No way out: Older workers are increasingly trapped in crummy jobs and unable to retire: Growing disparities in work and retirement in 30 charts

“I prayed to God that he would take care of my health, body, mind, soul, and spirit.” Those words came from Libia Vargas De Dinas, a 72-year old diabetic janitorial worker who worked in a Florida county courthouse and got stuck in a holding cell by accident for three days in February.

At Christmas time last year, an 82-year-old Walmart cashier was finally able to retire after a viral TikTok video and GoFundMe campaign netted him over $100,000. A kind customer posted the TikTok video, saying, “I was astounded seeing this little older man still grinding working 8- to 9-hour shifts.”

Do these stories illustrate America’s retirement divide or are they oddities?

The evidence compiled in our recently released Older Workers and Retirement Chartbook suggests the former, though the story is complex and multilayered.

Once workers reach older ages, especially Black and brown workers, those who are not financially able to retire must accept low wages and poor working conditions because they know they have little chance of finding a better job, or any job at all, if they lose employment.

Because of this, for most of these workers, working longer does not prevent poverty in retirement, though it may postpone it for some time. Many are left with no choice other than claiming Social Security benefits early, leading to reduced Social Security benefits and increasing downward mobility and poverty in retirement. They have no way out.

The chartbook—produced by The New School’s Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis and the Economic Policy Institute which documents an array of disparities in more than 30 charts—shines many spotlights on this grim reality. It provides evidence that millions are unable to retire due to financial stress while others are pushed into involuntary premature “retirement” even if they don’t have enough money to make ends meet.

Nearly half of older Americans are financially unready for retirement—many on the precipice of poverty. Most workers have little, if anything, in their retirement accounts; the median retirement account balance for Americans approaching retirement age is only $10,000. If nothing changes, older Americans may increasingly need to hope for random acts of kindness and GoFundMe pensions.

The two-way connection between bad jobs and retirement financial precarity

Over the past two decades, older workers have become an increasingly significant share of the labor force. In the economic recovery after the Great Recession of 2008–2009, four in 10 Americans ages 55 or older were in the labor force—the highest participation rate in half a century. As of 2020, these older workers made up 23.6% of the total U.S. workforce, the highest portion on record.

Why are so many older Americans unable to retire and so many working into old age to survive? For many, the answer isn’t “because they want to.” Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, more than 50% of low-income older households ages 55–64 were financially fragile—up dramatically from the 35% at risk in 1992. This measure of precarity, the chartbook explains, is based on their debt burdens, housing costs, and the savings they had available to access in an emergency.

Financial fragility is not random. When broken down by race and ethnicity, we see significant differences in precarity: 57.0% of older Black households and 50.7% of older Hispanic households were financially fragile, compared with 33.4% of older white households. “The connection between work and retirement insecurity is a two-way street. Bad jobs lead to bad retirements, but retirement insecurity also forces older workers to accept bad jobs,” the chartbook explains.

Factors like race and ethnicity, gender, education, sexual identity, and disability affect Americans’ socioeconomic status throughout their working life and these disparities tend to be magnified along the life cycle.

