Care work is vital to individual, household, and economic stability. Unfortunately, this highly demanded and demanding work is deeply undervalued and undercompensated. The care workers who allow those in their care—and their families—to flourish are paid persistently low wages with few employer benefits.

In this report, we focus specifically on two occupations in the care industry: early child care and education (“child care”) and home health care. The workers in these two occupations are overwhelmingly women and disproportionately Black, Hispanic, and Asian American/Pacific Islander (AAPI) women and immigrant women. Systemic racism, sexism, ableism, and xenophobia, in the form of labor market discrimination and occupational segregation, mean that these essential workers have little bargaining power, resulting in average wages half the amount of average wages for the workforce as a whole.

By the numbers

Child care and home health care workers, and care work as a whole, are deeply undervalued and underpaid, in part because of historical racism, sexism, and xenophobia that persist today.

- Wages: On average, child care workers in the U.S. are paid $13.51/hour and home health care workers are paid $13.81/hour—roughly half what the average U.S. worker is paid ($27.31).

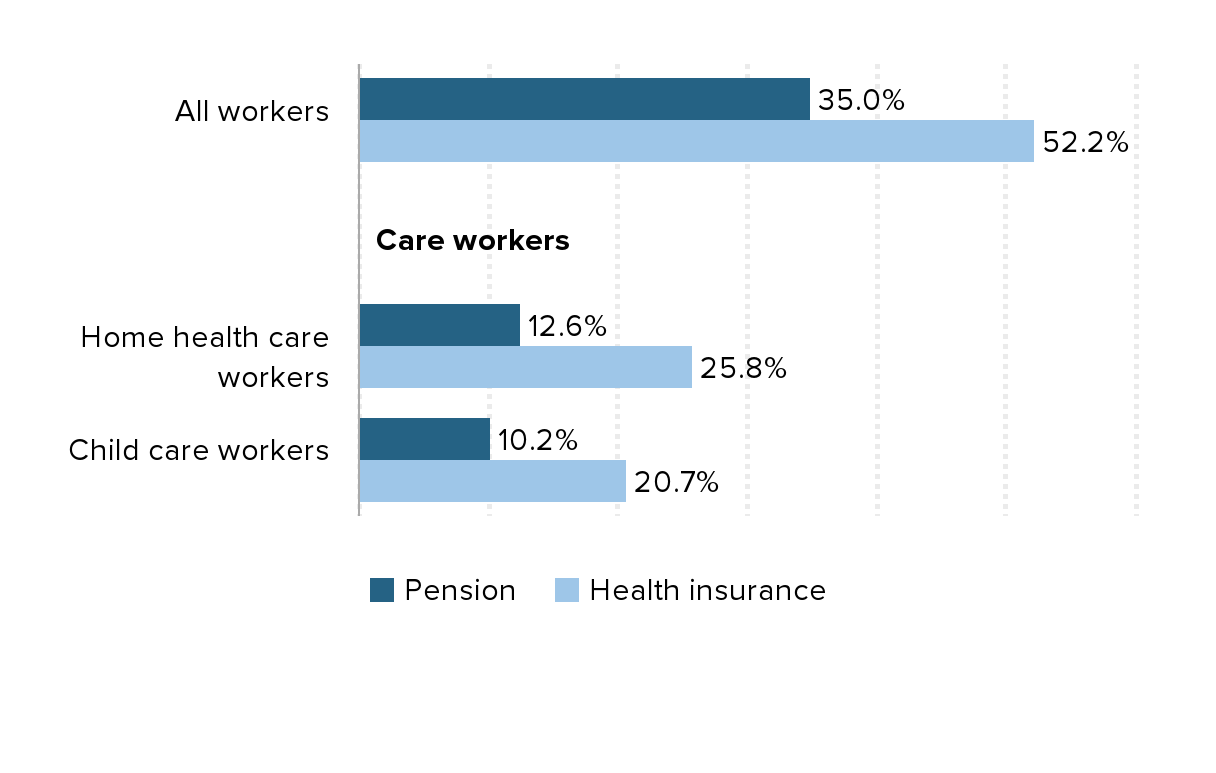

- Benefits: While 52.2% of all workers have employer-sponsored health coverage, only 25.8% of home health care workers and only 20.7% of child care workers do.

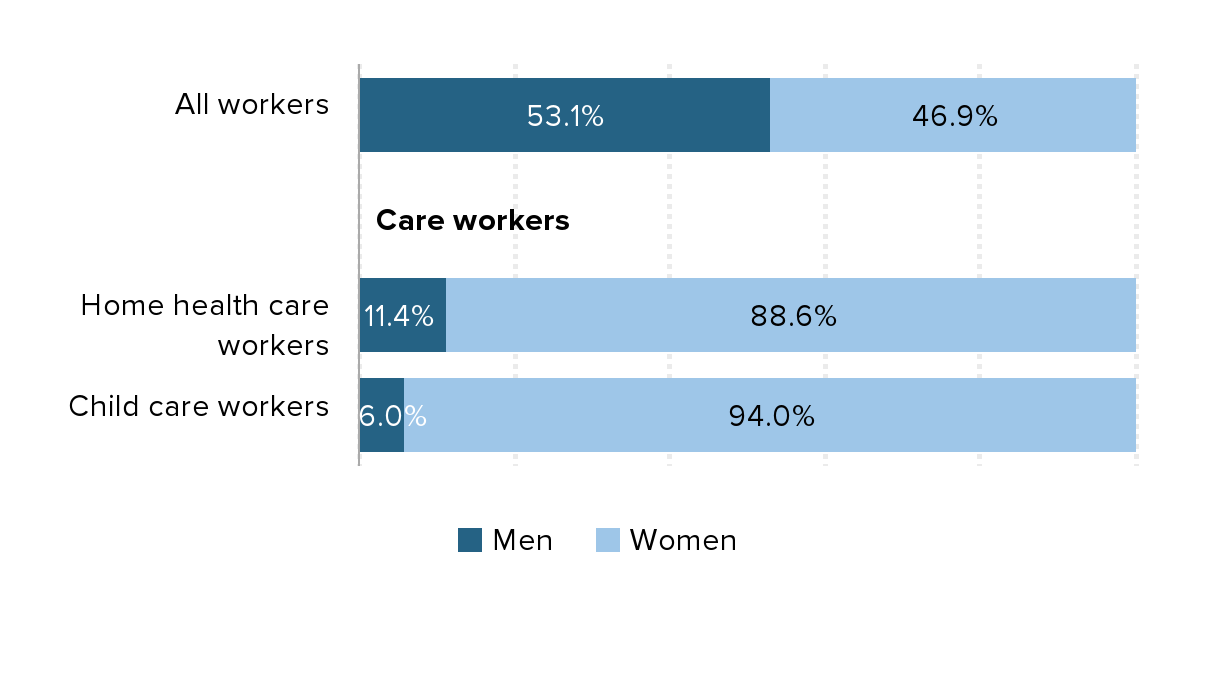

- Gender: Women make up 88.6% of the home health care workforce and 94.0% of the child care workforce.

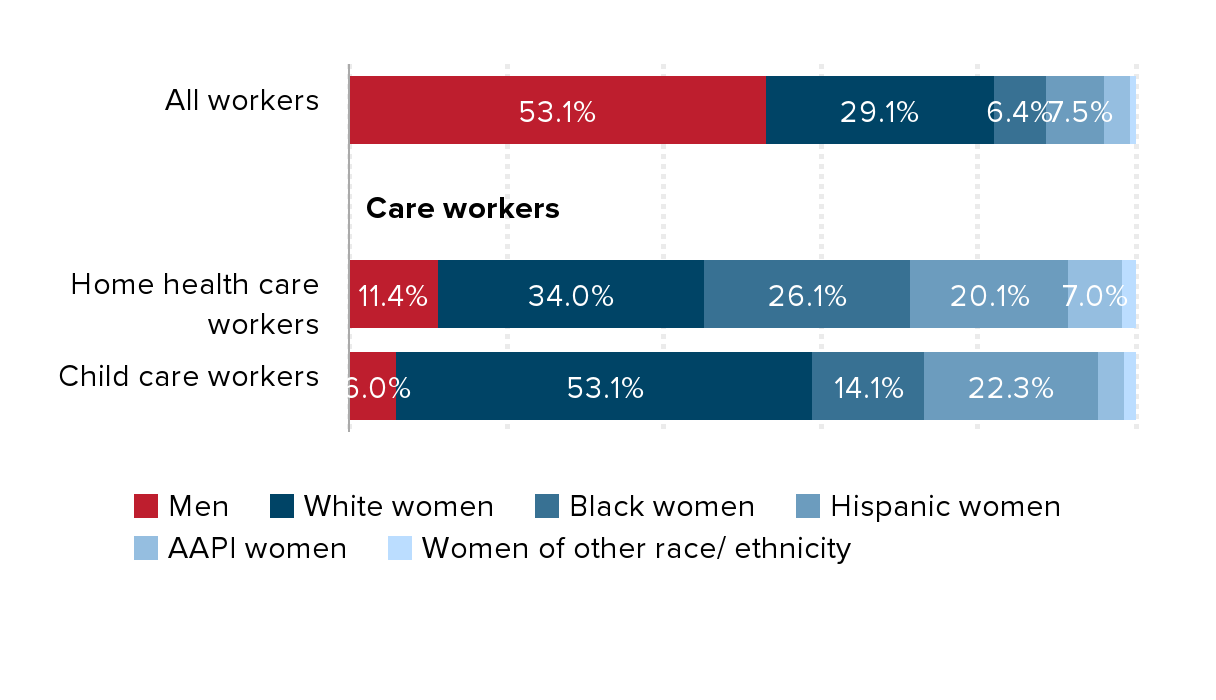

- Race/ethnicity: Women of color make up 17.8% of the workforce overall but 54.6% of the home health care workforce and 40.9% of the child care workforce.

