% lower than U.S. salaries, coupled with recruiting and hiring H-1B workers at salaries much lower than the salaries paid to U.S. workers.33

To illustrate, Table 2 below shows the top 10 H-1B employers in fiscal year (FY) 2015, according to government data available from USCIS. (FY15 was selected because it corresponds with the timeframe of HCL’s planning document.) It shows the top eight H-1B employers in that period were firms with the same outsourcing business model as HCL. They all pay similarly low average salaries for IT jobs, ranging from $69,000 to $82,000 (HCL is at $81,000, a salary consistent with the salaries listed in the slides of their presentation). This is not surprising, since HCL competes head to head with these same firms, and it is common knowledge that firms within an industry mimic the most profitable practices within a sector. In the IT outsourcing sector, the most profitable practice is exploiting the H-1B program. In contrast, Microsoft and Google—which are not outsourcing firms—ranked 9th and 10th in terms of the most H-1B approvals, respectively, and pay substantially more in salary to their H-1B workers: $121,000 and $131,000. In Google’s case, it paid 89% more to its H-1B employees in 2015 than Tata Consultancy Services(TCS)—a major outsourcing firm like HCL—paid its H-1B workers.

Eight of top 10 H-1B employers in fiscal year 2015 used HCL’s outsourcing business model: All eight outsourcers compete with one another and pay H-1B workers relatively low salaries

| Rank | Employer name | H-1B petition approvals for initial and continuing employment, FY 2015 | Average salary for H-1B employees | Outsourcing business model similar to HCL? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cognizant Technology | 15,547 | $82,351 | Yes |

| 2 | Infosys | 7,989 | $82,156 | Yes |

| 3 | Tata Consultancy Services | 7,936 | $69,252 | Yes |

| 4 | Wipro | 5,968 | $72,711 | Yes |

| 5 | Accenture | 5,445 | $76,233 | Yes |

| 6 | IBM Corp. | 2,815 | $75,516 | Yes |

| 7 | Tech Mahindra Americas | 2,553 | $73,456 | Yes |

| 8 | HCL America | 2,548 | $81,317 | Yes |

| 9 | Microsoft | 2,523 | $120,944 | No |

| 10 | 2,023 | $130,872 | No |

Note: H-1B petition approvals include approved petitions for both initial employment (i.e., for new employment, not visa extensions) as well as continuing employment (i.e., visa extensions). Petitions are approved by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), a subagency of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Average wage data come from USCIS and include all of the H-1B visa holders employed by HCL, whether hired in India or the United States.

Source: USCIS, "Approved H-1B Petitions (Number, Salary, and Degree/Diploma) by Employer, Fiscal Year 2015," Buy American and Hire American [data page] (archived content from June 30, 2017), accessed October 22, 2021.

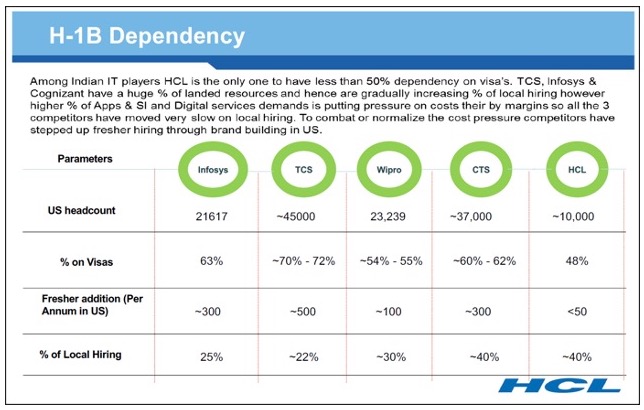

In Figure C, which comes from HCL’s presentation, HCL underscores its competitors’ dependence on H-1B visas. Those competitors—Infosys, TCS, Wipro, and CTS (Cognizant Technology Solutions)—were the top four recipients of H-1B approvals in FY15 (as shown in Table 2).

HCL’s top four competitors also depend heavily on H-1B visas: Image of table in internal HCL Technologies document showing HCL’s direct competitors were the top four overall recipients of H-1B visas in fiscal year 2015

Note: List of abbreviations: "TCS" is Tata Consultancy Services and "CTS" is Cognizant Technology Solutions.

