What this report finds: The vast majority (over 70%) of federal labor standards investigations of farms conducted by the Wage and Hour Division (WHD) of the U.S. Department of Labor detect violations—things like wage theft and inadequate housing, as well as other violations of laws designed to protect farmworkers. Farm labor contractors, the fastest-growing segment of farm employment, are the worst violators, accounting for one-fourth of all federal wage and hour violations detected in agriculture and one-half of violations detected in two of the biggest states for farm employment, California and Florida. A relative handful of “bad apples” account for a large share of all violations and the back wages owed as a result of investigations. However, there is a very low probability—1.1%—that any farm employer will be investigated by WHD in any given year.

Why it matters: Farmworkers—the low-paid workers who are essential to keeping Americans fed during the COVID-19 pandemic—are not being protected effectively by federal labor standards enforcement. Most farmworkers either lack an immigration status or have a temporary status, which makes it difficult in practice for them to complain about workplace violations. And data show that WHD is too underfunded and understaffed to adequately protect workers. This lack of enforcement capacity, combined with the fact that their immigration status makes farmworkers vulnerable to exploitation, means that the violations detected in agriculture by WHD are likely a small share of the actual violations taking place. Farm employers can violate wage and hour laws and reasonably expect that those violations will never be detected.

What we can do about it: Policymakers should provide adequate resources to fund wage and hour staffing and enforcement; enforcement efforts should target the biggest violators—farm labor contractors—as well as repeat violators; and officials should consider stiffer penalties that are sufficient to deter future violations.

Introduction, summary, and findings

Farmworkers in the United States earn some of the lowest wages in the labor market and experience an above-average rate of workplace injuries (Costa 2020; BLS 2020). No one knows the exact number of workers employed for wages on U.S. farms during the year, although there are multiple estimates. The Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) shows that average annual employment of farmworkers who are employed on farms that report to state unemployment insurance (UI) agencies was 1.3 million in 2019 (BLS-QCEW 2020a), but estimated that there were an additional 400,000 “wage and salary” farmworkers not included in QCEW data (BLS-QCEW 2020b), suggesting average employment of 1.7 million in 2019.

The QCEW reports average employment, which underestimates the number of unique farmworkers due to seasonality and turnover. The Census of Agriculture (COA) asks farmers (i.e. farm employers or farm owners) how many workers they employ directly; in 2017, farmers reported hiring 2.4 million farmworkers. However, the COA does not report workers who are brought to farms by nonfarm employers such as nonfarm labor contractors, and double counts workers employed by two farms, so 2.4 million is not a count of unique farm workers. The Current Population Survey included a December supplement through the 1980s, and it reported about 2.5 million farmworkers when annual average employment ranged between about 1.1 million to 1.3 million, suggesting about two unique workers per year-round equivalent job, or 2.5 million to 3.4 million workers today based on QCEW data (Rural Migration News 2020b).

The U.S. Department of Labor’s National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS) reports the characteristics of crop farmworkers, excluding those who are migrants employed through the H-2A temporary work visa program for agriculture (a “nonimmigrant” visa program), but not their number. H-2A is a temporary work visa program that allows farm employers

to hire migrant guestworkers if they anticipate a shortage of U.S. workers to fill temporary and seasonal jobs. Half of the non-H-2A crop workers were unauthorized immigrants in 2015–2016 (U.S. DOL-ETA 2018), and there were more than 200,000 H-2A workers employed in the United States in 2019, who worked for an average of six months out of the year, representing roughly one-tenth of farmworkers employed on U.S. crop farms (Costa and Martin 2020). Both unauthorized and H-2A workers have limited labor rights and are vulnerable to wage theft and other abuses due to their immigration status (Bernhardt et al. 2009; Apgar 2015). This leaves 40% of the workforce who are U.S. citizens and legal immigrants with full rights and agency in the labor market, so most farmworkers are vulnerable to violations of their rights because of their immigration status.

