Sections

Wages have been stagnant for a generation despite sizable increases in overall productivity, incomes, and wealth. For instance, our nation’s output of goods and services per hour worked (productivity, net of depreciation) grew 64 percent from 1979 to 2014, while the inflation-adjusted hourly wage of the typical worker rose by just 6 percent.1 The single largest factor suppressing wage growth for middle-wage workers has been the erosion of collective bargaining.

- The decline of collective bargaining has affected nonunion workers in industries or occupations that previously had extensive collective bargaining because their employers no longer raise wages toward the union-set standard as union membership rates decline.

- The decline of collective bargaining through its impact on union and nonunion workers can explain one-third of the rise of wage inequality among men since 1979, and one-fifth among women.2

American workers want unions

We know that many more workers want collective bargaining than are able to benefit from it—and that the desire for collective bargaining has increased greatly since the 1980s.3 For instance, polling in 2005 showed that a majority of nonunion nonmanagerial workers would vote for union representation if they could. In contrast, polling in the mid-1980s suggested that roughly 30 percent of nonunion nonmanagerial workers would have voted for union representation. The bottom line is that if workers (both union and nonunion) were provided the union representation they desired in 2005, the nonmanagerial workers’ unionization rate would have been about 58 percent. The gap between actual and desired union representation is far higher in the United States than in other advanced nations.

Why is union membership in decline?

In the last two decades, private-sector employer opposition to workers seeking their legal right to union representation has intensified. Compared with the 1990s, employers are more than twice as likely to use 10 or more tactics in their anti-union campaigns, with a greater focus on more coercive and punitive tactics designed to intensely monitor and punish union activity. Employers have increased their use of more punitive tactics (“sticks”) such as plant closing threats and actual plant closings, discharges, harassment, disciplinary actions, surveillance, and alteration of benefits and conditions. At the same time, employers are less likely to offer “carrots,” such as granting of unscheduled raises, positive personnel changes, inducements, special favors, social events, promises of improvement, and employee involvement programs.4

The benefits of collective bargaining are significant

- The union wage premium—the percentage-higher wage earned by those covered by a collective bargaining contract, adjusted for workers’ education, age, and other characteristics—is 13.6 percent overall.

- Unionized workers are 28.2 percent more likely to be covered by employer-provided health insurance and 53.9 percent more likely to have employer-provided pensions, and also enjoy more paid time off with their families.

- Collective bargaining raises the wages and benefits more for low-wage workers than for middle-wage workers and least for white-collar workers, thereby lessening wage inequality.

- Collective bargaining also raises wages and benefits more for black, Asian, Hispanic, and immigrant workers, thereby lessening race/ethnic wage gaps.

- The decline of unions has affected middle-wage men more than any other group and explains about three-fourths of the expanded wage gap between white- and blue-collar men and over a fifth of the expanded wage gap between high school– and college-educated men from 1978 to 2011.5

Collective bargaining and the productivity–wage gap

- The states where collective bargaining eroded the most since 1979 had the lowest growth in middle-class wages and the largest gap between rising productivity growth and middle-class wage growth.6

