Briefing Paper #243

Executive summary

Economic recessions are often portrayed as short-term events. However, as a substantial body of economic literature shows, the consequences of high unemployment, falling incomes, and reduced economic activity can have lasting consequences. For example, job loss and falling incomes can force families to delay or forgo a college education for their children. Frozen credit markets and depressed consumer spending can stop the creation of otherwise vibrant small businesses. Larger companies may delay or reduce spending on R&D.

In each of these cases, an economic recession can lead to “scarring”—that is, long-lasting damage to individuals’ economic situations and the economy more broadly. This report examines some of the evidence demonstrating the long-run consequences of recessions. Findings include:

- Educational achievement: Unemployment and income losses can reduce educational achievement by threatening early childhood nutrition; reducing families’ abilities to provide a supportive learning environment (including adequate health care, summer activities, and stable housing); and by forcing a delay or abandonment of college plans.

- Opportunity: Recession-induced job and income losses can have lasting consequences on individuals and families. The increase in poverty that will occur as a result of the recession, for example, will have lasting consequences for kids, and will impose long-lasting costs on the economy.

- Private investment: Total non-residential investment is down by 20% from peak levels through the second quarter of 2009. The reduction in investment will lead to reduced production capacity for years to come. Furthermore, since technology is often embedded in new capital equipment, the investment slowdown can also be expected to reduce the adoption of new innovations.

- Entrepreneurial activity and business formation: New and small businesses are often at the forefront of technological advancement. With the credit crunch and the reduction in consumer demand, small businesses are seeing a double squeeze. For example, in 2008, 43,500 businesses filed for bankruptcy, up from 28,300 businesses in 2007 and more than double the 19,700 filings in 2006. Only 21 active firms had an initial public offering in 2008, down from an average of 163 in the four years prior.

There is also substantial evidence that economic outcomes are passed across generations. As such, economic hardships for parents will mean more economic hurdles for their children. While it is often said that deficits can cause transfers of wealth from future generations of taxpayers to the present, this cost must also be compared with the economic consequences of recessions that are also passed to future generations.

This analysis also suggests that efforts to stimulate the economy can be very effective over both the short- and long-run. Using a simple illustrative accounting framework, it is shown that an economic stimulus can lead to a short-run boost in output that outweighs the additional interest costs of the associated debt increase. This is especially true over a short horizon.

A recession, therefore, should not be thought of as a one-time event that stresses individuals and families for a couple of years. Rather, economic downturns will impact the future prospects of all family members, including children, and will have consequences for years to come.

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) passed earlier this year included tax cuts, transfers to state governments, and direct spending. The Obama administration has projected that the package would create or save

3.5 million jobs across the economy by the end of 2010 (Council of Economic Advisors 2009), with a 10-year budgetary cost of $787 billion. The impact of the package will likely reach well beyond short-term job creation. The increased spending will stimulate the broader economy, leading to greater economic output, greater national income, and a consequent boost in federal revenue (which would offset some of the initial cost). This boost to overall economic activity will also have long-term benefits to the economy by averting many of the costs that come along with recessions. And because the package also includes public investments in areas such as transportation infrastructure, energy efficiency, and education, it will yield economic dividends in years to come.

Too often the costs and benefits of fiscal stimulus are compared on unequal footing. The initial price tag of the recovery package, for example, is frequently portrayed as a one-time cost in revenue that would yield a one-time boost to the economy. However, the reality is that both the costs and benefits have ripple effects that should be considered over the long term. For example, economically stressed families find it more difficult to start new businesses, send their kids to college, or train for a new career. New entrants into the labor market are more likely to be un- or under-employed, which can have a lasting impact on their career paths and future income. An immediate boost to the economy in the near term can thus have lasting effects. Since the recovery package is funded through deficit spending (as it should be in order to maximize its impact), the true cost is spread out over a long period of time as well.

Further, it is often said that deficits can cause transfers of wealth from future generations of taxpayers to the present. While true, this cost must also be compared with the economic consequences of recessions that are also passed to future generations.

This Briefing Paper examines the potential long-run implications of the recession on families, businesses, and the economy. Short-term economic conditions can and do have long-lasting effects, including on: education; individual and family opportunities; private investments and technology; and entrepreneurial activity.

This report then uses a simple accounting framework to better judge the impacts on the economy. Such an analysis clearly shows that a temporary increase in federal spending—especially during an economic downturn—leads to an increase in national income in the near term, while spreading out the costs over many years. An evaluation of the recovery package should thus include the short-term boost to gross domestic product (GDP) and jobs; the long-term benefits of avoiding the scarring of a more severe recession; and the long-term interest costs of adding to the national debt (rather than the short-term fiscal impact).

