Part of the series Labor Day 2019: How Well Is the American Economy Working for Working People?

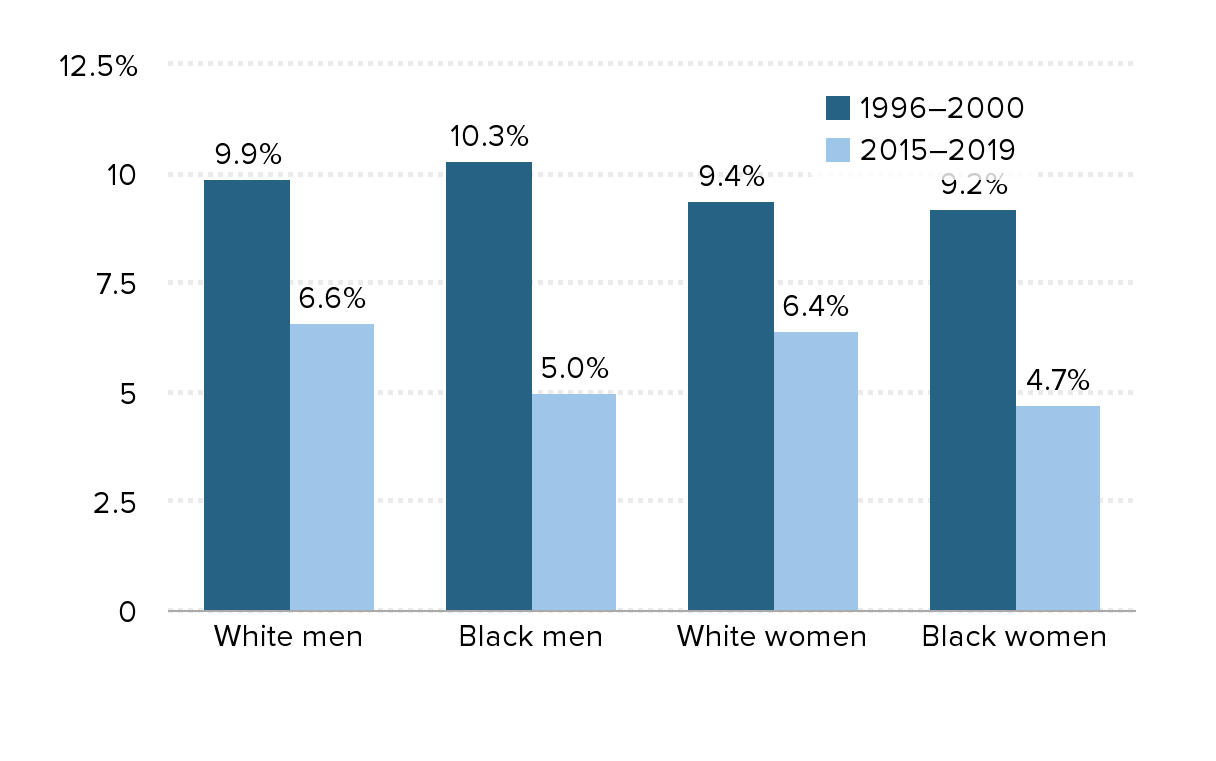

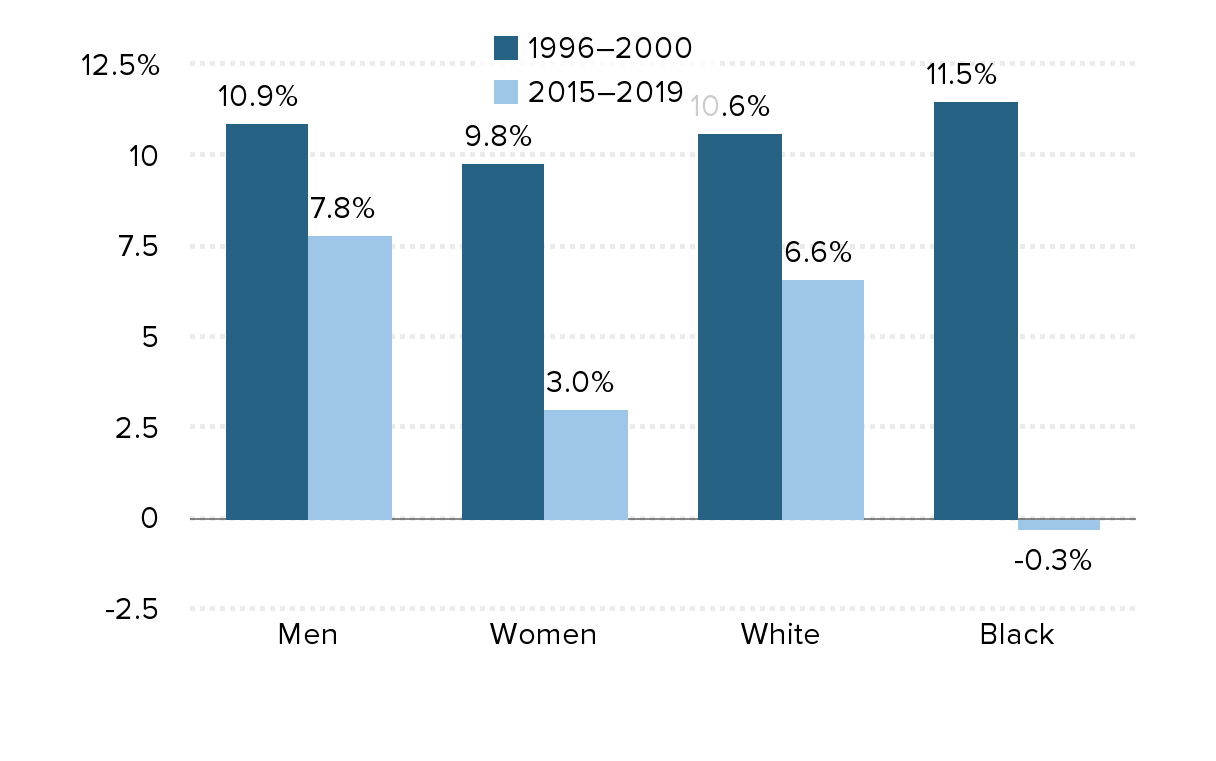

Summary: While unemployment rates in this recovery are similar to what we saw in the late 1990s recovery, wages have not grown nearly as fast or as evenly across race and gender as they did during that period. From 1996 to 2000, wage growth was above 9% for white men, white women, and black women, and was 10.3% for black men. But from 2015 to 2019, it was considerably slower for all groups, with growth slowing the most for black men and black women (to 5.0% and 4.7%). Wage growth gaps are even more dramatic among college graduates. From 2015 to 2019, women college grads saw their wages grow just 3.0%, compared with 7.8% for men, while wages of black college grads fell 0.3% versus 6.6% wage growth for white college grads. In contrast, wage growth for college graduates (like overall wage growth) was strong and even across all groups from 1996 to 2000—with black workers experiencing the strongest growth at 11.5% and other groups not far behind (10.9% for men, 9.8% for women, and 10.6% for white workers).

The Federal Reserve’s decision to lower interest rates by one quarter of one percent at the end of July sends an important message about the current state of the labor market. Nominal wage growth is nowhere near the level at which the Fed is seriously concerned about upward pressure on inflation. The lack of consistently strong wage growth is one of the remaining weaknesses of the labor market; nominal wage growth has stalled in 2019, even though the national unemployment rate has been at or below 4% for more than a year. The last time unemployment fell to 4% and below for an extended period of time—in the late 1990s—wage growth was much stronger across the board, as we describe below.

Wage growth overall is much weaker than it was in the late 1990s

Figure A compares rates of median wage growth over the five-year periods from 1996 to 2000 and 2015 to 2019, by race and gender. This chart shows that during the latter years of the 1990s, median wages grew by more than 9% for all groups shown—black and white men, as well as black and white women. Median wage growth overall was 8.9% from 1996 to 2000 and 5.9% from 2015 to 2019. (The overall numbers include data for racial/ethnic groups not represented in Figure A.)

