Workers of color made historic gains over the last five years, but Trump’s anti-worker and anti-equity agenda threatens to reverse this progress

Workers of color make up more than 40% of the U.S. labor force, and that share is growing as more of the white non-Hispanic population reaches retirement age and recent immigration trends help sustain the growth of our labor force and economy. Over the last five years, workers of color—who identify as Black, Hispanic, Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI), and American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN)—made significant gains in employment and earnings. This was a direct result of the Biden-Harris administration’s commitment to full employment during the post-pandemic recovery and the Federal Reserve’s successful navigation of a soft landing. But Trump’s anti-worker, anti-immigrant policy actions could soon erase this progress.

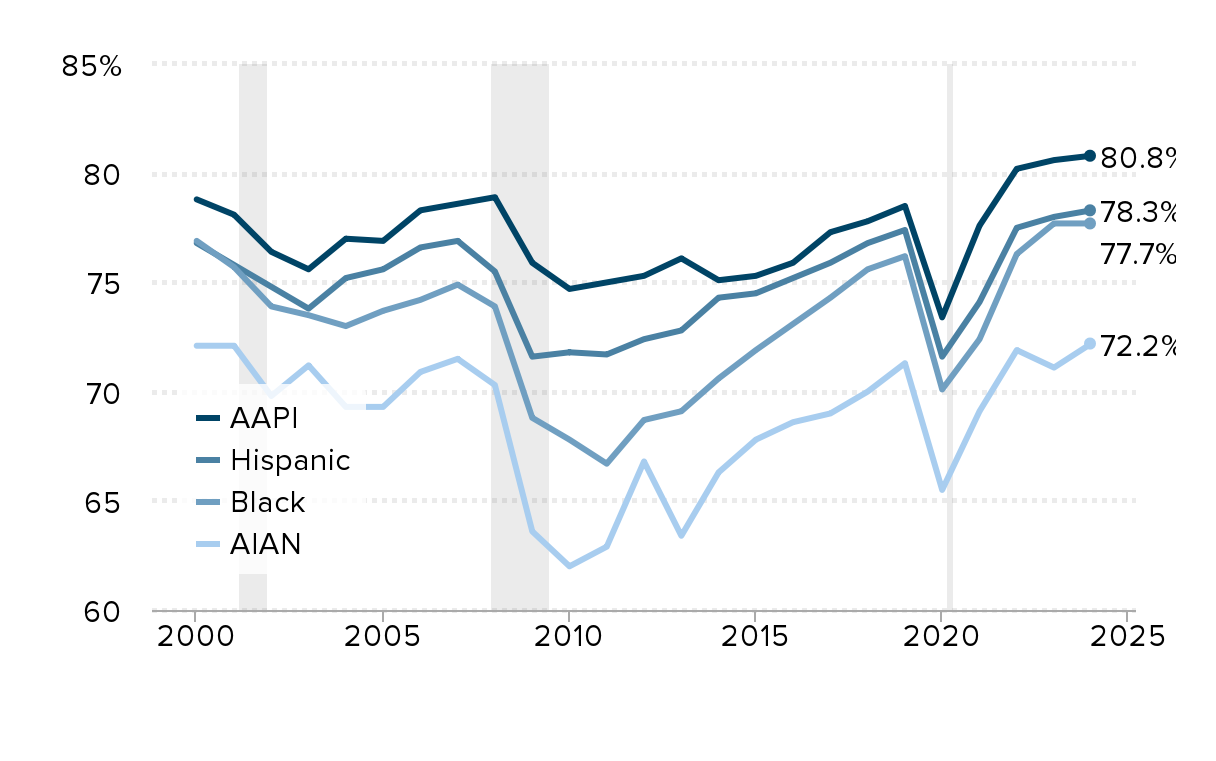

The broad-based nature of the labor market recovery is most evident when examining the employment-to-population (EPOP) ratio of prime-age workers between the ages of 25 and 54. Unlike the unemployment rate, the EPOP ratio is not influenced by changes in labor force participation since it captures the share of workers during a given period that have a job. The prime-age EPOP ratio is also less influenced by college attendance and the aging of the population when compared with the employment rate of all workers. As shown in Figure A, the employment rate of prime-age Black, Hispanic, AAPI, and AIAN workers hit record highs within the past few years. For example, the share of prime-age Black workers with a job reached a historic peak of 77.7% in 2023.

