EPI’s Daniel Costa appeared as a witness and submitted the following written testimony before the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary, on Wednesday, May 31, 2023 at 10:00 AM, for hearing titled “From Farm to Table: Immigrant Workers Get the Job Done.”

Introduction

Thank you to Senator Durbin, the Committee Chair as well as Ranking Member Graham, and the other distinguished members of the Committee for allowing me to testify at this hearing on the contributions of immigrant workers to the food supply chain and how to better protect them. I am a lawyer and researcher at the Economic Policy Institute, a nonprofit, nonpartisan think tank dedicated to advancing policies that ensure a more broadly shared prosperity, and that conducts research and analysis on the economic status of working America and proposes policies that protect and improve the economic conditions of low- and middle-income workers—regardless of their immigration status—and assesses policies with respect to how well they further those goals. I am also a Visiting Scholar at the Global Migration Center at the University of California, Davis, a university known for its focus on the study of agriculture. UC Davis is the top university in the nation for agricultural sciences, plant and animal sciences, and agricultural economics and policy research.

I am especially honored to be before the Judiciary Committee because I am myself the son of immigrants, each of whom came from a different country and through different immigration pathways, and who met each other in the great melting pot that is my home state of California. The first jobs that most family members on both my mother’s and father’s side had after arriving in the United States were in the food supply chain, in the agricultural heartland of California, the San Joaquin Valley, where I grew up, and now live. My parents and I are the direct beneficiaries of the American immigration system—but I also believe that the United States has benefitted greatly from immigration and the immigrants who arrive—both economically and culturally—which is why there is no question in my mind that immigration is good for the United States. It’s also why I believe that the United States should grow and expand pathways for immigrants, to allow them come and stay and integrate into the United States, and believe we should do much more to improve the migration pathways that currently exist, and we also should regularize immigrants who are in the United States who lack an immigration status or only have a precarious, temporary status, such as Temporary Protected Status, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, and parole.

The purpose of this hearing is to discuss the work that immigrant workers do across the entire food supply chain, from “farm to table,” and how immigration reforms could help immigrant workers and farms and business, as well as how best to protect both U.S. workers and immigrant workers. This hearing is especially timely given the countless stories of abuse and exploitation of immigrant workers who are employed in the low-wage jobs that support America’s food production and distribution. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the already-extreme vulnerabilities of this cohort of workers, who were considered by the federal government to be “essential” and who were required to work in person rather than remotely, and who suffered disproportionately in terms of covid infections and deaths. Despite the plight of workers across the food supply chain being broadcast across the front pages of newspapers and on television, policymakers did little to protect them and honor their contributions.

Employers and industry associations have now been complaining about labor shortages and the lack of a stable workforce and calling for immigration reforms that would provide them with additional workers, but virtually no action has been taken to improve conditions in a number of industries, including agriculture—to help attract and retain workers—nor have the necessary investments been made to improve labor standards enforcement to protect workers in those industries. Without those measures first, it is impossible to know if the claims made by employers are legitimate. In a number of industries, there is little evidence of shortages of workers—but ample evidence that there’s a shortage of decent wages and working conditions on offer—creating a false image of a shortage that employers then wish to resolve with temporary migrant workers who are indentured to them through nonimmigrant work visa programs. The fervor around so-called labor shortages has gotten so intense, in fact, that in response, numerous state legislatures around the country are now passing and proposing laws that peel back the few prohibitions that exist to protect against child labor, as some of my EPI colleagues have recently documented.1

In addition, many migrant workers who are already in the United States lack an immigration status or only have a precarious, temporary status, such as those with DACA and TPS, parole, or those who are asylum seekers, as well as those who are in a temporary nonimmigrant status with a work visa. The status of those workers is subject to change depending on conditions and the whims of policymakers; thus, the first needed step in terms of the immigration system is to stabilize the current workforce by ensuring migrant workers are regularized and have a quick path to permanent residence and citizenship. The employers and industries complaining that the U.S. workforce is not “stable” should look directly at Congress, which has the power to resolve and improve the status of immigrant workers.

Immigration, if done right, may be a perfectly reasonable response to labor shortages, but only when it aligns with broader strategies to lift workplace conditions. Our current workforce—whether migrants or U.S. workers—need and expect support in the form of regularization, access to green cards, and improved wages and working conditions and labor standards. Immigration is not the only policy response available to lawmakers—raising wages and investing in training are other examples of responses—but immigration is certainly an option, if done right.

All immigration pathways, including our refugee and asylum systems, can be vehicles for economic growth and workforce expansion, not just those that are employment-based by design. To the extent that pathways are increased with the primary intention of meeting employer need, those pathways must include, at a minimum, a credible method to determine whether the need is real if shortages exist (and not a system that simply relies on the attestations of employers). U.S. workers must have a fair opportunity to apply and be considered first for U.S. jobs for which they are qualified

When opportunities are offered to migrant workers, they must be fair. At a minimum, migrant workers must be paid fairly according to U.S. standards, have adequate protections against retaliation and access to justice when their rights are violated. As importantly, Congress must create a clear and direct path to permanent residence that the migrant worker controls (rather than one that is controlled by the employer). Unfortunately, when it comes to U.S. temporary work visa programs, the U.S. government is failing to meet these basic standards and provide these basic rights to U.S. workers and migrant workers alike.

Furthermore, two of the most well-known and important temporary work visa programs in the United States, the H-2A visa program—for temporary and seasonal jobs in agriculture—and the H-2B program—for temporary and seasonal jobs outside of agriculture, have been an integral part of the public discourse on migrant workers and the food supply chain. Employer groups and industry associations have been calling to expand and deregulate both programs. Shamefully, policymakers have supported budget riders allowing employers to hire more H-2A and H-2B workers, while also lowering wage standards and watering down other important worker protections.

While the size of both the H-2A and H-2B programs has increased rapidly in recent years—during that time, few, if any, new protections have been implemented to ensure that workers in those programs and industries are adequately protected. Congress and federal agencies have failed to implement needed measures to lift standards and safeguard fundamental rights, despite numerous and egregious cases of worker abuses and exploitation including wage theft, health and safety violations, discrimination, human trafficking, and even death.

My written testimony will discuss the importance of the immigrant workforce in the United States and the need to invest in improving labor standards enforcement to protect workers, with a close look at labor standards enforcement in agriculture, including a discussion of wages for farmworkers and the false narratives around the discussion about the Adverse Effect Wage Rate for H-2A farmworkers. It will then turn to a discussion of U.S. temporary work visa programs, providing a background on their usage and the flaws that are common across them, and offer common sense solutions for the programs in their entirety, along with a specific focus on the H-2A and H-2B visa programs.

Immigrant workers in the U.S. economy and the food supply chain

Numerous scholars, institutions, and government agencies have documented the key role that immigrant and nonimmigrant workers play in the U.S. economy, including in the U.S. food supply chain. Without immigrant workers, many sectors of the economy would cease to function adequately—whether it be the construction of buildings, crop production, or information technology services. This section discusses and cites some of those sources.

Immigrant workers play an important role in nearly all sectors of the economy

The latest report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) on the labor force characteristics of foreign-born workers shows that in 2022, immigrant workers accounted for 18.1% of the U.S. civilian labor force, an increase of 0.7% compared to 2021.2 According to the U.S. Census, the share of the U.S. population that is foreign-born was 13.6% in 2021; if this share held in 2022,

It means that immigrants are overrepresented in the labor force by 4.5 percentage points. The labor force participation rate of immigrants was 65.9%, which was 4.4 percentage points higher than the labor force participation rate of the native-born.3

According to BLS, immigrant workers were also “more likely than native-born workers to be employed in service occupations (21.6 percent versus 14.8 percent); natural resources, construction, and maintenance occupations (13.9 percent versus 7.9 percent); and production, transportation, and material moving occupations (15.2 percent versus 12.1 percent).”4 Other sources made similar findings. For example, the Migration Policy Institute (MPI) reported that immigrants accounted for 17% of the workforce between 2017 and 2021, and represented 21% of all workers in the food industry, excluding restaurants. They also reported that immigrants were 18% of transportation workers, 22% of grocery and farm product wholesalers, 35% of meat processing workers, 25% of seafood processing workers, and 16% of grocery retail workers.5

The Immigration Research Initiative also recently reported on the immigrant workforce. “Immigrants are a big and important part of the economy,” the report stresses, with immigrant labor responsible for 17 percent of total GDP in the United States.”6 Contrary to common misperception, the report shows, immigrants work in jobs across the economic spectrum, and in a wide range of occupations. The report underscores two basic realities. On the one hand, the majority of immigrants are in middle- or upper-wage jobs—with 48% employed in middle-wage jobs, earning more than 2/3 of median earnings for full-time workers (or $35,000 per year), and 17% are in upper-wage jobs, earning more than double the median. On the other hand,

immigrants are “at the same time disproportionately likely to be in low-wage jobs. In all, 35 percent of immigrants are in jobs paying under $35,000, compared to 26 percent of U.S.-born workers.”7 The immigrants employed in the food supply chain occupations and industries cited above by MPI, as well as those employed in agricultural jobs like crop farming and livestock production, are overwhelmingly likely to be part of the 35% of immigrants in low-wage jobs.