Wage growth was stronger in the late 1990s than during the current expansion: Real median wage growth, 1996–2000 and 2015–2019

| 1996–2000 | 2015–2019 | |

|---|---|---|

| White men | 9.9% | 6.6% |

| Black men | 10.3% | 5.0% |

| White women | 9.4% | 6.4% |

| Black women | 9.2% | 4.7% |

Note: In order to include data from the first half of 2019, all years refer to the 12-month period ending in June.

Source: Authors’ analysis of Current Population Survey basic monthly microdata from the U.S. Census Bureau

While white men have seen the most wage growth between 2015 and 2019 (a cumulative 6.6%), even that pales in comparison with the lowest rate of growth seen by any group during the earlier period, between 1996 and 2000—which was 9.2% among black women. The last five years of the current recovery, when unemployment rates were closest to those during 1996–2000, has produced only a meager 4.7% increase in the median wage of black women, 5.0% among black men, and 6.4% among white women.

Based on the last 12 months of data (July 2018–June 2019), white men have the highest median wage at $23.31, followed by $18.98 for white women, $16.73 for black men, and $15.03 for black women. This means that the typical black woman is paid 36% less than the typical white man; for a full-time worker, this translates into $17,000 dollars less per year.1

Racial and gender wage gaps are wider than they were in the late 1990s—particularly among college graduates

As implied in the above data, the relatively slow and uneven wage growth that has characterized the longest economic expansion in history has also served to widen racial and gender wage gaps. One of the most troubling aspects of this trend has been the widening of wage gaps among college graduates. In fact, at a time when the unemployment rate suggests the labor market is perhaps as strong as ever, the most highly educated black workers are not reaping the benefits of economic growth.

Overall, real average wage growth for workers with a bachelor’s degree was 10.3% from 1996 to 2000 and 5.5% from 2015 to 2019. The 10.3% growth of the late 1990s was shared relatively evenly among men and women, and among black and white workers, as seen in Figure B. However, the much lower 5.5% growth rate over the most recent five-year period was not shared evenly at all. Over the last five years the racial wage gap among college graduates has widened as a result of declining wages among black college graduates (-0.3%) and rising wages among white college graduates (6.6%). By comparison, between 1996 and 2000, wages of black and white college graduates grew by 11.5% and 10.6%, respectively. Currently, the average wage for black college graduates is $27.32, compared with $35.37 for white college graduates.

Wage growth was stronger among workers with a bachelor's degree in the late 1990s than during the current expansion: Real average wage growth, workers with a bachelor's degree, 1996–2000 and 2015–2019

| 1996–2000 | 2015–2019 | |

|---|---|---|

| Men | 10.9% | 7.8% |

| Women | 9.8% | 3.0% |

| White | 10.6% | 6.6% |

| Black | 11.5% | -0.3% |

Note: In order to include data from the first half of 2019, all years refer to the 12-month period ending in June. Sample includes workers with a bachelor’s degree only.

Source: Authors’ analysis of Current Population Survey basic monthly microdata from the U.S. Census Bureau

Similarly, college wages have grown unevenly by gender. Between 2015 and 2019, college-educated women have seen their wages grow by only 3.0%, compared with 7.8% among college-educated men. The corresponding rate of growth for 1996 to 2000 was 9.8% among women with college degrees and 10.9% among men. The average wage for college-educated women is $28.77, compared with $39.47 for college-educated men. For full-time workers, this translates into over $22,000 in lower pay for college-educated women.

Conclusion

While this recovery has exhibited unemployment rates similar to what we saw in the late 1990s and 2000, the former period was characterized by stronger and more broad-based growth. Even among those with a college degree, wage growth over the last five years has been weaker and more uneven, increasing gaps between men and women and black and white workers.

Endnote

1. All data points in this report are derived from authors’ analysis of Current Population Survey basic monthly microdata from the U.S. Census Bureau.