Decline in union membership and the squeeze on the middle class

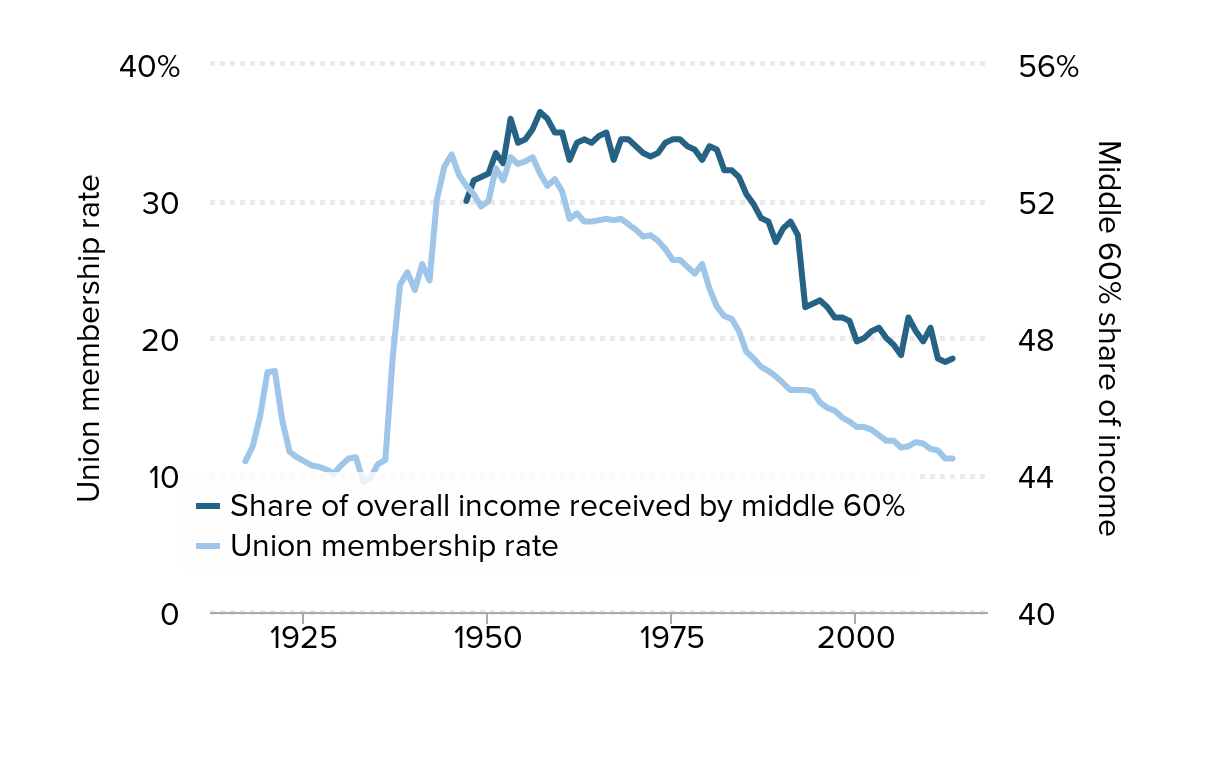

As union membership rates have declined, so has the share of income enjoyed by the middle 60 percent of households, as shown in the below figure.

