Jobs report tells two different stories of the November labor market

Below, EPI economists offer their initial insights on the November jobs report released this morning.

From EPI senior economist, Elise Gould (@eliselgould):

Read the full Twitter thread here.

Even with the weaker than expected November payroll numbers, job growth so far has already topped 6.1 million for 2021. As long as Nov is a blip, the 2021 average rate of 555,000 per month still means we are on track for a full recovery by the end of 2022.https://t.co/FqVVDDfXEN

— Elise Gould (@eliselgould) December 3, 2021

What to watch on jobs day: 2021 job growth on pace to exceed 6 million jobs by November

Job growth will likely top 6 million this year by November, putting us well on track for a full recovery by the end of 2022. Ahead of Friday’s release of the jobs report, I want to put the pace of this recovery in perspective compared with the much slower recovery from the Great Recession. Spoiler: If we continue with the average job growth we’ve seen already in 2021—581,600 per month—we would return to pre-pandemic labor market conditions by December 2022 (while also absorbing population growth). This job growth would be at a pace more than twice as fast as the strongest 10-month period in the recovery from the Great Recession (4.9% job growth versus 2.3%).

In October, job growth was 531,000. Even with the slower job growth in late summer due to the Delta-driven five-fold increase in caseloads, the overall pace of the recovery is promising. Back in June, my colleague Josh Bivens and I wrote that restoring pre-COVID labor market health by the end of 2022 would require creating 504,000 jobs each month from May 2021 until December 2022. In 2021 so far, job growth has averaged 581,600 jobs, and it’s been an even greater 665,500 jobs per month since May.

State and local enforcers standing up to protect workers: Misclassifying workers ‘a pattern of deceit’

Series: The New Labor Law Enforcers

State attorneys general, district attorneys, and localities like cities are increasingly key players in protecting workers’ rights. This new series by Terri Gerstein provides snapshots of enforcement and other actions to protect workers’ rights by these new and emerging labor law enforcers at the state and local level. Gerstein is an EPI senior fellow and director of the state and local enforcement project at the Harvard Labor and Worklife Program, who has chronicled the growing influence of these new enforcers.

Recent cases brought by state and local enforcers include a host of violations: construction companies engaging in “a pattern of deceit” to misclassify and underpay workers; unsafe working conditions at Amazon; failure to provide paid sick leave; and the chronic problem of employers misusing interns and not paying for their work.

Here’s an snapshot of some enforcement actions across the country:

Up to 390,000 federal contractors will benefit from a $15 minimum wage starting in January

Below, EPI economist Ben Zipperer responds to the U.S. Department of Labor’s final rule requiring federal contractors to pay a minimum wage of $15 per hour starting January 30, 2022. Zipperer estimates the rule will benefit up to 390,000 federal contractors, half of whom are Black or Hispanic.

States are choosing employers over workers by using COVID relief funds to pay off unemployment insurance debt: Policymakers shouldn’t be afraid to increase taxes on employers to improve unemployment insurance

Because the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing recession led to skyrocketing unemployment rates in early 2020, 23 states were forced to take out federal loans to continue paying out unemployment insurance (UI) benefits. While interest was initially waived on these loans, these debts started to collect interest after Labor Day of 2021. In recent months, many states have chosen to use federal fiscal relief funds given to state and local governments by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act of 2020 and the 2021 American Rescue Plan (ARP) to pay off accumulated UI trust fund debt.

This blog will detail why this is a poor use of federal recovery funds. Our main arguments are:

- Paying off UI trust fund debt accumulated in the past with fiscal relief funds means that these funds are not being used to support current investment or employment,

- Several key areas of state and local government investment have been deprived of funding for over a decade—using ARP relief funds to make up for this past investment deficit would spread the benefits of the fiscal aid much more broadly.

- State and local government employment remains steeply depressed from the COVID-19 economic shock. Restoring these jobs—and the full value of services these workers provided—should be a much higher priority for these governments than paying off UI debt.

- Paying down accumulated trust fund debts should be done by collecting more revenues from the employer payroll taxes earmarked for the UI system. These taxes have been kept far too low for too long and the result has been a dysfunctional UI system in many states.