These data show that immigrant workers are playing a vital role all across the food supply chain and in countless other industries. This is virtually an undisputable claim.

Millions of immigrant workers lack an immigration status or have only a precarious, temporary status, including many in the food supply chain

While the importance of immigrants to the U.S. economy is generally understood, there is generally less discussion about the impact of the different statuses of immigrants in the mainstream public discourse, especially with respect to the varying labor market outcomes associated with those statuses. For employers who claim they lack a “stable” workforce, one of the key drivers is likely to be the lack of a stable and permanent status for too many immigrant workers.

The Pew Research Center has reported on the makeup of the U.S. immigrant population, by immigration status, showing that 45% of immigrants are naturalized citizens, 27% are lawful permanent residents (also known as green card holders), while 23% are unauthorized immigrants who lack status, and 5% of the total foreign-born population are temporarily residing in the United States with nonimmigrant visas.8 The latest estimate from the Center for Migration Studies shows that in 2019 there were 10.3 million total unauthorized immigrants residing in the United States, with 7.3 million of them of working age and participating in the U.S. labor force.9 The United States stands alone in terms of having such high share of its immigrants lacking an immigration status, and no country comes close in terms of an absolute number of unauthorized immigrants.

The 7.3 million unauthorized immigrant workers are not fully protected by U.S. labor laws because they lack an immigration status: Unauthorized workers are often afraid to complain about unpaid wages and substandard working conditions because employers can retaliate against them by taking actions that can lead to their deportation. That also makes it difficult for unauthorized immigrants to join unions and help organize workers. This imbalanced relationship gives employers extraordinary power to exploit and underpay these workers, ultimately making it more difficult for similarly situated U.S. workers to improve their wages and working conditions.

The exploitation described here is not theoretical. A landmark study and survey of 4,300 workers in three major cities found that 37.1% of unauthorized immigrant workers were victims of minimum wage violations, as compared with 15.6% of U.S.-born citizens. Further, an astounding 84.9% of unauthorized immigrants were not paid the overtime wages they worked for and were legally entitled to.10

There are also many migrant workers whose status is in a grey area: they may not have a permanent path to remain in the United States, but have some protection from deportation, along with an Employment Authorization Document (EAD) issued by United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), which permits them to work lawfully. Having an EAD reduces the reasonable fear that unauthorized immigrants have of employer retaliation that can lead to deportation. A few of the major categories of migrants with EADs include asylum applicants and those who were recently granted asylum, parolees, those who were granted Temporary Protected Status (TPS) or established prima facie eligibility for TPS, and those who qualified for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (better known as DACA). In fiscal year 2022, there were approximately 1.8 million migrant workers with valid EADs in those categories alone.11

When it comes to the 5% of migrants that Pew estimates are in the United States with temporary visas, I’ve calculated that of that total 5%, approximately 2.1 million are employed in the U.S. labor force in a number of different work visa programs.12 As will be discussed in-depth later in this testimony, the migrant workers in these programs are among the most exploited laborers in the U.S. workforce because the employment relationship created by the visa programs leaves workers powerless to defend and uphold their rights, due to fear of retaliation and deportation. Temporary migrant workers are usually tied to one employer and cannot change jobs if their boss is abusive or breaks the law, and the exorbitant fees charged to them by labor recruiters for employment opportunities in the United States leave workers indebted and indentured to both employers and recruiters.

Three of the main temporary work visa programs utilized by U.S. employers across the food supply chain, for almost exclusively low-wage jobs, are the H-2A, H-2B, and J-1 visa programs. The H-2A program, used almost exclusively by employers in the food supply chain, allows employers to hire workers from abroad for agricultural jobs that normally last less than one year, including picking crops and sheepherding. There is no numerical limit on H-2A visas, and in recent years, the H-2A program has grown sharply, to approximately 300,000 workers in 2022. The H-2B program allows employers to hire temporary workers in low-wage nonagricultural jobs like landscaping, forestry, food processing, hospitality, and construction. There is an annual numerical limit of 66,000, but workers often stay longer than one year or have their stay extended, and congressional appropriations riders have raised the cap in recent years, resulting in approximately 150,000 H-2B workers in 2022 (as discussed later in this testimony). According to the Office of Foreign Labor Certification, approximately 10.5% of H-2B jobs were certified for occupations in the food supply chain.13

The J-1 visa is part of the Exchange Visitor Program, a cultural exchange program run by the State Department that has more than a dozen different J-1 programs, including programs that permit Fulbright Scholars to come to the United States, but also five de facto low-wage work visa programs. J-1 workers are employed in a number of low-wage occupations like au pairs, camp counselors, maids and housekeepers, and lifeguards, but many—especially in the Summer Work Travel program, the largest J-1 program—are employed in the food supply chain, by staffing restaurants, as well as smaller food stores and concessions stands like ice cream shops, including at amusement parks and national parks.14 The Summer Work Travel Program has a numerical limit of 109,000 per year; and 92,619 temporary migrant workers were employed through it in 2022.

Together, there were close to 550,000 temporary migrant workers employed in just these three visa programs in 2022, rivaling the number of low-wage temporary migrant workers at the peak of the Bracero program,15—a program so notorious for worker abuses that Congress eventually shut it down—with the vast majority employed across the food supply chain. Like the Braceros before them, temporary migrant workers in the H-2A, H-2B, and J-1 programs—and most other work visa programs—are indentured to their employers and have limited workplace rights. The trend towards temporary work visa programs—instead of providing migrants with a permanent immigrant status—is a trend that is being observed across the OECD, and has been documented by migration scholars.16 It is a particularly troubling trend, considering the consensus that exists among economists that permanent residence and citizenship raises wages and reduces poverty.17

Immigration is the government’s top federal law enforcement priority while labor standards enforcement agencies are starved for funding and too understaffed to adequately protect workers

Since this hearing is focused on how of immigration and labor are deeply intertwined, it must be noted how Congress has heavily prioritized the enforcement of immigration laws—much to the detriment of labor and employment laws—as evidenced by the massive imbalance in appropriations made to enforce each. For too long, employers have lobbied members of Congress to keep funding levels unrealistically and disastrously low for agencies like the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) and the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB)—so low that they cannot adequately fulfill their missions. The result is an environment of near impunity for rampant violators of labor and wage and hour laws, a situation brought to light by the recent wave of labor organizing across the country as workers make it clear that they are unwilling to continue accepting unsafe and unjust conditions on the job.

“Budgets are moral documents,”18 and one clear way to understand the priorities of a government is to look at how it spends money. For at least the past decade, the U.S. Congress has placed little value on worker rights and working conditions. A recent comparative analysis I published of federal budget data from 2012 to 2021 reveals that the top federal law enforcement priority of the United States is to detain, deport, and prosecute migrants, and to keep them from entering the country without authorization. Protecting workers in the U.S. labor market—by ensuring that their workplaces are safe and that they get paid every cent they earn—is barely an afterthought.

This situation leaves migrant workers especially vulnerable to employer lawbreaking. There are not enough federal agents to police employers, while a massive immigration enforcement dragnet threatens workers with deportation. Employers take advantage of the climate of fear this creates to prevent workers from reporting workplace abuses. Workers who find the courage to speak up can be retaliated against in ways that can set the deportation process in motion.