How much should care workers be paid? We find that care workers should be paid, at minimum, an hourly wage between $21.11 and $25.95, depending on the benchmark applied.

The 2020 pandemic and recession laid bare just how inefficient and cruel the existing care system is. It is unaffordable for many families—including the families of care workers themselves—while simultaneously stranding many care workers in poverty. Given the high-contact, personal nature of care work, child care and home health care workers were among the workers most impacted when public health concerns forced shut schools, day cares, and businesses. The impacts of the recession—including income loss and large shares of women having to leave the workforce to manage caregiving responsibilities at home—left care workers in even more financial insecurity and stress than they were already facing.

While policymakers and the administration have recognized the urgent need to pay care workers more equitable and sustainable wages, determining a fair wage standard presents some challenges. This report builds a framework for thinking about how to set higher wages for care workers. As noted above, we focus our analysis on workers within two occupations in the care industry: child care, also referred to as early child care and education (ECE), and home health care.

First, we discuss the historical and ongoing systems of oppression that have influenced the development of the care sector, and we provide an overview of who care workers are in terms of demographics. These are some of our key findings:

- The development of the care sector and disparities within the care sector are fundamentally intertwined with historical and current ableism, sexism, xenophobia, and racism. Globally and in the U.S., care work has been devalued as “women’s work” and is primarily performed by women who face discrimination across other identities, such as immigrant and/or Black and Hispanic women. The devaluation of care work itself, along with the additional layers of discrimination many care workers face, in turn influence and perpetuate low wages and poor conditions in this industry.

- The average wage for early care and education workers and home health care workers is $13.51 and $13.81, respectively—about half the economywide average hourly wage. For a full-time worker, this translates to less than $30,000 a year.

- Care workers are less likely to receive nonwage benefits than the workforce as a whole: Over half of workers overall have employer-sponsored health insurance, compared with one-fifth of child care workers and one-quarter of home health care workers. One-third of workers overall have retirement benefits compared with only about one in 10 child care workers and one in eight home health care workers.

- Child care workers are overwhelmingly women (94%) and disproportionately Black (15.6%, compared with 12.1% in the overall workforce) and Hispanic (23.6%, compared with 17.5% in the overall workforce).

- Similarly, home health care workers are also largely women (88.6%) and disproportionately Black (23.9%) and Hispanic (21.8%).

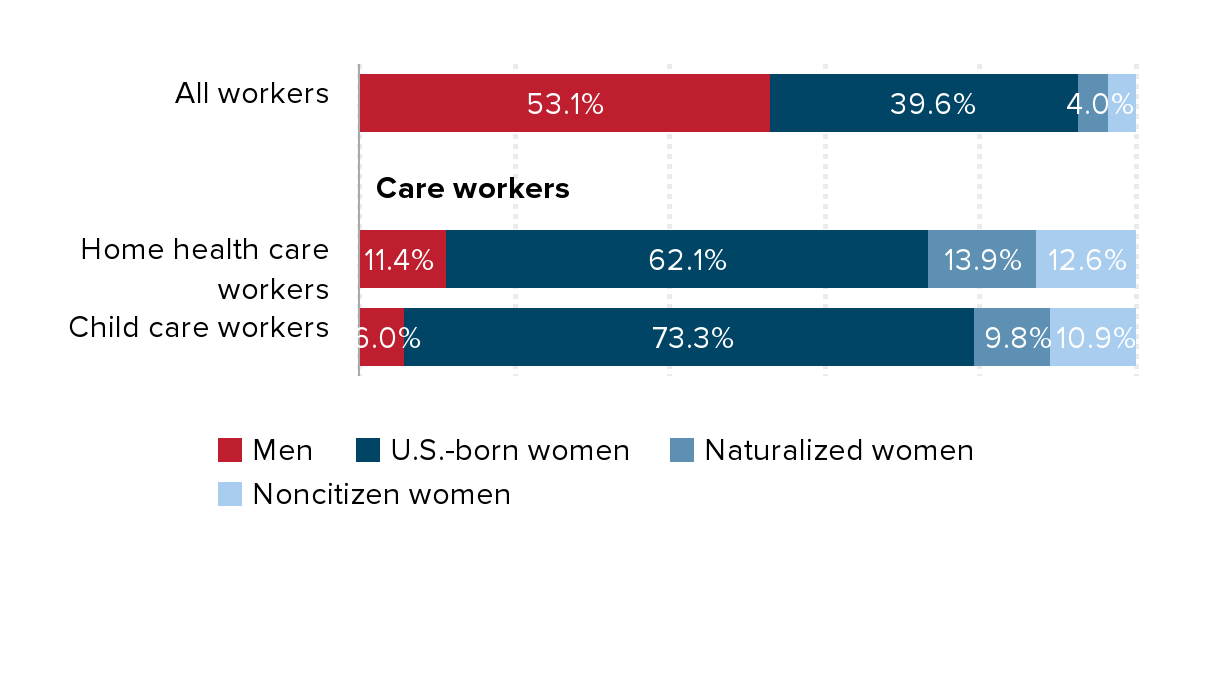

- More than one in five child care workers and roughly three in 10 home health care workers were born outside the U.S.

Building off existing literature on care work and pay penalties, we create and present a set of benchmarks for setting wages for child care and home health care workers. Key findings in our investigation of appropriate benchmarks include the following:

- A minimum standard for care workers is a wage that would allow them to support a young child on just their own wages in the least expensive metro area. We calculate this minimum living wage to be at least $21.11 per hour.

- A standard that reduces the penalty for doing care work; reduces the penalties care workers face because of gender, race/ethnicity, or on the basis of their citizenship status; and adds the premium they would receive if they were unionized, yields a wage starting point for home health care and child care workers of $22.26 and $21.90, respectively.

- Using our peer countries as models, not only for wage standards but also for standards of access to care, we find a wage benchmark for home health care workers of $25.95.

- Using other early educators as a model while reducing the pay penalties those early educators themselves face, we find child care workers should be paid at least $25.30.

- Higher wages must go hand in hand with other nonwage benefits such as paid leave, health insurance, and retirement benefits.

We conclude with an analysis of the economic costs incurred from the current care system and the economic benefits of paying higher wages:

- Higher wages would drastically improve care workers’ lives and financial security, allowing them to cover their costs (including the costs of care) more easily.

- Better pay translates into higher retention, lowered turnover, and increased possibility for recruitment, which all help employers as well as care workers, who bear the burden of short-staffing and constant change.

- Those receiving care, including people with disabilities, older adults, and children who are entrusted to care workers, would benefit from the stability of a more secure care workforce.

- Investing in early child care and education has been found to have a range of positive macroeconomic benefits, including a stimulus effect from increased spending by care workers; an increase in women’s labor force participation and parental earnings, as access to child care allows parents to reenter the workforce; increased earnings in adulthood for children who are in ECE programs, as well as intergenerational effects on their children; more jobs created; and a consistent positive impact on the economy.

Investing seriously and significantly in care infrastructure—in which higher wages for care workers is a key plank—would be transformative. Given that a public role already exists in this sector, the barriers to implementing this are not as steep as they would be otherwise. The foundation has already been laid. Given this foundation, policy action could have an especially positive and determinative effect on raising care wages.

Meaningful public involvement is not just a matter of more funding, but also of taking an active role to help enforce stronger labor protections and new wage standards. Many of our peer nations with better-functioning care sectors model a more comprehensive public role in which the state is involved in decisions about what care benefits will be made available to its residents in tandem with enforcing healthy working conditions and ensuring better compensation for care workers.

A greater public role in codifying and investing in higher care wages can make this sector and the U.S. economy as a whole fairer and more efficient. Raising care wages not only represents a critical opportunity, but it is also a long overdue moral responsibility. Care workers deserve to share in the economic security and happiness that their work helps to provide for millions of people.

Background on child care and home health care workers

Often called “the workforce behind the workforce,” care workers—whether those providing care to elderly or disabled adults or those providing early care and education to young children—are a vital pillar of our economy and society. Care workers are present in people’s lives every day and their work impacts nearly every person across the nation at one time or another. Care workers span many different occupations, have different qualifications, and have varied job responsibilities. While insufficient pay, benefits, and respect is pervasive across care jobs, it is important to recognize that the industry is not a monolith. This report focuses specifically on two vital care work professions: home health care and early child care and education.

Who are home health care workers?