Long-run impacts: “Scarring”

The traditional analysis of fiscal stimulus typically looks at the short-run impact of fiscal policy on GDP and job creation in the near term. However, economists have long recognized that short-run economic conditions can have lasting impacts. For example, job loss and falling incomes can force families to delay or forgo a college education for their children. Frozen credit markets and depressed consumer spending can stop the creation of otherwise vibrant small businesses. Larger companies may delay or reduce spending on R&D.

In each of these cases, an economic recession can lead to “scarring”—that is, long-lasting damage to individuals’ economic situations and the economy more broadly. The following sections detail some of what is known about how recessions can lead to long-term damage.

Economic damage

Recessions result in higher unemployment, lower wages and incomes, and lost opportunities more generally. Education, private capital investments, and economic opportunity are all likely to suffer in the current downturn, and the effects will be long-lived. While economies often see rapid growth during recovery periods (as unused capacity is returned to work), the drag due to the long-term damage will still prevent the recovery from reaching its full potential.

Education

As noted by many researchers, education—or “human capital”—plays a critical role in driving economic growth. For example, Delong, Golden, and Katz (2002) state that “human capital has played the principal role in driving America’s edge in twentieth-century economic growth.” As such, factors that lead to fewer years of educational attainment for the nation’s youth will have substantial consequences for years to come.

Recessions can impact educational achievement in a number of ways. First, a substantial body of literature addresses the importance of early childhood education (see, e.g., Heckman (2006, 2007) and the papers cited therein). Because education at this level (either pre-k or even earlier) is primarily driven by parental options and funding, factors that reduce families’ resources will impact the level and quality of education available to their children. For example, Dahl and Lochner (2008) find a direct effect of family income on math and reading test scores.

Furthermore, there is evidence that early childhood nutrition impacts cognitive development. Studies in developing countries have shown that improved nutrition can lead to greater grade attainment, reading comprehension, cognitive abilities, and ultimately wages later in life (see, e.g., Ruel and Hoddinott (2008) and Hoddinott et al. (2008)). The Dahl and Lochner results also suggest that the income impact is larger for families with younger children.

In a recession—when many families face financial hardships and poverty is rising—childhood nutrition can suffer. In 2007, 13 million U.S. households, including 12.7 million children, experienced “food insecurity”—or difficulty providing enough food for all family members; 4.7 million families faced a more severe disruption in the normal diet for some members (Nord et al. 2008). These numbers will almost certainly increase through 2009 as unemployment rises and incomes fall.

Second, educational achievement is determined by a number of factors outside of the school environment. For example, health services—from pre-natal care to dental and optometric care—can eliminate barriers to educational achievement. After-school and summer educational activities also affect in-school achievement and learning. Forced housing dislocations—and in the extreme, homelessness—impact educational outcomes as well. All of these influences on educational success are clearly shaped by economic downturns. The number of people without health insurance in 2008 was 46.3 million, with over 7 million kids under the age of 18 uninsured (U.S. Census 2009). With poverty (over 14 million kids in 2008) and foreclosures (4.3% of mortgage loans in the foreclosure process1) also on the rise, we can expect even more children will struggle with their education.

Finally, families struggling to get by are often forced to delay or abandon plans for continuing education. A recent survey of young adults found that 20% aged 18-29 have left or delayed college (Greenberg and Keating 2009). A survey conducted in Colorado found that a quarter of parents with children in two-year colleges had planned on sending their kids to four-year institutions before the recession (CollegeInvest 2009).

This delay or reduction in college attendance is costly. Not only does college attendance yield higher earnings, lower unemployment, and other benefits to the individual, but it also conveys myriad social benefits as well, including better health outcomes, lower incarceration rates, greater volunteerism rates, etc. (see, e.g., Baum and Pa-yea (2005) or Acemoglu and Angrist (2000)).

