Black women face a persistent pay gap, including in essential occupations during the pandemic

This year, Black Women’s Equal Pay Day arrives 10 days earlier than in 2020 (August 13). If this seems inconsistent with current realities, it is. That’s because the August 3, 2021, date is based on the comparison of median annual earnings for full-time, year-round workers reported in the 2020 Annual Social and Economic Supplement of the Current Population Survey (CPS). Since the reference year in that survey is the previous year—2019—the earlier date is more a statement about pay equity during the pre-COVID period of historically low unemployment than the impact of the pandemic.

Based on hourly wages available for 2020, the pandemic’s effect on pay inequality in 2020 is challenging to interpret since job losses were concentrated among low-wage occupations, which has the effect of skewing the distribution toward a higher average that is less representative of the workforce as a whole. These lower-paying jobs were concentrated in leisure and hospitality and education and health services—industries that employ a disproportionate share of women.

In fact, the pandemic’s effect on pay equity during 2020 is less about a relative difference in dollars per hour and more a matter of a disproportionate share of women—and Black women in particular—becoming unemployed and thus wageless. Nearly one in five Black women (18.3%) lost their jobs between February 2020 and April 2020, compared with 13.2% of white men (see figure below). As of June 2021, Black women’s employment was still 5.1 percentage points below February 2020 levels, while white men were down 3.7 percentage points.

A more comprehensive look at employment: Employment-to-population ratios for select workers by race/ethnicity and gender, February 2020, April 2020, October 2024, and November 2024

| characteristic | February 2020 | April 2020 | October 2024 | November 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White men | 69.6% | 60.5% | 67.6% | 67.5% |

| White women | 56.7% | 47.2% | 55.7% | 55.7% |

| Black men | 63.4% | 52.9% | 65.3% | 64.6% |

| Black women | 60.7% | 49.4% | 59.5% | 58.6% |

| Latinx men | 78.3% | 64.3% | 76.5% | 75.8% |

| Latinx women | 58.8% | 44.8% | 58.2% | 58.6% |

Notes: Data are for workers ages 20 and older. Racial and ethnic categories are not mutually exclusive; white and Black data do not exclude Latinx workers of each race. Employment to population levels are labeled for February, April, and the trough in between.