Home health care workers can generally be split into two groups: those who are “agency-based”—paid through a Medicare-certified home health care agency, but working in clients’ homes—and those who are paid directly by clients (Wolfe et al. 2020). Over half of the funding for long-term direct care comes from Medicaid reimbursements (Campbell et al. 2021).

Home health care workers provide a range of personalized and client-specific supportive services to people with disabilities and elderly adults. Home health care is often the lynchpin that allows these clients to remain in their own homes and live as independently as possible, rather than having to move into a residential care facility (SEIU 775 and CAP 2021). Research has shown that home- and community-based care, of which home health care is a subset, also supports and alleviates the physical, emotional, and economic strain put on family caregivers (Women Effect Action Fund and NDWA 2021).

Home health care workers’ day-to-day work encompasses a wide range of physically demanding and deeply specialized tasks, including managing medication, grocery shopping, laundry, cooking, cleaning, helping clients with getting dressed or transported, and more. These are all life-enriching tasks that require strong communications skills as well as an intuitive awareness of client needs.

Who are child care workers?

We also examine early child care and education workers. Child care is funded through a range of sources, including government block grants such as the Child Care & Development Block Grant (CCDBG) program, Head Start, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), as well as financial payments from parents or other family members.

Like home health care work, early child care and education work is highly skilled and labor intensive. Child care work has long been devalued as just “looking after” children, when in reality, child care combines education with skill development and acquisition. As an early educator herself says, “We do more than teach, we build” (Boldin-Woods 2021). Child care workers are early educators who nurture, educate, foster developmental and language skills, and more.

The skills required to be successful early child care educators vary widely with the ages of those they are caring for, as each age group—from infant care through grade-school-aged children—requires different levels and methods of care. Care of very young children and infants can be physically and emotionally demanding.

Where does current funding come from?

The existing U.S. landscape for funding of care work is an interconnected web of different public funds combined with private pay, and the sources of funding vary widely by state and sector. Funding may come from means-tested public programs such as Medicaid or TANF, public universal benefits such as Medicare Advantage (for long-term care), private insurance, or private pay from parents and households (Campbell et al. 2021).

In some cases, the costs are borne more on one side: Estimates show that about 60% of child care costs are borne by parents and 40% are paid through various government sources (U.S. Treasury Department 2021; Oncken 2016). The funding system is especially complex given that within states there is much variation and recent experimentation with child care provision, from subsidy block grants to universal pre-K programs.

Separate measures of home- and community-based care show that 58% of these costs are funded through Medicaid (Campbell et al. 2021; Women Effect Action Fund and NDWA 2021). Exact breakdowns are hard to calculate, and it is likely many people use a mix of personal funds and funds from government programs such as Medicaid, the Child Tax Credit, TANF, and others. But the bureaucratic burden of applying for these funds, along with often unnecessarily stringent work and eligibility requirements, also means that many who should qualify for, and are in need of, these public funds do not receive them.

What is clear is that both child care and home health care have existing public funding pipelines and infrastructures. This preexisting public role means that there is strong potential for increasing the effectiveness of these systems through significant public investment (Gould and Blair 2020).

Public grant programs are one of the main ways households with lower incomes can access and afford child or elder care, so increasing funding for these programs (and thereby decreasing the cost burden from private, personal sources) is an equity issue. If we don’t make care more affordable through public investment, care will become increasingly unaffordable for these lower-income families (EPI 2020). Child care is also becoming increasingly unaffordable for middle-income families. And yet, despite being so expensive to access, the care industry is simultaneously unable to provide decent jobs to those doing this highly sought-after work. All of these concerns point to the need for increased government investment.

A strong public role can also ensure greater funding for enforcement of labor standards and working conditions. The care sector is notorious for workplace violations (as well as employee misclassification) leading to lowered or even stolen wages (Looman 2021).

Finally, it is important to note that higher government funding on its own does not always lead to equitable outcomes. Without safeguards and guidelines, states may misdirect or waste funds (Chappell 2020). Agencies must also enact provisions to ensure that federal funds actually reach the care workers themselves and not administrators or owners (CSCCE 2021).

The current economic situation of child care workers and home health care workers—a snapshot of low wages and benefits, poor working conditions, and little worker power—did not develop overnight or in a vacuum. Rather, the care landscape and resulting treatment of care workers is the result of a long history of devaluing care work and care workers.

Systems of oppression devalue care work and care workers

Care work allows humans to survive and thrive across generations. It encompasses tasks that can seldom be forgone or fulfilled without workers. Yet our societies and economic orders acutely undervalue care work and discredit how vital it is to our lives. This devaluation of care work is deeply rooted in ableism, sexism, xenophobia, and racism. We cannot remedy the precarity and immiserating wages associated with care work without acknowledging how these systems of discrimination shape the conditions of care work.

The gendered nature of care work

The undervaluation of care work—and of the people who predominantly shoulder care work—is a global phenomenon. Across the world, women do significantly more care work than men, both unpaid care work and in care occupations (Coffey et al. 2020; Addati et al. 2018; Connelly and Kongar 2017). Within the paid care sectors, women make up two-thirds of the workforce globally (Coffey et al. 2020). In the United States, the vast majority of care workers are women, as shown in Figure A. While women make up 46.9% of the entire workforce, they make up 88.6% of the home health care workforce and 94.0% of the child care workforce. On the whole, women are overrepresented twofold among care workers relative to their share in the overall U.S. workforce.

Care workers are disproportionately women: Gender breakdown of all workers, home health care workers, and child care workers

| Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|

| All workers | 53.1% | 46.9% |

| Home health care workers | 11.4% | 88.6% |

| Child care workers | 6.0% | 94.0% |

Note: To ensure sufficient sample sizes, this figure draws from pooled 2018–2020 microdata.

Source: Economic Policy Institute (EPI) analysis of Current Population Survey basic monthly microdata, EPI Current Population Survey Extracts, Version 1.0.18 (2021), https://microdata.epi.org.

There is an intrinsic connection between unpaid and paid care work. Care provision has historically been unpaid reproductive labor1 that women have done for generations, mostly within households, and without the dignity and valuation given to other work done in the productive structure of capitalist economies (Glenn 1992). Paid care work is the commodification of this work that has been traditionally treated as “women’s work” and given little to no status. Working conditions and low pay for paid care jobs reflect this, including the extent of scrutiny and suspicion regarding whether they are “skilled” jobs. Thus, care work in itself is treated as having little social value—and is therefore not well rewarded—despite how essential it is.

Through intense organizing efforts, advocates for care workers have sought to challenge these prevailing narratives and working conditions—and have made some headway (NDWA 2019). Unfortunately, workers in most care occupations still suffer from low wages, poor working conditions, and lack of dignity in the work they perform. However, the brunt of this is not equally felt. We see this when we further analyze the demographic breakdown of the care workforce below.

The gendered nature of care work is true for almost all occupations within the paid care industry: Care work is overwhelmingly performed by women. A select few care occupations, most notably doctors, break from these gendered and racialized trends, and these occupations have been able to secure prestige and higher pay, in part by limiting entry into these professions and setting strict education standards and licensing requirements. The ability for these handful of professions to attain and maintain leverage, along with the accompanying higher pay and prestige, are in themselves reflections of social hierarchies and power dynamics.

Historical racism and sexism underpin the composition of the care sector

Around the world, gender discrimination is compounded by discrimination based on other identities including race or ethnicity, class, and immigration status (Coffey et al. 2020). In the care workforce, we observe a concentration of workers who face discrimination across not just one, but across multiple identities: Not only is care work overwhelmingly performed by women in the U.S., but care work is also disproportionately performed by Black women and other women of color. And, as we discuss in the following section, many of these workers are immigrants (of varying statuses) as well.

The concentration of exploited groups in care occupations is part and parcel with the devaluation of care work as a profession. And the consequences of being subordinated across multiple identities reinforce and amplify one another and are reflected in the observed outcomes—low wages and poor working conditions—we see in the care industry.

Figure B expands on Figure A by disaggregating women into five groups by race and ethnicity: Hispanic women of any race, non-Hispanic white women, Black women, Asian American/Pacific Islander (AAPI) women, and women of another race. Compared with their shares in the workforce overall, Black, Hispanic, and AAPI women are far more likely to be home health care workers. In particular, Black women are more than four times as likely to be home health care workers relative to their shares in the workforce overall. Similarly, white, Black, and Hispanic women are overrepresented in the child care workforce.

Care workers are disproportionately women of color: Gender and race/ethnicity breakdown of all workers, home health care workers, and child care workers

| Men | White women | Black women | Hispanic women | AAPI women | Women of other race/ethnicity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All workers | 53.1% | 29.1% | 6.4% | 7.5% | 3.3% | 0.5% |

| Home health care workers | 11.4% | 34.0% | 26.1% | 20.1% | 7.0% | 1.4% |

| Child care workers | 6.0% | 53.1% | 14.1% | 22.3% | 3.3% | 1.2% |

Notes: To ensure sufficient sample sizes, this figure draws from pooled 2018–2020 microdata. AAPI refers to Asian American/Pacific Islander. Race/ethnicity categories are mutually exclusive (i.e., white non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, AAPI non-Hispanic, and Hispanic any race).