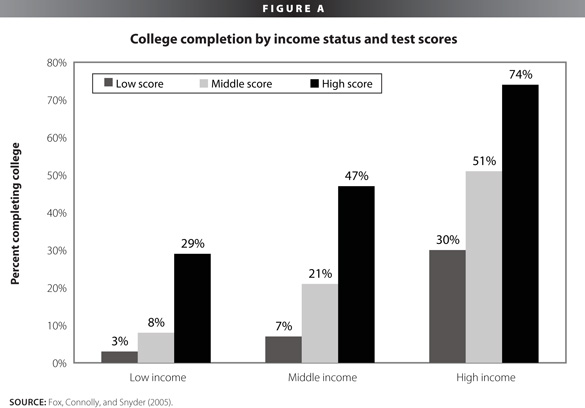

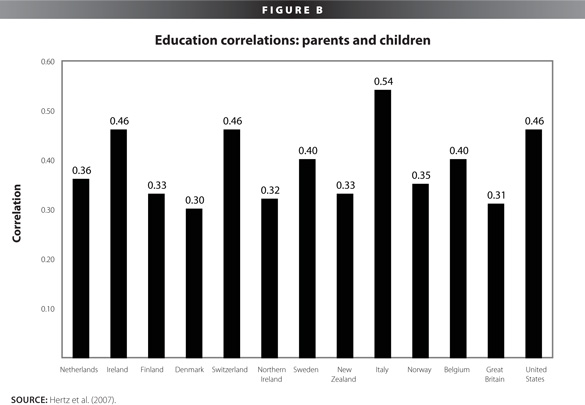

It is also important to note that the increased educational struggles for many kids and young adults will have lasting effects. Not only does increased educational success lead to higher wages and incomes for individuals and their families down the road (Card 1999), but it also leads to a greater likelihood of educational achievement for their offspring (Hertz et al. 2007; Fox et al. 2005). Figure A shows how higher-income parents are more likely to have children who complete college, and Figure B shows the high degree of correlation between parents and children in educational attainment both in the United States and abroad. As such, the economic downturn will have an impact lasting not just for years, but for generations.

Opportunity

There can be no doubt that recessions and high levels of unemployment lead to reduced economic opportunity for individuals and families. Job loss, reductions in incomes, and increases in poverty all result in losses to individuals and the broader economy.

To take just one example of lost opportunity, recent research has found that college graduates entering into the workforce during a recession will earn less than those entering in non-recessionary environments. Surprisingly, the findings also suggest that the income loss is not temporary: lifetime earnings and occupational paths are affected as well. According to Kahn (2009) “taken as a whole, the results suggest that the labor market consequences of graduating from college in a bad economy are large, negative, and persistent.” She finds an initial wage loss of 6% to 7% for each 1 percentage-point increase in the unemployment rate, and even after 15 years, the wage loss is still 2.5%.

Non-college graduates are likely to fare worse. While unemployment in the most recent recession has increased for all groups, those with less education and those with lower incomes face much higher rates than others.

Job loss

In the current recession, the unemployment rate has increased from 4.9% in December 2007 to 9.7% in August this year. There are currently about 15 million people who are unemployed—twice the number as at the start of the recession—with roughly 1 in 6 workers un- or underemployed. About 5 million workers have been unemployed for more than six months, and these long-term unemployed are the highest percentage of the total since 1948.

Loosing one’s job obviously creates problems for most individuals and families. The income loss can persist for years, even after a new job is taken (often at a lower salary).

Although the literature on the impact of job loss is too extensive to detail here, it is worth noting the evidence presented by Farber (2005). Using results from the Displaced Workers Survey through 2003, Farber finds that a job separation is costly:2 “In the most recent period (2001-03), about 35% of job losers are not employed at the subsequent survey date; about 13% re-employed full-time job losers are holding part-time jobs; full-time job losers who find new full-time jobs earn about 13% less on average on their new jobs than on the lost job…”

The impact of job loss goes well beyond income and earnings, and can impact one’s mental health (see Murphy and Athanasou (1999) for a review of 16 prior studies). It is also important to note that how one fares in a recession depends on a variety of factors. For example, older workers tend to be over-represented among the long-term unemployed when compared with other age groups.

Poverty and wealth

Simply put, poverty is not good for the economy. When children grow up in poverty, they are more likely, later in life, to have low earnings, commit crimes, and have poor health. Holtzer et al. (2007) estimate the cumulative costs to the economy of childhood poverty to be about $500 billion per year, or about 4% of GDP. There is significant evidence that poverty has lasting consequences for kids, including educational achievement, cognitive development, and emotional and behavioral outcomes.3 As noted above, family income can be expected to impact educational attainment in various ways, but falling incomes and higher poverty levels also impact adults’ opportunities as well.

Wealth also shapes economic opportunities, providing a lifeline when times are tough (such as a recession) and can finance additional education, retraining, or the startup costs of a new business. Unfortunately, a large share of the country has little in the way of wealth: in 2004 approximately 30% of households had a net worth of less than $12,000 (Mishel et al. 2009). This problem is even more severe for certain populations: the median financial wealth for blacks—which includes liquid and semi-liquid assets such as mutual funds, trusts, and bank account holdings—was just $300 in 2004.

Economic mobility

As noted above, inter-generational mobility—or the lack thereof—can lead to persistent impacts of recessions.

Poorer families can lead to less opportunity and worse economic outcomes for their children through a variety of mechanisms—be it through nutrition, educational attainment, or access to wealth. A recession, therefore, should not be thought as a one-time event that stresses individuals and families for a couple of years. Rather, economic downturns will impact the future prospects of all family members, including children, and will have consequences for years to come.

A range of findings suggest that economic outcomes— especially one’s position in the income and wealth distribution—are often carried over from one to the next (Solon 1992; Hertz 2006). More directly related to job loss, Oreopoulos et al. (2005) looks at labor market earnings of children whose fathers experienced a job loss. Not only did the job loss lead to a persistent loss in family income, but the next generation also had earnings 9% lower than similar children whose father did not experience unemployment.