The Post Office at a crossroads

Politics and special interests, not economic constraints, are what’s keeping the U.S. Postal Service from becoming a hub for affordable banking and other valuable community services in the 21st century. But we’ll need a new regulatory structure and new leadership to move forward.

USPS has a public service mandate to provide a similar level of service to communities across the country regardless of local economic conditions. In addition to daily mail delivery to far-flung locations, the Postal Service maintains post offices even in low-income urban neighborhoods and small towns that lack other basic services. The Postal Service is able to fulfill its mission while keeping postage rates low due to economies of scale.

Once the fixed costs of post offices and delivery are covered, the additional cost of new services is often minimal. If it weren’t prevented from doing so, the Postal Service could take advantage of underused capacity and build on Americans’ trust in the Postal Service to offer new services to the public while bringing needed revenue to the agency. But first we need to jettison a regulatory framework that protects private-sector rivals at the expense of consumers.

Fiscal policy and inflation: A look at the American Rescue Plan’s impact and what it means for the Build Back Better Act

Inflation has jumped up beyond what many expected earlier in this year. While there are plenty of good reasons to think it will begin decelerating by early 2022 and settle into more normal ranges rather than continuing to spiral upward, it has already proven more stubborn than many (well, at least I) expected.

This raises two key questions: Does rising inflation mean critics of the American Rescue Plan (ARP) have been vindicated, as is often claimed lately? And does this mean that the Build Back Better Act (BBBA) currently being debate should be shelved and/or radically trimmed down in size?

The respective answers to these questions are “mostly not” and “absolutely not.”

Quits hit record high in Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey with little change in job openings and hires

Below, EPI senior economist Elise Gould offers her initial insights on today’s release of the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) for September. Read the full Twitter thread here.

After falling sharply in August with the significant rise in COVID caseloads, the job openings rate continued to soften in September. pic.twitter.com/bxk8IWouD8

— Elise Gould (@eliselgould) November 12, 2021

The Build Back Better Act will support 2.3 million jobs per year in its first five years

The Build Back Better Act, while still not a done deal, now has a path toward passage in the House of Representatives, with a vote expected mid-November. The political wrangling to reach this moment has been tortuous. But the promise of the pending bill that could transform millions of lives—with meaningful investments in child care, long-term care, and universal pre-K, among others—is critical for a thriving modern economy that will boost productivity and deliver relief to strained family budgets.

Here, we update a previous analysis to reflect the latest state of the legislation and assess its potential impact on U.S. labor markets. Overall, we estimate that the Build Back Better Act (BBBA) will provide support for 2.3 million jobs per year in its first five years, shown in detail in Table 1, below. Add to this an estimated 772,000 jobs per year supported by the bipartisan infrastructure deal, also referred to as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, passed last Friday in the House, and you get more than 3 million jobs supported per year.

October inflation spike is not driven by economic overheating

Below, EPI director of research Josh Bivens offers his insights on today’s release of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for October, which showed a 6.2% rise compared with a year ago. As Bivens explains, the inflation spike we’ve seen in 2021 is not driven by macroeconomic overheating. Instead, this spike is largely driven by COVID-related factors: a reallocation of spending away from face-to-face services and toward goods combined with supply-chain bottlenecks. Read the full Twitter thread.

Core inflation up less, at 4.6% y-o-y, but, still a large number. And yet the main determinants of this rise still look to me to not include macroeconomic overheating. 2

— Josh Bivens (@joshbivens_DC) November 10, 2021

Alabama is making a costly mistake on COVID-19 recovery funds. Here’s a better path forward.

When the Alabama legislature gathered for a special session in September, it made a short-sighted and costly mistake. Lawmakers chose to allocate $400 million in American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) money—about 20% of Alabama’s federal COVID-19 relief funds—to help finance a $1.3 billion prison construction plan.

Alabama prisons are decrepit, dangerous, and massively overcrowded to such an extent that the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) has sued the state over the unconstitutional conditions. Raiding funds designed to help people and communities recover from pandemic-related economic distress will do nothing to make Alabama more humane and inclusive, particularly when Black Alabamians are three times more likely to be incarcerated than white Alabamians due to discriminatory practices in policing and incarceration.

