Issue Brief #326

In 2011, New Hampshire legislators spent several months debating so-called “right-to-work” (RTW) legislation. To inform the discussion, the Economic Policy Institute issued a study that found that RTW has failed as an economic development strategy and is particularly unsuited to New Hampshire (Lafer 2011).

This report seeks to update legislators revisiting the RTW question on the evidence published since the last report. The new evidence strengthens the earlier findings: A right-to-work law could lower New Hampshire workers’ wages, reduce benefits, and threaten the state’s small business and health care sectors while doing nothing to boost job growth.

Recap: What the evidence showed in 2011

EPI’s 2011 report, Right to Work: Wrong for New Hampshire, noted that in states that have adopted RTW, annual wages and benefits are about $1,500 lower than for comparable workers in non-RTW states—for both union and nonunion workers—and the odds of getting health insurance or a pension through one’s job are also lower. The report also pointed out that RTW has no impact at all on job growth—a conclusion of multiple statistical studies carried out both by the report’s author and by other independent economists.

To a large extent, globalization has rendered RTW impotent, the report noted. In the 1970s and ’80s, U.S. companies may have moved to RTW states in search of lower wages. But in the globalized economy—the terms of which were ushered in by the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994—companies looking for cheap labor are overwhelmingly looking to set up operations in China or Mexico, not South Carolina.