Source: Economic Policy Institute (EPI) analysis of Current Population Survey basic monthly microdata, EPI Current Population Survey Extracts, Version 1.0.18 (2021), https://microdata.epi.org.

Care work being predominantly borne by women of color dates back to slavery (Glenn 2012). In the second half of the 19th century and onward, Black, Mexican American, and Chinese American women served as inexpensive sources of labor in a growing market for workers to do the in-household care work that formerly enslaved people used to do (Glenn 1985; 1992). In the 20th century, care work became increasingly commodified in jobs outside the household as well. The composition of the resulting workforce was formed along both gender and racial lines, specifically at their intersection. The racial- and gender-motivated maltreatment of these workers translated into lack of protection and abysmal pay in these roles.

This racial- and gender-based discrimination had significant long-term structural, legislative, and policy impacts. For example, domestic workers were excluded from most New Deal reforms and denied access to unemployment insurance and other social insurance benefits provided to other workers (Wolfe et al. 2020; Edwards 2020). Only in 1974 were some private household domestic service workers incorporated under the Fair Labor Standards Act and made eligible to receive the federal minimum wage (Derenoncourt and Montialoux 2021). Unfortunately, Labor Department regulations issued shortly thereafter explicitly exempted “companionship” workers—those who serve as paid companions for elderly or disabled persons (NELP 2015). After fierce lobbying and organizing efforts, the rules were eventually broadened to include most home health care workers (Connolly 2015). The low (or no) wages, abysmal working conditions, and lack of empowerment in this industry that we still observe today are deeply entrenched in our history and economic framework.

Xenophobia shapes care workforces globally

Immigrants are frequently more concentrated in care professions relative to their shares in a country’s population or workforce. For some immigrants, language barriers, racism, and immigration status limit their employment opportunities and constrain them to take care jobs that are ill-paid and afford them little dignity as workers.

Immigrant workers are frequently overqualified for the care jobs they perform. Many have levels of education and advanced qualifications that are much higher than the qualifications required for their current jobs (Global Ageing Network and LTSS Center 2018). But medical degrees obtained elsewhere are often discredited or dismissed in their current country of residence—so if they want to use their training and continue doing health care in some form, these lower-paid care jobs become their only option.

Immigrants are disproportionately likely to be domestic care workers—working in people’s homes—facing especially precarious job circumstances. Globally, one in five paid domestic workers are migrants (Coffey et al. 2020). In the U.S., more than one in five child care workers and roughly three in 10 home health care workers were born outside the U.S.—either naturalized U.S. citizens, permanent residents, undocumented immigrants, or temporary migrant workers employed through “nonimmigrant” visas. As detailed in Figure C, while women who are naturalized U.S. citizens account for just 4% of the workforce overall, they make up 13.9% and 9.8% of the home health care and child care workforces, respectively.

Care workers are disproportionately immigrant women: Breakdown of all workers, home health care workers, and child care workers by gender and citizenship status

| Men | U.S.-born women | Naturalized women | Noncitizen women | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All workers | 53.1% | 39.6% | 4.0% | 3.3% |

| Home health care workers | 11.4% | 62.1% | 13.9% | 12.6% |

| Child care workers | 6.0% | 73.3% | 9.8% | 10.9% |

Source: Economic Policy Institute (EPI) analysis of Current Population Survey basic monthly microdata, EPI Current Population Survey Extracts, Version 1.0.18 (2021), https://microdata.epi.org.

This overrepresentation extends to noncitizens. There are a few “nonimmigrant” visas that allow U.S. employers to hire domestic workers or child care workers temporarily. These include a specific program under the B-1 business visitor visa, as well as A-3 and G-5 visas (Thrupkaew 2021). Perhaps the most well known is the State Department’s au pair program, which is part of the broader J-1 visa program for “cultural exchanges” (Costa 2019a).

In the United States, temporary work visa programs are employer-driven and rely on employer sponsorship (Costa and Martin 2018; Costa 2021). Workers on such visas typically have little power to negotiate for higher wages or better working conditions with their employers (Costa 2019b). These workers also often find it difficult to report abuses because of their dependency on their employer. The temporary work visas that facilitate employment of care workers have been associated with shocking scandals of worker abuse, exploitation, and forced labor (Kopplin 2017; ILRWG et al. 2018; Costa 2019a; Thrupkaew 2021).

In this way, the U.S. is not dissimilar to countries that are known to have particularly onerous immigration sponsorship programs, such as the kafala system found in Gulf Cooperation Council countries.2 In the kafala system, a worker’s immigration status is directly tied to their employer and they cannot seek another employment opportunity without their employer’s permission (Coffey et al. 2020; Addati et al. 2018). This makes domestic workers under such a system incredibly vulnerable and—as in the U.S.—discourages reporting of abuse.

All of this reinforces that a country’s immigration policies are a critical vehicle for securing a “high road” care economy and enforcing labor rights (Addati et al. 2018; Costa 2019b). Employer groups in the United States have prioritized new flows of temporary migrant workers to fill a range of occupations, including care work, and have recently litigated to remove the requirement that employers pay care workers on visas at least the state minimum wage (O’Neal 2021). Keeping immigration policy from being used by employer groups to degrade standards in the care industry is a near-term challenge that is worth highlighting.

Ableism further amplifies the devaluation of care work

Sexism, racism, and xenophobia are integrally tied to the devaluation of care work and of those who predominantly perform it. Ableism adds a further dimension to this devaluation by dehumanizing and devaluing two specific groups of people, namely disabled people and the elderly.

Altiraifi (2019, 3) defines ableism as “structural and interpersonal oppression experienced by people with disabilities or those presumed or determined to be disabled.” Relatedly, there is a social component to disability, in which “disability refers to a socially constructed system that categorizes, values, and ranks bodies and minds as normative or marginal” (Altiraifi 2019, 3). Thus, those who are dependent on care because of disability are not seen or treated as equal members of society and are marginalized based on how much they are viewed to contribute to the productive structure of the economy. Therefore, the labor rendered to provide the support and services they need is necessarily devalued. As a result, there is a close link between care workers and people with disabilities and older adults as subjects of an overlapping marginalization—and, indeed, for some care workers who are themselves disabled, this connection is even more profound (Chang 2017).

Ableist narratives and policies devalue and dehumanize people needing care in ways that are inextricably linked to the racialized systems of oppression that devalue care workers’ labor: The same ideologies that dehumanize and marginalize people with disabilities also exploit immigrant women of color and limit their options to precarious jobs (Chang 2017). Consequently, the fight for better working conditions and pay for care workers is inseparable from also centering and improving conditions for people with disabilities and older adults (Novack and Cokley 2020).

Wage benchmarks for care work

We’ve already established that care workers are undervalued and underpaid in the United States and across the world. Our objective in this section is to provide policymakers with a broad economic framework for thinking about how much care workers should be paid in the U.S. labor market. Using the research literature and microdata, we provide several considerations for setting pay standards for care workers, with specific estimates for home health care and child care workers. In Table 1, we present current wages and propose various benchmarks to reduce pay penalties and improve wages in these jobs. These benchmarks include the following:

- a minimum standard for a living wage for all workers;

- an estimated wage standard that (1) reduces wage penalties currently faced for performing care work; (2) reduces penalties associated with racial and gender discrimination; and (3) adds an estimated union wage premium for care workers;

- a standard for home health care workers based on international standards; and

- a standard for child care workers based on other early educators in the U.S. economy.

We also provide in this section a more detailed discussion for understanding the research basis and assumptions built into our benchmarks.

Proposed benchmarks for setting wage standards for care workers

| Home health care workers1 | Child care workers2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Current average wage | $13.81 | $13.51 |

| Economywide wage standards | ||

| Minimum wage | $15.00 | $15.00 |

| Living wage (least expensive U.S. metro area)3 | $21.11 | $21.11 |

| Reducing pay disparities | ||

| Reducing care penalties4 | $15.74 | $15.47 |

| Reducing demographic penalties5 | $20.20 | $19.87 |

| Add union premium6 | $22.26 | $21.90 |

| Adopt international standards | ||

| EU average7 | $21.85 | |

| Netherlands/Norway8 | $25.95 | |

| Adopt wages for other teacher professions | ||

| Education-adjusted elementary/middle school salaries9 | $21.22 | |

| Reducing teacher penalty10 | $25.30 |

Notes: Wages are based on pooled 2018–2020 microdata from the Economic Policy Institute’s extracts of the Current Population Survey, reported in 2020 dollars. See extended notes for methodology.