The state has a better path to build a more sensible criminal justice system and avert a potential federal takeover. New buildings to house the same old problems won’t get us there. Real change will require meaningful changes to sentencing and reentry policies.

Solid job growth in October as the recent surge in the pandemic recedes

Below, EPI economists offer their initial insights on the October jobs report released this morning. After disappointing job growth numbers in August and September, a solid 531,000 jobs were added in October.

What to watch on jobs day: October job growth expected to mildly improve as COVID-19 caseloads recede

Over the last couple of months, the resurgence of the Delta variant has made it abundantly clear that the ebbs and flows of the pandemic continue to exert powerful effects on the labor market. After increasing, on average, over 1 million jobs in June and July, job growth slowed to less than 300,000, on average, for August and September. While COVID-19 caseloads have slowed between September and October, they continue to be higher than experienced in June and July, suggesting that we will see a mild improvement—not a huge windfall—when the latest employment data are released on Friday.

For the reference week of the October jobs data, average daily COVID-19 caseloads stood at 78,987. This is a significant (43.5%) improvement over the average daily COVID-19 caseloads during the September reference week: 139,920. All else equal, this should translate into economic growth, as workers begin to feel it is safer to resume in-person job search and employment and consumers become more willing to purchase in-person services. The decline in October COVID-19 caseloads, however, does not mean we are back to the levels earlier in the summer. October’s levels were over twice as high as the average daily caseloads during the reference week in July (33,711 cases).

Similarly, OpenTable shows mild improvement in restaurant customers between September’s and October’s reference weeks. While seated diners in September were down 12.6% compared with the same week in 2019, the number of diners was down 8.4% in October. Although the 8.4% drop in seating relative to the pre-pandemic period is less than what we saw in September, it is still not as promising as the smaller 5.7% drop in July’s reference week compared to July 2019. This likely means the October labor market did not see the kind of growth we experienced in June or July, but some improvement from the disappointing September level is likely.

The Build Back Better Act’s macroeconomic boost looks more valuable by the day

In previous work, Adam Hersh highlighted how the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and the Build Back Better Act (BBBA) could provide a backstop against the possibility that economic growth slows due to slack in aggregate demand for goods and services in the next couple of years. Over the past few months, a pronounced uptick in inflation convinced far too many that the U.S. economy actually faced the opposite problem of macroeconomic overheating—an excess of aggregate demand.

But late last week, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) released data making it clear that the U.S. economy is not overheating and that aggregate demand support in 2022 and 2023 could be vital to continued economic growth. Given this, the macroeconomic boost provided by the BBBA in coming years could be valuable indeed.

New analyses of minimum wage increases in Minneapolis and Saint Paul are misleading, flawed, and should be ignored

This week, researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis released two analyses of the economic impact of several recent increases in the separate citywide minimum wages in Minneapolis and Saint Paul. The authors of the two separate, but linked, analyses interpret their findings as suggesting that the series of minimum wage increases reduced employment in the Twin Cities, but this conclusion is not supported even by the results presented in their own reports.

The data and methodology used in the study are simply not sufficient to distinguish between the effects of the minimum wage increases and other changes in employment happening around the same time. Even more problematic are the studies’ unsuccessful attempts to estimate effects through 2020, when the study’s methodology is unable to separate the effects of the minimum wage from the devastating impact of the pandemic on the two cities’ service-sector workforces. In fact, the studies’ findings implausibly suggest that the entire decline in restaurant employment during the pandemic is due to the minimum wage increases, as opposed to lockdowns, curfews, and pandemic-related declines in consumer spending on eating out.

Yes, the Build Back Better Act is fully paid for

EPI director of research Josh Bivens took to Twitter to refute critics’ most recent claim that the Build Back Better Act (BBBA) is only “fully paid for” due to accounting gimmicks. The claim, Bivens stresses, is “bad economics,” adding that BBBA is indeed fully paid for. Read the full Twitter thread explaining why below.