The U.S. Department of Labor’s (DOL) Wage and Hour Division (WHD) is the federal agency that protects the rights of farmworkers in terms of wage and hour laws—also known as employment laws—including those that protect H-2A “guest” workers. WHD labor standards enforcement actions are intended to ensure that the rights of workers are protected, and to level the playing field for employers, so that employers who underpay workers or engage in other cost-reducing behavior in violation of employment laws do not gain a competitive advantage over law-abiding employers. WHD aims to “promote and achieve compliance with labor standards to protect and enhance the welfare of the nation’s workforce” by enforcing 13 federal labor standards laws, including the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), which requires minimum wages and overtime pay, and regulates the employment of workers who are younger than 18, as well as the Family and Medical Leave Act, and laws governing government contracts, consumer credit, and the use of polygraph testing, etc. (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020c).

WHD also enforces two laws and their implementing regulations specific to agricultural employment. One is the Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act (MSPA), the major federal law that protects U.S. farmworkers. The other is the statute that establishes the H-2A program, a temporary work visa program that allows farm employers to hire migrant guestworkers if they anticipate a shortage of U.S. workers to fill temporary and seasonal jobs.

Federal labor law exempts farmworkers from some basic protections that cover most other workers in the U.S. labor market, including from the National Labor Relations Act—the federal law that provides the right to form and join unions, and to engage in protected, concerted activities to improve workplace conditions. Farmworkers are covered by the FLSA, but not the FLSA’s overtime provisions that require most workers to be paid time and a half after working eight hours in a day or 40 hours in a week.1

The WHD in 2019 had just under 1,500 employees, including 780 investigators, and a budget of $229 million to investigate 10.2 million U.S. establishments with 148 million employees (BLS-QCEW 2020a; U.S. DOL 2020; U.S. DOL-WHD 2020e). The number of workers that each WHD investigator is responsible for has risen dramatically. In 1978, there was one WHD investigator for every 69,000 workers; by 2018, one investigator was responsible for 175,000 workers (Hamaji et al. 2019), highlighting persistent WHD underfunding and understaffing.

WHD may order employers to pay back wages owed to underpaid employees, file suits to recover back wages and an equal amount as liquidated damages, and assess civil money penalties that aim to remove the incentive to violate employment laws. WHD also may seek injunctive relief from federal courts to mandate employer compliance and prosecute egregious violations criminally. When investigating workplace violations, WHD does not take immigration status into account, and can award back pay to farmworkers who are not authorized to be employed in the United States.

Ensuring compliance with labor standards in a low-wage sector with vulnerable and exploitable workers such as agriculture is difficult for any enforcement agency, but especially the underfunded WHD. Former WHD Administrator David Weil concluded that there “will never be sufficient resources to staff agencies to the level required to assure complete compliance with workplace laws, so there will always be a need for enforcement agencies to use their [limited] resources to achieve greatest impact.” (Weil 2018, 20). As a result, Weil introduced strategic enforcement, moving from responding to individual worker complaints to having half or more of WHD investigations be proactive or directed at firms likely to violate wage and hour laws. WHD also used such enforcement tools as the “hot goods” provision, which allows WHD to prohibit the shipment and distribution of goods produced in violation of FLSA’s minimum wage, overtime, or child labor requirements (Weil 2014a).

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the already-extreme vulnerabilities of farmworkers, who are considered “essential” workers and who work in person rather than remotely. Federal and state workplace safety agencies, as well as employer associations and buyers of farm commodities, have developed guidelines to protect essential workers by reorganizing work, travel, and housing, and providing workers with protective personal equipment. However, following these federal guidelines is not mandatory, and there are widespread concerns that limited access to the social safety net, combined with crowded conditions at work and in housing, could encourage sick employees to work and allow COVID-19 to spread rapidly among farmworkers (Costa and Martin 2020; Botts and Cimini 2020; Bottenmiller Evich, Bustillo, and Crampton 2020). COVID-19 cases are not always reported by industry and occupation, but media reports suggest there have been numerous outbreaks among farmworkers, and food processing and meatpacking workers (Dorning and Skerritt 2020; Douglas 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic makes it more important than ever that farm employers comply with labor standards and protect farmworkers

This report analyzes federal data from WHD databases on wage and hour violations to understand labor standards enforcement efforts in the agricultural sector. The data represent only WHD investigations and violations of the law detected by WHD, but not all labor and employment law violations in agriculture. The immigration status of farmworkers, fear of retaliation and deportation, and even the perception that WHD will not take action or will fail to obtain meaningful remedies can contribute to farmworkers not reporting violations.

We analyze data on back wages and civil money penalties (CMPs) that may reflect negotiations and settlements between WHD and farm employers, which means that WHD investigators initially may have sought more back wages or higher CMPs. We also do not know whether the back wages or higher CMPs assessed eventually were paid to workers.