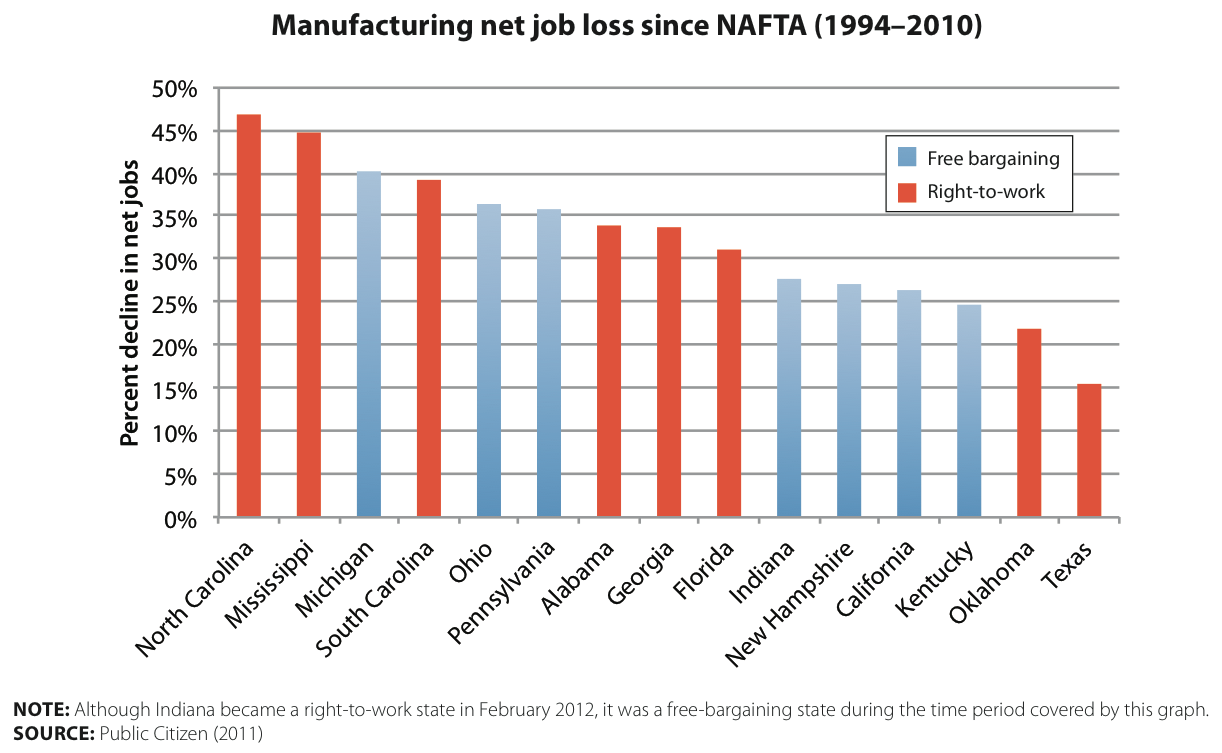

Every U.S. state has lost manufacturing jobs to cheaper labor overseas, and RTW laws have been powerless to prevent this. Indeed, as shown in Figure A, the RTW states of North and South Carolina, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida have all lost a higher share of their manufacturing sector since NAFTA than has New Hampshire (Public Citizen 2011).

In this sense, the most instructive case study for any state considering RTW in 2012 is Oklahoma, the only state to have newly adopted RTW since NAFTA took effect, the report said.

During the debate leading up to the passage of RTW in 2001, numerous corporate location consultants told Oklahoma legislators that the state was being “redlined” because up to 90 percent of relocating companies “won’t even consider” locating in a non-RTW location. If Oklahoma adopted RTW, the state would see “eight to ten times as many prospects,” these consultants promised (Lafer and Allegretto 2011).

But instead of growing, the number of new companies coming into Oklahoma has fallen by one-third in the 10 years since Oklahoma adopted RTW. Employer surveys confirm that RTW is not a significant draw. In 2009, manufacturers ranked RTW 14th among factors affecting location decisions (Gambale 2009). For higher-tech, higher-wage employers, nine of the 10 most-favored states are non-RTW. New Hampshire ranks 11th on that list, ahead of 21 of the 22 states that had RTW laws at the time (Atkinson and Andes 2010). (Indiana passed RTW in February 2012.)

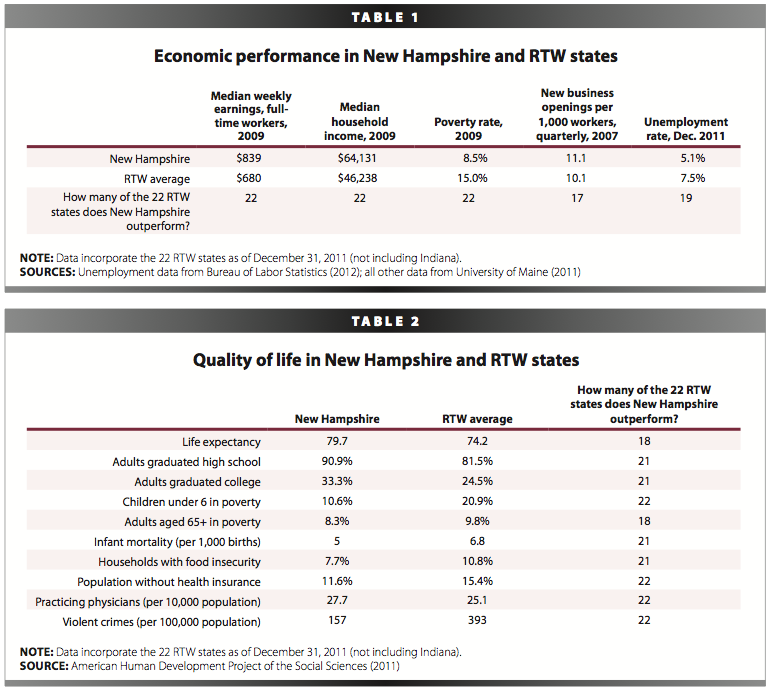

In addition, the 2011 EPI report found that New Hampshire’s economy is far superior to the average of right-to-work states (as shown in Table 1). Proponents of a right-to-work law claim that it is needed to bring new jobs into the state. But New Hampshire has already seen significant growth in the number of new companies incorporating in the state, including both local startups and out-of-state companies opening locations in New Hampshire. The number of businesses newly incorporated in New Hampshire increased by 60 percent from 2006 to 2009. Even more dramatically, the number of out-of-state corporations newly locating in New Hampshire rose by almost 150 percent over the same period (New Hampshire Employment Security, Economic and Labor Market Information Bureau 2011). Most tellingly, the number of new companies opening per 1,000 workers is higher in New Hampshire than in more than three-fourths of the right-to-work states. Even the conservative Tax Foundation declared in 2010 that “New Hampshire is a magnet for people and income,” noting that in all but one of the last 15 years, “New Hampshire has gained citizens at the expense of all other states” (Hodge 2009).