The employment rate of prime-age workers of color reached historic heights in the past few years: Prime-age employment-to-population ratios by race and ethnicity, 2000–2024

| year | Black | Hispanic | AIAN | AAPI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 76.9% | 76.8% | 72.1% | 78.8% |

| 2001 | 75.7% | 75.8% | 72.1% | 78.1% |

| 2002 | 73.9% | 74.8% | 69.8% | 76.4% |

| 2003 | 73.5% | 73.8% | 71.2% | 75.6% |

| 2004 | 73.0% | 75.2% | 69.3% | 77.0% |

| 2005 | 73.7% | 75.6% | 69.3% | 76.9% |

| 2006 | 74.2% | 76.6% | 70.9% | 78.3% |

| 2007 | 74.9% | 76.9% | 71.5% | 78.6% |

| 2008 | 73.9% | 75.5% | 70.3% | 78.9% |

| 2009 | 68.8% | 71.6% | 63.6% | 75.9% |

| 2010 | 67.8% | 71.8% | 62.0% | 74.7% |

| 2011 | 66.7% | 71.7% | 62.9% | 75.0% |

| 2012 | 68.7% | 72.4% | 66.8% | 75.3% |

| 2013 | 69.1% | 72.8% | 63.4% | 76.1% |

| 2014 | 70.6% | 74.3% | 66.3% | 75.1% |

| 2015 | 71.9% | 74.5% | 67.8% | 75.3% |

| 2016 | 73.1% | 75.2% | 68.6% | 75.9% |

| 2017 | 74.3% | 75.9% | 69.0% | 77.3% |

| 2018 | 75.6% | 76.8% | 70.0% | 77.8% |

| 2019 | 76.2% | 77.4% | 71.3% | 78.5% |

| 2020 | 70.1% | 71.6% | 65.5% | 73.4% |

| 2021 | 72.4% | 74.1% | 69.1% | 77.6% |

| 2022 | 76.3% | 77.5% | 71.9% | 80.2% |

| 2023 | 77.7% | 78.0% | 71.1% | 80.6% |

| 2024 | 77.7% | 78.3% | 72.2% | 80.8% |

Notes: Prime-age refers to workers ages 25 to 54. AIAN refers to American Indian and Alaska Native, and AAPI refers to Asian American and Pacific Islander. Race and ethnicity are mutually exclusive for White, Black, and AAPI workers, but not for AIAN workers (i.e. Black non-Hispanic, Hispanic any race, AAPI non-Hispanic, and AIAN any ethnicity). Race groups are single-race only.

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey basic monthly microdata from EPI Microdata Extracts, Version 1.0.60 (2025); https://microdata.epi.org.