The wide gap in government funding between immigration and labor standards enforcement has persisted for at least a decade

In 2013, the Migration Policy Institute made headlines with a report highlighting how appropriations for immigration enforcement agencies exceeded the combined funding for the five main U.S. federal law enforcement agencies by 24%.19 Updating these figures for its 2019 report, the institute revealed how in 2018, after another six years of skyrocketing spending, immigration enforcement agencies received $24 billion, or $25.6 billion in 2021 dollars after adjusting for inflation.20 This amount is “34 percent more than [what was] allocated for all other principal federal criminal law enforcement agencies combined” [italics in original], including the Federal Bureau of Investigation; the Drug Enforcement Administration; the Secret Service; the U.S. Marshals Service; and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives. Both reports bring to light the fact that immigration enforcement has undoubtedly become the U.S. government’s top federal law enforcement priority.

Not much has changed since 2018. My analysis of DHS budget documents reveals that Congress appropriated another $25 billion in fiscal year 2021 to enforce immigration laws, while Department of Justice and DHS budget documents show an appropriation of $20.4 billion to the principal federal criminal law enforcement agencies.21

But where do labor standards and worker rights fit in?

My analysis of federal budget data also reveals that government spending on immigration enforcement in 2021 was nearly 12 times the spending on labor standards enforcement—despite the mandate of the labor agencies to protect the 144 million workers employed at nearly 11 million workplaces.22 Labor standards enforcement agencies across the federal government received only $2.1 billion in 2021. (See Figure A.)

This is an important fact to acknowledge, because having a robust system for labor standards enforcement is a key strategy to balance the interests of employers—in having the labor force they need—and those of both immigrant and U.S. workers—in having decent wages and working conditions and recourse when employers break the law. Any new immigration reforms considered by Congress should include increased funding and strong mandates for labor standards enforcement.

Government funding for immigration enforcement was nearly 12 times as much as labor standards enforcement funding in 2021: U.S. government funds appropriated for immigration and labor standards enforcement, 2021

| Immigration enforcement | Labor standards enforcement | |

|---|---|---|

| 2021 | $25.0 | $2.1 |

Notes: Values are adjusted to constant 2021 dollars and reflect totals for the U.S. government’s fiscal year (October 1 to September 30).

Notes: Values are adjusted to constant 2021 dollars and reflect totals for the U.S. government’s fiscal year (October 1 to September 30). The immigration enforcement total for 2021 includes funding for U.S. Customs and Border Protection, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and the Office of Biometric Identity Management. Totals for labor standards enforcement include appropriations for all subagencies, administrations, and offices of the U.S. Department of Labor considered for “worker protection” in budget documents, including the Employee Benefits Security Administration, Office of Workers’ Compensation Programs, Wage and Hour Division, Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs, Office of Labor-Management Standards, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, Mine Safety and Health Administration, and the Office of the Solicitor, in addition to two other agencies not within the Department of Labor: the National Labor Relations Board and the National Mediation Board.

Sources: U.S. Department of Labor, Fiscal Year 2023—Department of Labor, Budget in Brief and Archived Budgets, fiscal years 2012–2022; National Mediation Board, Congressional Justifications, fiscal years 2014–2023; National Labor Relations Board, Performance Budget Justification, fiscal years 2012–2023; and U.S. Department of Homeland Security, DHS Budget, Congressional Budget Justification for Fiscal Years 2012–2023.

The appropriations story is largely the same over the past decade and across three presidential administrations. As Figure B shows, in 2012—a decade ago—Congress appropriated $21.4 billion for immigration enforcement but only $2.4 billion for labor standards enforcement (in constant 2021 dollars). In fact, 2012 was the peak year for labor standards enforcement funding for the 2012–2021 period. Shockingly, the budget for labor standards actually declined by $300 million from 2012 to 2021. Meanwhile, immigration enforcement funding peaked in 2019 at $26.9 billion. The average annual amount appropriated for immigration enforcement funding over the past decade was $23.4 billion, while the average for labor standards enforcement was $2.2 billion.

Over the past decade, average annual funding for immigration enforcement has been over 10 times as much as labor standards enforcement funding: U.S. government funds appropriated for immigration and labor standards enforcement, 2012–2021

| Immigration enforcement | Labor standards enforcement | |

|---|---|---|

| 2012 | $21.4 | $2.4 |

| 2013 | $20.2 | $2.2 |

| 2014 | $21.1 | $2.3 |

| 2015 | $21.7 | $2.3 |

| 2016 | $22.0 | $2.3 |

| 2017 | $23.4 | $2.2 |

| 2018 | $25.6 | $2.2 |

| 2019 | $26.9 | $2.1 |

| 2020 | $26.3 | $2.2 |

| 2021 | $25.0 | $2.1 |

Notes: Values are adjusted to constant 2021 dollars and reflect totals for the U.S. government’s fiscal year (October 1 to September 30).

Notes: Values are adjusted to constant 2021 dollars and reflect totals for the U.S. government’s fiscal year (October 1 to September 30). The immigration enforcement total for 2012 includes appropriations for U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and the U.S. Visitor and Immigrant Status Indicator Technology program. Immigration enforcement totals for 2013 to 2018 include appropriations for CBP and ICE. Immigration enforcement totals for 2019 to 2021 include appropriations for CBP, ICE, and the Office of Biometric Identity Management. Totals for labor standards enforcement include appropriations for all subagencies, administrations, and offices of the U.S. Department of Labor considered for “worker protection” in budget documents, including the Employee Benefits Security Administration, Office of Workers’ Compensation Programs, Wage and Hour Division, Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs, Office of Labor-Management Standards, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, Mine Safety and Health Administration, and the Office of the Solicitor, in addition to two other agencies not within the Department of Labor: the National Labor Relations Board and the National Mediation Board.

Sources: U.S. Department of Labor, Fiscal Year 2023—Department of Labor, Budget in Brief and Archived Budgets, fiscal years 2012–2022; National Mediation Board, Congressional Justifications, fiscal years 2014–2023; National Labor Relations Board, Performance Budget Justification, fiscal years 2012–2023; and U.S. Department of Homeland Security, DHS Budget, Congressional Budget Justification for Fiscal Years 2012–2023.

This estimate for labor standards enforcement appropriations uses an expansive definition that includes federal budget data for fiscal years 2012 to 2021 for the eight subagencies, administrations, and offices that DOL considers for “worker protection,” in addition to the NLRB and the National Mediation Board.

The wide staffing gap between immigration and labor standards enforcement agencies has persisted for at least a decade

Federal budget data show that labor enforcement agencies are staffed at only a fraction of the levels required to adequately fulfill their missions. In 2021, as Figure C shows, Congress gave the 10 labor standards enforcement agencies combined only enough funding to employ fewer than 9,400 personnel, while the immigration enforcement agencies—U.S. Customs and Border Protection (which includes the U.S. Border Patrol), U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and the Office of Biometric Identity Management—received enough funds to employ a total of almost 79,000 personnel, more than eight times as many personnel as the labor standards agencies.

In 2021, immigration enforcement agencies had eight times as many staff as labor standards agencies: Annual full-time equivalent staffing levels at immigration and labor standards enforcement agencies, 2012–2021

| Immigration enforcement | Labor standards enforcement | |

|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 81,127 | 12,288 |

| 2013 | 79,373 | 12,297 |

| 2014 | 80,228 | 11,918 |

| 2015 | 78,669 | 11,744 |

| 2016 | 78,585 | 11,465 |

| 2017 | 77,845 | 11,188 |

| 2018 | 78,645 | 10,419 |

| 2019 | 81,112 | 10,843 |

| 2020 | 83,689 | 9,669 |

| 2021 | 78,938 | 9,337 |

Notes: The number of full-time equivalent staff reflects totals for the U.S. government’s fiscal year (October 1 to September 30).