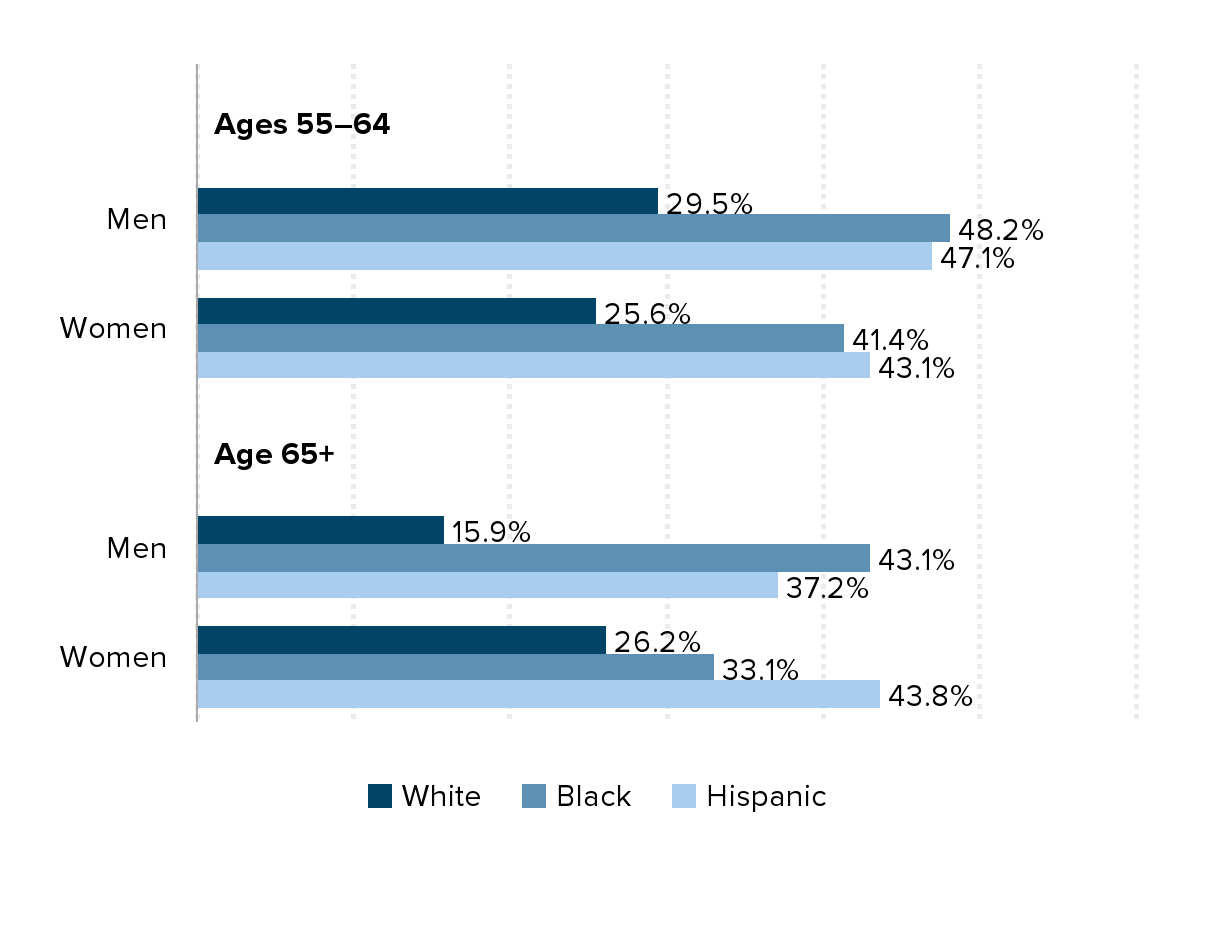

And making matters worse, older workers perform more physically taxing work than might be expected, and older Black and Hispanic workers are much more likely than white workers to have physically demanding jobs.

Older Black and Hispanic workers are much more likely than older white workers to have physically demanding jobs: Share of older workers in physically demanding jobs, by race and ethnicity, gender, and age, 2018

| Share of workers in physically demanding jobs | White | Black | Hispanic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 29.5% | 48.2% | 47.1% |

| Women | 25.6% | 41.4% | 43.1% |

| Men | 15.9% | 43.1% | 37.2% |

| Women | 26.2% | 33.1% | 43.8% |

Notes: Workers are in a physically demanding job if they answered that their job requires “lots of physical effort” “all” or “most” of the time. Hispanic refers to Hispanic of any race, while white and Black refer to non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic Blacks.

Workers are in a physically demanding job if they answered that their job requires “lots of physical effort” “all” or “most” of the time. Hispanic refers to Hispanic of any race, while white and Black refer to non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic Blacks. The sample includes full- and part-time workers ages 55 and older participating in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) survey.

Source: Economic Policy Institute (EPI) and Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis (SCEPA) analysis of Health and Retirement Study data (RAND 2022; University of Michigan 2022).

How job and labor market disparities hinder retirement access

Lack of access to retirement plans is one of the major causes of insufficient retirement assets among older workers and retirees. How many older Americans approaching retirement have a decent retirement plan? Far fewer than you might think.

Only 57% of older workers (ages 55–64) and 53% of prime-age workers (ages 25–54) participate in an employer-based retirement plan, and this share plunges to 25% for workers ages 65 and older. Lack of access is the biggest factor depressing worker participation in retirement plans.