Wages are based on pooled 2018–2020 microdata from the Economic Policy Institute’s extracts of the Current Population Survey, reported in 2020 dollars. (1) Home health care workers are identified in EPI’s CPS extracts by the occupations nursing, psychiatric, and home health aides, and personal and home care aides and the industries private households, home health care services, individual and family services. (2) Child care workers are defined by the child care worker occupation. (3) The Brownsville/Harlingen metro area in Texas is the lowest cost metro area for one adult and one child, according the EPI’s Family Budget Calculator. We adjust the annual required budget for basic necessities for inflation to 2020 and divide by 2080 to reflect the required hourly wage to satisfy that family budget solely with full-time labor earnings. (4) We reduce the care penalties among care workers by applying the 15% penalty among women and 6% penalty among men from Budig, Hodges, and England (2019) proportionately to women and men in each care occupation. (5) We calculate demographic penalties in a log wage regression on interacted gender-race/ethnicity-citizenship status controlling for age, age squared, educational attainment, and geographic division. The statistically significant coefficients are then applied proportionately to the shares each demographic group is found in the relevant care occupation. (6) We apply the union premium of 10.2% as reported in this EPI factsheet. (7) Dubois (2021) reports that across the current 27 E.U. member states, non-residential long-term care workers are paid 80% of the average national hourly wage. (8) Dubois (2021) reports that across the current 27 E.U. member states, the best performers, Netherlands and Norway, are among the few who not only universal rights to provision of care services. They pay nonresidential long-term care workers 95% of average wages. (9) This procedure uses actual weekly earnings for elementary and middle school teachers by educational attainment from EPI’s CPS extracts and applies that to the educational attainment shares for child care workers to create weekly earnings of child care worker wages with a college or advanced degree. For educational attainments lower than a college degree, we apply the overall weekly earnings ratio of that level of educational attainment to the one needed. We apply the ratio of weekly earnings from child care workers to the imputed value to back out a child care hourly wage. (10) We apply the teacher pay penalty of 19.2% found in Allegretto and Mishel (2020).

Source: Economic Policy Institute (EPI) analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata, EPI Current Population Survey Extracts, Version 1.0.18 (2021), https://microdata.epi.org.

We begin by identifying and defining the workers we are looking at. To ensure sufficient sample sizes for average wages (as for the demographic analysis presented earlier), we pool three years of data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Current Population Survey, from 2018 to 2020 (EPI 2021a). We then identify home health care workers and child care workers by their respective relevant industries and occupations.3 Average wages are $13.81 for home health care workers and $13.51 for child care workers, in 2020 dollars.4 In contrast, the average worker wage economywide is $27.31 per hour.

Note that Table 1 proposes benchmarks for care worker wages only, not for total compensation or working standards. The reality is that, in addition to suffering from low wages, both child care and home health care workers are unlikely to receive nonwage benefits such as employer-sponsored health care coverage, pensions, or paid medical or family leave.

Figure D shows the shares of the workforce who have access to health insurance and pension coverage on the job (Flood et al. 2021). While just over half (52.2%) of all workers have an employer-sponsored health insurance plan that is at least partially paid for by their employer, only one-fifth (20.7%) of child care workers and one-quarter (25.8%) of home health care workers have that benefit.

Workers overall are less likely to have pension coverage (a pension plan or other retirement plan at work) than they are to have health insurance coverage: Just over one-third (35.0%) of the workforce has a workplace retirement plan. But an even smaller share of care workers have pension coverage: 10.2% of child care workers and 12.6% of home health care workers.

Home health care and child care workers are less likely to have employer-sponsored health insurance and pension coverage: Shares of all workers, home health care workers, and child care workers who have health insurance and pension coverage

| Pension | Health insurance | |

|---|---|---|

| All workers | 35.0% | 52.2% |

| Home health care workers | 12.6% | 25.8% |

| Child care workers | 10.2% | 20.7% |

Notes: Pension includes respondents who were included in their or employer’s pension plan or other retirement plan. Health insurance includes respondents whose employer paid for part or all of their cost of premiums for an employment-based group health insurance plan. Data are pooled for 2018–2020.

Source: Authors’ analysis of IPUMS Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement microdata.

In addition to setting higher wages for care workers, we must also work to ensure that they receive sufficient nonwage benefits, such as health coverage, a retirement plan, fair scheduling, and paid leave. Many child care and home health care workers, because they make such low wages and receive little to no additional employer support in terms of benefits, are forced to juggle multiple jobs and patch the gaps with public benefits programs such as Medicaid, housing assistance, energy assistance, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance (SNAP), Special Supplemental Nutrition for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), or cash assistance/TANF (Cooper 2016).

Economywide wage standards

The first set of benchmarks we propose for care worker pay is based on the goal of improving economywide wage standards.

Raising the minimum wage

A starting place for all workers should be no less than $15 an hour. A minimum wage of $15 would finally increase the real purchasing power of low-wage workers above the minimum of 50 years ago (Cooper, Mokhiber, and Zipperer 2021).

Raising the minimum wage to $15 per hour would benefit over 19 million essential and front-line workers, raise wages for one in three Black workers and one in four Hispanic workers, and help lift millions out of poverty (Cooper, Mokhiber, and Zipperer 2021). Furthermore, more than half a million child care workers and nearly 2 million home health care workers would benefit from a $15 minimum wage (Wolfe and Zipperer 2021a; Wolfe and Zipperer 2021b).

Determining a living wage floor

While setting a higher economywide minimum wage is an important and necessary first step, it is not the final goal. A full-time, full-year worker making $15 an hour cannot support a family at a decent standard of living anywhere in this country. To better assess the true cost of living, EPI’s Family Budget Calculator estimates area-specific incomes needed to cover basic expenses like housing, food, transportation, health care, taxes, and other necessities (Gould, Mokhiber, and Bryant 2018; EPI 2018). The Brownsville/Harlingen metro area in Texas is the lowest-cost metro area to live in, according to EPI’s Family Budget Calculator (EPI 2018), but even in this lowest-cost metro area, a worker trying to make ends meet for themselves and one young child on just their own wages would have to earn a full-time hourly wage of at least $21.11 (EPI 2018).5 A worker living in any other metro area in the country would of course need an even higher wage—a far higher wage in some areas—to attain a decent standard of living.

Even apart from the basic moral obligation to pay a living wage for a day’s work, there are good reasons that care workers should be paid substantially more than $15 for the work they do. Care workers do vital and demanding work. This work should be assigned a monetary compensation value that is more commensurate with its value to society. Care workers should be also compensated at a level appropriate to the demands of the work. Finally, in order to meet growing needs—and not leave large shares of the population stranded without needed care—we will ultimately have to pay wages and benefits at a level that will attract sufficient numbers of workers to meet the demand.6

Reducing pay disparities

As discussed above, pay inequities experienced by care workers have multiple root causes. Care work itself has been historically undervalued. Given that care workers are predominantly women, and disproportionately people of color and immigrants, they are also impacted by historical and current sexism, racism, and xenophobia and associated gender and racial/ethnic wage gaps. Further, care workers, like millions of other workers in our economy, have faced lower wages because of their lack of bargaining power in the labor market. In our second set of benchmarks, we examine the penalties these workers face for the work they do and for who they are, and we present an alternative pay proposal that reduces these barriers to higher pay.

Measuring the care penalty

A wide body of economic research has identified and measured a care penalty—that is, the lower pay received by care workers after controlling for characteristics of care jobs, skills required, or qualifications.

One of the foundational studies in care penalty research found that care workers faced a 5–6% penalty compared with similar workers in other fields (England, Budig, and Folbre 2002). While this study makes a significant contribution to the field, there is good reason to believe that these 2002 estimates understate the penalty faced by care workers both then and today.7

The latest research from Budig, Hodges, and England (2019) on this topic finds a significantly larger care penalty than the 2002 study. In the 2019 study, the authors usefully separate out the various care occupations to isolate the differential effect of those that require specific credentials—an educational degree, coursework, and/or special certification/licensing—from those that do not require such credentials.8 The authors identify child care workers, nursing aides, and health aides among the low-education/high-licensing fields and find a 15% pay penalty among women and a 6% penalty among men in these fields.

A more recent study from the Economic Policy Institute—which controls for key demographic characteristics including gender, race/ethnicity, age, education, and census division—finds that home health care workers experience a wage gap of 27–36% relative to similar workers who are not in care jobs (Wolfe et al. 2020).

While the penalties vary widely across these studies, the common thread is that care workers face a penalty for choosing care work. After reviewing these and the broader care penalty literature,9 we ultimately chose to rely on Budig, Hodges, and England’s 2019 findings—which are in the middle of the range of estimates, and which are based on methodology that attempts to tease out a causal effect—to build our benchmark for a wage that reduces the care penalty.

Reducing care penalties

To build our next set of benchmarks, we first apply the care penalties found in Budig, Hodges, and England’s 2019 analysis. To that end, we reverse out their 15% pay penalty for women and the 6% pay penalty for men in each care sector. Because of the hugely disproportionate number of women in both care sectors (as shown in Figure A), this equates to an overall pay penalty of about 14%. Starting with current care worker wages and then reducing care penalties by 14%, we find a benchmark for care wages to be $15.74 and $15.47 for home health care workers and child care workers, respectively.

Reducing demographic penalties

However, the penalty care workers face in the labor market is not limited to the fact that care work is largely undervalued and underpaid. The care pay penalty also exists because the population who does the work is undervalued. To better understand and address this dynamic, we must look more closely at who care workers are and the historical and social discriminations they have faced and still face today.

By the mere fact of their demographic characteristics, namely their gender, race, ethnicity, and citizenship status, many care workers have faced historical and current barriers to employment and equal pay. These demographic penalties reduce the outside options care workers have in the labor market, thus reducing their bargaining power or leverage to receive higher pay in their respective care-working professions. The additional penalty these workers face in the labor market at large needs to be taken into account when determining just how much care workers need to be paid to mitigate these effects.