This report does not review health and safety issues on farms or analyze the limited enforcement data from the DOL’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), which enforces the Occupational Health and Safety Act.2 It deals only with federal enforcement, not the enforcement of state labor and employment laws that may provide more protections for farmworkers, as in California and New York. Some state governments do very little to enforce state wage and hour laws—or nothing at all—and in these states, the federal WHD may be the only government agency enforcing employment laws on farms, which may influence where WHD focuses its efforts geographically.

The purpose of this report is to analyze enforcement data to help stakeholders better understand the results of WHD enforcement, including where violations occurred, which laws were violated, and the penalties that were assessed over the past two decades. We hope the analysis will inform and spark a discussion about how to improve labor standards enforcement on farms, and help increase protections for farmworkers.

Major findings

Following are seven major findings from the report:

- Investigations of employers that violate federal wage and hour laws designed to protect farmworkers detect millions in wage theft every year and lead to millions in civil money penalties against agricultural employers.

- The U.S. Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division (WHD) conducted more than 31,000 investigations of U.S. employers in agriculture between fiscal years 2000 and 2019, an average of 1,500 per year. As a result of these investigations, employers were ordered to pay $76 million in back wages to 154,000 farmworkers and to pay $63 million in civil money penalties for violations (in constant 2019 dollars). In 2019, average back wages owed per worker were $572 for violations of the Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act, $485 for violations of the H-2A visa program, and $813 for violations of the Fair Labor Standards Act. Violations of these laws include things like wage theft and providing inadequate housing as well as violations related to transportation, employer disclosures, and record-keeping.

- In 2019, WHD investigators found that agricultural employers owed farmworkers a total of $6.0 million in back wages and assessed violating employers $6.3 million in civil money penalties. Both back wages owed and civil money penalties assessed as a result of investigations peaked in fiscal year 2013, at $8.5 and $8.0 million, respectively (all in constant 2019 dollars).

- In 2019, WHD investigators found that employers owed $1.3 million in back wages to 2,300 workers based on violations of the Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act (MSPA), which is the major federal law that protects U.S. farmworkers, and these employers were assessed $2.9 million in civil money penalties for MSPA violations (all in constant 2019 dollars). The year 2019 was the peak year for both back wages owed and civil money penalties assessed for MSPA violations detected by investigations.

- In 2019, WHD investigators found that employers owed $2.4 million in back wages to 5,000 workers based on violations of the H-2A visa program (nonimmigrant visas for temporary or seasonal farmworkers); employers were assessed $2.8 million in civil money penalties for H-2A violations. In 2019, the number of violations detected in the H-2A program by WHD was a record 12,000. Both back wages owed and civil money penalties assessed for H-2A violations peaked in fiscal year 2013, at $4.9 and $6.6 million, respectively (all in constant 2019 dollars).

- Agriculture accounts for a much higher share of investigations and violations than its share of total U.S. employment. Average farmworker employment among employers that report to state unemployment insurance agencies was 1.3 million, about 1% of total U.S. employment in 2019. However, over the past 15 years, agriculture accounted for 7% of all federal wage and hour investigations and 3% of the 10 million violations found—three times agriculture’s share of employment.

- The back wages recovered for farmworkers whose rights have been violated may just be the tip of the iceberg since WHD is underfunded and understaffed. The number of WHD investigations in U.S. agriculture fell to 1,125 in 2019, an average of less than 100 a month, and less than half of the 2,431 investigations in 2000. Given that WHD investigates roughly 1,200 agricultural employers each year out of the 107,000 farm employers that report to state unemployment insurance agencies, a farm employer’s probability of being investigated in any given year is 1.1%. Funding for WHD and the number of WHD investigators has declined in recent years, and the 780 investigators in 2019 were fewer than five decades ago, helping to explain fewer investigations.

- Despite the reduction in the number of investigations and staff at WHD, the vast majority of investigations of farm employers detect violations, a sign that these employers are not complying with federal wage and hour laws. Some 70% of investigations conducted by WHD in agriculture detected violations, including 40% that detected one to four violations and 30% that detected five or more violations.