Partly due to its economic success, New Hampshire’s quality of life is far superior to that in the pre-2012 RTW states (as shown in Table 2), the report notes. In 2010, New Hampshire ranked among the top 10 states in the country in median household income; share of population with health insurance; share of population receiving dental care; number of primary-care physicians; low incidence of violent crime; and low incidence of heart attacks, strokes, infectious diseases, diabetes, low-birth-weight babies, and occupational fatalities (New Hampshire Employment Security, Economic and Labor Market Information Bureau 2011).

New Hampshire’s school system performs above national standards, with math and reading scores significantly above the national average in 2009 (New Hampshire Employment Security, Economic and Labor Market Information Bureau 2011). The median weekly earnings of New Hampshire workers are not only higher than the average of RTW states, but higher than in every single one of the RTW states. So too, is New Hampshire’s median household income higher, and its poverty rate lower, than in all of the 22 states with right-to-work laws prior to 2012 (University of Maine 2011).

For all these reasons, last year’s EPI report concluded that New Hampshire would do far better maintaining its existing law rather than imitating the RTW states.

What the new evidence shows

Significant new information since the last report confirms that RTW legislation is harmful:

- Independent economists confirm that RTW lowers wages for nonunion workers. A new study by a team of economists from the University of Nevada and Claremont McKenna College (Eren and Ozbeklik 2012) estimates that the damage that RTW inflicts on nonunion employees is even greater than earlier research suggested. The authors estimate that wages of nonunion workers in Oklahoma fell 4.3 percent as a result of RTW. The wage losses of nonunion workers could even be higher in states such as New Hampshire, where a higher share of the workforce is unionized than in Oklahoma.

- Employers say RTW is less meaningful than ever. In the past year, Area Development magazine updated its annual survey of manufacturers—focused on small manufacturers, which make up roughly three-fourths of the survey sample. RTW, which had never ranked in the top 10 factors influencing location decisions, ranked 14th in 2009 and slipped to 16th in 2010 (Area Development 2011).

- Oklahoma think tank reports that RTW has failed to create the predicted jobs. The Oklahoma Council on Public Affairs, a think tank that played a leading role in promoting Oklahoma’s RTW law, reports that the state has lost manufacturing jobs (Moody and Warcholik 2011) and become a net job exporter (Moody and Warcholik 2010), with jobs leaving the state to almost all of Oklahoma’s neighbors, including non-RTW Colorado.

- Study shows RTW increases construction fatalities. A new study shows that, in addition to its negative impact on wages and benefits, RTW also makes for less-safe workplaces, including increased fatalities for construction workers (Zullo 2011). This fact is unsurprising given that unions spend significant resources on occupational safety and negotiate job safety procedures beyond those contained in OSHA regulations. Since both the stated goal and the clear impact of RTW are to undermine union strength, it is only logical that job safety would suffer as a result.

- Data show New Hampshire continues to outperform RTW states. As of December 2011, unemployment in New Hampshire was lower than in all but three of the 22 states that had right-to-work laws at that time (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2012).