Source: Adapted from HCL, “Guidelines for H1 nominations,” Exhibit 57. Case 3:19-cv-01185-MPS Document 48-57, filed September 7, 2021, at page 16. From United States of America, ex rel. Ralph Billington, Michael Aceves, and Sharon Dorman (Plaintiffs) v. HCL Technologies LTD. and HCL America, INC. (Defendants). Fourth Amended Complaint for Violations of the False Claims Act. United States District Court for the District of Connecticut. Civil Action No. 3:19-CV-1185 (MPS).

All of this suggests that HCL’s approach to exploiting the H-1B program is the norm, and not an exception or an outlier. The data show that all firms with an outsourcing business model pay similarly low wages to their H-1B workers, which suggests these firms within the IT industry are mimicking one another’s competitive advantage of exploiting the H-1B program. The new information we have about HCL, in tandem with existing information about other outsourcing firms, strongly suggests that all of the biggest H-1B outsourcing firms likely are violating the H-1B program’s actual wage requirement, especially considering that we know now that they all employ significant numbers of U.S. workers (as shown in Figure C, under “US headcount” and “% on Visas”).34

DOL should close the H-1B outsourcing loophole created by its flawed statutory interpretation

Some additional discussion about how the H-1B outsourcing loophole operates is warranted. In previous cases that DOL has investigated, including at Disney, DOL asserted that HCL’s practice of paying H-1B workers tens of thousands of dollars less in wages than what the client company—Disney—was paying its own workers was perfectly legal because the H-1B actual wage requirement does not apply when compared with U.S. workers employed by a customer’s company. Of course, such an interpretation is wrong and flies in the face of the intent of Congress to protect both H-1B and U.S. workers. Through this flawed interpretation, DOL invites firms to abuse the H-1B visa, and the subsequent abuse has turned the H-1B into what some have dubbed the “outsourcing visa.”35

DOL’s flawed interpretation also has incentivized the widespread fissuring of the IT services industry. As documented by scholars such as David Weil, replacing employees with contract workers leads to lower-quality jobs, lower wages and benefits, greater job insecurity, and a shift of risk from employer to worker without concomitant reward.36 Disney and every other major employer has enormous financial incentive to outsource jobs to firms like HCL, and these firms in turn exploit the H-1B program because it allows them to pay lower wages and offer fewer benefits and poorer working conditions to migrant workers who are tied to temporary visas and have very little bargaining power. DOL should be working to limit unwarranted fissuring, but instead the agency is incentivizing and accelerating widespread fissuring in the IT services labor market, thereby degrading wages and working conditions for U.S. and migrant workers alike.37

How companies contract with H-1B outsourcing firms to evade H-1B visa rules that protect wages and working conditions

When filing an H-1B application, employers must attest to meeting two requirements that are intended to protect labor standards. These two protections work in tandem to ensure that U.S. workers are not undercut or adversely impacted by the employment of H-1B workers, and to ensure that H-1B workers are paid fairly.

- Wage Rule: Employers must attest that they will pay the higher of the prevailing wage (the wage that workers engaged in similar work earn in the local labor market, as set by the U.S. Department of Labor in four tiers based on experience) OR the actual wage (the wage the company pays citizens or lawful permanent residents doing the same work at the company).

- Adverse Effect Rule: Employers must attest that employing H-1B workers will not adversely affect the wages and working conditions of workers in the U.S. who are similarly employed.

We illustrate how companies routinely evade these rules with a real example: If Disney sought to replace its incumbent U.S. employees in its IT department with H-1B employees, it would violate the Adverse Effect Rule above. Clearly, replacing U.S. employees with H-1B employees would adversely affect those U.S. employees. If Disney paid its H-1B employees less than what it pays its U.S. employees it would violate the Wage Rule. The Wage Rule ensures that H-1B workers are not being hired instead of U.S. workers because they are less expensive to employ, that H-1B workers are paid fairly, and that U.S. workers’ wages are not undercut.

Disney evades these protections by outsourcing the employment of the H-1B workers to HCL. HCL employs the H-1B workers, with Disney laying off its U.S. workers and replacing them with HCL’s H-1B workers. While this is contrary to the intent of the program and an obvious violation of the Adverse Effect Rule, DOL has deemed it legal.