To measure those demographic penalties, we use a multivariate regression model to tease out a reasonable estimate of the penalties workers face in the labor market based on their gender, race/ethnicity, and citizenship status, controlling for typical human capital measures like education and experience, which tend to impact wages.10 Then, we apply those demographic penalties to the shares of the workforce represented by each of those groups.11 Because these workers’ outside options are limited due to historical and current labor market discrimination, a fair wage must address all of these penalties. Reducing these measured demographic penalties, on top of the care penalty reductions we calculated above, yields a new benchmark wage of $20.20 for home health care workers and $19.87 for child care workers.

Adding a union premium

Reducing the care penalty and the demographic penalties are two necessary steps to improving care worker pay. Another important step is to harness the bargaining power that results from increased unionization to boost wages and working conditions in these industries. While a strong public sector plays a crucial role in both funding and labor enforcement, unions are another critical intermediary in negotiating and bargaining for higher pay and benefits.

A recent New York Times article, featuring the stories of two home health care workers in two different states, finds that home health care workers can face very different working situations depending on the presence of unions in their state: Home health care workers in states with high levels of union membership have higher wages and are more likely to have paid time off, medical and dental insurance, retirement benefits, and more, while home health care workers in states with low levels of unionization have lower wages and few to no benefits (Schulte and Robertson 2021).

The union premium is the additional pay unionized workers—workers who are either union members or covered under a union contract—receive relative to the pay of nonunionized workers. We estimate the union premium in a regression framework controlling for other individual and job characteristics, such as the worker’s education and employment sector. On average, workers covered by a union are paid 10.2% more in hourly wages than their nonunionized counterparts (EPI 2021b). Our analysis also shows that, in addition to having higher wages, unionized workers are more likely to have better benefits such as paid leave and health care, both of which are particularly crucial during a global pandemic (Gould 2020).

If care workers had leverage over their pay similar to that found from being in a union, care workers could reap a similar increase in pay (McNicholas et al. 2020). Applying this premium to care workers’ wages, on top of the care work penalty and demographic penalty reductions estimated above, wages for home health care and child care workers would be $22.26 and $21.90, respectively.

Adopting international standards for home health care workers

Around the world, care work is incredibly gendered and mostly performed by women who face additional forms of systemic oppression across identities such as ethnicity or race, class, and immigration status (Coffey et al. 2020). Despite the fact that the undervaluation of care work and the resulting difficulties in securing a stable care workforce are global phenomena, the situation for U.S. workers is particularly dismal when compared with peer countries.

The involvement of the state in both funding care provision and overseeing its workforce is the through line among nations with better-functioning care sectors. In a detailed examination of care work and its workforce, the International Labour Organization (ILO) concludes that “public provision of care services tends to improve the working conditions and pay of care workers and unregulated private provision to worsen them, regardless of the income level of the country” (Addati et al. 2018, 166). The ILO identifies Denmark, Finland, Norway, the Netherlands, and Sweden as a cluster of nations with very high levels of employment in the care sector. These nations have a number of things in common that inform their stronger care workforces. Among them is a universal right to access care services.

Applying the EU average wage for home health care workers

These conditions translate to significant benefits for care workers. Finland, for example, has one of the highest median hourly wages among OECD countries for care workers in the long-term-care sector (OECD 2020, Fig. 1.6). Another useful earnings statistic is the average hourly wage in various care sectors as a share of the national average hourly wage across the economy. Across the current 27 European Union (EU) member states, nonresidential (i.e., caring for a client in their home rather than in a residential care facility) long-term-care workers are paid 80% of the average national hourly wage. Extrapolating to the U.S. context using average hourly wages in the U.S. labor market, home health care workers would be paid $21.85 per hour using this benchmark.

Applying the top European wages for home health care workers

Among 29 countries analyzed—the 27 EU member states, plus Norway and the United Kingdom—the Netherlands and Norway were tied for the highest wage ratio (relative to the average national wage) for social services workers in the nonresidential long-term-care sector (i.e., the home health care sector), at 95% (Dubois 2021). Applying this 95% ratio to the U.S. context, we arrive at a benchmark of $25.95 for home health care wages.

Adopting child care wage standards based on other teaching professions

Early child care and education workers must have many of the same skill sets and expertise as elementary and middle school teachers. These care workers have a vital influence on children’s cognitive, social, and emotional development (Penn State 2011). While they are sometimes seen as akin to babysitters, these early educators in fact perform a role similar to that of other teachers of young school-age children. Therefore, they should be paid as much as similarly educated teachers of elementary and middle school teachers (McLean et al. 2021).

Applying education-adjusted elementary/middle school teacher salaries to child care workers

We begin creating this benchmark by estimating average weekly earnings for elementary and middle school teachers by educational attainment (EPI 2021a).12 We apply these earnings to child care workers based on their own level of educational attainment and on the share of child care workers with each level of education in five categories: less than high school, high school, some college, college, and advanced degree.13 We then return to a measure of hourly wages and find that a more fair wage standard, using this benchmark, would pay the average early child care and education worker $21.22 an hour.14

Reducing the teacher penalty

Unfortunately, elementary and middle school teachers themselves face substantial wage penalties in the labor market compared with similarly credentialed workers in the economy overall (Allegretto and Mishel 2020). Setting child care wages modeled only on teacher wages perpetuates the pay disparities teachers face and embeds those disparities into the child care pay standard. Therefore, we attempt to remove this pay penalty when setting our final wage standard for child care workers by reversing out the teacher pay penalty of 19.2% to the education-adjusted elementary and middle school pay standard (Allegretto and Mishel 2020). Removing the teaching penalty yields a reasonable wage standard of $25.30 for child care workers.

Benefits of paying workers more for care provision and quality

Care workers are severely underpaid, and, as outlined above, they face multiple pay penalties. Paying care workers more is not only possible and long overdue, but it would result in far-ranging positive consequences for those they care for and the macroeconomy. Along with providing much-needed financial stability and economic security to care workers themselves, higher wages in the care sector would produce a range of positive benefits to people with disabilities, older adults, and children; employers and institutions; and the economy as a whole.

To put it simply, raising wage standards for care workers makes good economic sense. The existing low-wage care system is highly precarious and inefficient, not to mention extremely harmful to care workers themselves. The persistent low wages and lack of benefits mean that many care workers cannot afford to support themselves or their families, and many leave or change jobs as a result. This high turnover, in turn, damages the quality of care provided and imposes costs on employers (Ruffini 2020; Caven et al. 2021; Batt, Lee, and Lakhani 2014). And the churn in general hurts the macroeconomy.

Providing much-needed financial stability and economic security to care workers

The inefficiency and dysfunction of the care economy imposes steep costs—not the least of which is the cost to care workers in lost and low wages. Higher wages would transform the lives of the care workers who are the foundation of the current system. Both child care workers and home health care workers carry out deeply specialized and often physically and emotionally demanding labor for poverty-level wages and without fringe benefits or paths for advancement. These care workers are deeply committed to the people in their care and recognize the risk their absence would pose to the well-being of people with disabilities, older adults, and children. And yet the devaluation of care work—combined with the sexism, racism, and xenophobia many of these workers endure—make it less likely that care workers will be treated with the respect they deserve. In addition, given the isolating nature of the job and physical distance from co-workers, it is harder for care workers to build solidarity, strike, or use other traditional levers of worker power to increase their pay or labor standards.

Long hours and low wages mean that, in reality, millions of care workers cannot afford to cover their family’s basic needs, especially as costs and rents have skyrocketed (Gupta 2021; Gould 2015; Mazzara 2019). Out of financial and economic necessity, many are forced to leave the care sector for other industries, which may compensate them more equitably for their experience and labor. Increasing wages in the care sector would finally compensate and value care workers’ labor closer to the level it deserves, and it would provide much-needed economic security to these workers. Higher wages would allow more care workers to continue working in these demanding and critical jobs.

Strengthening the provision and quality of care

In addition to the costs to care workers, there are costs to those receiving care under the current system. The provision and quality of care would undoubtedly be strengthened with higher wages across the care sector and the resulting lower turnover. People with disabilities, older adults, and children who are entrusted to care workers for significant periods of time would thus strongly gain from the better pay. In addition, accessible care also provides parents or other family members, especially women, a means to work or reenter the workforce.

Broadly, the economic stability from a good-paying care job and the absence of financial distress translates into a more secure and less stressed workforce. In the case of child care, research has shown that stability in who is giving care, and interactions with experienced caregivers, are beneficial for babies’ and toddlers’ learning and growth in the crucial early years of development (Ludden 2016). Other research has found that high-quality early care has long-lasting effects (Abbott 2021).

In home health care, higher pay and reduced turnover would allow people with disabilities and older adults to build strong and trusting relationships with their caregivers. A recent economic study of the long-term residential care sector found that a 10% increase in the minimum wage resulted in higher earnings among workers in this sector, which translated into significant improvements in patient health and safety (Ruffini 2020).