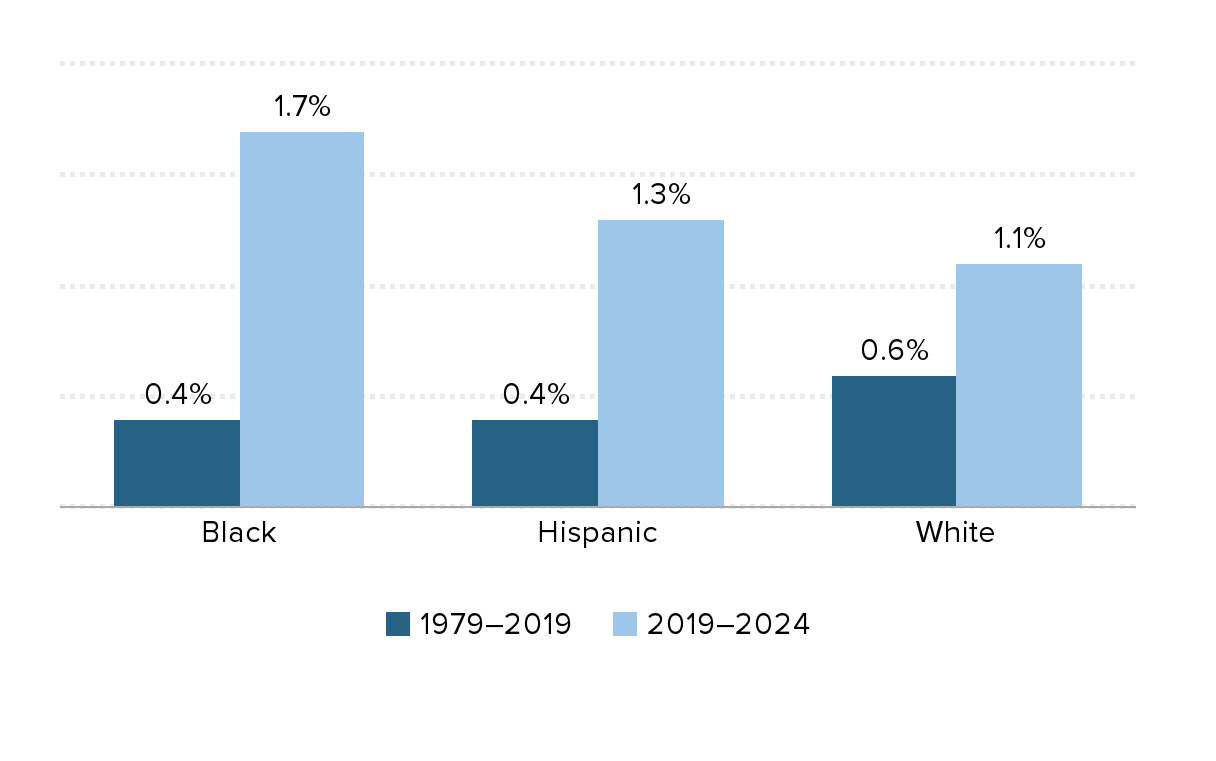

The rapid and sustained labor market recovery also helped deliver stronger wage growth for workers of color (see Figure B). Black workers experienced the fastest wage growth of any group between 2019 and 2024. In fact, Black and Hispanic real wages grew more than three times faster over the last five years than the four decades prior, on an annualized basis. Much of this is explained by low-wage workers (who are disproportionately workers of color) experiencing strong wage growth since 2019, as the tight labor market with low unemployment compelled employers to expand their hiring networks and compete for workers by offering higher wages.

Black and Hispanic workers experienced faster wage growth in the past five years: Annualized real median wage growth for Black, Hispanic, and white workers, select periods

| 1979–2019 | 2019–2024 | |

|---|---|---|

| Black | 0.4% | 1.7% |

| Hispanic | 0.4% | 1.3% |

| White | 0.6% | 1.1% |

Note: Race/ethnicity categories are mutually exclusive (i.e., white non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, and Hispanic any race).

Source: Authors analysis of EPI's State of Working America Data Library.

These historic gains should be protected and continued through a policy regime centered on low unemployment and pro-worker, pro-equity policies. Instead, all of these things are now under threat. Since taking office, President Trump has signed several executive orders centered on deporting migrants, including taking actions that will make it harder for migrants to legally work and support their families in the United States. He also signed orders ending critical diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility programs within the federal government, which were dedicated to promoting goals of racial and gender equity within the economy and beyond.

Further, President Trump has stifled the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) by illegally firing Commissioners Charlotte Burrows and Jocelyn Samuels, who were appointed by President Biden and confirmed by the Senate. As an independent agency, EEOC commissioners are intended to be insulated from presidential interference once nominated and confirmed. These illegal firings have prevented the EEOC from reaching a quorum to hear cases and fulfill its mission to enforce federal laws that prohibit employment discrimination and harassment.

Beyond these executive actions, the Trump administration has engineered an economic climate of chaos by announcing (and seemingly walking back) a temporary freeze of federal assistance and broad-based tariffs against trading partners.

But it’s not just Trump who poses a threat. Republicans in Congress are considering plans to gut the social safety net, including Medicaid, a move that would make economically vulnerable families pay for tax cuts for the wealthy. These efforts are likely to severely limit our capacity to recover quickly from the next economic crisis as well as exacerbate the persistently high levels of poverty that disproportionately burden families and children of color.

These policies don’t just threaten the historic gains for workers of color over the last five years. All workers and their families are now forced to contend with heightened uncertainty and chaos that put their employment and broader economic security at risk. As attacks on public-sector employment continue, and the prospects of a self-inflicted recession rise, it’s likely workers of color will once again be among the first to contend with setbacks, reversing the forward movement of the last five years.

Enjoyed this post?

Sign up for EPI's newsletter so you never miss our research and insights on ways to make the economy work better for everyone.