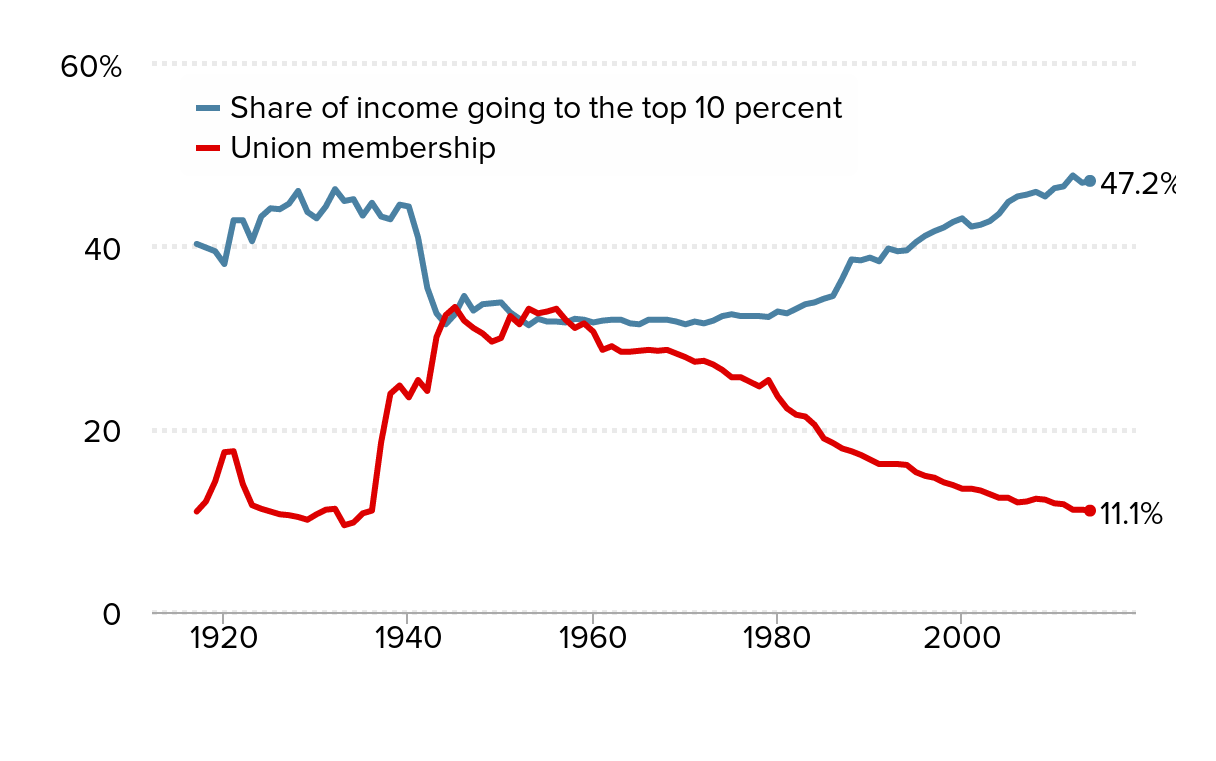

As union membership has fallen over the last few decades, the share of income going to the top 10 percent has steadily increased. Union membership fell to 11.1 percent in 2014, where it remained in 2015 (not shown in the figure). The share of income going to the top 10 percent, meanwhile, hit 47.2 percent in 2014—only slightly lower than 47.8 percent in 2012, the highest it has been since 1917 (the earliest year data are available). When union membership was at its peak (33.4 percent in 1945) the share of income going to the top 10 percent was only 32.6 percent.

As union membership has fallen, the top 10 percent have been getting a larger share of income: Union membership and share of income going to the top 10%, 1917–2014