Reducing costs associated with employee turnover

Higher wages and lower turnover are also beneficial to employers and third-party payers (Weller et al. 2020). Employers and institutions heavily bear the costs of turnover through spending on recruitment and training for new employees (Boushey and Glynn 2012). The cost savings from reduced turnover alone is estimated to be up to 40% of a position’s annual wage (Bahn and Cumming 2020).

A stable workforce and employees who want and are able to stay in their jobs creates stability for employers as well, which has powerful reputational and income effects (Washington State Department of Commerce 2019). Child care centers, for instance, operate on extremely thin margins and have high overhead costs, such as rent, safety regulations, mandated child-caregiver ratios, food, etc. (Workman and Jessen-Howard 2020; Oncken 2016). Saving on turnover would help centers meet these costs more easily, and higher pay might attract more applicants to open positions. It is important to note, though, that the cost savings from lower turnover—while helpful—is not sufficient to solve our child care challenges. Federal funding and public investment remain essential counterparts to helping employers meet costs and pay equitable wages.

Macroeconomic benefits

And finally, higher wages for care workers would have numerous macroeconomic benefits. A recent study of the nursing long-term-care industry found that raised wages prevented thousands of deaths, lowered the number of inspection violations, and reduced the cost of preventable care (Ruffini 2020). Estimations and simulations of large investments in care infrastructure have been shown to create millions of jobs (Palladino 2021). In addition, a better-paid care workforce can provide macroeconomic stimulus as workers spend more money on goods and services in the economy (Palladino and Lala 2021).

Estimates of the macroeconomic impact from investing in early child care and education vary, but they have overwhelmingly been shown to have a positive return. Heckman and others analyzed the Perry Preschool Program and found annual social rates of return between 7% and 10% (Heckman et al. 2010). A recent analysis of California ECE programs found that each dollar invested generated as much as $1.88 in increased economic activity, along with a range of other macroeconomic benefits such as increased labor force participation of women, increased parental earnings, and increased worker productivity (Powell, Thom et al. 2019). Karoly (2016) analyzed access to preschool and estimated a multiplier effect of $3–4. Abbott (2021) found that investing one dollar in high-quality pre-K would generate an additional $8.60 in economic benefits (Abbott 2021). A large part of these economic benefits takes the form of increased earnings for children later in life (CEA 2014). And finally, a recent study that followed up with participants of ECE programs later in life found that the benefits for both the original participants and their children were substantial (García et al. 2021).

In a prime example of the success of paying more, when hazard pay was raised (with benefits) during the pandemic, it was found to reduce economic hardship and improve retention (SEIU 775 and CAP 2021). These benefits should be extended, so that care work can have the protection and dignity needed to be desirable careers. The public role in both funding and in ensuring and enforcing these wage standards is key in making sure that funding is actually channeled into higher wages (Tung and Connolly 2015).

Conclusion

The pandemic recession shone a bright light on just how broken our care economy was and how much care workers were struggling. Our economic system, left to its own devices, has failed to recognize the worth of care work and maintain a well-functioning market (Jones 2020).

Care work is valuable (Coffey et al. 2020), demanding (Leberstein, Tung, and Connolly 2015), and requires specialized skills, given that workers are routinely making highly consequential decisions about and with people with disabilities, older adults, and children (NDWA 2019). Securing living wages, dignity of work, and safe working conditions for care workers is necessary for our collective survival. Better pay and work standards unambiguously improve the lives of workers themselves, but also strengthen the provision of care, secure a stable workforce, and reduce turnover (Weller et al. 2020; Ruffini 2020). These systemic improvements are essential given that demographic shifts will increase the need for care work in coming years.

Such an investment is also exactly what is needed as the economy recovers from the pandemic recession. When wages and conditions are better for care workers, care workers and their families are better off, employers and institutions are better off, and parents and others looking for caregiving for their families are better off. The macroeconomy benefits in turn as spending and productivity are boosted (Antonopoulos et al. 2010; Palladino and Lala 2021).

But improving conditions for care workers and ensuring access to quality care is not just about “return on investment” and protecting our interests; it is also a moral imperative to rectify long-standing systemic injustices. To address the wage suppression of care workers, we must first recognize that this suppression lies at the intersection of gender, racial justice, disability, and immigrant rights concerns (Chang 2017). The provision of care and the needs of people with disabilities, older adults, and children are not simply externalities to having a well-functioning and rewarded care economy. Rather, the intersectional concerns of those who are giving and receiving care should be at the very center of our discussions and policy choices.

By making deliberate policy choices to rectify historical and current harms—and grounding those policies in the experiences of the most marginalized of these workers (NDWA 2020), we ensure a shared prosperity for all (Bozarth, Western, and Jones 2020).

Notes

1. “Reproductive labor” refers to the labor that is necessary to sustain and nurture humans, both day to day and across generations. Per Glenn (1992), “Reproductive labor includes activities such as purchasing household goods, preparing and serving food, laundering and repairing clothing, maintaining furnishings and appliances, socializing children, providing care and emotional support for adults, and maintaining kin and community ties.”

2. United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Oman, Kuwait, and Bahrain.

3. Because of changes to industry and occupation categories in 2020, we combined newly disaggregated codes in the latter year with their aggregated counterparts in the former years. Although these codes differed, the following list is for the more detailed codes found in the 2020 data: Home health care workers are identified in the CPS by the occupations Nursing, psychiatric, and home health aides; Personal and home care aides; Home health aides; Personal care aides; Nursing assistants; Orderlies; and Psychiatric aides; and by the industries Private households, Home health care services, and Individual and family services. Child care workers are defined by the Child care worker occupation.

4. While the prior demographic analysis and results rely on the sample from the monthly CPS, wage analysis requires use of the Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group (CPS-ORG), again pooled from 2018 to 2020 and defined here as the “current” wage in 2020 dollars.

5. In San Francisco, California, it would take a full-time, full-year wage of about $54 dollars per hour for this family to make ends meet. We need a minimum federal standard to set a floor for care worker pay, but state and local governments should be allowed—and encouraged—to legislate higher minimums. EPI’s most recent family budget calculator figures have been updated to 2020 dollars for meaningful comparison.

6. Another reason for the public sector to step up is so that care is not only affordable but there is also less incentive for exploitative or illegal markets to meet the demand for care work (Reilly and Luscombe 2019).

7. England, Budig, and Folbre use a fixed-effects model based on job-switchers. It is possible that their reliance on job-switchers for identification may not provide reliable estimates for long-time workers within the care field. Use of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) up to data year 1993 also means that their sample does not allow measurement of the penalty among older workers nor does it fully account for the demographic characteristics of workers in caring fields in the economy today.

8. The authors use a fixed-effects model on the most recent data with later years of the NLSY. They identify the care penalty from occupational switchers and find a care premium in occupations such as doctors and other high-education/high-licensing fields. They also find that low pay of care workers cannot be explained by human capital differences and that care workers do not enjoy increasing pay with more experience as workers in other sectors do.

9. Others studies include Folbre and Smith 2017, which examines the pay penalties in the care sector for high-contact workers versus managers; Howes, Leana, and Smith 2012, which compares credentialed nurses with often-less-trained home health care workers; and Findlay, Findlay, and Stewart 2009, which focuses on the evaluation of caring skills themselves and gender differences in pay in the industry. Findlay, Findlay, and Stewart find that the skills are underestimated, notably because the gendered construction of caring skills contaminates their proper evaluation. Using longitudinal pairs combining CPS-ORG and O*NET data, Hirsch and Manzella (2015) find a larger care penalty for men than women. Similar to the other fixed-effects models, their identification strategy relies on job switchers and looks at the extent of caring across many caring professions, but their inclusion of skills and requirements imputed from the O*NET attempts to provide more similar comparables.

10. Specifically, we construct a log wage regression using a fully interacted model with gender and race/ethnicity and citizenship status controls. In additional to the demographic coefficients of interest, we control for age, age squared, educational attainment, and geographic division. These variables typically measure human capital returns to experience (loosely represented by age and age squared), skills (roughly characterized by formal educational attainment in five categories), and differences in the cost of living (measured using nine geographic divisions across the country).

11. The statistically significant coefficients on each gender-race/ethnicity-citizenship status interaction term are then applied proportionately to the shares of each demographic group found in the relevant care occupation. For example, the coefficient on the demographic interaction for Black women born in the U.S. yields a pay penalty of 34.3% compared with white U.S.-born men in the labor market at large. This pay penalty is weighted by 0.187 and 0.117, respectively, representing the shares of home health care workers and child care workers who are Black U.S.-born women. The weighted sum using the shares of each demographic group in each caring profession creates a total demographic pay penalty.

12. We estimate weekly as opposed to hourly wages here because of the difficulty of measuring teacher work hours within a week as well as over the year (Allegretto and Mishel 2020).

13. For child care workers with a college or advanced degree, we apply elementary and middle school wages according to their shares in the child care profession. For child care workers with educational attainment lower than a college degree, we apply the overall weekly earnings ratio of that level of educational attainment to the one required.

14. The final step involves applying the actual ratio of weekly to hourly earnings of child care workers to the imputed weekly value to back out a better standard for hourly child care wages.