When HCL files its H-1B applications it must attest it is meeting both the Wage and Adverse Effect Rules. However HCL is paying its H-1B workers less than Disney’s U.S. workers, violating the Wage Rule, and it is replacing Disney’s U.S. workers, thus violating the Adverse Effect Rule. Nevertheless, DOL maintains that HCL is violating neither rule. How is this possible? Because the agency considers only workers directly employed by HCL when assessing adverse impacts on similarly employed U.S. workers, thus excluding Disney’s workers from HCL’s obligations.

DOL has (wrongly) interpreted the law so that Disney is not considered an employer of the H-1B workers hired by HCL, even though all their work product benefits Disney. So, HCL needs to only the meet Wage and Adverse Effect Rules for directly employed HCL workers.

To meet the intent of the worker protections in the H-1B law, DOL should require that Disney also attest to the Wage and Adverse Effect Rules for HCL’s H-1B employees staffing Disney. That way HCL’s H-1B employees are clearly included in both firms’ filings. That would be the rational way to interpret the law so it protects both sets of workers.

The upshot is that under DOL’s current flawed interpretation of the law, Disney absolves itself of having to comply with the Wage and Adverse Effect Rules simply by contracting out the employment of H-1B workers to HCL.

Through this loophole, DOL is also incentivizing and accelerating offshoring, the movement of high-wage jobs from the United States to lower-cost countries. Outsourcing and offshoring are only viable as a business model when they are done in conjunction. HCL’s business model is to replace the customer’s U.S. workers with a blend of workers who are located offshore (India in HCL’s case), and onsite in the United States. Not all jobs and tasks can be sent offshore, however. Some significant share of jobs, due to the nature of their tasks, are geographically sticky and require physical presence in the United States. The typical offshore to onsite labor ratio in the industry is 70:30; i.e., 70% of the workers are located offshore and 30% of the workers are onsite in the United States.38 Firms like HCL reap substantial cost savings by moving work and tasks to its employees in low-cost countries like India, where wages are 90% less than U.S. wages. But those cost savings alone are not sufficient to make it worthwhile for the customer to outsource to HCL. Outsourcers must find additional cost savings from its workers onsite in the United States. The ability to hire H-1B workers at lower costs than similarly skilled U.S. workers is the linchpin for making the outsourcing-offshoring business proposition attractive to customers. Customers expect to cut labor costs sufficiently to counterbalance the additional risk they take on by outsourcing, loss of managerial control, and negative publicity from outsourcing and offshoring. If underpaying H-1B workers was off the table, as it should be, HCL could not offer sufficient overall savings to customers like Disney, who in turn would be much less likely to outsource and offshore their in-house workforce.

DOL issued policy guidance this year to fix the outsourcing loophole it has de facto created. Under the proposed guidance,

…when a primary employer places an H-1B worker with a secondary employer that is a common law employer of the H-1B worker, such as when a staffing agency places a software engineer with certain technology firms, the secondary employer, in addition to the primary employer, must file a petition and an LCA.39

In the HCL example, this proposed change would have required secondary employers like Disney to file LCAs for H-1B workers placed at its worksites, attesting that it will not adversely affect the wages and working conditions of workers at either company. This would be a major leap forward in stamping out abuse, because the ability of outsourcing firms to place lower-paid H-1B workers at client sites—in these secondary employer arrangements—has been the most common way the H-1B program has been used for at least the past 15 years. Yet, DOL subsequently abandoned the policy guidance, providing no explanation and offering no indication of the future of the policy.40

The Labor Department has the legal authority to investigate H-1B wage theft

In recent cases of H-1B abuses, including those cited here, DOL’s Wage and Hour Division (WHD)—which is “responsible for ensuring that workers are receiving the wages promised on the LCA and are working in the occupation and at the location specified”41—has appeared reluctant to use its authority to investigate what have appeared to be blatant violations of the H-1B wage requirements. And even when the department has investigated, as noted earlier, its flawed interpretation of the law has resulted in no penalties against employers nor any change in behavior among outsourcing firms and the client firms that contract with them. Nevertheless, even with the current flawed legal interpretation with respect to the outsourcing loophole, WHD has significant authority to investigate the types of abuses we have described in this report, in terms of the H-1B actual wage requirement.