- Signs of weakness appear in the “South Carolina model.” Both the American Legislative Exchange Council (Laffer, Moore, and Williams 2011) and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce (Eisenach et al. 2011) issued reports promoting South Carolina as a model of economic development due, in part, to its RTW law, with the Chamber praising the Palmetto State for its “strong pro-employment policies” (Eisenach et al. 2011, 11). But at the end of 2011, South Carolina’s unemployment rate was 9.5 percent—nearly double that of New Hampshire. South Carolina’s poverty rate was also double that of New Hampshire, while its median household income in 2010 was almost $25,000 lower. The rate of new business openings was 25 percent greater in New Hampshire than in South Carolina. When it comes to “new economy” firms—the high-tech, high-wage employers that every state seeks—New Hampshire is ranked the 11th most attractive in the country, while South Carolina ranks 39th.

What misleading claims on behalf of RTW fail to show

The past year also produced evidence that sheds light on several highly misleading claims that have been put forth on behalf of RTW:

- Job growth in Texas was entirely in the public sector, unrelated to RTW. In its Rich States, Poor States report, the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) noted that RTW Texas has added more jobs in the past decade than any other state, declaring Texas “the state with the best policy to emulate” (Laffer, Moore, and Williams 2011, 13). What ALEC didn’t tell readers is that for the last four years, the state’s job growth has come entirely through government jobs, while the private sector shrank—clearly a trend that cannot be credited to RTW (Fletcher 2011).

- Claims that RTW influences corporate location decisions were based on 37-year-old evidence. A 2011 PowerPoint presentation by The National Right to Work Committee quotes an executive of Fantus, a site-location firm, warning that “approximately 50 percent of our clients … do not want to consider locations unless they are in right-to-work states” (National Right to Work Committee 2011). The committee neglected to mention that the quote comes from a 1975 report, and that by 1986, the firm’s executive vice president reported that the figure had fallen to 10 percent (Warren 1986).

- Population growth is unrelated to labor laws. ALEC’s report argued that faster population growth in the 22 states with RTW laws at that time showed that “people … want to move to places where workers have the freedom to decide whether they would like to join a union” (Laffer, Moore, and Williams 2011, 13). But national data show that most people move from one state to another to find more-affordable housing, to meet certain family needs, to retire, to move to or from college, to access better weather, or for other reasons unrelated to work (Schachter 2001; Molloy, Smith, and Wozniak 2010). There is no evidence that Americans move because of labor laws. In Texas, the largest RTW state, population growth was driven by “retirees in search of warm winters [and] middle-class Mexicans in search of a safer life,” explains Paul Krugman (2011), a winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics and columnist with the New York Times. Indeed, Texas experienced a greater influx of undocumented workers than any other state over the past decade (Pew Hispanic Center 2011). None of these dynamics is related to RTW.

Fifty years ago, Martin Luther King Jr. warned against “false slogans such as ‘right to work’…[whose] purpose is to destroy labor unions and the freedom of collective bargaining by which unions have improved wages and working conditions of everyone” (Economic Policy Institute 2012). His advice remains as timely today as when it was uttered— particularly for states like New Hampshire that have already charted a more successful path to economic growth.

—Gordon Lafer is an associate professor at the Labor Education and Research Center at the University of Oregon. His work concentrates on labor law and employment policy issues.

References

American Human Development Project of the Social Sciences. 2011. HD Index and Supplemental Indicators by State, 2010–2011 Dataset.

Atkinson, Robert D. and Scott Andes. 2010. The 2010 State New Economy Index, Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, November 2010, accessed January 27, 2011 at http://www.kauffman.org/uploadedfiles/snei_2010_report.pdf.

Area Development. 2011. “25th Annual Corporate Survey, 2010,” accessed December 1, 2011 at www.areadevelopment-digital.com/CorporateConsultsSurvey/25thAnnualCorporateSurvey.

Economic Policy Institute. 2012. Quick Takes. “Martin Luther King on ‘Right to Work.’” Accessed January 20, 2012 at http://www.epi.org/publication/martin_luther_king_on_right_to_work.

Eisenach, Jeffrey, David S. Baffa, Dana Howells, Richard Lapp, Camile Olson, Alexander Passantino, and Leon Sequeira. 2011. The Impact of State Employment Policies on Job Growth: A 50-State Review. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

Eren, Ozkan and Serkan Ozbeklik. 2012. “Union Threat and Nonunion Wages: Evidence from the Case Study of Oklahoma,” forthcoming working paper.

