Teachers pay out-of-pocket to keep their classrooms clean of COVID-19: Teachers already spend on average $450 a year on school supplies

“I keep my surfaces as clean as possible, wipe down tables every day, and use sanitizer, but it becomes an expense, because the district doesn’t give us wipes or sanitizer for our classrooms,” Kristin Luebbert, a teacher at the U School in North Philadelphia, recently told The Philadelphia Inquirer. “It’s just a worry—what’s the plan and how are we going to be safe?”

With fears over COVID-19 spreading throughout the nation’s classrooms, there is understandably a push to maintain cleanliness in all schools. Even the Centers for Disease Control weighed in with recommendations for schools and teachers in particular too: clean and disinfect frequently touched surfaces and objects in the classroom.

The question is who’s going to pay for the products needed to protect students and teachers?

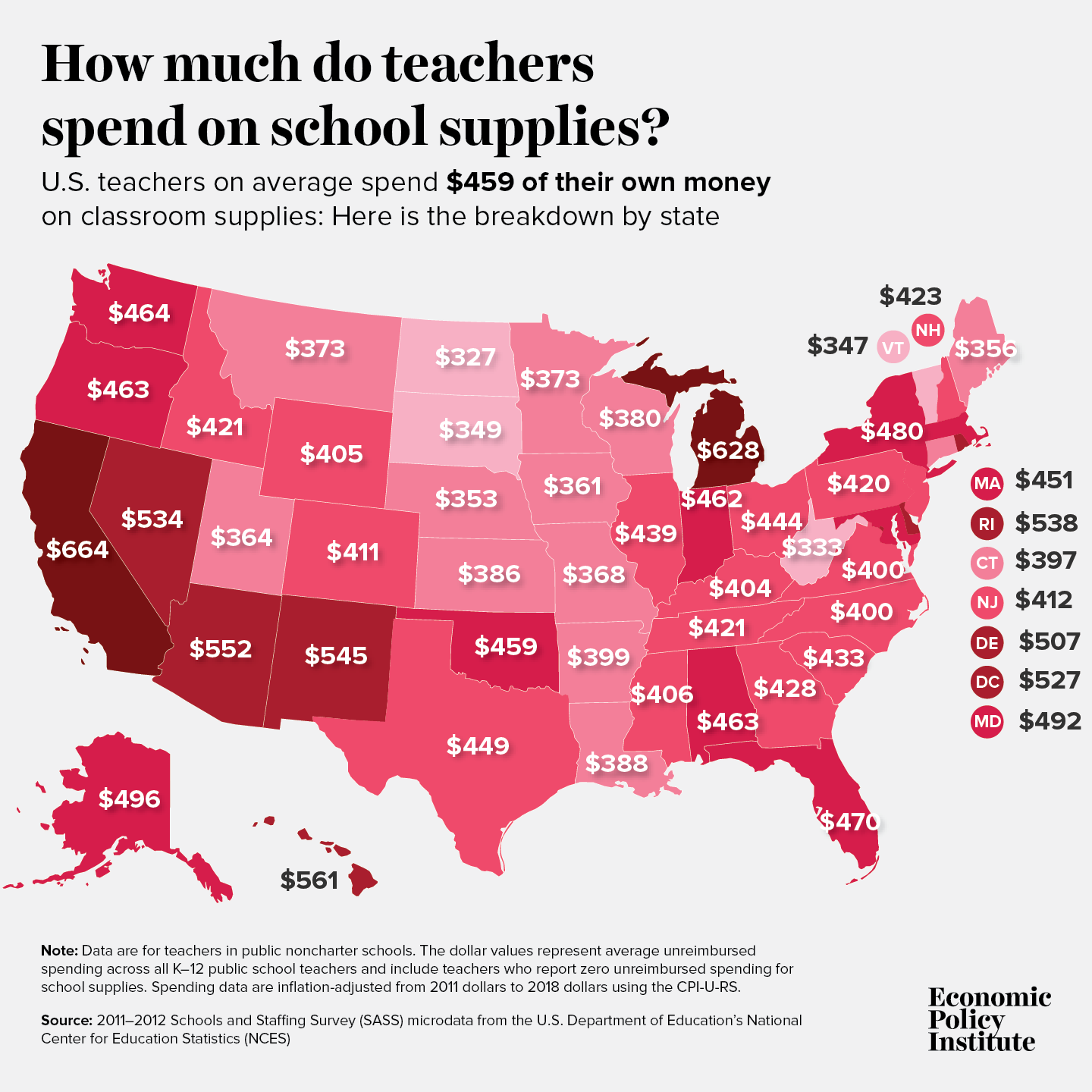

Turns out, some teachers are using their own money to cover the cost of things such as hand sanitizers and wipes, according to some published reports on the issue. That expense is in addition to the, on average, $459 teachers spend on school supplies for which they are not reimbursed (adjusted for inflation to 2018 dollars), found an analysis by Economic Policy Institute economist Emma García.

“What’s ahead for teachers in light of the threat of COVID-19 spreading will only add to the existing challenges and stress,” predicts García. “Teachers already act as first respondents when it comes to children’s basic needs, and schools are the only place where some students can have access to hot meals, medical care, washing their dirty laundry, or even to shelter. These, as well as the expense outlays, are worse in schools serving larger shares of low-income students.”

Michelle Gunderson, who teaches first grade at Nettelhorst School in Chicago’s Lakeview neighborhood and is also on the executive board of the Chicago Teachers Union, told the Chicago Tribune last week that she received a $100 donation from parents to cover the cleaning product costs, but that poorer areas where parents may not be able to afford to contribute presented a bigger, financial burden for teachers in those schools. “This is a big equity issue in Chicago,” she said.

Indeed, García’s analysis found that teachers in high-poverty schools are spending more of their own money on school supplies than are teachers in low-poverty schools.

“That gap may reflect greater needs among students in high-poverty schools and more deficient funding systems for those schools (as our report said, the data do not allow us to decompose the types of expenses or disentangle the reasons why a teacher spent money and was or was not reimbursed for it.),” explains García. “The trend over time could also reflect an uneven influence of the economic cycle (crisis and recovery) across school types. These statistics could be seen as an alert to keep an education approach and an equity approach when allocating supports for schools, teachers and children during the outbreak and when things go back to normal.”

While the spread of COVID-19 will be largely blind to social class, she notes, “those in high-poverty schools may be getting a larger share of its negative education consequences.”

Enjoyed this post?

Sign up for EPI's newsletter so you never miss our research and insights on ways to make the economy work better for everyone.