Union membership rate and share of income going to the middle 60% of families

| Union membership rate | Share of overall income received by middle 60% | |

|---|---|---|

| 1917 | 11.0% | |

| 1918 | 12.1% | |

| 1919 | 14.3% | |

| 1920 | 17.5% | |

| 1921 | 17.6% | |

| 1922 | 14.0% | |

| 1923 | 11.7% | |

| 1924 | 11.3% | |

| 1925 | 11.0% | |

| 1926 | 10.7% | |

| 1927 | 10.6% | |

| 1928 | 10.4% | |

| 1929 | 10.1% | |

| 1930 | 10.7% | |

| 1931 | 11.2% | |

| 1932 | 11.3% | |

| 1933 | 9.5% | |

| 1934 | 9.8% | |

| 1935 | 10.8% | |

| 1936 | 11.1% | |

| 1937 | 18.6% | |

| 1938 | 23.9% | |

| 1939 | 24.8% | |

| 1940 | 23.5% | |

| 1941 | 25.4% | |

| 1942 | 24.2% | |

| 1943 | 30.1% | |

| 1944 | 32.5% | |

| 1945 | 33.4% | |

| 1946 | 31.9% | |

| 1947 | 31.1% | 52.0% |

| 1948 | 30.5% | 52.6% |

| 1949 | 29.6% | 52.7% |

| 1950 | 30.0% | 52.8% |

| 1951 | 32.4% | 53.4% |

| 1952 | 31.5% | 53.1% |

| 1953 | 33.2% | 54.4% |

| 1954 | 32.7% | 53.7% |

| 1955 | 32.9% | 53.8% |

| 1956 | 33.2% | 54.1% |

| 1957 | 32.0% | 54.6% |

| 1958 | 31.1% | 54.4% |

| 1959 | 31.6% | 54.0% |

| 1960 | 30.7% | 54.0% |

| 1961 | 28.7% | 53.2% |

| 1962 | 29.1% | 53.7% |

| 1963 | 28.5% | 53.8% |

| 1964 | 28.5% | 53.7% |

| 1965 | 28.6% | 53.9% |

| 1966 | 28.7% | 54.0% |

| 1967 | 28.6% | 53.2% |

| 1968 | 28.7% | 53.8% |

| 1969 | 28.3% | 53.8% |

| 1970 | 27.9% | 53.6% |

| 1971 | 27.4% | 53.4% |

| 1972 | 27.5% | 53.3% |

| 1973 | 27.1% | 53.4% |

| 1974 | 26.5% | 53.7% |

| 1975 | 25.7% | 53.8% |

| 1976 | 25.7% | 53.8% |

| 1977 | 25.2% | 53.6% |

| 1978 | 24.7% | 53.5% |

| 1979 | 25.4% | 53.2% |

| 1980 | 23.6% | 53.6% |

| 1981 | 22.3% | 53.5% |

| 1982 | 21.6% | 52.9% |

| 1983 | 21.4% | 52.9% |

| 1984 | 20.5% | 52.7% |

| 1985 | 19.0% | 52.2% |

| 1986 | 18.5% | 51.9% |

| 1987 | 17.9% | 51.5% |

| 1988 | 17.6% | 51.4% |

| 1989 | 17.2% | 50.8% |

| 1990 | 16.7% | 51.2% |

| 1991 | 16.2% | 51.4% |

| 1992 | 16.2% | 51.0% |

| 1993 | 16.2% | 48.9% |

| 1994 | 16.1% | 49.0% |

| 1995 | 15.3% | 49.1% |

| 1996 | 14.9% | 48.9% |

| 1997 | 14.7% | 48.6% |

| 1998 | 14.2% | 48.6% |

| 1999 | 13.9% | 48.5% |

| 2000 | 13.5% | 47.9% |

| 2001 | 13.5% | 48.0% |

| 2002 | 13.3% | 48.2% |

| 2003 | 12.9% | 48.3% |

| 2004 | 12.5% | 48.0% |

| 2005 | 12.5% | 47.8% |

| 2006 | 12.0% | 47.5% |

| 2007 | 12.1% | 48.6% |

| 2008 | 12.4% | 48.2% |

| 2009 | 12.3% | 47.9% |

| 2010 | 11.9% | 48.3% |

| 2011 | 11.8% | 47.4% |

| 2012 | 11.2% | 47.3% |

| 2013 | 11.2% | 47.4% |

Source: Data on union density follow the composite series found in Historical Statistics of the United States; updated to 2013 from unionstats.com. Data on the middle 60%'s share of income are from U.S. Census Bureau Historical Income Tables (Table F-2).

Conclusion

The erosion of collective bargaining has undercut wages and benefits not only for union members, but for nonunion workers as well. This has been a major cause of middle-class income stagnation and rising inequality. Yet, millions of workers desire union representation but are not able to obtain it. Restoring workers’ ability to organize and bargain collectively for improved compensation and a voice on the job is a major public policy priority.

Resources

1. Wage Stagnation in Nine Charts, by Lawrence Mishel, Elise Gould, and Josh Bivens, Economic Policy Institute, 2015

2. Unions, Inequality, and Faltering Middle-Class Wages, by Lawrence Mishel, Economic Policy Institute, 2012

3. Do Workers Still Want Unions? More Than Ever, by Richard B. Freeman, Economic Policy Institute, 2007

4. No Holds Barred: The Intensification of Employer Opposition to Organizing, by Kate Bronfenbrenner, Economic Policy Institute, 2009

5. Unions, Inequality, and Faltering Middle-Class Wages, by Lawrence Mishel, Economic Policy Institute, 2012

6. The Erosion of Collective Bargaining Has Widened the Gap Between Productivity and Pay, by David Cooper and Lawrence Mishel, Economic Policy Institute, 2015