Fletcher, Michael. 2011. “Perry Criticizes Government While Texas Job Growth Benefits from It.” Washington Post, August 20.

Gambale, Geraldine, editor. 2009. The 24th Annual Corporate Survey, 2009, Area Development magazine, accessed January 21, 2011 at www. areadevelopment-digital.com/CorporateConsultsSurvey/24thAnnualCorporateSurvey#pg1.

Hodge, Scott A. 2009. “Taxes, Competitiveness, and the New Hampshire Business Climate.” Testimony of Scott A. Hodge, president of the Tax Foundation, before the New Hampshire House of Representatives, Ways and Means Committee. http://www.taxfoundation.org/files/sb_nh_2009.pdf

Krugman, Paul. 2011. “The Texas Unmiracle,” New York Times. August 14.

Lafer, Gordon and Sylvia Allegretto. 2011. Does Right-to-Work Create Jobs: Answers from Oklahoma. Economic Policy Institute Briefing Paper #300. Washington, D.C.: EPI.

Lafer, Gordon. 2011. ‘Right-to-Work’: Wrong for New Hampshire. Economic Policy Institute Briefing Paper #307. Washington, D.C.: EPI.

Laffer, Arthur B., Stephen Moore, and Jonathan Williams. 2011. Rich States, Poor States: ALEC-Laffer State Economic Competitiveness Index, 4th Edition. Washington, D.C.: American Legislative Exchange Council.

Molloy, Raven, Christopher L. Smith, and Abigail Wozniak. 2010. “Internal Migration in the US: Updated Facts and Recent Trends.” Accessed December 12, 2011 at http://www.nd.edu/~awaggone/papers/migration-msw.pdf.

Moody, J. Scott and Wendy P. Warcholik. 2010. “Moving In or Moving Out? A Look at Oklahoma Business Relocations,” Perspective. Oklahoma City: Oklahoma Council on Public Affairs.

Moody, J. Scott and Wendy P. Warcholik. 2011. Oklahoma’s Improved Performance Suggests Right to Work is Working. Oklahoma City: Oklahoma Council on Public Affairs.

National Right to Work Committee. 2011. “Indiana and Right to Work.” PowerPoint presentation, November 21, 2011.

New Hampshire Employment Security, Economic and Labor Market Information Bureau. 2011. Vital Signs 2011: Economic & Social Indicators in New Hampshire, 2006-09, February.

Pew Hispanic Center. 2011. “Unauthorized Immigrant Population: National and State Trends, 2010.” Accessed December 1, 2011 at www.pewhispanic.org/2011/02/01/iv-state- settlement-patterns.

Public Citizen. 2011. “Trade-Related Job Loss by State.” Accessed August 23 at www.citizen.org/ Page.aspx?pid=2543.

Schachter, James. 2001. “Why People Move: Exploring the March 2000 Current Population Survey,” Current Population Reports, U.S. Census Bureau, May.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2012. Local Area Unemployment Statistics. “Current Unemployment Rates for States and Historical Highs/Lows, Seasonally Adjusted,” Last modified and accessed January 2012 at http://www.bls.gov/web/laus/lauhsthl.htm.

University of Maine, Division of Lifelong Learning, Bureau of Labor Education. 2011. The Truth About “Right to Work” Laws, February. http://dll.umaine.edu/ble/RighttoWork_Laws.pdf.

Warren, James. 1986. “High Noon For Antiunion Law: Idaho Referendum On Right-to-Work Pits Labor, Right.” Chicago Tribune, September 25. http://articles.chicagotribune. com/1986-09-25/news/8603110671_1_afl-cio-work- committee-idaho

Zullo, Roland. 2010. Right-to-Work Laws and Fatalities in Construction, Institute for Research on Labor, Employment, and the Economy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.