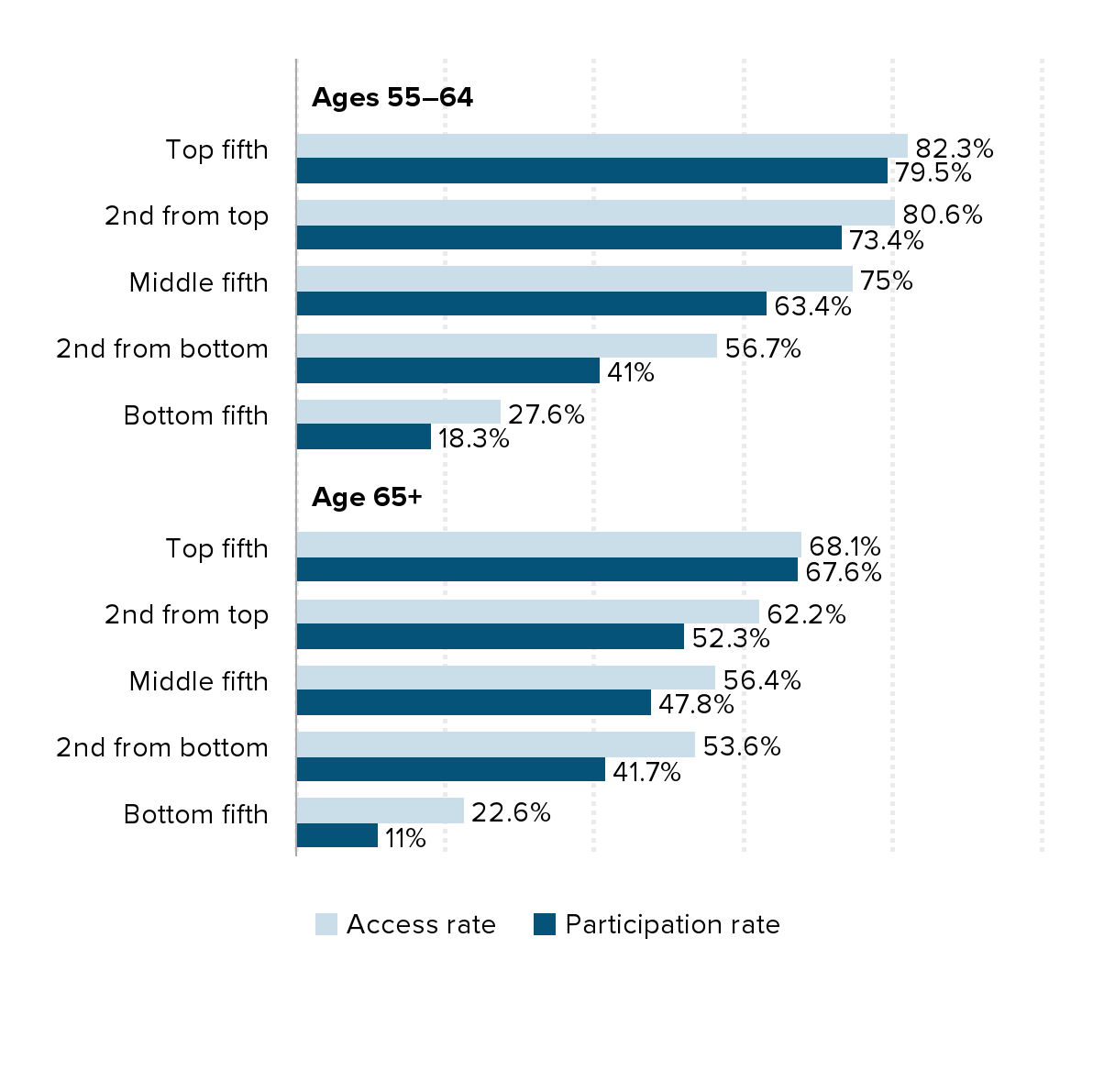

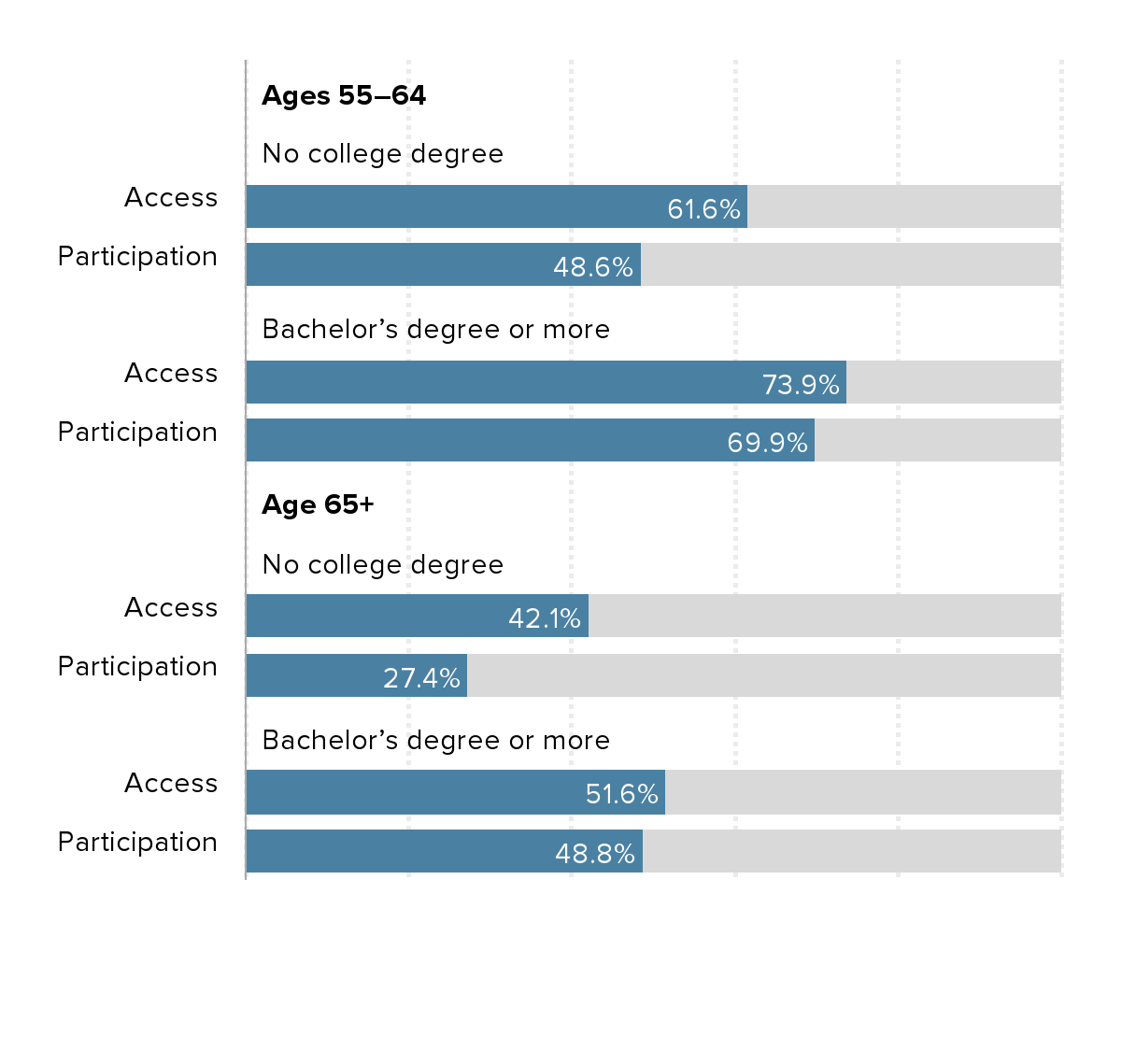

Societal inequities appear in who has access to plans and who doesn’t. For example, one chart below (2F) shows that high-earning older workers are three times as likely as low-earning older workers to have access to a retirement plan. Likewise, older workers without a bachelor’s degree or more education are “much less likely than their college-educated peers to have access to and participate in a retirement plan,” another chart below (2C) shows. While seven in 10 workers ages 55–64 with a bachelor’s degree have a retirement plan, less than half (48.6%) of their counterparts without a bachelor’s degree have this opportunity. In short, the very workers who need greater retirement security after a lifetime of lower earnings are the people left out in the cold in old age.