- Farm labor contractors—nonfarm employers acting as staffing firms for farm employers—were the most egregious violators between 2005 to 2019. These employers represent 14% of agricultural employment nationwide but accounted for 24% of all agricultural violations from 2005 to 2019. Farm labor contractors also represented a higher share of agricultural violations than their share of employment in the two major farm labor states, California and Florida—where they accounted for approximately half of all violations over the 2005–2019 period. Farmworkers who are employed by farm labor contractors are more likely to suffer wage and hour violations than those who are hired directly by farms.

- Violations of federal wage and hour laws vary across areas and commodities. The share of wage and hour violations detected by county and commodity does not necessarily correspond to the share of agricultural employment in that county or commodity. In other words, some counties with relatively lower agricultural employment nevertheless may have a disproportionally high share of violations, and vice versa.

- A number of “bad apple” employers make life tough for farmworkers. Among the employers that were investigated, the 5% that committed the most violations accounted for half or more of all violations in a particular agricultural industry or commodity, including among farm labor contractors.

Questions for further investigation

Our analysis raises several key questions that merit further investigation with respect to better protecting farmworkers, including:

- Does the low probability of being investigated encourage violations of employment laws? Since only 1.1% of farm employers are investigated in any given year, farm employers reasonably can expect they will never be investigated.

- Without increased funding for WHD, could changes in enforcement strategy improve compliance and worker protections? What is the optimal balance between investigations in areas with more and fewer farmworkers, and between complaint-driven and strategic enforcement that targets likely violators? What are the lessons of WHD’s strategic enforcement strategy during Administrator David Weil’s tenure between 2014 and 2016?

- Are the penalties assessed by WHD for violations sufficient to change behavior and deter others from violating employment laws? If not, what penalties would encourage compliance and deter violations?

- What can be done to improve compliance among the bad apple employers and farm labor contractors who account for the most violations? Should public policy aim to reduce the growth of the farm labor contractor model of farm employment?

- Could more education of workers and employers improve compliance?

Recommendations

We offer the following recommendations for enforcement agencies that could improve compliance with employment laws and better protect farmworkers:

- FLCs and farms that use FLCs deserve increased scrutiny. Given their disproportionate share of violations, compliance could be incentivized with:

- larger fines and more significant sanctions, and making other employers aware of them

- adequate enforcement of the joint employment standard under the FLSA to encourage farms to ensure that the FLCs who bring workers to their farms are in compliance.

- Among all employers and FLCs, examining whether the severity of sanctions is sufficient; increasing the value of civil money penalties should be considered in order to shift penalties from a cost of doing business to an incentive for compliance.

- WHD should continue to assess and refine strategic enforcement strategies that aim to improve compliance among employers prone to violate employment laws.

- Repeat violators of employment laws could be required to submit certified payroll data to WHD (as the Davis-Bacon Act requires of government contractors), and be subjected to random payroll audits.

- Statistical analysis of labor standards enforcement data can formalize investigator rules of thumb about which employers are most likely to violate employment laws, and help investigators more quickly detect irregularities in payroll data. For example, databases that record the average productivity of workers would be helpful to determine whether “ghost” farmworkers on employer payrolls explain extra-high hourly earnings.

- More could be done to build on the good work done by advocates and unions to educate farmworkers about their rights and the process of reporting violations, perhaps with new and innovative methods like mobile phone apps.

WHD funding and enforcement: Investigations in agriculture and total fines between fiscal years 2000 and 2019

The analysis in this section is based on aggregate data from the enforcement database of the U.S. Department of Labor’s (DOL) Wage and Hour Division (WHD). WHD conducted more than 31,000 investigations in U.S. agriculture between fiscal years 2000 and 2019, an average of 1,500 per year, and ordered $76 million to be paid in back wages to 154,000 farmworkers, and assessed $63 million in civil money penalties for violations (in constant 2019 dollars) (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020a).

Figure A shows a clear downward trend in the number of WHD investigations at agricultural worksites over the past two decades, from more than 2,000 a year in the early 2000s to 1,100 per year the last two fiscal years.