Private investment

Perhaps the most obvious areas in which recessions can slow economic growth is in those of investments and R&D. Economists have long recognized the central role of investment and technology as key contributors to economic growth.4

Recessions can and do lead to decreases in investment spending and the adoption of new technologies. This is a result of at least four factors. First, an economic downturn will lead to a drop in demand for firms’ products as customers’ incomes decline, thus lowering the return to investments. Second, limited access to credit will limit firms’ ability to invest. Third, recessions are periods of increased uncertainty that may lead firms to retrench toward “core” products and production techniques, and therefore they may be less likely to experiment with new products and techniques. Finally, we must also consider the interaction between human and physical capital. Technology is often embedded in new physical equipment: as production and employment is reduced, there is less purchasing of newer equipment. As a result, workers are less able to utilize their skills, and there is less need to “up-skill” current employees or hire additional employees with new skills.5

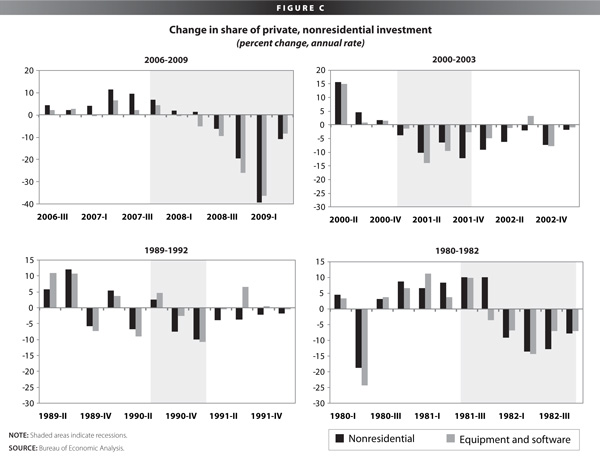

Figure C shows the growth of non-residential investment in each of the last four recessions, as well as a more narrow category of equipment and software (thus excluding structures). Over the 1947-2009 period, annualized quarterly non-residential investment has averaged 4.7%, while investment in equipment and software have averaged 5.9%. As the figure shows, investment contracts significantly during recessions. It also shows the severity of the current downturn, with total non-residential investment down by 20% from peak levels through the second quarter of 2009.

To illustrate with a concrete example the impact in one particular area, consider the deployment of broadband access. There is evidence that universal access to broadband internet connectivity could yield significant economic benefits (see Crandall and Jackson (2001) or Atkinson et al. (2009)). Yet investments in information processing equipment/software and computers/peripheral equipment are down from peak levels by 11% and 15%, respectively.

The consequences of the lower levels of investment are obvious. Less capital investment today means lower levels of economic production in the future. Lower levels of physical investment can also mean lower levels of productivity and hence wages.6 The impact will last well beyond the official end of the current recession.

Entrepreneurial activity: Business formation and expansion

Aside from the general downturn in investment activity, recessions—and particularly ones that involve a credit crunch as the current one does—can hamper small business formation and entrepreneurial activity.

From a long-run perspective, new business formation is important because of the links between innovation, R&D, and new start-ups. New businesses are often formed to develop, implement, and market new technologies. To take one example, Kirchhoff et al. (2002) examines the link between university-based R&D activity and new business creation and finds that “university R&D expenditures are significantly related to new firm formations in the same [Local Market Area].” Thus delays in new business formation may mean delays in the development and adoption of new technologies, causing long-run damage to the economy.7

There are several ways recessions can slow business formation and expansion. First, to state the obvious, new businesses need new customers. An economic slowdown means that there is less spending overall; therefore, people looking to start a new business may decide to delay ventures until demand returns to normal levels. Second, new businesses need new investors and creditors. Lower incomes and wealth levels may mean that new business will find it more difficult to find individual investors, and credit constraints may limit borrowing from private banks.

According to a recent report by the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA 2009): “The credit freeze in the short-term funding market had a devastating effect on the economy and small firms. By late 2008, the normal production of goods and services had virtually stalled.” A survey of loan officers also suggests that standards for small-firm commercial and industrial loans were significantly tightened.

Not only do recessions make it more difficult to start a new business, they also can undermine new start-ups that are struggling to get by. There may be many new businesses (and business mod

els) that would be successful in ordinary times but are unable to succeed due to a lack of demand or credit. In 2008, 43,500 businesses filed for bankruptcy, up from 28,300 businesses in 2007 and more than double the 19,700 filings in 2006 (SBA 2009).

The recession’s impact can also be seen in initial public offering (IPO) activity. Firms use capital raised from IPOs to expand activities. In 2008, there were just 21 IPOs for operating companies, down from an annual average of 163 in the four years prior (Ritter 2009).8 Furthermore, the median age of IPOs in 2008 was slightly higher than in past years, meaning that it is the more-established firms that are receiving the capital influx.