Children whose parents couldn’t find decent work? Underserving of a modest unconditional tax credit. Millionaire heirs? Deserving of maintenance of a zero tax rate on inherited capital gains. 2

— Josh Bivens (@joshbivens_DC) November 2, 2021

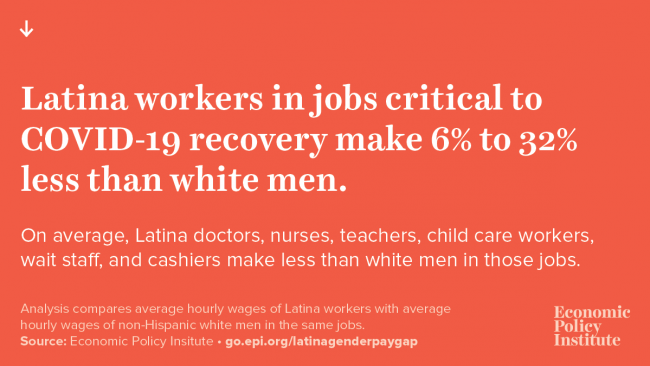

Latina Equal Pay Day: Latina workers remain greatly underpaid, including in front-line occupations

October 21 is Latina Equal Pay Day. Last year, a typical Latina worker who worked full-time, year-round earned only 57 cents for every dollar earned by white, non-Hispanic men. This means that Latinas on average must work nearly 22 months to earn what white, non-Hispanic men earn in 12 months.

The infographics below take a closer look at average hourly wages of Latinas and non-Hispanic white men employed in major occupations at the center of national efforts to address COVID-19, based on our previous analysis of Current Population Survey data from 2014-2019. These occupations include front-line workers in health care and essential businesses like grocery stores, those who have borne the brunt of job losses in the restaurant industry, and teachers and child care workers. We found that Latina workers make between 6% to 32% less than non-Hispanic white men in these occupations.

Few Midwestern states are providing premium pay to essential workers, despite American Rescue Plan funding

Key takeaways

- The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) allocated $195 billion in fiscal recovery funds directly to states.

- One of the key uses of the funds was for premium pay for front-line workers impacted by the pandemic, which would disproportionately benefit Black and Brown workers and women.

- However, only two Midwestern states—Michigan and Minnesota—are using American Rescue Plan funding to provide premium pay (also called “hazard pay”) for low-wage essential workers.

- This breaks down to just 2% of funds allocated to Midwestern states being used for premium pay. Essential workers deserve better.

The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) presents a historic opportunity for state and local governments to shape their region’s economic recovery and also address the long-standing inequities that the pandemic continues to expose and worsen. One straightforward way that ARPA money could be used to combat these inequities is boosting the wages of the disproportionately Black and Brown workers and women who have been on the front lines of the public health and economic crisis. However, few Midwestern states have opted to do so; data on states’ allocation of ARPA funds thus far show few resources being put towards premium pay.

ARPA allocated $195 billion in fiscal recovery funds directly to states, with billions more also directed to counties, cities, tribal governments, and other units of local government. Interim rules developed by the Department of the Treasury designate four allowed uses for ARPA funds: including investments for infrastructure; assistance to households, small businesses, and nonprofits, and industries impacted; propping up state government services impacted by tax shortfalls; and premium pay.

Among the four uses, premium pay in particular would help lift up marginalized workers impacted by the pandemic. Premium pay” (also sometimes called hazard pay, even sometimes called “hero pay” by businesses) for workers “in critical infrastructure sectors who regularly perform in-person work, interact with others at work, or physically handle items handled by others.” This includes jobs in child care, health care, grocery stores, meat processing, transportation, and public health.

Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey reflects a decline in both job openings and hires after Delta variant surge

Below, EPI senior economist Elise Gould offers her initial insights on today’s release of the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) for August. Read the full Twitter thread here.

The fall in job openings and hires for August is consistent with the #JobsReport for the same month and the uptick in separations (due to an increase in quits) is not surprising as covid caseloads increased about five fold between July and August. pic.twitter.com/3b0r194qFw

— Elise Gould (@eliselgould) October 12, 2021

Weak job growth in September as Delta variant leaves its mark

Below, EPI economists offer their initial insights on the September jobs report released today. After a relatively weak August, only 194,000 jobs were added in September.