WHD’s own fact sheet lists four circumstances under which it is authorized to initiate an investigation related to the H-1B program:

-

- WH [Wage and Hour Division] receives a complaint from an aggrieved person or organization;

- WH receives specific credible information from a reliable source (other than a complainant) that the employer has failed to meet certain LCA conditions, has engaged in a pattern or practice of failures to meet such conditions, or has committed a substantial failure to meet such conditions that affects multiple employees;

- The Secretary of Labor has found, on a case-by-case basis, that an employer (within the last five years) has committed a willful failure to meet a condition specified in the LCA or willfully misrepresented a material fact in the LCA. In such cases, a random investigation may be conducted; or

- The Secretary of Labor has reasonable cause to believe that the employer is not in compliance. In such cases, the Secretary may certify that an investigation be conducted.42

With respect to the bullet points above, the relevant details are provided in the H-1B statute at 8 U.S.C. 1182(n)(2)(G).43 Subsection (i) clearly states that the secretary of labor may investigate an H-1B employer if the secretary “has reasonable cause to believe that the employer is not in compliance.” Subsection (ii) is also straightforward, giving the secretary authority to investigate when he or she has received credible information from a source:

If the Secretary of Labor receives specific credible information from a source, who is likely to have knowledge of an employer’s practices or employment conditions, or an employer’s compliance with the employer’s labor condition application under paragraph (1), and whose identity is known to the Secretary of Labor, and such information provides reasonable cause to believe that the employer has committed a willful failure to meet a condition of paragraph (1)(A), (1)(B), (1)(C), (1)(E), (1)(F), or (1)(G)(i)(I), has engaged in a pattern or practice of failures to meet such a condition, or has committed a substantial failure to meet such a condition that affects multiple employees, the Secretary of Labor may conduct an investigation into the alleged failure or failures. The Secretary of Labor may withhold the identity of the source from the employer, and the source’s identity shall not be subject to disclosure under section 552 of title 5, United States Code.

HCL’s own internal document that has been made public through litigation, as well as the claims made by the whistleblowers involved in the False Claims Act lawsuit against HCL, are credible sources of specific information that, under current law, should trigger a DOL investigation of HCL’s H-1B program practices. There is perhaps no more credible source than the employer itself, HCL, and in addition, the federal district court that has admitted HCL’s presentation into the official record is another obviously credible source.

The labor secretary’s authority to investigate HCL’s failures to pay the correct wage rates to their H-1B employees in past years (HCL’s internal document lists salaries from 2015) may be temporally limited, however, by 8 U.S.C. 1182(n)(2)(G)(vi). That section of the statute provides that the secretary must receive the information that could be the basis for an investigation related to an H-1B labor condition application (LCA) “not later than 12 months after the date of the alleged failure” of an employer to comply with the attestations in the LCA. However, the corresponding regulation at Section 5 of 20 C.F.R. §655.806(a)44 further defines how the 12-month statute of limitations operates:

(5) A complaint must be filed not later than 12 months after the latest date on which the alleged violation(s) were committed, which would be the date on which the employer allegedly failed to perform an action or fulfill a condition specified in the LCA.

In practical terms, this means that if an employer did not pay the correct wage six months ago—even if the corresponding LCA was filed six years ago—then a complaint could still be filed validly according to the 12-month rule.45

In addition, according to case law from DOL’s Administrative Review Board, complaints about H-1B violations can be equitably tolled, meaning that an exemption from the 12-month limitation could apply if the plaintiff (for example, an aggrieved H-1B worker) could not have reasonably discovered the legal violation until after the 12-month period had expired.46 Equitable tolling would be warranted if a complainant was misled by their employer, prevented from asserting rights due to extraordinary circumstances, or the complainant raised the correct claim but mistakenly filed it in the wrong forum.47

Furthermore, Section 5 of 20 C.F.R. §655.806(a) also clearly states that WHD may assess remedies and back wages that are owed from more than 12 months prior, as long as they are related to a complaint that was validly filed within the 12-month jurisdictional limit in the statute:

This jurisdictional bar does not affect the scope of the remedies which may be assessed by the Administrator. Where, for example, a complaint is timely filed, back wages may be assessed for a period prior to one year before the filing of a complaint.