References

Abbott, Sam. 2021. The Child Care Economy. Washington Center for Equitable Growth, September 15, 2021.

Addati, Laura, Umberto Cattaneo, Valeria Esquivel, and Isabel Valarino. 2018. Care Work and Care Jobs for the Future of Decent Work. Geneva: International Labour Organization, June 2018.

Allegretto, Sylvia, and Lawrence Mishel. 2020. Teacher Pay Penalty Dips but Persists in 2020: Public School Teachers Earn About 20% Less in Weekly Wages Than Nonteacher College Graduates. Economic Policy Institute, September 2020.

Altiraifi, Azza. 2019. Advancing Economic Security for People with Disabilities. Center for American Progress, July 2019.

Antonopoulos, Rania, Kijong Kim, Thomas Masterson, and Ajit Zacharias. 2010. “Investing in Care: A Strategy for Effective and Equitable Job Creation.” Working Paper no. 610, Levy Economics Institute of Bard College.

Bahn, Kate, and Carmen Sanchez Cumming. 2020. Improving U.S. Labor Standards and the Quality of Jobs to Reduce the Costs of Employee Turnover to U.S. Companies. Washington Center for Equitable Growth, December 2020.

Batt, Rosemary, Jae Eun Lee, and Tashlin Lakhani. 2014. A National Study of Human Resource Practices, Turnover, and Customer Service in the Restaurant Industry. Cornell Industrial and Labor Relations (ILR) School, January 2014.

Boldin-Woods, Davina. 2021. “We Do More Than Teach, We Build.” Words on the Workforce (Center for the Study of Child Care Employment blog), University of California, Berkeley, May 5, 2021.

Boushey, Heather, and Sarah Jane Glynn. 2012. There Are Significant Business Costs to Replacing Employees. Center for American Progress, November 2012.

Bozarth, Kendra, Grace Western, and Janelle Jones. 2020. Black Women Best: The Framework We Need for an Equitable Economy. Roosevelt Institute, September 2020.

Budig, Michelle J., Melissa J. Hodges, and Paula England. 2019. “Wages of Nurturant and Reproductive Care Workers: Individual and Job Characteristics, Occupational Closure, and Wage-Equalizing Institutions.” Social Problems 66, no. 2: 294–319. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spy007.

Campbell, Stephen, Angelina Del Rio Drake, Robert Espinoza, and Kezia Scales. 2021. Caring for the Future: The Power and Potential of America’s Direct Care Workforce. PHI National, January 2021.

Caven, Meg, Noman Khanani, Xinxin Zhang, and Caroline E. Parker. 2021. Center- and Program-Level Factors Associated with Turnover in the Early Childhood Education Workforce (REL 2021–069). U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Northeast & Islands, March 2021.

Center for the Study of Child Care Employment (CSCCE). 2021. The American Rescue Plan: Recommendations for Addressing Early Educator Compensation and Supports. University of California, Berkeley, May 2021.

Chang, Grace. 2017. “Inevitable Intersections: Care, Work, and Citizenship.” In Disabling Domesticity, edited by Michael Rembis, 163–194. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-48769-8_7.

Chappell, Bill. 2020. “Mississippi’s Ex-Welfare Director, 5 Others Arrested over ‘Massive’ Fraud.” NPR, February 6, 2020.

Coffey, Clare, Patricia Espinoza Revollo, Rowan Harvey, Max Lawson, Anam Parvez Butt, Kim Piaget, Diana Sarosi, and Julie Thekkudan. 2020. Time to Care: Unpaid and Underpaid Care Work and the Global Inequality Crisis. Oxfam, January 2020. https://doi.org/10.21201/2020.5419.

Connelly, Rachel, and Ebru Kongar. 2017. “Gender and Time Use in a Global Context.” In The Economics of Employment and Unpaid Labor. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-56837-3.

Connolly, Caitlin. 2015. “Wage and Hour Protections for Home Care Workers Take Effect” (blog post). National Employment Law Project, October 14, 2015.

Cooper, David. 2016. Balancing Paychecks and Public Assistance: How Higher Wages Would Strengthen What Government Can Do. Economic Policy Institute, February 2016.

Cooper, David, Zane Mokhiber, and Ben Zipperer. 2021. Raising the Federal Minimum Wage to $15 by 2025 Would Lift the Pay of 32 Million Workers: A Demographic Breakdown of Affected Workers and the Impact on Poverty, Wages, and Inequality. Economic Policy Institute, March 2021.

Costa, Daniel. 2019a. “Au Pair Lawsuit Reveals Collusion and Large-Scale Wage Theft from Migrant Women Through State Department’s J-1 Visa Program.” Working Economics Blog (Economic Policy Institute), January 15, 2019.

Costa, Daniel. 2019b. Employers Increase Their Profits and Put Downward Pressure on Wages and Labor Standards by Exploiting Migrant Workers. Economic Policy Institute, August 2019.

Costa, Daniel. 2021. Temporary Work Visa Programs and the Need for Reform: A Briefing on Program Frameworks, Policy Issues and Fixes, and the Impact of COVID-19. Economic Policy Institute, February 2021.

Costa, Daniel, and Phillip Martin. 2018. Temporary Labor Migration Programs: Governance, Migrant Worker Rights, and Recommendations for the U.N. Global Compact for Migration. Economic Policy Institute, August 2018.

Council of Economic Advisors (CEA). 2014. The Economics of Early Childhood Investments. Obama White House Archives, December 2014.

Derenoncourt, Ellora, and Claire Montialoux. 2021. “Minimum Wages and Racial Inequality.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 136, no. 1: 169–228, February 2021. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjaa031.

Dubois, Hans. 2021. “Wages in Long-Term Care and Other Social Services 21% Below Average.” Eurofound, March 25, 2021.

Economic Policy Institute (EPI). 2018. Family Budget Calculator (interactive data tool). Last updated March 2018.

Economic Policy Institute (EPI). 2020. “Cost of Child Care in the United States” (interactive data tool). Last updated October 2020.

Economic Policy Institute (EPI). 2021a. Current Population Survey Extracts, Version 1.0.20, https://microdata.epi.org.

Economic Policy Institute (EPI). 2021b. Unions Help Reduce Disparities and Strengthen Our Democracy (fact sheet). April 2021.

Edwards, Kathryn A. 2020. “‘Holes Just Big Enough’: Unemployment’s History with Black Workers.” RAND Blog, October 5, 2020.

England, Paula, Michelle Budig, and Nancy Folbre. 2002. “Wages of Virtue: The Relative Pay of Care Work.” Social Problems 49, no. 4: 455–473. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2002.49.4.455.

Findlay, Patricia, Jeanette Findlay, and Robert Stewart. 2009. “The Consequences of Caring: Skills, Regulation and Reward Among Early Years Workers.” Work, Employment, and Society 23, no. 3: 422–441. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017009337057.

Flood, Sarah, Miriam King, Renae Rodgers, Steven Ruggles, J. Robert Warren, and Michael Westberry. 2021. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, Current Population Survey: Version 9.0 [data set]. Minneapolis, Minn.: IPUMS, 2021. https://doi.org/10.18128/D030.V9.0.

Folbre, Nancy, and Kristin Smith. 2017. The Wages of Care: Bargaining Power, Earnings and Inequality. Washington Center for Equitable Growth, February 2017.

García, Jorge L., Frederik H. Bennhoff, Duncan E. Leaf, and James J. Heckman. 2021. “The Dynastic Benefits of Early Childhood Education.” Becker Friedman Institute Working Paper no. 2021-77, June 2021.

Glenn, Evelyn Nakano. 1985. “Racial Ethnic Women’s Labor: The Intersection of Race, Gender and Class Oppression.” Review of Radical Political Economics 17, no. 3: 86–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/048661348501700306.

Glenn, Evelyn Nakano. 1992. “From Servitude to Service Work: Historical Continuities in the Racial Division of Paid Reproductive Labor.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 18, no. 1: 1–43.

Glenn, Evelyn Nakano. 2012. Forced to Care: Coercion and Caregiving in America. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Press, 2012.

Global Ageing Network and the LeadingAge LTSS Center @UMass Boston (LTSS Center). 2018. Filling the Care Gap: Integrating Foreign-Born Nurses and Personal Care Assistants into the Field of Long-Term Services and Supports.

Gould, Elise. 2015. Child Care Workers Aren’t Paid Enough to Make Ends Meet. Economic Policy Institute, November 2015.

Gould, Elise. 2020. “Union Workers Are More Likely to Have Paid Sick Days and Health Insurance: COVID-19 Sheds Light on Least-Empowered Workers.” Working Economics Blog (Economic Policy Institute), March 12, 2020.

Gould, Elise, and Hunter Blair. 2020. Who’s Paying Now? The Explicit and Implicit Costs of the Current Early Care and Education System. Economic Policy Institute, January 2020.

Gould, Elise, Zane Mokhiber, and Kathleen Bryant. 2018. The Economy Policy Institute’s Family Budget Calculator: Technical Documentation. Economic Policy Institute, March 2018.

Gupta, Sarita. 2021. “Too Many Essential Care Workers Can’t Afford the Very Services They Provide.” Washington Post, May 26, 2021.