| Year | Union membership | Share of income going to the top 10 percent |

|---|---|---|

| 1917 | 11.0% | 40.3% |

| 1918 | 12.1% | 39.9% |

| 1919 | 14.3% | 39.5% |

| 1920 | 17.5% | 38.1% |

| 1921 | 17.6% | 42.9% |

| 1922 | 14.0% | 42.9% |

| 1923 | 11.7% | 40.6% |

| 1924 | 11.3% | 43.3% |

| 1925 | 11.0% | 44.2% |

| 1926 | 10.7% | 44.1% |

| 1927 | 10.6% | 44.7% |

| 1928 | 10.4% | 46.1% |

| 1929 | 10.1% | 43.8% |

| 1930 | 10.7% | 43.1% |

| 1931 | 11.2% | 44.4% |

| 1932 | 11.3% | 46.3% |

| 1933 | 9.5% | 45.0% |

| 1934 | 9.8% | 45.2% |

| 1935 | 10.8% | 43.4% |

| 1936 | 11.1% | 44.8% |

| 1937 | 18.6% | 43.3% |

| 1938 | 23.9% | 43.0% |

| 1939 | 24.8% | 44.6% |

| 1940 | 23.5% | 44.4% |

| 1941 | 25.4% | 41.0% |

| 1942 | 24.2% | 35.5% |

| 1943 | 30.1% | 32.7% |

| 1944 | 32.5% | 31.5% |

| 1945 | 33.4% | 32.6% |

| 1946 | 31.9% | 34.6% |

| 1947 | 31.1% | 33.0% |

| 1948 | 30.5% | 33.7% |

| 1949 | 29.6% | 33.8% |

| 1950 | 30.0% | 33.9% |

| 1951 | 32.4% | 32.8% |

| 1952 | 31.5% | 32.1% |

| 1953 | 33.2% | 31.4% |

| 1954 | 32.7% | 32.1% |

| 1955 | 32.9% | 31.8% |

| 1956 | 33.2% | 31.8% |

| 1957 | 32.0% | 31.7% |

| 1958 | 31.1% | 32.1% |

| 1959 | 31.6% | 32.0% |

| 1960 | 30.7% | 31.7% |

| 1961 | 28.7% | 31.9% |

| 1962 | 29.1% | 32.0% |

| 1963 | 28.5% | 32.0% |

| 1964 | 28.5% | 31.6% |

| 1965 | 28.6% | 31.5% |

| 1966 | 28.7% | 32.0% |

| 1967 | 28.6% | 32.0% |

| 1968 | 28.7% | 32.0% |

| 1969 | 28.3% | 31.8% |

| 1970 | 27.9% | 31.5% |

| 1971 | 27.4% | 31.8% |

| 1972 | 27.5% | 31.6% |

| 1973 | 27.1% | 31.9% |

| 1974 | 26.5% | 32.4% |

| 1975 | 25.7% | 32.6% |

| 1976 | 25.7% | 32.4% |

| 1977 | 25.2% | 32.4% |

| 1978 | 24.7% | 32.4% |

| 1979 | 25.4% | 32.3% |

| 1980 | 23.6% | 32.9% |

| 1981 | 22.3% | 32.7% |

| 1982 | 21.6% | 33.2% |

| 1983 | 21.4% | 33.7% |

| 1984 | 20.5% | 33.9% |

| 1985 | 19.0% | 34.3% |

| 1986 | 18.5% | 34.6% |

| 1987 | 17.9% | 36.5% |

| 1988 | 17.6% | 38.6% |

| 1989 | 17.2% | 38.5% |

| 1990 | 16.7% | 38.8% |

| 1991 | 16.2% | 38.4% |

| 1992 | 16.2% | 39.8% |

| 1993 | 16.2% | 39.5% |

| 1994 | 16.1% | 39.6% |

| 1995 | 15.3% | 40.5% |

| 1996 | 14.9% | 41.2% |

| 1997 | 14.7% | 41.7% |

| 1998 | 14.2% | 42.1% |

| 1999 | 13.9% | 42.7% |

| 2000 | 13.5% | 43.1% |

| 2001 | 13.5% | 42.2% |

| 2002 | 13.3% | 42.4% |

| 2003 | 12.9% | 42.8% |

| 2004 | 12.5% | 43.6% |

| 2005 | 12.5% | 44.9% |

| 2006 | 12.0% | 45.5% |

| 2007 | 12.1% | 45.7% |

| 2008 | 12.4% | 46.0% |

| 2009 | 12.3% | 45.5% |

| 2010 | 11.9% | 46.4% |

| 2011 | 11.8% | 46.6% |

| 2012 | 11.2% | 47.8% |

| 2013 | 11.2% | 47.0% |

| 2014 | 11.1% | 47.2% |

Source: Piketty and Saez (2014), Gordon (2013), and Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Population Survey public data series

Data on union density follows the composite series found in Historical Statistics of the United States; updated to 2014 from unionstats.com. Income inequality (share of income to top 10%) from Piketty and Saez, “Income Inequality in the United States, 1913-1998, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(1), 2003, 1-39. Updated data for this series and other countries, is available at the Top Income Database. Updated 2016.

The single largest factor suppressing wage growth for working people and suppressing union membership over the last few decades has been the erosion of collective bargaining. This erosion has affected both union and nonunion workers alike, contributing to wage stagnation and growth in inequality. To boost wages for working people, policymakers need to intentionally tilt power back to working people by strengthening their rights to stand together and negotiate collectively for better wages and benefits, raising and improving labor standards, and achieving persistent low unemployment.