Wage and Hour Division investigations of agricultural employers, fiscal years 2000–2019

| Fiscal Year | Inspections of agricultural employers |

|---|---|

| 2000 | 2,431 |

| 2001 | 2,300 |

| 2002 | 2,176 |

| 2003 | 1,495 |

| 2004 | 1,630 |

| 2005 | 1,449 |

| 2006 | 1,410 |

| 2007 | 1,666 |

| 2008 | 1,600 |

| 2009 | 1,377 |

| 2010 | 1,277 |

| 2011 | 1,527 |

| 2012 | 1,659 |

| 2013 | 1,673 |

| 2014 | 1,430 |

| 2015 | 1,361 |

| 2016 | 1,275 |

| 2017 | 1,307 |

| 2018 | 1,076 |

| 2019 | 1,125 |

Source: Authors’ analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, Agriculture data table (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020a).

What explains fewer investigations of farm employers? While labor enforcement priorities vary by administration, funding for WHD has lagged behind the growth of the U.S. labor force. In inflation-adjusted dollars, WHD’s budget in 2020 was $13 million less than it was in 2012.3 Figure B shows that in 2019 there were only 780 WHD investigators enforcing federal labor standards, 32 fewer than in 1973 (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020e). Hamaji et al. (2019) note that in 1978, there was one WHD investigator for every 69,000 U.S. workers; by 2018, there was one investigator for every 175,000 U.S. workers.

Number of Wage and Hour Division investigators, U.S. Department of Labor, 1973–2019

| Year | Investigators on board at years’ end |

|---|---|

| 1973 | 812 |

| 1974 | 869 |

| 1975 | 921 |

| 1976 | 964 |

| 1977 | 980 |

| 1978 | 1,232 |

| 1979 | 1,087 |

| 1980 | 1,059 |

| 1981 | 953 |

| 1982 | 914 |

| 1983 | 928 |

| 1984 | 916 |

| 1985 | 950 |

| 1986 | 908 |

| 1987 | 951 |

| 1988 | 952 |

| 1989 | 970 |

| 1990 | 938 |

| 1991 | 865 |

| 1992 | 835 |

| 1993 | 804 |

| 1994 | 800 |

| 1995 | 809 |

| 1996 | 781 |

| 1997 | 942 |

| 1998 | 942 |

| 1999 | 938 |

| 2000 | 949 |

| 2001 | 945 |

| 2002 | 898 |

| 2003 | 850 |

| 2004 | 788 |

| 2005 | 773 |

| 2006 | 751 |

| 2007 | 732 |

| 2008 | 731 |

| 2009 | 894 |

| 2010 | 1,035 |

| 2011 | 1,024 |

| 2012 | 1,067 |

| 2013 | 1,040 |

| 2014 | 976 |

| 2015 | 995 |

| 2016 | 974 |

| 2017 | 912 |

| 2018 | 835 |

| 2019 | 780 |

Note: Numbers represent Wage and Hour Division investigators on staff at the end of each year.

Source: Authors' analysis of Wage and Hour Division data on the number of investigators (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020e).

Nonetheless, Figure C shows that the total back wages owed for all violations of federal employment laws has been on a generally upward trend, peaking at $8.4 million in FY2013, the same year that civil money penalty assessments peaked at $8.0 million. Annual back wages and CMPs were between $3.8 million and $6.7 million over the past five years.4 Figure D shows that the number of farmworkers who were owed back wages peaked at 12,000 in FY2014, and was just under 9,000 in FY2019.

Back wages and civil money penalties assessed (in millions of dollars) against agricultural employers by the Wage and Hour Division, fiscal years 2000–2019

| Fiscal year | Back wages | Civil money penalties |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | $1.98 | $2.04 |

| 2001 | 2.50 | 1.83 |

| 2002 | 2.89 | 1.69 |

| 2003 | 3.40 | 1.58 |

| 2004 | 1.65 | 2.24 |

| 2005 | 1.75 | 1.40 |

| 2006 | 2.15 | 1.03 |

| 2007 | 3.94 | 1.79 |

| 2008 | 2.52 | 1.60 |

| 2009 | 1.68 | 1.50 |

| 2010 | 3.71 | 1.30 |

| 2011 | 3.25 | 2.21 |

| 2012 | 5.88 | 5.10 |

| 2013 | 8.45 | 8.02 |

| 2014 | 4.87 | 3.35 |

| 2015 | 4.66 | 5.46 |

| 2016 | 5.16 | 3.77 |

| 2017 | 5.26 | 4.53 |

| 2018 | 4.28 | 6.66 |

| 2019 | 6.06 | 6.33 |

Note: Data are inflation adjusted to 2019 dollars.