In addition, because H-1B visas are valid for up to six years, and often for longer when applications for permanent residence are filed for an H-1B worker, many of HCL’s current H-1B employees may have been hired in the years prior to or during fiscal year 2015. As a result, the secretary of labor, through WHD, would be justified in initiating an investigation, because the apparent wage theft and LCA violations uncovered in the HCL document likely are still ongoing (meaning they would fall within the 12-month limitation).

In any case, even if HCL cannot be penalized for providing false information on LCAs in previous years, due to the 12-month limit, the information presented here and in the whistleblower lawsuit is evidence of an ongoing pattern and practice by HCL—which justifies the initiation of an investigation into HCL’s current practices. HCL’s internal document suggests that the firm is likely to still be carrying out its strategy and explicit policy to systematically and unlawfully underpay its H-1B employees compared with similarly employed U.S. workers, in violation of the H-1B actual wage requirement. WHD therefore should investigate HCL and other outsourcing firms with the aim of making as many H-1B workers whole as it possibly can—through repayment of back wages that are owed, under its existing authority—and levy any other fines and penalties that can serve as a deterrent against future violations, including debarring HCL or other outsourcing firms from hiring through the H-1B program.

Finally, it should be noted that, as WHD’s fact sheet shows, H-1B enforcement is largely based on the receipt of complaints about an employer’s specific wrongdoing. However, complaints from H-1B workers themselves to DOL are unlikely since it would require an H-1B worker to blow the whistle on their own employer, the same employer that controls the H-1B worker’s immigration status and ability to remain in the United States. That’s another compelling reason why WHD should be more proactive and take action to enforce the law and protect H-1B workers from wage theft based on the existing evidence that has been made public through revelations in the HCL litigation.

Conclusion and recommendations

HCL Technologies, India’s third-largest IT outsourcing firm and the eighth-largest employer of college-educated migrant workers with H-1B visas in the United States, appears to be violating U.S. law by vastly underpaying migrant workers and lying on forms it submits to the U.S. Department of Labor to obtain visas for its workers. Specifically, corporate documents suggest that the firm is not—as it attests on those forms—paying H-1B migrant workers the greater of the prevailing wage or the actual wage paid to U.S. workers it employs in the same job roles. Rather, the documents show HCL is paying its H-1B workers tens of thousands of dollars less than it is paying U.S. citizens in those same jobs, in violation of the actual wage requirement. If true, the magnitude of the lawbreaking is stunning, with violations numbering in the tens of thousands. As noted above, based on the number of workers and average levels of underpayment at HCL, we estimate that the company is stealing roughly $95 million from H-1B workers every year. This wage theft is also degrading wages and labor standards for all workers in similar occupations, and the IT industry at large. Further, it allows HCL to offer its contract workers to such U.S. employers as Cisco, Disney, Google, and other firms at a much lower cost than the workers that competitor outsourcing firms can reasonably offer. In effect, U.S. immigration policy is being used to subsidize the outsourcing and offshoring of decent and high-paying U.S. jobs.

The cumulative loss of wages to workers in the United States—including both migrant workers and workers who are U.S. citizens—likely totals in the billions of dollars, just from the abuses of the H-1B program by one company. In 2020, 17 of the top 30 H-1B employers were outsourcing firms with business models similar to HCL’s, which means that the potential wage theft being facilitated similarly by other outsourcing firms through the H-1B program is at least an order of magnitude larger.

Immediate action should be taken to stop the apparent wage theft and abuse of the H-1B program by HCL that undercuts labor standards—as well as to stop abuses by other companies that might be violating the actual wage requirement—and to make H-1B workers whole. To help remedy this situation, we recommend that:

- Congress hold hearings to investigate visa program vulnerabilities uncovered by the HCL document.

- The Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division recover the full amount of back wages for all H-1B workers who have been the victims of HCL’s apparent violation of the H-1B actual wage requirement.

- The Department of Justice’s (DOJ) Civil Division, in conjunction with United States Citizenship and Immigration Services and DOL, vigorously prosecute visa fraud under the False Claims Act, consistent with a recent federal court decision applying the False Claims Act to H-1B visa fraud, as well as other visas used for skilled occupations, like the L-1 and B-1.48

- Congress request the Government Accountability Office and the Office of Inspector General at both the Department of Homeland Security and DOL, investigate the types of H-1B visa abuse that have been uncovered, along with other forms of abuse.