Cutting the reconciliation bill to $1.5 trillion would support nearly 2 million fewer jobs per year

Congress may have bought itself another month to negotiate over the Biden-Harris administration’s Build Back Better (BBB) agenda, but one thing is clear: Further reducing the scale and scope of the budget reconciliation package unequivocally means the legislation will support far fewer jobs and deliver fewer benefits to lift up working families and boost the economy as a whole.

How much will such compromise cost the U.S. economy? We crunched the numbers to find out what compromising on the BBB plan will mean for every state and congressional district in the United States. If the budget reconciliation package is cut from $3.5 trillion to $1.5 trillion—as Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.V.) has called for—nearly 2 million fewer jobs per year would be supported.

What to watch on jobs day: A seasonal swing in public-sector education employment

On Friday, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) will release September’s numbers on the state of the U.S. labor market. August employment growth came in lower than June or July due in part to the Delta variant spreading quickly. Another sign of weakness in the August job report was the rise of Black unemployment, which remains significantly higher than other groups. The August jobs report showed us, once again, just how much the ebbs and flows of the pandemic are the dominant influence by far on trends in the labor market.

This pronounced August slowdown also came after more than half of all states prematurely ended the pandemic unemployment insurance (UI) programs. All of the pandemic programs ended in early September.

While no longer accelerating, COVID-19 caseloads were still high in mid-September compared with the early summer months, so that may once again slow the recovery. In this jobs report, one indicator I’m going to be paying close attention to is public-sector employment, specifically public-sector education employment.

Overall government employment is still down 790,000 jobs since February 2020—the third largest employment deficit in any economic sector—but this shortfall is entirely in state and local employment and much of those losses were in education employment. Local education employment—think the public K-12 school system—cratered in the spring of 2020, experiencing losses in excess of those suffered in the Great Recession and, as of mid-August, remained 219,600 short of its pre-pandemic level.

Abolish the debt ceiling before it commits austerity again: The GOP used the debt ceiling to force spending cuts in 2011. It can’t be allowed again.

In a political system beset by many stupid and destructive institutions, the statutory limit on federal debt might be the worst. The debt limit:

- Measures no coherent economic value. The measure of debt it targets is not inflation-adjusted, would perversely make the debt situation look worse if there was a reform to Social Security that closed that program’s long-run actuarial imbalance, and ignores trillions of dollars in assets held by the federal government.

- Has no relationship to any economic stressor facing the country. Over the past 25 years, as the nominal federal debt rose from $5 trillion to $22.7 trillion, debt service payments (required interest payments on debt) shrank almost in half, from 3.0% of GDP to 1.8%.

- Can cause real damage if it’s not lifted in the next couple of weeks. It would only take a couple of months of missing federal payments due to the debt ceiling to mechanically send the economy into recession—and that’s without assessing damage it would cause from financial market fallouts.

- Has been used time and time again to enforce misguided austerity policies. The 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA) grew directly out of a GOP Congress threatening to not raise the debt ceiling absent spending cuts. The BCA provided an anti-stimulus about twice as large as the stimulus provided by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA—commonly known as “The Recovery Act”) and is largely responsible for the sluggish recovery from the Great Recession.

Given all of this, the debt ceiling should be abolished or neutralized in absolutely any way politically possible. It serves no good economic purpose and plenty of malign ones. Below we expand on these points.

Two-thirds of low-wage workers still lack access to paid sick days during an ongoing pandemic

According to a new report released yesterday from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), just over three-quarters (77%) of private-sector workers in the United States have the ability to earn paid sick time at work. But, as shown in Figure A below, access to paid sick days is vastly unequal, disproportionately denying workers at the bottom this important security. The highest wage workers (top 10%) are nearly three times as likely to have access to paid sick leave as the lowest paid workers (bottom 10%). Whereas 95% of the highest wage workers had access to paid sick days, only 33% of the lowest paid workers are able to earn paid sick days.