Notes: The number of full-time equivalent staff reflects totals for the U.S. government’s fiscal year (October 1 to September 30). The immigration enforcement staffing total for 2012 includes personnel at U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and the U.S. Visitor and Immigrant Status Indicator Technology program. Immigration enforcement staffing totals for 2013 to 2018 include staff at CBP and ICE. Immigration enforcement totals for 2019 to 2021 include staff at CBP, ICE, and the Office of Biometric Identity Management. Totals for labor standards enforcement include appropriations for all subagencies, administrations, and offices of the U.S. Department of Labor considers for “worker protection” in budget documents, including the Employee Benefits Security Administration, Office of Workers’ Compensation Programs, Wage and Hour Division, Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs, Office of Labor-Management Standards, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, Mine Safety and Health Administration, and the Office of the Solicitor, in addition to two other agencies not within the Department of Labor: the National Labor Relations Board and the National Mediation Board.

Sources: U.S. Department of Labor, Fiscal Year 2023—Department of Labor, Budget in Brief and Archived Budgets, fiscal years 2012–2022; National Mediation Board, Congressional Justifications, fiscal years 2014–2023; National Labor Relations Board, Performance Budget Justification, fiscal years 2012–2023; and U.S. Department of Homeland Security, DHS Budget, Congressional Budget Justification for Fiscal Years 2012–2023.

Figure C also shows the staffing levels for immigration and labor standards enforcement over the past decade, 2012 to 2021. Labor standards enforcement agencies’ staffing levels peaked in 2012 at 12,288. Alarmingly, staffing at those agencies declined by nearly a quarter over the decade, hitting a low of just 9,337 in 2021.

Immigration enforcement staffing for the 2012–2021 period peaked in 2020 at 83,689. Average staff levels over the 10-year period were 79,821 for immigration enforcement and 11,117 for labor standards enforcement; in other words, immigration enforcement agency staff numbers are, on average, 618% greater than those of labor standards enforcement agencies (seven times as many personnel).

The wide funding gap between immigration and labor standards enforcement hurts all workers—including migrant workers

So why does any of this matter? Because it is increasingly more difficult to ensure that all workers—whether they were born in the United States or abroad—are treated fairly in the workplace. Budgets for labor standards enforcement agencies are shrinking, as shown above. Employer tactics such as forced arbitration prevent workers from suing in court when they are robbed by their employers.23 And a growing body of research shows that workers attempting to change jobs face many challenges.24 Making matters worse, without a strong mandate and funding from Congress to enforce labor standards, the executive branch can severely limit the work that labor agencies do on behalf of workers through executive actions, regulatory policy, and even political appointees—something the former Trump administration specialized in.25

Vastly underfunded labor agencies combined with enforcement-only immigration policies hypercharged by runaway budgets risk enabling retaliation against immigrant workers who stand up for their rights on the job. When immigrant workers can’t stand up for their rights, it degrades labor standards for their American counterparts working alongside them.26 Perhaps that is why employers rob their immigrant employees at much higher rates than those who are U.S. citizens.27

All workers face too much risk if they act to make their workplaces safer and fairer. But for nearly 8 million workers—roughly 5% of the U.S. labor force28—those risks include deportation and family separation because they lack immigration status.

Temporary migrant workers represent another significant and rapidly growing segment of the workforce. These are migrant workers employed through temporary visas (known as “nonimmigrant” visas under U.S. law).29 There are roughly 2 million temporary migrant workers employed in the United States, accounting for 1.2% of the total labor force.30 These workers have good reason to fear retaliation and deportation if they speak up about wage theft, workplace abuse, or working conditions such as substandard health and safety procedures on the job—not because they lack valid immigration status but because their visas are almost always tied to a single employer who controls both their livelihoods and their visa status.

No worker should ever have to risk deportation in order to file a claim with a labor agency, but that’s the reality for 6% of the entire U.S. workforce in a grossly imbalanced enforcement context.

Effective labor standards enforcement in agriculture is necessary to protect farmworkers

Now that I have contextualized the state of labor standards enforcement in the United States vis-à-vis immigration enforcement, I turn to a discussion of labor standards enforcement in agriculture.

Farmworkers in the United States: A background on numbers and the existing legal framework

Farmworkers support the first and most important element of the food supply chain, by growing and picking crops and tending to livestock. Yet farmworkers in the United States earn some of the lowest wages in the labor market and experience an above-average rate of workplace injuries.31 In addition, a large share of them are also vulnerable to exploitation and abuse in the workplace because of their immigration status.

No one knows the exact number of workers employed for wages on U.S. farms during the year, although there are multiple estimates. The Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) shows that average annual employment of farmworkers who are employed on farms that report to state unemployment insurance (UI) agencies was 1.2 million in 2021,32 but estimated that there were an additional 300,000 “wage and salary” farmworkers not included in QCEW data,33 suggesting average employment of 1.5 million in 2019.

The QCEW reports average employment, which underestimates the number of unique farmworkers due to seasonality and turnover. The Census of Agriculture (COA) asks farmers (i.e. farm employers or farm owners) how many workers they employ directly; in 2017, farmers reported hiring 2.4 million farmworkers.34 However, the COA does not report workers who are brought to farms by nonfarm employers such as nonfarm labor contractors, and double counts workers employed by two farms, so 2.4 million is not a count of unique farm workers. The Current Population Survey included a December supplement through the 1980s, and it reported about 2.5 million farmworkers when annual average employment ranged between about 1.1 million to 1.3 million, suggesting about two unique workers per year-round equivalent job, or 2.5 million to 3.4 million workers today based on QCEW data.35

The U.S. Department of Labor’s National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS) reports the characteristics of crop farmworkers, excluding those who are migrants employed through the H-2A temporary work visa program for agriculture, but not their number. The NAWS reports that 44% of the non-H-2A crop workers were unauthorized immigrants in 2019–2020,36 and as discussed above there were roughly 300,000 H-2A workers employed in the United States in 2022, who worked for an average of six months out of the year, representing roughly 10% to 15% of farmworkers employed on U.S. crop farms. Both unauthorized and H-2A workers have limited labor rights and are vulnerable to wage theft and other abuses due to their immigration status.37 The remaining farm workforce, roughly just under half of all farmworkers, are U.S. citizens and legal immigrants with full rights and agency in the labor market. But that means that roughly half of all farmworkers are vulnerable to violations of their rights because of their lack of an immigration status or their precarious, temporary immigration status.

The U.S. Department of Labor’s (DOL) Wage and Hour Division (WHD) is the federal agency that protects the rights of farmworkers in terms of wage and hour laws, including those that protect H-2A workers. WHD labor standards enforcement actions are intended to ensure that the rights of workers are protected, and to level the playing field for employers, so that employers that underpay workers or engage in other cost-reducing behavior in violation of wage and hour laws do not gain a competitive advantage over law-abiding employers. WHD aims to “promote and achieve compliance with labor standards to protect and enhance the welfare of the nation’s workforce” by enforcing 13 federal labor standards laws, including the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), which requires minimum wages and overtime pay, and regulates the employment of workers who are younger than 18, as well as the Family and Medical Leave Act, and laws governing government contracts, consumer credit, and the use of polygraph testing, etc.38 WHD also enforces two laws and their implementing regulations specific to agricultural employment. One is the Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act (MSPA), the major federal law that protects U.S. farmworkers. The other is the statute that establishes the H-2A program.

However, federal law exempts farmworkers from some of the basic protections that cover most other workers in the U.S. labor market. The National Labor Relations Act—the federal law that provides the right to form and join unions, and to engage in protected, concerted activities to improve workplace conditions, does not protect farmworkers. Only California and New York have enacted state legislation to allow farmworkers to have the rights covered by the federal NLRA. Farmworkers are partially covered by the FLSA, but not the FLSA’s overtime provisions that require most workers to be paid time and a half after working eight hours in a day or 40 hours in a week. Some states, including California and New York, have enacted laws that are gradually phasing-in the overtime threshold for farmworkers until it eventually reaches 8 hours per day and/or 40 hours per week, while a small number of states have enacted or are phasing-in overtime thresholds for farmworkers that require a higher number of hours worked per week before farmworkers get overtime pay, with some of the laws nevertheless still exempting many farmworkers from overtime pay.39

Data on labor standards enforcement on farms reveal the biggest violators and raise new questions about how to improve and target efforts to protect farmworkers

In December 2020, Dr. Philip Martin, Dr. Zach Rutledge, and I published a lengthy report analyzing 20-years of data from WHD on their enforcement actions in agriculture,40 and Martin and I analyzed more recent data for a forthcoming EPI report that will be published later this year. The rest of this section highlights some of the key findings from those two reports.