- The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and DOJ Office of Special Counsel investigate HCL’s compliance with anti-discrimination laws given its overt preference for H-1B workers over workers who are U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents.

- The Department of Labor’s Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs audit HCL and its clients (because many are federal contractors).

The Departments of Labor and Homeland Security should also take immediate action—using existing legal authority—to improve other aspects of the H-1B program and thereby protect labor standards. We urge that:

- DOL vigorously enforce the attestations made by H-1B employers on their applications, including the wage and working conditions requirements.

- The secretary of labor has the statutory authority to initiate an investigation and should use it. HCL’s own document, the whistleblowers in the False Claims Act lawsuits, and the federal district court that is acting as the forum for the litigation are all credible sources that justify the initiation of an investigation.

- DOL fix the outsourcing loophole by issuing policy guidance requiring secondary employers of H-1B workers (the companies that hire firms like HCL to provide contract workers) to file labor condition applications. This would help stop DOL from artificially creating huge financial incentives leading to the fissuring of the IT labor market (the replacement of employees with contract workers with lower wages and fewer protections).

- DOL promulgate a regulation to increase the required minimum prevailing wage levels for H-1B jobs to reflect true market wages.

- DHS promulgate a regulation to allocate H-1Bs based on applications offering to pay the highest wages.

- DHS provide deferred action and employment authorization to any H-1B workers who are victims of employers found to have violated labor, employment, or immigration laws—including visa fraud.

- DHS and DOL permit and facilitate H-1B workers to become eligible to receive U visas (for victims of crime who assist law enforcement) if they come forward as whistleblowers and/or assist authorities in prosecuting lawbreaking employers.

Finally, Congress should pass legislation that implements lasting and much-needed reforms in the H-1B visa program and to stem abuses. We recommend that such legislation:

- Increase the H-1B wage requirements to reflect true market wages and allocate H-1Bs based on applications offering to pay the highest wages.

- Establish a labor market test that requires employers to prove a labor shortage exists before they can hire through the H-1B program.

- Allow H-1B workers to self-petition for permanent residence (i.e., ending employer sponsorship for green cards).

- Improve and enhance portability between employers for H-1B workers.

- Establish a robust post-entry auditing system to ensure employers are held accountable when they underpay H-1B workers and violate other labor and employment protections.

Appendix: Methodology for estimating annual underpayment and wage theft of H-1B workers

To estimate annual underpayment of HCL’s H-1B visa workers, we use data provided in the HCL document, “Guidelines for H1 nominations,” which is an exhibit in the recent False Claims Act whistleblower case filed against the company by former HCL employees in September 2021 (United States of America, ex rel. Ralph Billington, Michael Aceves, and Sharon Dorman (Plaintiffs) v. HCL Technologies LTD. and HCL America, INC.). The HCL presentation is a planning document for its fiscal year 2016 H-1B visa allotment, which the U.S. government opened April 1, 2015. Thus the document was likely created in late 2014 or early 2015. It used data on the company’s existing workforce to outline how the company would determine which positions it would seek to fill by applying for an H-1B visa for that position. The presentation includes detailed tables analyzing the additional resource costs (ARC) for each type of worker by worker-status for the three lines of business (LoB) in which most of HCL’s H-1B workforce is employed. The three LoBs are:

- Engineering and R&D services (ERS)

- Application development and systems integration (APPS & SI)

- IT Infrastructure management services and solutions (INFRA)

HCL segregates its workers into four status categories to perform its H-1B application analysis:

- Citizen: U.S. citizens and permanent residents employed by HCL

- Landed–Visa Dependent: H-1B workers hired in India and sponsored by HCL to come to the U.S.

- Local–Visa Dependent: H-1B workers who were already present in the United States working for other employers but who were hired by/transferred their visas to HCL

- TP or Third Party: workers hired through contractor firms

For each of the three LoBs, HCL tables show headcounts (#) and compare the ARC for workers in the four status categories.

While the presentation does not define ARC, we infer from other evidence that ARC represents the average wage paid to the workers, not the average total cost of compensation, benefits, and taxes HCL incurs for its workers.