Low-wage workers are also more likely to be found in occupations where they have contact with the public—think early care and education workers, home health aides, restaurant workers, and food processors. Workers shouldn’t have to decide between staying home from work to care for themselves or their dependents and paying rent or putting food on the table. But that is the situation our policymakers have put workers in. Meaningful paid sick leave legislation is incredibly important for low-wage workers and their families and important to reduce the spread of illness. At the same time, access to paid sick days has positive benefits to employers as it reduces employee turnover with no impact on employment.

High-wage workers have paid sick days; most low-wage workers do not: Share of private-sector workers with access to paid sick days, by wage group, 2021

| Category | Share of workers who have access to paid sick days |

|---|---|

| Bottom 25% | 52% |

| Second 25% | 81% |

| Third 25% | 88% |

| Top 25% | 94% |

| Bottom 10% | 33% |

| Top 10% | 95% |

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, National Compensation Survey 2021

All pain and no gain: Unemployment benefit cuts will lower annual incomes by $144.3 billion and consumer spending by $79.2 billion

Congress and the Biden-Harris White House have let expanded unemployment benefits expire in the middle of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, even while employment is still well below pre-pandemic levels. As a result, annual incomes across the U.S. will fall by $144.3 billion and annualized consumer spending will drop by $79.2 billion, according to the best available evidence on the effects of recent unemployment benefit cuts.

In March 2020, as the economic impact of the pandemic spread quickly, Congress critically expanded unemployment insurance (UI) benefits by providing $600 (and later, $300) monthly supplements, extending benefit periods, and making previously excluded workers—such as independent contractors and those with low incomes—eligible for UI.

However, about half of states prematurely terminated these programs between June and late July 2021, and then, by letting the federal law expire in September, Congress and the White House cut off pandemic UI entirely. In total, more than 10 million workers lost all of their unemployment benefits because of either the state-level program terminations or the September program expiration.Read more

Pandemic-related economic insecurity among Black and Hispanic households would have been worse without a swift policy response

The Census Bureau report on income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in 2020 reveals an expected shock to median household income relative to 2019 resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic and recession. Across all racial and ethnic groups, median household income either declined or was statistically unchanged from the previous year.

While Census cautions that the 2020 income estimates may be overstated due to a decline in response rates for the survey administered in March of this year, real median income declined 4.5% among Asian households (from $99,400 to $94,903), 2.6% among Hispanic households (from $56,814 to $55,321), 2.7% among non-Hispanic white households (from $77,007 to $74,912), and was statistically unchanged for Black households (from $46,648 to $46,600) as seen in Figure A.

In 2019, Black American households finally surpassed the median income peak they achieved prior to the Great Recession of 2008-2009. In 2020, however, the pandemic recession cut that long recovery short.

In 2020, the median Black household earned just 61 cents for every dollar of income the median white household earned (unchanged from 2019), while the median Hispanic household earned 74 cents (unchanged from 2019).

Black and brown workers saw the weakest wage gains over a 40-year period in which employers failed to increase wages with productivity

Key takeaways:

- Wage growth for typical Black and Hispanic workers fell far short of growth for white workers over the past 40 years.

- Increasing income inequality overall and racial discrimination in the labor market both play a role in limiting wage gains for Black and Hispanic workers.

- Women’s median wages have increased since 1979 but still lag those of men. Gains among women have not been equally shared, with white women seeing the largest wage increases.

Policy recommendations:

- Create “high-pressure” labor markets by running the economy hot through expansionary macroeconomic policies; prioritizing low unemployment will help spur job growth as well as wage growth, especially for Black workers.

- Prioritize anti-discrimination enforcement.

- Pass the Raise the Wage Act and the Richard L. Trumka PRO Act. These would have a range of positive benefits for workers across the board, and especially for women, Black, and Hispanic workers.

Increasing income inequality has been at the forefront of economic policy conversations in the United States since at least the 2008 financial crisis. The roots of that inequality stretch back much further, though. Growing employer opposition to unions and the shift from manufacturing toward finance as a major growth industry over many decades has resulted in a separation between worker pay and productivity that has persisted to this day.

There has been growing concern about the wage stagnation faced by the typical American worker, and increasing attention paid to the need to rectify this—to ensure that workers reap the gains associated with their increased productivity.