It is tempting to conclude that recessions merely delay new business formation, and that over time delayed plans will eventually be implemented. However, for many new businesses, there is a limited opportunity to get going. Furthermore, innovative new firms often build on prior innovation and technology platforms. A delay in one business may mean many others will be delayed as well, creating a ripple effect across a broader range of businesses.

Time path of investment— short-run impacts and costs

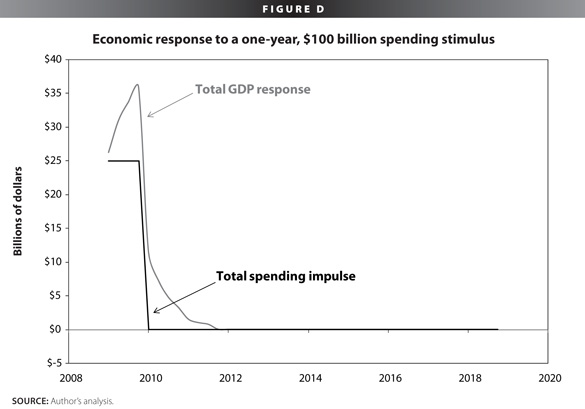

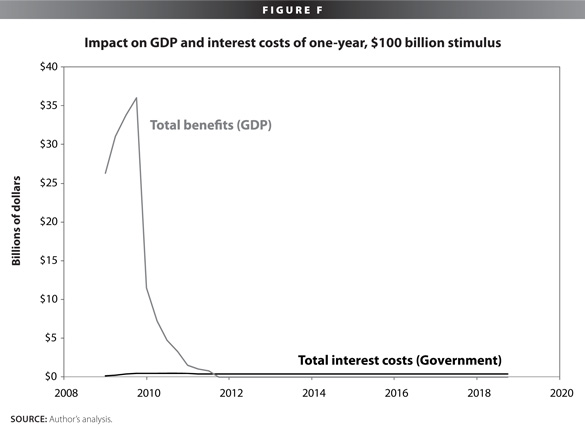

To better understand the impact of economic stimulus on the overall economy and on the federal government’s finances, consider a hypothetical one-year, $100 billion package of federal spending on public investments starting at the beginning of 2009. Figure D shows the impact of this spending, assuming it is spread evenly throughout the year ($25 billion per calendar quarter). Using estimates of the macroeconomic impact of a spending surge,9 the figure also shows how GDP responds to this increase in spending. The economic impact will be larger than the initial impulse—federal dollars will increase private incomes, raise public consumption, and stimulate even more production, resulting in what’s known as the “multiplier effect.” The impact also lasts beyond the one-year window as the increased economic production ripples through the economy.

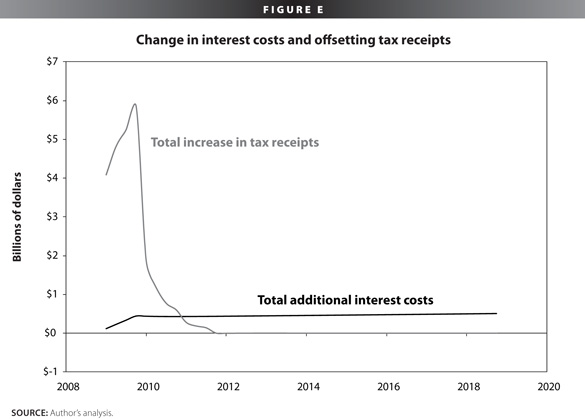

Beyond the short- and medium-run boost to GDP, the spending increase will have impacts on the federal budget. In particular, the boost to economic activity (relative to a no-stimulus scenario) will lead to a boost in federal revenues as individual and business incomes increase. However, if the spending is deficit financed— thus resulting in an increase to the national debt—the federal government would see additional interest costs over time. Figure E shows the relative magnitude of these two impacts (assuming a constant interest rate).10 While the revenue impact is temporary, the higher interest costs, however, will continue.11

Over the next 10 years, federal revenue would increase by a cumulative $25 billion over baseline, offsetting a portion of the cost of the stimulus. The extra interest expenses (after factoring in the revenue boost) would total $18 billion over the next decade. Looking over longer horizons would, of course, increase this net cost. On a present discounted basis projecting into the indefinite future, the net increase in interest payments would be about $92 billion—smaller than the “headline” $100 billion cost. Over time, as the economy grows, the additional interest payments will fall relative to the economy’s size: in this example, additional annual interest costs would fall to just 0.01% of GDP after 10 years.

The benefit to the overall economy over this time, however, would be approximately $154 billion in present value terms (see Figure F), which is significantly larger than the $18 billion boost in interest costs over the decade.