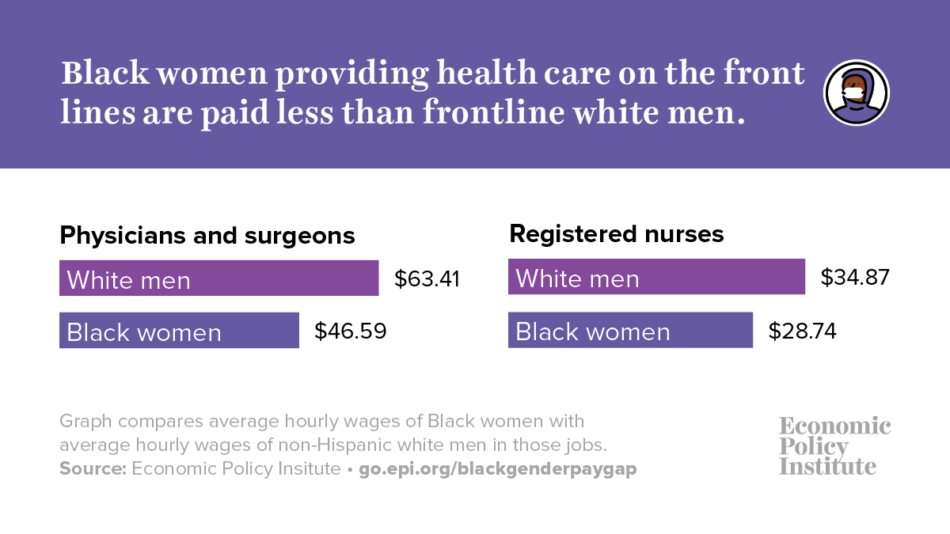

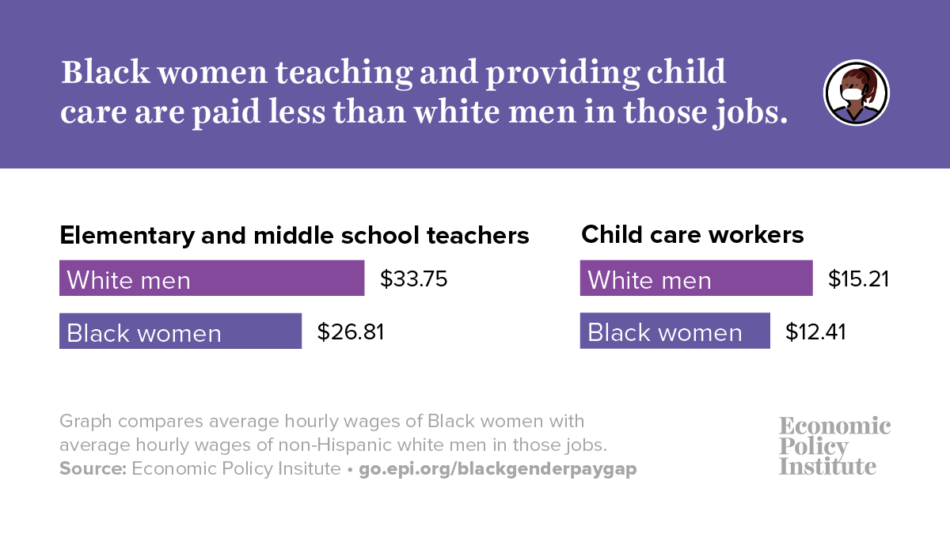

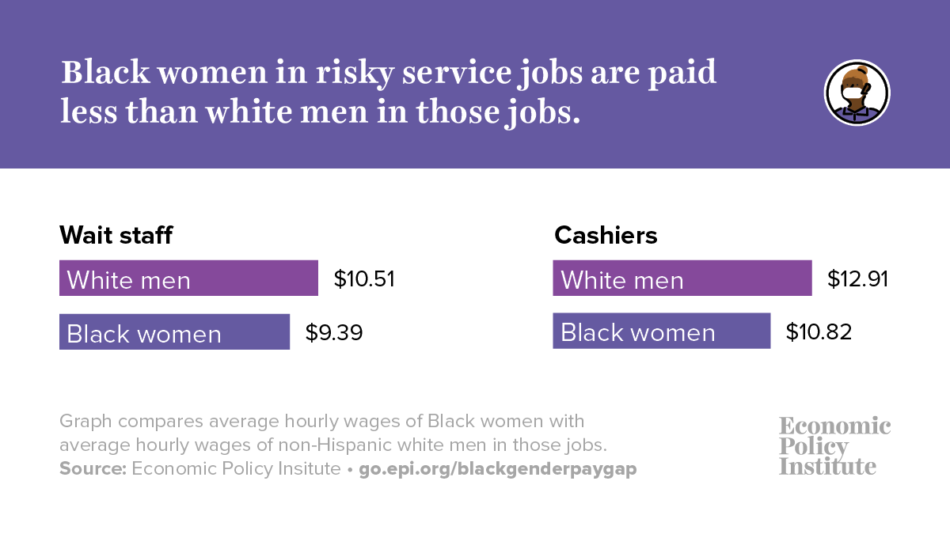

The fact that we are talking about this every year reflects the stubborn, structural nature of pay inequities that is manifold. Occupational segregation limits Black women’s access to higher-paying occupations. But, even when employed in the same occupation, pay discrimination results in lower earnings for women relative to men, including among essential workers as we show below. The lack of a national paid leave policy means that women are more likely to take unpaid time out of the workforce and have breaks in their work and earnings history. The combination of these factors means that, on average, women start their careers with a pay gap that they are never able to close.

The infographics below take a closer look at average hourly earnings of Black women and non-Hispanic white men employed in major occupations at the center of national efforts to address the public health and economic effects of COVID-19, based on our previous analysis of CPS microdata from 2014–2019. These occupations include front-line workers in health care and essential businesses like grocery stores, those who have borne the brunt of job losses in the restaurant industry, and teachers and child care workers. As these figures show, equal pay for Black women workers is long overdue.

Enjoyed this post?

Sign up for EPI's newsletter so you never miss our research and insights on ways to make the economy work better for everyone.