By the numbers

Wage growth by race/ethnicity, 1979–2020

- White workers: 30.1 %

- Black workers: 18.9%

- Hispanic workers: 16.7%

The productivity–pay gap

- Productivity growth, 1979–2020: 61.7%

- Typical worker wage growth, 1979–2020: 23.1%

However, there has not been as much attention paid to the distinct divisions that exist even among the generally undercompensated working class. While the typical worker has not seen their fair share of wage increases relative to the increase in productivity over the past 40 years, Black and Hispanic workers saw even smaller wage gains relative to their white counterparts.

These racial disparities in pay add another dimension to conversations about gaps between pay and productivity, and about income inequality in general. While policies designed to link the typical worker’s pay more closely with productivity are necessary to reduce income inequality overall, the persistence of disparities even within the working class shows us that targeted policies will be required in addition if we want to achieve the goal of true equity across the board.Read more

Immigration reform would be a boon to U.S. economy and must be part of the $3.5 trillion budget resolution: Senate parliamentarian would be wrong to rule otherwise

A path to citizenship for unauthorized immigrants is not “merely incidental” to the American economy—it’s primarily intended to provide labor and political rights and create the positive economic gains that come with it.

That’s why the Senate parliamentarian should rule to include immigration reform in the current $3.5 trillion budget resolution, which aims to provide a pathway to citizenship for many of the current unauthorized immigrants residing in the United States.

The Senate parliamentarian heard arguments about the inclusion of a pathway to citizenship from Democratic legislators on Friday, and on the same day, the House Judiciary Committee posted its version of the immigration provisions for the budget resolution. The following Monday, the Judiciary Committee voted to approve the immigration language, allowing it to be included in the overall budget resolution. Included in it are provisions that would put immigrant Dreamers, Temporary Protected Status and Deferred Enforced Departure recipients, farmworkers and certain workers deemed to have been employed in “essential” occupations during the pandemic onto a path to citizenship, as well as recapture unused immigrant visas from prior years, among other reforms.

Using reconciliation to pass these reforms would allow the Democrats to bypass Senate Republicans using the filibuster to prevent the legislation from passing. The Democrats’ budget resolution is an essential piece of legislation that must pass: It has the potential to make historic improvements in bolstering the social safety net, fighting climate change, and creating jobs. However, if it leaves millions of unauthorized immigrants without the civil, human, and workplace rights they would gain if they had a path to citizenship, the plan would fail to achieve its full potential.

Social insurance programs cushioned the blow of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020

Even in normal times, public safety net spending and social insurance programs are effective policy tools to reduce poverty and alleviate the economic distress of families. Census data released today also show that these programs kept tens of millions of people from severe economic deprivation during the first half of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Remarkably, poverty rates were significantly lower last year than they were in 2019, after accounting for the scale of public assistance provided in 2020.

The poverty rate reduction highlights how much poverty the nation and its policymakers tolerate is a choice. It should not have taken a pandemic to make us realize this.

Last year, Economic Impact Payments (stimulus checks) and unemployment insurance (UI) benefits played larger than usual roles in reducing poverty. The Census Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) data show that the first two Economic Impact Payments and UI benefits reduced poverty by 11.7 and 5.5 million people, respectively (see Figure A).

By the Numbers: Income and Poverty, 2020

Jump to statistics on:

• Earnings

• Incomes

• Poverty

• Policy / SPM

This fact sheet provides key numbers from today’s new Census reports, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2020 and The Supplemental Poverty Measure: 2020. Each section has headline statistics from the reports for 2020, as well as comparisons with the previous year. This fact sheet also provides historical context for the 2020 recession by analyzing changes between the last business cycle peak in 2019 to 2007 (the final year of the economic expansion that preceded the Great Recession), and to 2000 (the prior economic peak). All dollar values are adjusted for inflation (2020 dollars). Because of a redesign in the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC) income questions in 2013, we imputed the historical series using the ratio of the old and new method in 2013. All percentage changes from before 2013 are based on this imputed series. We do not adjust for the break in the series in 2017 due to differences in the legacy CPS ASEC processing system and the updated CPS ASEC processing system, but these differences are small and statistically insignificant in most cases.