Inflation, minimum wages, and profits: Protecting low-wage workers from inflation means raising the minimum wage

There are two main debates about what to do about inflation. One is mostly good-faith (if highly contested): It concerns the actions of the Federal Reserve. Another is mostly bad-faith: It uses the existence of elevated inflation as a cudgel against any progressive policy change and as a justification for long-standing ideological priorities. This is most visible in fiscal policy debates, with some people claiming simultaneously that spending must be restrained (a contractionary move in fiscal policy), but taxes must be cut (an expansionary move).

This bad-faith will certainly rear its head in debates on attempts to move forward on stronger labor standards as well—say by increasing the federal minimum wage. Even under normal circumstances, opponents of minimum wage increases claim that they will be inflationary, so they will almost certainly exaggerate these effects today. In this blog post, I make the following points about the relationship between minimum wages and inflation:

- Faster inflation makes it more important, not less, to raise the federal minimum wage. Every year lawmakers don’t raise the minimum wage is a year that they have effectively cut the purchasing power and living standards of this country’s lowest wage workers.

- Even under a worst-case inflation scenario where every penny in extra pay that results from moving the federal minimum wage to $15 by 2027 is passed on in the form of higher prices, the result would be a five-year stretch of inflationary pressure equal to 0.1% per year (or about 1/100th of the increase we’ve seen since 2021), then the inflationary effect would return to zero.

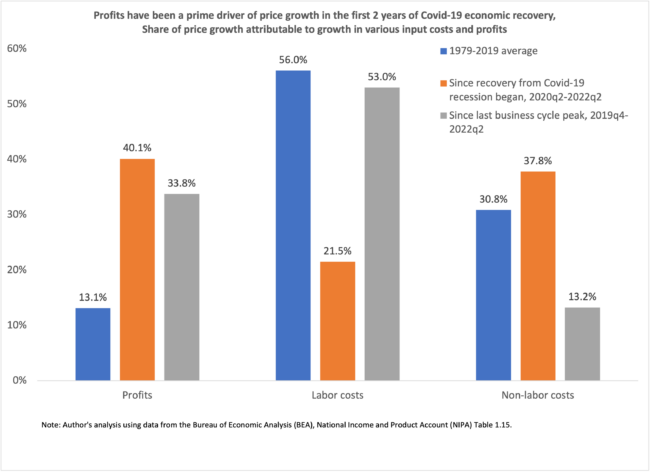

- Even this extremely mild inflation could be substantially blunted by other margins of adjustment to a higher minimum wage—including a retreat from today’s still sky-high profit margins. During normal times, profits account for about 13% of the price of goods and services, but since recovery from the COVID-19 recession began in the second quarter of 2020, rising profit margins have accounted for roughly 40% of the rise in prices. When these margins normalize, there will be ample room for noninflationary wage growth.

Faster inflation makes it more important to raise the minimum wage

Every year that the minimum wage’s value is not raised, it is effectively cut in inflation-adjusted terms. These inflation-driven cuts can snowball quickly, even during stretches of time without particularly fast inflationary outbursts. But when inflation is higher than normal, the real value of the minimum wage can be absolutely crushed if lawmakers don’t act. In the last two years alone, the minimum wage’s purchasing power has dropped by 12.2%—a massive hit to the living standards of working people.

In the 1980s, when inflation was substantially faster than it has been during most of the past 35 years, the federal minimum wage stood frozen at $3.35 between January 1981 and April 1990. Over that time, inflation cut the minimum wage’s value by 46%.

Arguing that the federal minimum wage should only be raised after the current inflationary outbreak is far in the past is arguing that low-wage workers should have no serious protection against the damage to living standards being done by today’s price growth.

Minimum wage increases have trivial effects on inflation

Some claim to worry that raising the minimum wage might exacerbate our current inflation problem. This is not a serious concern. Consider the Raise the Wage Act, which would raise the minimum wage to $15 in five steps by 2027 and would be indexed to growth in median wages thereafter. If every penny of this higher minimum wage fed directly into higher prices—that is, none of it was financed by higher productivity or lower profits—the move to $15 would create a one-time step-increase in the overall price level of less than 0.5%. Spread over five years, this implies an average boost to inflation of less than 0.1% per year, after which it would fade to near-zero. This is completely trivial. Over the past two years, inflation has run at a rate about 100 times faster than this.

The math on this is relatively straightforward. As part of our analysis of previous versions of the Raise the Wage Act (and other minimum wage increases), we estimate the increase in the total wage bill generated by the higher minimum wage. That is, we multiply the number of workers affected by raising the minimum wage from its current level to $15 and then we estimate the average increase in wages they receive. This includes an estimate of “spillover” effects on workers who earn a bit above the new value of the minimum wage, and we assume no job loss stemming from these increases—both of which make our estimate of the effect on the total wage bill larger than it would be otherwise.

We’re currently refining our model to account for the inflation of the past year and the states that have passed laws that will raise their workers’ wages in the same period as the Raise the Wage Act would take effect. These new estimates (though not totally final) indicate roughly a $50–75 billion boost (in 2021$) to the overall wage bill in 2027. An extremely conservative estimate of personal consumption expenditures in 2027 (also expressed in 2021$) is $16.5 trillion (this assumes they grow 1% per year for the next 5 years). This means that the full $50–75 billion boost to the wage bill—if it was financed entirely by price increases—would increase the price level of personal consumption expenditures by roughly 0.3–0.4% by 2027. Importantly, this increase would be spread over the five years before 2027, so inflation would rise by less than 0.1% per year.

Other margins—particularly corporate profits—can absorb this small price pressure

Importantly, even this small increase isn’t guaranteed to happen. Past research has shown that many margins besides higher prices can be used to absorb higher minimum wages. Productivity might increase or profits might fall, for example.

On this latter margin—lower profits—it’s important to note that there is a lot of room for them to absorb the minimum wage hike without feeding through to higher prices. For example, profit margins are up nearly 30% relative to pre-pandemic peaks, and these profit spikes explain roughly 40% of the rise in prices over the recovery. Even in normal times, increased profits contribute to inflation, but in this recovery, the share of inflation that is explained by increased profits is more than three times their normal amount. In short, lower profit margins are a huge potential absorber of any price pressures in coming years—particularly those as small as what a minimum wage increase would impose.

The figure below shows the share of price changes accounted for by unit labor costs, nonlabor costs, and profits over various time periods. Between 1979 and 2019, profits accounted for 13% of price increases and unit labor just a bit under 60%. Since the recovery from the COVID-19 recession began in the middle of 2020, profits account for 40% of the increase—three times their normal contribution. Even compared with the pre-COVID business cycle peak at the end of 2019, the growth of profits accounts for two-and-half times their normal contribution to price growth—right around 34%.

The lesson of this figure is clear: If we’re going to start looking at income sources that need to be restrained to keep inflation in check, we should look to corporate profits, not the wages of America’s lowest-paid workers.

Enjoyed this post?

Sign up for EPI's newsletter so you never miss our research and insights on ways to make the economy work better for everyone.