High-earning older workers are three times as likely as low-earning older workers to have access to a retirement plan: Share of older workers who have access to and participate in a retirement plan at a current job, by earnings group and age, 2019

| Access rate | Participation rate | |

|---|---|---|

| Top fifth | 82.3% | 79.5% |

| 2nd from top | 80.6% | 73.4% |

| Middle fifth | 75.0% | 63.4% |

| 2nd from bottom | 56.7% | 41.0% |

| Bottom fifth | 27.6% | 18.3% |

| Top fifth | 68.1% | 67.6% |

| 2nd from top | 62.2% | 52.3% |

| Middle fifth | 56.4% | 47.8% |

| 2nd from bottom | 53.6% | 41.7% |

| Bottom fifth | 22.6% | 11.0% |

Notes: Retirement plans include traditional defined benefit pension plans and retirement savings accounts such as 401(k)s.

Retirement plans include traditional defined benefit pension plans and retirement savings accounts such as 401(k)s. The sample includes survey respondents and spouses or domestic partners who are employees or self-employed workers (which would include small business owners). Participants in a plan are workers who answered “yes” to a question about whether they were included in any “pension, retirement, or tax-deferred savings plans” connected with their job (not including IRA or Keogh plans) and workers whose spouse or partner answered “yes” for them. Workers with access to a plan are workers who answered “yes” to questions about whether their employer offered any such plans and whether they were eligible to be included in any of those plans and workers whose spouse or partner answered “yes” for them.

Source: Economic Policy Institute (EPI) and Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis (SCEPA) analysis of Survey of Consumer Finances 2019 microdata (Federal Reserve 2022a).

Older workers without a college degree are less likely to have access to and participate in a retirement plan: Share of older workers who have access to and participate in a retirement plan at a current job, by educational attainment and age, 2019

| Yes | No | |

|---|---|---|

| Access | 61.6% | 38.4% |

| Participation | 48.6% | 51.4% |

| Access | 73.9% | 26.1% |

| Participation | 69.9% | 30.1% |

| Access | 42.1% | 57.9% |

| Participation | 27.4% | 72.6% |

| Access | 51.6% | 48.4% |

| Participation | 48.8% | 51.2% |

Notes: Retirement plans include traditional defined benefit pension plans and retirement savings accounts such as 401(k)s.

Retirement plans include traditional defined benefit pension plans and retirement savings accounts such as 401(k)s. The sample includes survey respondents and spouses or domestic partners who are employees or self-employed workers (which would include small business owners). Participants in a plan are workers who answered “yes” to a question about whether they were included in any “pension, retirement, or tax-deferred savings plans” connected with their job (not including IRA or Keogh plans) and workers whose spouse or partner answered “yes” for them. Workers with access to a plan are workers who answered “yes” to questions about whether their employer offered any such plans and whether they were eligible to be included in any of those plans and workers whose spouse or partner answered “yes” for them.

Source: Economic Policy Institute (EPI) and Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis (SCEPA) analysis of 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances microdata (Federal Reserve 2022a).

Compared with other wealthy countries, the United States relies more on employers to voluntarily provide benefits to supplement Social Security, a patchwork retirement system that became even more frayed when private-sector employers began switching from traditional pensions to 401(k) plans in the 1980s—thus shifting most of the cost and all of the risk of these benefits onto workers. This happened around the same time that gradual cuts to Social Security benefits were enacted, a process that is still underway. Despite these cuts, Social Security remains by far the most important source of income for people ages 65 and older, with four in 10 seniors—one-fourth of whom are still working—relying on Social Security payments for at least half their income.

Many workers were not just losing access to secure retirement benefits, they were also losing access to good jobs. The erosion of labor standards and policies that hindered workers’ ability to collectively bargain for better wages and working conditions have left many older workers stuck in bad jobs with no path to retirement.

Policymakers must address this broken system in which half of older Americans are financially precarious. Expanding Social Security and supplementing it with a universal retirement plan must become a top policy priority, as must improving labor standards and workers’ rights. The economic and human costs of not repairing this fracturing world of older workers and retirement are immense and unacceptable. The Older Workers and Retirement Chartbook documents these urgent disparities posing immense challenges that policymakers must confront now.

On May 17 at 2:00 p.m. Eastern, EPI will host a virtual event that will shine a light on this problem and outline policy recommendations to alleviate the plight of older workers. Register here.

Enjoyed this post?

Sign up for EPI's newsletter so you never miss our research and insights on ways to make the economy work better for everyone.