The number of federal and wage and hour inspections continued to decline and hit a record low in 2022 under the Biden administration

This section analyzes WHD’s aggregate enforcement data. WHD conducted over 34,000 investigations in U.S. agriculture between fiscal years 2000 and 2022, an average of almost 1,500 per year (1,485). The WHD data we use represent investigations that were closed by year (meaning they have been concluded or resolved), which means that some cases may have begun in earlier fiscal years, and some that began in the current fiscal year are not included because they have not yet been closed.

Figure D shows a clear downward trend in the number of closed WHD investigations of agricultural employers over the past two decades, from more than 2,000 a year in the early 2000s to 1,000 or fewer a year during the last two fiscal years, i.e., during the Biden administration. In 2022, WHD conducted only 879 investigations of agricultural employers, an average of 73 a month, and just over a third of the 2,431 agricultural investigations conducted in 2000, the peak year for WHD agricultural investigations.

The number of federal wage and hour investigations of farms hit record low in 2022: Wage and Hour Division investigations of agricultural employers, fiscal years 2000–2022

| Fiscal Year | Inspections of agricultural employers |

|---|---|

| 2000 | 2,431 |

| 2001 | 2,300 |

| 2002 | 2,176 |

| 2003 | 1,495 |

| 2004 | 1,630 |

| 2005 | 1,449 |

| 2006 | 1,410 |

| 2007 | 1,666 |

| 2008 | 1,600 |

| 2009 | 1,377 |

| 2010 | 1,277 |

| 2011 | 1,527 |

| 2012 | 1,659 |

| 2013 | 1,673 |

| 2014 | 1,430 |

| 2015 | 1,361 |

| 2016 | 1,275 |

| 2017 | 1,307 |

| 2018 | 1,076 |

| 2019 | 1,125 |

| 2020 | 1,036 |

| 2021 | 1,000 |

| 2022 | 879 |

Source: Authors’ analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, Agriculture data table.

Few investigations mean that most farms are never investigated by WHD

The Census of Agriculture (COA) reported over 513,000 U.S. farms with labor expenses for directly hired workers in 2017,41 and 112,134 agricultural establishments were registered with state unemployment insurance agencies in the third quarter of 2022, according to the QCEW.42

At 879 WHD investigations of agricultural employers in 2022, and using the QCEW number of establishments in 2022 as a reference for the number of agricultural employers—which includes only farms registered in the unemployment insurance system—the probability that a farm will be investigated for violating federal wage and hour laws in a given year is less than one percent: 0.7%.43

Despite the low number of investigations, it is also true that when WHD investigators inspect an agricultural employer, they nearly always detect violations of wage and hour laws. As we reported in 2020 and will discuss below, WHD detects violations 70% of the time they conduct an investigation—a sign that many agricultural employers are violating the law. Among the 70% of investigations that detected violations between 2005 and 2019, almost 40% found one to four violations on the farm and 31% found five or more.44

DOL’s Wage and Hour Division is underfunded and understaffed

Why are there so few investigations of agricultural employers? A major reason is too little funding and staffing, a topic we have addressed before.45 The Wage and Hour Division is responsible for enforcing provisions of several federal laws related to minimum wage, overtime pay, child labor, federal contract workers, work visa programs, migrant and seasonal agricultural workers, family and medical leave, and more. Yet, despite this broad portfolio and the 165 million workers who are covered by these protections,46 funding for WHD has not kept pace with the growth of the U.S. labor force.

Figure E shows that, in inflation-adjusted 2022 dollars, WHD’s budget in 2006 was $241 million, and in 2022, $246 million, an increase of just $5 million over nearly two decades. Lack of funding for WHD reflects the general decline in overall labor standards enforcement spending across the federal government from $2.4 billion in 2012 to $2.1 billion in 2021 (in 2021 dollars).47

In 2022, funding for the Wage and Hour Division was roughly the same as in 2006: Funding for the Wage and Hour Division in the U.S. Department of Labor, fiscal years 2006–2022

| Fiscal Years | Annual funding for the Wage and Hour Division |

|---|---|

| 2006 | $241,049,000 |

| 2007 | $245,012,000 |

| 2008 | $239,318,000 |

| 2009 | $263,988,000 |

| 2010 | $306,124,000 |

| 2011 | $296,769,000 |

| 2012 | $289,918,000 |

| 2013 | $270,742,000 |

| 2014 | $277,550,000 |

| 2015 | $280,988,000 |

| 2016 | $277,410,000 |

| 2017 | $271,569,000 |

| 2018 | $265,107,000 |

| 2019 | $262,106,000 |

| 2020 | $273,570,000 |

| 2021 | $265,686,000 |

| 2022 | $246,000,000 |

Note: Dollar amounts reported have been adjusted for inflation to constant 2022 dollars using the CPI-U-RS. As a result, the dollar amounts presented here may differ from the amounts reported in the source data.

Source: Department of Labor, Budget, Performance, and Planning reports, fiscal years 2008-2022, available at https://www.dol.gov/general/budget, accessed February 27, 2023.

Yet, in addition to the lack of funding and the more than 165 million workers WHD has a mandate to protect, the number of WHD investigators that the agency employs, who are primarily responsible for ensuring that federal wage and hour laws are actually followed on the ground across all 50 states and U.S. territories, is near an all-time low.

Figure F shows that there were only 810 WHD investigators at the end of November 2022 to enforce all federal wage and hour laws, two fewer than in 1973, the first year for which data are available, and 422 fewer than the peak year of 1978, when there were 1,232 WHD investigators. Meanwhile, the number of workers that WHD has a mandate to protect has increased sharply. The average number of WHD-covered workers in 2022 was 164.3 million, which amounts to 202,824workers for every wage and hour investigator. Compare this to 1973, when there were 72,588 covered workers for every wage and hour investigator.48 Investigators are now responsible for almost triple the number of workers than in 1973 (2.8 times more).

Number of federal wage and hour investigators is near its historic low: Number of Wage and Hour Division investigators, U.S. Department of Labor, 1973–2022

| Year | Investigators on board at year’s end |

|---|---|

| 1973 | 812 |

| 1974 | 869 |

| 1975 | 921 |

| 1976 | 964 |

| 1977 | 980 |

| 1978 | 1,232 |

| 1979 | 1,087 |

| 1980 | 1,059 |

| 1981 | 953 |

| 1982 | 914 |

| 1983 | 928 |

| 1984 | 916 |

| 1985 | 950 |

| 1986 | 908 |

| 1987 | 951 |

| 1988 | 952 |

| 1989 | 970 |

| 1990 | 938 |

| 1991 | 865 |

| 1992 | 835 |

| 1993 | 804 |

| 1994 | 800 |

| 1995 | 809 |

| 1996 | 781 |

| 1997 | 942 |

| 1998 | 942 |

| 1999 | 938 |

| 2000 | 949 |

| 2001 | 945 |

| 2002 | 898 |

| 2003 | 850 |

| 2004 | 788 |

| 2005 | 773 |

| 2006 | 751 |

| 2007 | 732 |

| 2008 | 731 |

| 2009 | 894 |

| 2010 | 1,035 |

| 2011 | 1,024 |

| 2012 | 1,067 |

| 2013 | 1,040 |

| 2014 | 976 |

| 2015 | 995 |

| 2016 | 974 |

| 2017 | 912 |

| 2018 | 835 |

| 2019 | 780 |

| 2020 | 823 |

| 2021 | 782 |

| 2022 | 810 |

Note: Numbers represent Wage and Hour Division investigators on staff at the end of each fiscal year (the federal government's fiscal year runs from October 1 to September 30), except for 2022, which represents the number of investigators on staff at the end of November 2022.

Sources: Author’s analysis of Wage and Hour Division (WHD) data on number of investigators from unpublished Excel files provided by WHD staff members to the author. Source for 2020 and 2021 is Rebecca Rainey, “Wage-Hour Investigator Hiring Plans Signal DOL Enforcement Drive,” Bloomberg Law, January 28, 2022. Source for 2022 is Rebecca Rainey, "Wage Division Enforcement Declines Again in Wake of Hiring Woes," Bloomberg Law, Decemer 28, 2022.