First, according to USCIS data, in fiscal year 2015 HCL paid its H-1B workers $81,317 (See Table 2 earlier in our report). This is wage-only data and is consistent with data in the HCL presentation.

Were the ARC to reflect all costs of compensation, the wages reflected would be implausibly low. The rule of thumb for employers is to add 27% to the direct cost of an employee to account for benefits (health care, leave, etc.). This is called the worker’s loaded cost.

So, the straight wage of someone with a loaded cost of $76,200 would be $60,000 ($76,200= 1.27 X $60,000). There are statutory policy constraints that create a de facto absolute wage floor of $60,000 for certain H-1B employers like HCL. The presentation says that the average wage for the Landed–Visa Dependent workers such as Sr. Mechanical Designer was $68,328. If that were the loaded rate then the wages for that position would be $53,802 (=$68,328/1.27), which would place HCL at significant legal risk.

Note that from a policy standpoint, whether the ARC is wages-only or loaded cost is immaterial since the H-1B workers must be paid wages and benefits at least as much as the firm’s similarly employed U.S. workers. Landed H-1B workers are receiving a substantially lower ARC than similarly employed U.S. citizens whether ARC is measuring wages-only or some combination of wages and benefits.

Within a specific LoB, multiple views of ARC differentials are presented by: project category, skill, or job role.

HCL tables for job role were used to estimate the wages because they provide the most disaggregated view and play a critical role in HCL’s H-1B application strategy to exploit H-1B-to-citizen wage gaps.

HCL’s underpayment is calculated for both its Landed–Visa Dependent and Local–Visa Dependent workers and then summed.

Appendix Table 1 shows how H-1B wage savings are estimated. The columns labeled “Savings from Landed H-1B” and “Savings from Local H-1B” show the calculations):

For each Job Role (Skill):

Landed H1B Savings=(Citizen ARC−Landed ARC) × Number of Landed

Local H1B Savings=(Citizen ARC−Local ARC) × Number of Local

Total Wage Savings is the sum of Landed + Local Savings for all job roles.

HCL’s overall wage savings is estimated by summing the underpayment for each position: Calculation is illustrated for two positions

| Skill | Citizen | Landed–visa dependent | Savings from landed H-1B | Local–visa dependent | Savings from local H-1B | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Average ARC | # | Average ARC | Underpayment for each landed H-1B = B − D | Savings is # of landed X amount of underpayment = C X D | # | Average ARC | Underpayment for each local H-1B = B − H | Savings is # of local X amount of underpayment = G X I | |

| Columns: | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J |

| Developer – senior | 92 | 115,713 | 169 | 81,070 | $ 34,643 | $ 5,854,667 | 61 | 97,614 | $ 18,099 | $ 1,104,039 |

| Technical lead | 132 | 122,661 | 343 | 81,023 | $ 41,638 | $ 14,281,834 | 100 | 98,944 | $ 23,717 | $ 2,371,700 |

| Total wage savings | SUM (Col F) | SUM (Col J) | ||||||||

Note: See text in Appendix for explanation of estimation methodology.

Source: Authors’ analysis of tables in HCL, “Guidelines for H1 nominations,” Exhibit 57. Case 3:19-cv-01185-MPS Document 48-57, filed September 7, 2021. From United States of America, ex rel. Ralph Billington, Michael Aceves, and Sharon Dorman (Plaintiffs) v. HCL Technologies LTD. and HCL America, INC. (Defendants). Fourth Amended Complaint for Violations of the False Claims Act. United States District Court for the District of Connecticut. Civil Action No. 3:19-CV-1185 (MPS).

Additional notes regarding our calculations:

- Job roles where the H-1B ARC is greater than the Citizen ARC are left out of the calculation because those workers cannot be identified as being underpaid the actual wage requirement.

- Workers listed as “Third Party” are not relevant for these calculations and were therefore not included because those workers are employed by another firm, not HCL.

- The detailed tables in HCL’s presentation include the vast majority, though not all, of HCL’s H-1B workers in those business lines. HCL presents the job roles with the most H-1B applications for each business line. For example, the ERS table shows only the subset of job roles that account for the most H-1B workers and applications. Further, some business lines that have H-1B workers are not included in HCL’s analysis. As a result, our estimates likely understate the cumulative underpayment to H-1B workers.