In short, the real economic cost to the federal government of the stimulus is less than the $100 billion in expenditures because the higher tax receipts from greater economic activity offset some of the cost. These costs can also be spread out over a number of years, and can be repaid at a time when the economy has higher output and is thus better able to afford the interest payments. At the same time, the immediate impact of the stimulus to the broader economy is substantially greater than both the overall cost as well as the additional interest payments that would be required to finance the spending boost.

A similar analysis of the impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act shows the benefits to GDP relative to the fiscal cost. The present value of the boost to GDP is over $1 trillion over the next decade, while the present value of the interest payments is $183 billion—nearly a 6-to-1 return on the investment over this horizon. Over the infinite horizon, the return is still a substantial 1.4-to-1.12

It is important to note that this analysis is based on fairly conventional economic models that are designed to analyze short-term dynamics. In particular, the model assumes that there will be little to no long-term impact of investments on economic output—either in terms of total activity or the growth over time. However, as noted above, there are many reasons to believe that a short-term recession can indeed have a lasting, near-permanent impact on economic production, and thus a temporary boost can have a very long-lived impact on GDP.

Conclusion

Recessions can and do have lasting impact. As such, we should consider the costs of fighting recessions as long-term investments.

In a globally competitive environment, the loss of investment, R&D, education, and skills more generally are even more important as they can undercut the United States’ global competitive advantages. In a global context, righting the ship as quickly and completely as possible is essential in limiting the long-term damage.

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act has and will add to the fiscal deficit, but those costs—in terms of added interest payments—should be viewed as necessary to provide a short-term boost that allows us to avoid even greater long-term damage to families and to the economy.

Appendix: Recovery and Reinvestment Act

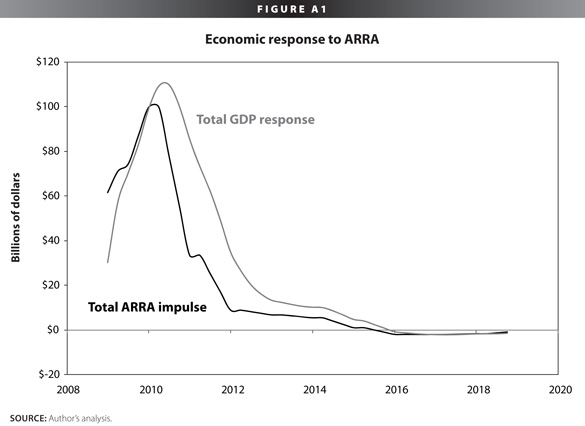

Figure A1 shows the stimulative impulse of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) as measured by the outlay estimates of the spending proposals and the revenue estimates of the tax proposals, as estimated by the Congressional Budget Office.13 The outlays and tax reductions are expected to begin quickly and then peak in 2010, with smaller impacts in the out-years. The figure also shows the impact of these policies on GDP assuming the same multiplier effect on the overall economy as described above.

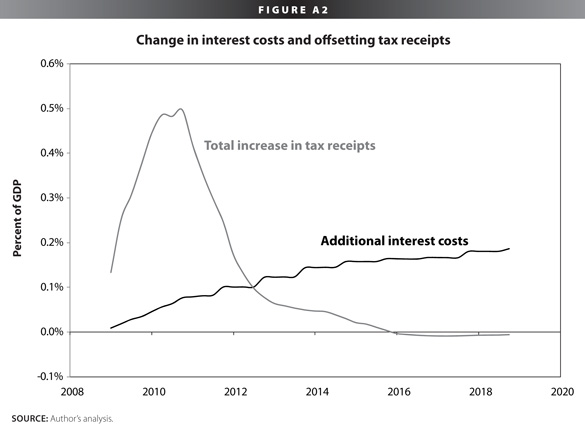

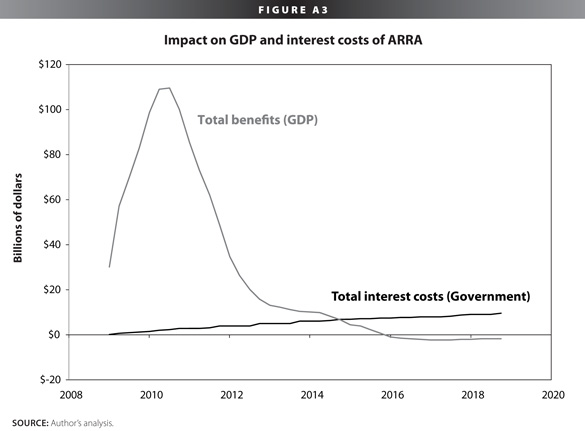

As with the example above, the stimulus leads to substantial increases in GDP, thus creating revenues that partially offset the overall cost of the package. The interest costs to the federal government increase over time due to the additional debt created, and also due to expected increases in the interest rate. However, the additional interest costs level off to about 0.14% of GDP by the middle of the next decade (see Figure A2).