Another issue related to the funding and staffing challenges, has reportedly been WHD’s “issues with recruiting and retaining employees.” Bloomberg Law reported in December 2022 that WHD has “struggled to recruit new investigative staff” and WHD’s overall back wages recovered, employees who received back wages, and total number of hours spent on investigations “all dropped in fiscal year 2022 compared to the year prior” according to WHD data.49 Despite WHD’s stated intention to hire 100 new investigators in the Biden administration, a heavy workload and inadequate funding from Congress appears to be hindering WHD from hiring enough staff for the tasks at hand.

Despite few investigations, the amount of back wages and civil money penalties assessed by WHD are on a generally upward trend

Nonetheless, Figure G shows that despite fewer investigations and WHD investigators, the total back wages owed for all violations of federal wage and hour laws in agriculture has been on a generally upward trend. Figure G shows the back wages owed and civil money penalties assessed in agriculture between 2000 and 2022. (Back wages are the amount that WHD assesses is due to be paid to the workers by their employers as the result of an investigation. Civil money penalties, or CMPs, are additional monetary fines levied by WHD to punish and deter employers from violating wage and hour laws.) Both back wages and CMPs have been on a generally upward trend over the 23-year period, although there was a significant dip in back wages in 2022. Back wages peaked at $9.7 million in 2013 during the Obama administration, the same year that civil money penalty assessments peaked at $9.2 million. (All amounts are adjusted to constant 2022 dollars.)

Back wages owed and civil money penalties assessed in agriculture have been on a generally upward trend since 2000: Back wages and civil money penalties assessed (in millions of dollars) against agricultural employers by the Wage and Hour Division, fiscal years 2000–2022

| Fiscal year | Back wages | Civil money penalties |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | $2.27 | $2.34 |

| 2001 | 2.86 | 2.09 |

| 2002 | 3.31 | 1.93 |

| 2003 | 3.89 | 1.81 |

| 2004 | 1.89 | 2.57 |

| 2005 | 2.00 | 1.60 |

| 2006 | 2.46 | 1.18 |

| 2007 | 4.51 | 2.04 |

| 2008 | 2.88 | 1.84 |

| 2009 | 1.92 | 1.72 |

| 2010 | 4.24 | 1.48 |

| 2011 | 3.72 | 2.53 |

| 2012 | 6.73 | 5.84 |

| 2013 | 9.67 | 9.18 |

| 2014 | 5.57 | 3.83 |

| 2015 | 5.33 | 6.25 |

| 2016 | 5.91 | 4.31 |

| 2017 | 6.03 | 5.18 |

| 2018 | 4.90 | 7.63 |

| 2019 | 6.94 | 7.24 |

| 2020 | 8.11 | 7.25 |

| 2021 | 9.12 | 7.89 |

| 2022 | 5.82 | 7.98 |

Note: Dollar amounts reported have been adjusted for inflation to constant 2022 dollars using the CPI-U-RS. As a result, the dollar amounts presented here may differ from the amounts reported in the source data.

Source: Authors’ analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, Agriculture data table (last accessed February 26, 2023).

When WHD investigates, 70% of the time they detect employer violations

In addition, despite fewer investigations, it is the case that when WHD initiates an investigation of an agricultural employer, they often find violations. Figure H groups the number of violations found per investigation during the FY2005–FY2019 period, from zero to more than five violations per investigation. When looked at this way, the data reveal a U-shape among the violators, with almost 30% of investigations bunched at the zero and 31% bunched at more than five violations; those two ends of the spectrum account for almost two-thirds of the violations, while 17% of investigations found one violation and 23%, nearly a quarter, found two to four violations. However, overall, the data show that 70% of all investigations detected violations, while 30% detected zero violations. In addition, it should be noted that this figure does not account for the severity of the violations or the amounts assessed. In other words, some investigations that detected one or two violations may have detected egregious violations and found employers owing large amounts of back pay, while investigations that detected with five or more violations may have resulted in smaller amounts of back wages owed.

Over 70% of federal investigations of agricultural employers detected wage and hour violations: Violations detected during investigations of agricultural employers, by number of violations found per investigation, fiscal years 2005–2019

| Number of violations | Share of investigations |

|---|---|

| 0 violations | 29.5% |

| 1 violation | 16.7% |

| 2–4 violations | 22.7% |

| 5+ violations | 31.1% |

Note: Data include H-2A, MSPA, FLSA, and all other types of employment law violations in the agricultural sector.

Source: Authors' analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Compliance Action Data (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f).

Farm labor contractors are the worst violators of wage and hour laws in agriculture

One particular area of interest to highlight with respect to wage and hour enforcement in agriculture is the employment of farmworkers by farm labor contractors (FLCs). FLCs are nonfarm employers that act as staffing firms for farm employers. For FLCs, which correspond to NAICS code 115115, average employment was 181,000 in 2019, according to the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages from DOL; FLCs are a subset of the Support Activities for Crop Production category (NAICS 1151), which had average employment of 342,000 in 2019, meaning that FLCs accounted for 53% of U.S. crop support services employment.

FLCs accounted for 14% of total average employment in UI-covered agriculture of 1.3 million in 2019—including employment in both crops and animal agriculture—but accounted for one-quarter of all wage and hour law violations detected in agriculture (24%). Thus, the share of agricultural employment law violations committed by farm labor contractors was 10 percentage points greater than the FLC share of average annual agricultural employment. In practical terms, that means that farmworkers employed by FLCs or on farms that use FLCs are more likely to suffer wage and hour violations than farmworkers who are employed by farms directly.

We also found that 75% of all WHD investigations of FLCs detected violations, while 25% of investigations detected zero violations. We grouped the number of violations detected per investigation of FLCs, as shown in Figure I. The share of investigations of FLCs that found zero violations, at 25%, was significantly less than the share of investigations of FLCs that found five or more violations, 36%. Nearly two-fifths of investigations detected either one violation or two to four violations.

Three-fourths of federal investigations of farm labor contractors detected wage and hour violations: Violations detected during investigations of farm labor contractors, by number of violations found per investigation, fiscal years 2005–2019

| Number of violations | Share of investigations |

|---|---|

| 0 Violations | 25.3% |

| 1 Violation | 15.9% |

| 2–4 Violations | 22.9% |

| 5+ Violations | 35.9% |

Source: Authors' analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Compliance Action Data (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f).

We also reviewed violations by FLCs in the two major agricultural states of California and Florida. California and Florida each accounted for 14% of the total wage and hour violations detected as the result of WHD investigations nationwide, by far the most, followed by North Carolina with 10%, Texas and Washington with 5% each, and Oregon with 4%. These six states accounted for 52% of all wage and hour law violations found in agriculture. In the two states with the highest shares of violations, California and Florida, FLCs accounted for the largest share of the violations detected by WHD investigators. Figure J shows that FLCs accounted for 48% of the total violations in California during fiscal years 2005 to 2019, and Figure K shows that FLCs accounted for 50% of the total violations detected in Florida over the same period. This finding is particularly significant for California, given that FLCs now account for a majority of crop employment in the state.50

Employer violations detected in California by the Wage and Hour Division among all agricultural employers and farm labor contractors, fiscal years 2005–2019

| Year | Violations by all agricultural employers | Violations by farm labor contractors |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 1,233 | 972 |

| 2006 | 4,166 | 918 |

| 2007 | 1,931 | 1,189 |

| 2008 | 2,911 | 1,469 |

| 2009 | 2,202 | 1,645 |

| 2010 | 1,577 | 363 |

| 2011 | 2,909 | 1,949 |

| 2012 | 4,589 | 1,556 |

| 2013 | 5,420 | 3,348 |

| 2014 | 3,079 | 1,302 |

| 2015 | 2,181 | 947 |

| 2016 | 2,113 | 1,490 |

| 2017 | 1,902 | 570 |

| 2018 | 2,794 | 733 |

| 2019 | 315 | 240 |

Note: Violations by California farm labor contractor are a subset of employment law violations detected among all agricultural employers in California.

Source: Authors' analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Compliance Action Data (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f).