The cumulative wage savings for each of HCL’s major lines of business are:

- ERS = $18,380,591

- APPS & SI = $68,220,782

- INFRA = $8,053,730

The resulting total amount by which H-1B workers appear to be illegally underpaid by is:

$94,655,103

Endnotes

1. EPI has published reports detailing H-1B abuses dating back to 2007. See, for example, Ron Hira, Outsourcing America’s Technology and Knowledge Jobs: High-Skill Guest Worker Visas Are Currently Hurting Rather Than Helping Keep Jobs at Home, Economic Policy Institute, May 16, 2007; Ron Hira, Bridge to Immigration or Cheap Temporary Labor? The H-1B & L-1 Visa Programs Are a Source of Both, Economic Policy Institute, February 17, 2010. The New York Times published an investigative series in 2015, which included the following article: Julia Preston, “Large Companies Game H-1B Visa Program, Costing the U.S. Jobs,” New York Times, November 10, 2015. The CBS News show “60 Minutes” profiled H-1B abuses in 1993 (“North of the Border; American Businesses Are Importing Foreign Computer Programmers While American Programmers Are Unemployed,” March 19, 1993) and again in 2017 (“You’re Fired,” March 19, 2017.)

2. The H-1B visa program was created to fill labor shortages in high-skilled fields that require at least a college degree. While it has increasingly been dominated by employers in STEM fields, specifically IT, there are H-1Bs approved for a very wide variety of white-collar jobs including journalism, accounting, marketing, and in the medical field, etc. The key eligibility criterion is that a bachelor’s degree is typically the base-level educational attainment required to enter the occupation.

3. Patrick Thibodeau, “Southern California Edison IT Workers ‘Beyond Furious’ over H-1B Replacements,” Computerworld, February 4, 2015.

4. Harichandan Arakali, “India’s Infosys Cleared In Southern California Edison Department of Labor Probe,” International Business Times, September 8, 2015.

5. HCL Technologies was formerly known as Hindustan Computers Limited. Its subsidiary HCL America operates in the United States.

6. United States of America, ex rel. Ralph Billington, Michael Aceves, and Sharon Dorman (Plaintiff) v. HCL Technologies LTD. and HCL America, INC. (Defendants). Fourth Amended Complaint for Violations of the False Claims Act. United States District Court for the District of Connecticut. Civil Action No. 3:19-CV-1185 (MPS).

7. HCL. “Guidelines for H1 nominations.” Exhibit 57. Case 3:19-cv-01185-MPS Document 48-57, filed September 7, 2021.

8. Ron Hira and Daniel Costa, “The H-1B Visa Program Remains the “Outsourcing Visa”: More than Half of the Top 30 H-1B Employers Were Outsourcing Firms,” Working Economics Blog (Economic Policy Institute), March 31, 2021.

9. For example, see Sam Harnett, “Outsourced: In a Twist, Some San Francisco IT Jobs Are Moving to India,” MPR News, December 28, 2016. Harnett profiles Hank Nguyen who had to train his H-1B replacement when the University of California outsourced his work to HCL: “Nguyen says he escaped to America in 1981 … taught himself about computers so he could get a job in the tech world … the surest way for him to have a stable middle-class life.” Additionally, government data show that only one-fourth of computer systems analysts (Standard Occupation Code #15-1211), one of the most common H-1B occupations, have a master’s degree or more education. A higher share of computer systems analysts have educational attainment that is less than a bachelor’s degree. See Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Table 5.3 Educational Attainment Distribution for Workers 25 Years and Older by Detailed Occupation, 2018-19,” last modified September 8, 2021 [accessed November 2021]. The classic book by Robert Zussman, Mechanics of the Middle Class (University of California, 1985) describes how many from working class backgrounds entered engineering and technology occupations because they were attracted by the possibility of improving their economic status and class.

10. Women account for 36% of computer systems analysts, a much higher share than their share of software developers, at 19%. African Americans account for 10% of computer systems analysts, higher than their 6% share of software developers. See Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey, Table 11. Employed Persons by Detailed Occupation, Sex, Race, and Hispanic or Latino Ethnicity,” last modified January 22, 2021 [accessed November 2021].

11. USCIS Office of Policy & Strategy, Policy Research Division, H-1B Authorized-to-Work Population Estimate, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, June 2020.