Most minimum wage studies have found little or no job loss

There is always a great deal of political heat around minimum wage increases, largely driven by concerns about job losses. After a minimum wage increase, the story goes, many employers will not be able to afford to pay their workers the new higher minimum wage and will therefore shrink their payrolls. If these job losses are large enough, they could even swamp the higher wages and lead to lower overall wage income for the entire group of affected workers.

Actual evidence shows that this narrative is largely wrong. A new review that I co-authored with Arindrajit Dube finds that most minimum wage studies find no job losses or only small disemployment effects. In other words, the vast majority of minimum wage research implies that minimum wage policies have unambiguously raised the total earnings of low-wage workers.

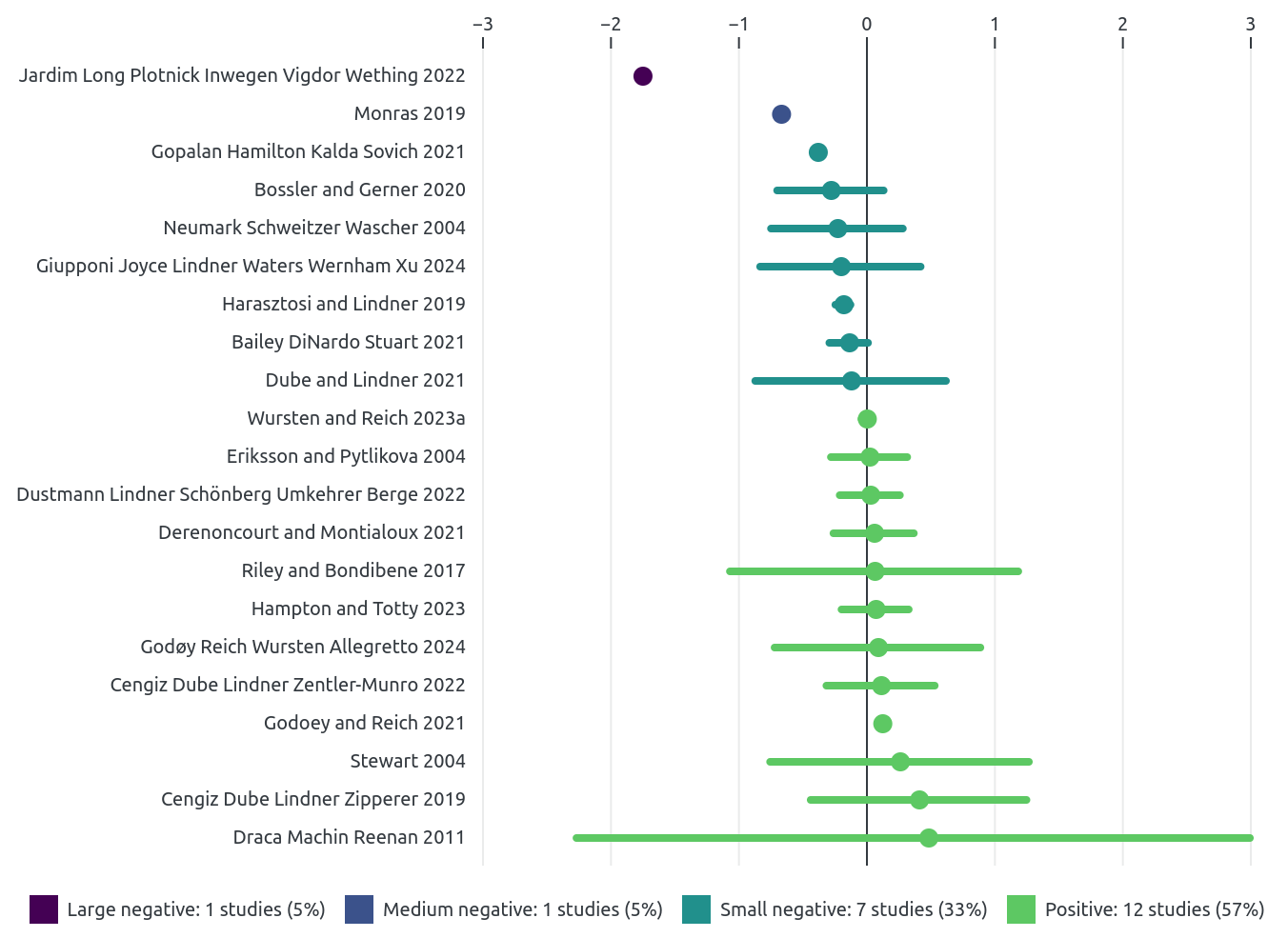

This conclusion is strengthened by focusing on the studies that examine broad groups of low-wage workers or the overall workforce, not just narrow segments like teenagers. As the figure below shows, the median employment response is essentially zero among these more comprehensive studies, with 90% of these studies finding no or only small disemployment effects.

Most minimum wage studies find little-to-no effect on employment: Own-wage elasticities of employment from 21 minimum wage studies covering broad groups of low-wage workers

Note: The own-wage elasticity (OWE) of employment is the percent change in employment for a given percent change in the average wage due to a minimum wage increase. The OWE estimate ranges are “large negative” (less than -0.8), “medium negative” (greater than or equal to -0.8 but less than -0.4), “small negative” (greater than or equal to -0.4 but less than 0.0), and “positive” (greater than or equal to 0.0).

Source: All published studies covering the "overall workforce" from Arindrajit Dube and Ben Zipperer (2024), Minimum wage own-wage elasticity repository, Version 1.0.0.

The new review standardizes the estimates of each study by measuring employment responses relative to how much actual wages rose as a result of minimum wage increases. Earlier reviews of minimum wage research often mixed different types of employment estimates and ignored how much the minimum wage was actually raising wages. The findings were difficult to interpret and not useful to those trying to predict the effects of a prospective minimum wage increase. In particular, these other reviews produced results that could not directly answer the question of whether any job loss they measured was very small or very large, or even whether low-wage workers as a group saw increases in annual earnings after a minimum wage increase.

In addition to providing more helpful estimates from minimum wage studies, the new review is accompanied by an online repository of the underlying data. For every study published since 1992, the repository contains a representative estimate of the employment response for a given wage increase due to minimum wage changes. The repository is a living document and will continue to be updated in order to provide the most current view of the evidence.

Older research found more sizable disemployment effects. But with improvements in research methodology over time, the conclusions of studies have shifted dramatically in the last 15 years. The median employment response to wage increases for studies published since 2010 is very close to zero.1

Minimum wage policies are one of the most well-studied topics in economic research, and the overwhelming conclusion is that minimum wage increases to date have successfully raised the pay of low-wage workers. Conversely, our failure to raise minimum wages–particularly the national minimum wage, which has fallen 29% in inflation-adjusted terms in the past 15 years–has suppressed wages for millions of low-wage workers trying to make ends meet.

Notes

1. See Figure 7 of the review, which also shows that the median own-wage elasticity of employment for studies published between 2010 and 2024 is -0.04.

Enjoyed this post?

Sign up for EPI's newsletter so you never miss our research and insights on ways to make the economy work better for everyone.