Again, since the costs are spread into the future and the benefits

to the economy are immediate, the 10-year benefits substantially outweigh the interest costs (see Figure A3). The present value of the boost to GDP is over $1 trillion over the next decade, while the present value of the interest payments is $183 billion—nearly a 6-to-1 return on the investment. Over the infinite horizon, the return is still 1.4-to-1.

Endnotes

1. See Mortgage Bankers Association (2009).

2. Farber looks only at those separated “not ‘for cause.’”

3. For example, see research and data cited in The Connecticut Commission on Children (2004).

4. See, e.g., Solow (1957), Lucas (1988), Romer (1986).

5. See Autor, et al. (2002) for a discussion of some of these factors.

6. Higher productivity need not necessarily lead to higher wages on average (see Mishel et al. 2009); however, wage gains are more likely in an environment with rapid productivity gains.

7. For more discussion of the link between entrepreneurial activity, small businesses, and innovation, see Baumol (2005).

8. This sample “excludes ADRs, unit offers, closed-end funds, RE-ITs, partnerships, banks and S&Ls, and stocks not listed on CRSP (CRSP includes Amex, NYSE, and NASDAQ stocks).”

9. The multipliers are taken to be the same as in CEA (2009), at http://www.whitehouse.gov/assets/documents/Estimate_of_Job_ Creation.pdf. Note that the analysis here is not derived from simulating a macroeconomic model, and, as such, should be taken as broadly illustrative, ballpark estimates of the impact on GDP. Also, the analysis here is of a temporary surge in spending or tax reduction, while the estimates provided in the CEA analysis are for a permanent increase. We assume that the temporary increase is equivalent to a permanent increase followed by later permanent decreases. To the extent that expectations drive the final results in the macro models surveyed by the CEA report, our estimates will differ from the estimates derived from any individual model.

10. For illustrative purposes, federal interest payments are here assumed to remain at current levels as a percent of debt over the 10-year horizon. This assumption is relaxed in the analysis below to incorporate higher interest costs as interest rates are expected to increase from current levels, consistent with CBO estimates.

11. The interest costs mapped here assume the one-time spending increase permanently adds to the national debt, and include the impact of higher revenues.

12. This calculation assumes that the additional interest is paid off in each year.

13. The data used here are a quarterly smoothing of the annual data provided by the CBO. See Congressional Budget Office, Letter to Charles Grassley, March 2, 2009, at http://www. cbo.gov/ftpdocs/100xx/doc10008/03-02-Macro_Eff ects_of_ ARRA.pdf.

References

Acemoglu, Daron and Joshua Angrist. 2000. How large are human capital externalities? Evidence from compulsory schooling laws. NBER Macroeconomics Annual. Vol. 15, pp. 9-59.

Atkinson, Robert D., Daniel Castro and Stephen J. Ezell. 2009. “The Digital Road to Recovery: A Stimulus Plan to Create Jobs, Boost Productivity and Revitalize America.” Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, January 2009, at http://www.itif.org/files/roadtorecovery.pdf.

Autor, David H., Frank Levy, and Richard Murnane. 2002. Upstairs, downstairs: computers and skills on two floors of a large bank. Industrial and Labor Relations Review. Vol. 55, No. 3, pp. 432-47.

Baum, S., and K. Payea. 2005. Education pays: The benefits of higher education for individuals and society. Washington, D.C.: College Board at http://www.collegeboard.com/prod_ downloads/press/cost04/EducationPays2004.pdf.

Baumol, William. 2005. “Small Firms: Why Market-Driven Innovation Can’t Get Along Without Them. The Small Business Economy: A Report to the President.” Chapter 8. Washington D.C.: U.S. Small Business Administration, Office of Advocacy, at http://www.sba.gov/ADVO/research/sbe_05_ch08.pdf.

Card, D. 1999. “The Causal Effect of Education on Earnings.” In O. Ashenfelter and D. Card, eds., Handbook of Labor Economics, Vol 3. Elsevier-North Holland.

CollegeInvest. 2009. Survey: Economy Weighing on Colorado Parents When Planning for College. May 29, 2009, at http://www.collegeinvest.org/PDF/CIPollResults_5.29.09.pdf.

The Connecticut Commission on Children. 2004. “Children and the Long-Term Effects of Poverty” 2004, at http://www.cga.ct.gov/COC/PDFs/poverty/2004_poverty_report.pdf.

Council of Economic Advisors. 2009. “Estimates of Job Creation from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009” May, at http://www.whitehouse.gov/administration/eop/cea/Estimate-of-Job-Creation/.

Crandall, R. W., Charles Jackson. 2001. The $500 Billion Opportunity: The Potential Economic Benefit of Widespread Diffusion of Broadband Internet Access. Washington, D.C., Criterion Economics. http://www.att.com/public_affairs/broadband_policy/BrookingsStudy.pdf.