Employer violations detected in Florida by the Wage and Hour Division among all agricultural employers and farm labor contractors, fiscal years 2005–2019

| Year | Violations by all agricultural employers | Violations by farm labor contractors |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 1,225 | 670 |

| 2006 | 1,484 | 686 |

| 2007 | 4,469 | 1,643 |

| 2008 | 1,989 | 1,021 |

| 2009 | 2,034 | 1,020 |

| 2010 | 2,886 | 545 |

| 2011 | 4,045 | 1,726 |

| 2012 | 4,633 | 2,765 |

| 2013 | 2,380 | 1,084 |

| 2014 | 3,744 | 1,986 |

| 2015 | 3,338 | 2,360 |

| 2016 | 1,871 | 1,182 |

| 2017 | 1,837 | 974 |

| 2018 | 1,412 | 1,112 |

| 2019 | 989 | 455 |

Note: Violations by Florida farm labor contractor are a subset of employment law violations detected among all agricultural employers in Florida..

Source: Authors' analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Compliance Action Data (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f).

Violations in the H-2A visa program account for a growing share of back wages owed and civil money penalties assessed in agriculture—rising to nearly three-fourths during the Biden administration

WHD’s aggregate data on enforcement in agriculture list separately the violations detected when enforcing the three major federal employment laws and regulations covering farmworkers: (1) those that govern the H-2A visa program, (2) the Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act (commonly referred to as MSPA), the major federal law that protects U.S. farmworkers, and (3) the Federal Labor Standards Act (FLSA) along with all other wage and hour laws that WHD enforces.51 FLSA is the law that requires minimum wages and overtime pay and regulates the employment of workers who are younger than 18.

In order to have a better sense of which laws are being violated, we summed the back wages owed and the CMPs assessed for the 23-year period for which data are available (fiscal years 2000-22), for violations of H-2A, MSPA, and FLSA et al. (FLSA plus all other violations).52 We divided the sum of back wages and CMPs under each law by the sum of total back wages and CMPs assessed by WHD for the entire 23-year period, which gave us the relevant shares of back wages and CMPs that correspond to each law. (Note that employers often violate several wage and hour laws at once; WHD categorizes cases by the three major laws and they may overlap, but the sum of the three major categories corresponds closely with the total back wages and CMPs assessed by WHD.)

We found that violations of H-2A rules account for much higher shares of back wages owed and CMPs assessed than violations of other laws, and now account for an overwhelming share of the back wages owed and CMPs assessed.

Table 1 shows the shares of total back wages owed and CMPs assessed (combined) by type of legal violation for the 2000-22 period. H-2A violations accounted for nearly half (46%) of all back wages owed to farmworkers and CMPs assessed over the 23-year period, and their share rose sharply during the two years of the Biden administration. As Table 3 shows, WHD investigations during the Trump administration found that H-2A violations accounted for roughly half of the back wages and CMPs owed by farm employers during 2017-20, but the H-2A share rose to 73%, almost three-fourths, during the Biden administration. As a result, WHD investigations that find H-2A violations now account for the vast majority of back wages owed and CMPs assessed.

Violations of the H-2A visa program account for most of the back wages owed and civil money penalties assessed in agriculture: Share of total back wages owed and civil money penalties assessed by the Wage and Hour Division against agricultural employers, by type of legal violation, fiscal years 2000–2022

| Fiscal Year | H-2A | MSPA | FLSA et al. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 8% | 36% | 54% |

| 2001 | 24% | 37% | 36% |

| 2002 | 12% | 36% | 49% |

| 2003 | 19% | 24% | 55% |

| 2004 | 11% | 42% | 41% |

| 2005 | 27% | 29% | 42% |

| 2006 | 11% | 31% | 56% |

| 2007 | 11% | 29% | 58% |

| 2008 | 31% | 31% | 37% |

| 2009 | 27% | 42% | 30% |

| 2010 | 17% | 23% | 59% |

| 2011 | 33% | 27% | 37% |

| 2012 | 52% | 18% | 30% |

| 2013 | 70% | 10% | 20% |

| 2014 | 41% | 22% | 36% |

| 2015 | 59% | 16% | 25% |

| 2016 | 44% | 20% | 36% |

| 2017 | 49% | 20% | 30% |

| 2018 | 47% | 31% | 22% |

| 2019 | 42% | 34% | 23% |

| 2020 | 52% | 17% | 30% |

| 2021 | 73% | 10% | 17% |

| 2022 | 73% | 11% | 16% |

| TOTALS | 46% | 22% | 31% |

Note: Values represent the share of total back wages and civil money penalties assessed by the Wage and Hour Division (WHD) in the U.S. Department of Labor in a given fiscal year, according to the three broad categories of laws listed by WHD. "H-2A" represents violations of the laws and regulations governing the H-2A visa program; "MSPA" represents the Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act (commonly referred to as MSPA), which is the major federal law that protects U.S. farmworkers, and "FLSA et al." represents the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), which WHD data group with all other wage and hour laws that WHD enforces. FLSA is the U.S.’ main worker protection law that requires minimum wages and overtime pay and regulates the employment of workers younger than 18.

Source: Authors’ analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, Agriculture data table (last accessed February 26, 2023).

Recommendations to improve farm employer compliance with wage and hour laws and better protect farmworkers

Based on my research and the evidence presented in this testimony, it is clear that the first step to improve employer compliance with wage and hour laws on farms should be to hire more investigators to detect more violations—which will require Congress to appropriate more funding to WHD. Outgoing Labor Secretary Marty Walsh recently expressed a similar sentiment to the Washington Post, noting that he hoped Congress would provide “more money for enforcement officers…[because] you can’t handle the number of complaints if you don’t have the number of officers.”53 For fiscal year 2024, WHD has requested $81 million in additional funds compared to their 2023 funding level, which would result in an increase of 398 full-time staff across the agency (not just WHD investigators).54

Absent more funding from Congress, WHD will need to better target currently available resources, issue larger fines and more significant sanctions, and more frequently utilize existing legal mechanisms to encourage compliance, such as using the joint employment standard under the Fair Labor Standards Act and the Migrant and Seasonal Worker Protection Act, to hold farms accountable for FLC violations.55 If farm operators are jointly liable for violations committed by the FLCs that bring workers to their farms, they will have incentives to police their FLCs to ensure FLCs comply with the law. The concept of joint employment is longstanding, but DOL could use it more often and strengthen H-2A regulations to make clear that farm employers will be held jointly responsible for the actions of their FLCs.

In addition, when serious violations of FLSA are found, WHD can file a lawsuit asking a federal court for an injunction that seeks to prohibit the shipment and distribution of goods produced in violation of FLSA’s minimum wage, overtime, or child labor requirements, with what’s known as the “hot goods” provision.56 This supply-chain approach can be very effective because it sends a message to all businesses that they must not facilitate or acquiesce in wage and hour violations, and was used by former WHD administrator David Weil.57

Third, Congress and the Administration must recognize that the farm workforce of 2.4 million is becoming more vulnerable and in need of additional protection58—which requires both legislative and administrative action. About 70% of U.S. farmworkers were born in Mexico,59 and they include two very vulnerable groups, the unauthorized immigrants who arrived in their 20s and 30s in the 1990s—and are now in their 50s and may lack the language and skills to find nonfarm jobs—and temporary migrant H-2A workers who are tied to their employers by contracts, which means that they lose their right to remain in the United States if they lose their jobs. Most of the 5% of farmworkers from Central America are likely to be in a similar situation and facing similar challenges.60 Children and indigenous workers who hail from Latin America are also laboring in the fields and need protection.

A path to citizenship for unauthorized farmworkers, which would require legislation from Congress—or work authorization through deferred action or parole, which could be accomplished through the executive branch—could reduce the vulnerability of unauthorized farmworkers by allowing them to exercise their workplace rights. Options to increase the mobility of H-2A workers, such as regulations allowing them to more easily change employers, could be explored. The recent announcement by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) that clarifies the process for how migrant workers in labor disputes can access immigration protections can bolster worker protections from retaliation.61 WHD and other agencies within the Labor Department should issue more letters and statements of interest in support of deferred action for farmworkers and coordinate with DHS to facilitate quick adjudications that reflect the unique pressures faced by unauthorized and H-2A farmworkers.

And fourth, absent additional funding and resources to conduct more investigations, WHD should strategically target for enforcement the employers most likely to violate wage and hour laws, including the farm labor contractors who account for the largest share of violations,62 and employers who hire farmworkers through the H-2A visa program. Among the farms found to have committed wage and hour violations, as we showed in our 2020 report, repeat violators account for a significant share of the violations found in particular commodities and regions, which suggests the need to develop enforcement strategies that identify and monitor farm employers whose business models seem to be based on violating the law.63

Creating a front-end screening process to prohibit employers from hiring through H-2A if they have a track record of violating wage and hour and labor laws, for instance, could make a significant impact and lessen the burden on WHD’s investigators.64 And requiring program violators to submit certified payroll information periodically, and developing a mobile app for farmworkers to report their wages and hours, could give WHD early warning of potential violations as well as provide workers with a way to anonymously report violations.

Monitoring working conditions in the fields has always been challenging and is becoming more and more difficult. The Wage and Hour Division needs more investigators, more funding, and more effective strategies to protect farmworkers, which needs to be bolstered by political will in the legislative and executive branches to overcome opposition from those who believe that farm employers are somehow above needing to follow basic workplace laws. This is driven by a narrative of agricultural “exceptionalism”—which is the belief that agriculture is such a different industry with such unique operations that it lies outside of—and thus should not be regulated by—the usual labor and employment law framework. This view unfortunately has a well-established and harmful foothold in our laws and politics, resulting in legal carveouts of farmworkers from many of the bedrock labor standards protections that have covered workers outside of agriculture for decades at the federal and state level. Over the past half century, public acceptance of agricultural exceptionalism has finally begun to erode, but the job is far from complete. Additional enforcement resources are needed to ensure that farm employers play by the rules and that all farmworkers are guaranteed their basic rights for fair pay and working conditions.

Are farmworkers overpaid? Dispelling the myths about farmworker wages and the H-2A visa program

The public discourse around the wage of farmworkers has recently reached a fever pitch; with farm employers and industry associations arguing that the wages of farmworkers—but particularly temporary migrant farmworkers in the H-2A visa program—have risen too quickly and are out of control. As a response, farm employers and industry associations have called on and lobbied Congress to take action to reduce the required wage rates for H-2A farmworkers, known as the Adverse Effect Wage Rate (AEWR) and sued the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) to invalidate the AEWR, which is designed to reflect the current wages in the farm labor market, with the intention of protecting wage standards for all U.S. and migrant farmworkers in the United States. This effort it underway despite the fact that, as noted above, most farmworkers are not covered by many basic federal labor and wage and hour law protections that other workers have, such as overtime pay.

The most recent attempt to reduce the value of the AEWR has occurred in just the past month, with legislators in the House and Senate each proposing legislation to use the Congressional Review Act (CRA) to repeal the most recent update to the AEWR from DOL that went into effect on March 30, 2023—which made only a slight change to the existing methodology, impacting very few farmworkers and a miniscule share of farm employers’ labor costs. This section will briefly discuss the state of farmworker wages, take a historical look at the value of the AEWR over the past decade and in the most recent years, and discuss the recent proposal to use the CRA to repeal the latest iteration of the AEWR.

Farmworkers earn lower wages than workers in other low-wage industries

The most reliable data on farmworker earnings comes from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), which conducts the Farm Labor Survey (FLS), the results of which are published twice a year in USDA’s Farm Labor report series, with data reported for reference weeks in January, April, July, and October.65 As noted above, the minimum wage that employers are required to pay to H-2A farmworkers is in most cases the Adverse Effect Wage Rate (AEWR),66 which varies by region and is set by DOL, based on the average hourly earnings of nonsupervisory field and livestock workers, as reported by farm operators in the FLS. DOL uses the FLS data to set H-2A wages so they reflect current real-world trends in the farm labor market.

Despite some documented real increases in wages the past few years,67 the latest data show the wages of farmworkers are extremely low by any measure, even when compared with similarly situated nonfarm workers and workers with the lowest levels of education (see Figure L).

The farmworker wage gap in 2022: Farmworkers earn very low wages compared with other workers: Average hourly wage rate for nonsupervisory farmworkers nationwide compared with average hourly wages of other workers, 2022

| Type | Amount | |

|---|---|---|

| Nonsupervisory farmworkers | $16.62 | |

| Workers with less than HS | $16.52 | |

| Workers with HS diploma only | $21.94 | |

| Nonsupervisory nonfarm | $27.56 | |

| All workers | $32.00 | |

Notes: All values are for 2022 and in 2022 dollars. HS = high school. Nonsupervisory nonfarm workers’ wage represents the average hourly earnings of production and nonsupervisory employees, total for the private sector, not seasonally adjusted. Nonsupervisory farmworkers’ wage is the gross average hourly wage of field and livestock workers. Data for all workers, and for workers with a high school diploma and less than high school, can be found at the Economic Policy Institute State of Working America Data Library.

Source: Author’s analysis of USDA Farm Labor Survey data and nonfarm wage data from the BLS Current Employment Statistics survey; EPI analysis of CPI-ORG microdata.

In 2022, the average wage of all nonsupervisory farmworkers (i.e. combined field and livestock workers, to use USDA’s terminology and category) was $16.62 per hour, according to USDA, which was a 7% increase in nominal terms from what farmworkers earned per hour in 2021, which was $15.56 per hour. However, after adjusting for inflation, the real value of the 2021 average hourly wage of farmworkers was $16.67 per hour—meaning that the real value of the average farmworker wage declined by 5 cents from 2021 to 2022, i.e. from $16.67 in 2021 to $16.62 in 2022.68

The 2022 average farmworker wage of $16.62 per hour is also just half (52%) of the average hourly wage for all workers in 2022, which stands at $32.00 per hour. The average hourly wage for production and nonsupervisory nonfarm workers—the most appropriate cohort of nonagricultural workers to compare with farmworkers—was $27.56.

In other words, farmworkers earned just under 60% of what production and nonsupervisory workers outside of agriculture earned. USDA has referred to this wage gap between farmworker and nonfarm worker wages as “slowly shrinking, but still substantial.”69 In 2022, the farmworker wage gap remained substantial and virtually unchanged from the previous two years.70

Farmworkers have very low levels of educational attainment. According to the NAWS, 26% completed the 10th, 11th, or 12th grade, and 14% completed some education beyond high school.71 Farmworkers earn the same or less than the two groups of workers with the lowest levels of education in the United States: Nonsupervisory farmworkers at $16.62 per hour earned 10 cents an hour more than the average wage earned by workers without a high school diploma ($16.53), nearly an identical wage, and farmworkers earned $5.32 less per hour than the average wage earned by workers with only a high school diploma ($21.94).

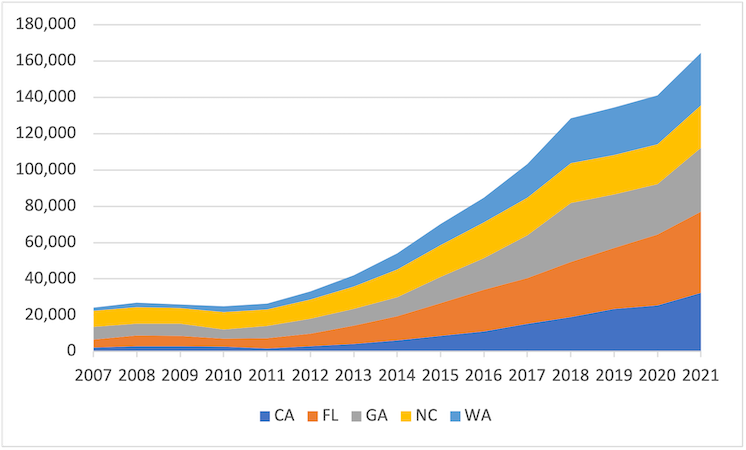

When it comes to the AEWR, the required AEWR wage varies by state. In 2022, it ranged from $11.99 per hour to $17.51. That means that for many H-2A workers, the wage they earned was even lower than the national average wage for all nonsupervisory farmworkers in 2022—meaning the gap between what many H-2A farmworkers and nonagricultural workers earn is even wider.