Dahl, G., and L. Lochner. 2008. “The Impact of Family Income on Child Achievement: Evidence from the Earned Income Tax Credit.” National Bureau of Economic Research, December. http://www.nber.org/papers/w14599

Delong, J.B., Claudia Golden, and L. Katz. 2002. “Sustaining U.S. Economic Growth.” July. http://j-bradford-delong.net/Econ_Articles/GKD_fi nal3.pdf

Farber, Henry S. 2005. “What Do We Know about Job Loss in the United States? Evidence from the Displaced Workers Survey, 1984-2004.” Working paper #498, Princeton University, 2005, at http://www.irs.princeton.edu/pubs/pdfs/498.pdf.

Fox, Mary Ann, B.A. Connolley, and T.D. Snyder. 2005. “Youth Indicators, 2005: Trends in the Well-Being of American Youth.” U.S. Department of Education, Washington, D.C. July.

Greenberg, Anna, and Jessica Keating. 2008. “Young Adults: Trying to Weather a Recession.” Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research, April, at http://qvisory.org/cms/0000/0141/Trying_ to_Weather_a_Recession_Study.pdf.

Heckman, J. J. 2006. Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science. Vol. 312, No. 5782.

Heckman, J. J. and D. V. Masterov. 2007. “The Productivity Argument for Investing in Young Children.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. W13016. Cambridge, Mass.: NBER.

Hertz, Tom. 2006. “Understanding Mobility in America.” Center for American Progress, April 26, 2006, at http://www.americanprogress.org/kf/hertz_mobility_analysis.pdf.

Hertz, Tom, Tamara Jayasundera, Patrizio Piraino, Sibel Selcuk, Nicole Smith and Alina Verashchagina. 2007. The inheritance of educational inequality: international comparisons and fifty year trends. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy. Vol. 7, No. 2 (Advances).

Hoddinott, J. A Maluccio, J. R. Behrman, R. Flores, and R. Martorell. 2008. Effect of a nutrition intervention during early childhood on economic productivity in Guatemalan adults. Lancet. Vol. 371, pp. 411–16.

Holzer, H., D. W. S., Greg J. Duncan, and Jens Ludwig. 2007. “The Economic Costs of Poverty: Subsequent Effects of Children Growing Up Poor.” Center for American Progress. http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/2007/01/pdf/poverty_ report.pdf.

Kahn, Lisa B. 2009. “The Long-Term Labor Market Consequences of Graduating from College in a Bad Economy.” Yale School of Management. (forthcoming Labour Economics), at http://mba.yale.edu/faculty/pdf/kahn_longtermlabor.pdf.

Kirchhoff, Bruce, and Catherine Armington (BJK Associates). 2002. The Influence of R&D Expenditures on New Firm Formation and Economic Growth. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Small Business Administration, Office of Advocacy.

Marie Ruel and John Hoddinott. 2008. “Investing in Early Childhood Nutrition.” IFPRI Policy Brief 8, November at http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/48929/2/bp008.pdf.

Mishel, Lawrence, Heidi Shierholz, and Jared Bernstein. 2009. The State of Working America 2008/2009. Washington, D.C.: Economic Policy Institute.

Mortgage Bankers Association. 2009. “Delinquencies Continue to Climb, Foreclosures Flat in Latest MBA National Delinquency Survey,” August 20, 2009, at http://www.mbaa.org/ NewsandMedia/PressCenter/70050.htm.

Murphy, Gregory C., and James A. Athanasou. 1999. The effect of unemployment on mental health. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. Vol. 72, pp. 83–99.

Nord, Mark, Margaret Andrews, and Steven Carlson. 2008. “Household Food Security in the United States, 2007.” Economic Research Report No. (ERR-66) USDA, November 2008, at http://www.ers.usda.gov/Publications/ERR66/.

Oreopoulos, P., Marianne Page, and Ann Huff Stevens. 2005. “The Intergenerational Effects of Worker Displacement.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 11587: Cambridge, Mass.:NBER.

Ritter, Jay R. 2009. “Some Factoids about the 2008 IPO Market.” University of Florida, at http://bear.cba.ufl.edu/ritter/IPOs2008Factoids.pdf.

Romer, P. 1986. Increasing returns and long-run growth. Journal of Political Economy. Vol. 94, No. 5, pp. 1002-37.

Ruel, Marie, and John Hoddinott. 2008. “Investing in Early Childhood Nutrition.” International Food Policy Research Institute, November. http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/48929/2/bp008.pdf

Solon, G. 1992. Intergenerational income mobility in the United States. American Economic Review. Vol. 82, No. 3, pp. 393-408.

Small Business Administration. 2009. “The Small Business Economy.” Washington, D.C.: SBA. http://www.sba.gov/ADVO/research/sb_econ2009.pdf

U.S. Census. 2009. “Income, Poverty and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States, 2008.” September 2009 at http://www.census.gov/prod/2009pubs/p60-236.pdf