Source: Authors’ analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, Agriculture data table (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020a).

Employees receiving back wages resulting from Wage and Hour Division investigations of agricultural employers, fiscal years 2000–2019

| Fiscal Year | Employees receiving back wages |

|---|---|

| 2000 | 5,255 |

| 2001 | 9,356 |

| 2002 | 5,823 |

| 2003 | 7,778 |

| 2004 | 3,711 |

| 2005 | 3,984 |

| 2006 | 2,968 |

| 2007 | 8,670 |

| 2008 | 5,399 |

| 2009 | 5,527 |

| 2010 | 8,601 |

| 2011 | 6,567 |

| 2012 | 11,068 |

| 2013 | 11,847 |

| 2014 | 12,031 |

| 2015 | 10,025 |

| 2016 | 10,549 |

| 2017 | 7,304 |

| 2018 | 9,015 |

| 2019 | 8,972 |

Source: Authors’ analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, Agriculture data table (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020a).

Three states with large agricultural sectors accounted for 41% of WHD agricultural investigations over the past two decades: Florida had 18%, Texas 12%, and California 11%. North Carolina and New York each had 5% of investigations, and Georgia, New Jersey, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, and Virginia each accounted for 3%.

Violations of the Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act

Over the past two decades, back wages owed to farmworkers and civil money penalties assessed have been rising for violations of the United States’ main law protecting farmworkers, and for violations of regulations governing H-2A, the main temporary work visa program for farmworkers.

About 45% of the agricultural investigations over the past two decades found violations of the Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act (MSPA), the major federal law that protects U.S. farmworkers. In the peak year of FY2014, more than half of investigations revealed violations of MSPA; there were an average 14 violations on the farms with MSPA violations. Over the past 20 years, the average number of MSPA violations per farm with violations was eight.

Table 1 presents data on MSPA investigations, violations, and penalties, and shows that back wages owed to workers for MSPA violations peaked at $1.3 million in FY2019, when civil money penalties for MSPA violations also peaked at $2.9 million. In FY2019, employers were ordered to provide back pay to 2,253 workers, an average of about $570 each.

Enforcement of the Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act (MSPA): Back wages and civil money penalties assessed by the Wage and Hour Division resulting from violations of MSPA, fiscal years 2000–2019

| Fiscal year | Cases with violations | Total violations under MSPA | Ave violations per case | Employees receiving back wages | Back wages ($2019) | Average back wages owed per employee ($2019) | Civil monetary penalties assessed ($2019) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total or average | 14,094 | 119,045 | 8 | 52,760 | $10,012,400 | $190 | $24,718,400 |

| 2000 | 853 | 4,422 | 5 | 1,114 | $156,200 | $140 | $1,295,900 |

| 2001 | 941 | 10,745 | 11 | 6,356 | $532,900 | $84 | $1,061,900 |

| 2002 | 948 | 5,994 | 6 | 1,835 | $552,500 | $301 | $1,116,400 |

| 2003 | 740 | 6,008 | 8 | 1,994 | $371,100 | $186 | $836,200 |

| 2004 | 794 | 4,295 | 5 | 1,129 | $369,800 | $328 | $1,283,700 |

| 2005 | 616 | 3,430 | 6 | 1,330 | $129,200 | $97 | $772,500 |

| 2006 | 615 | 3,105 | 5 | 1,007 | $193,600 | $192 | $776,500 |

| 2007 | 812 | 5,350 | 7 | 1,497 | $222,000 | $148 | $1,460,500 |

| 2008 | 747 | 5,275 | 7 | 2,557 | $367,700 | $144 | $909,800 |

| 2009 | 636 | 4,979 | 8 | 2,061 | $390,100 | $189 | $960,700 |

| 2010 | 626 | 4,876 | 8 | 1,883 | $379,700 | $202 | $761,900 |

| 2011 | 654 | 5,578 | 9 | 2,558 | $461,300 | $180 | $1,008,700 |

| 2012 | 767 | 7,129 | 9 | 3,688 | $841,800 | $228 | $1,156,500 |

| 2013 | 822 | 8,255 | 10 | 4,336 | $699,700 | $161 | $992,300 |

| 2014 | 756 | 10,745 | 14 | 6,213 | $802,700 | $129 | $1,028,800 |

| 2015 | 707 | 7,802 | 11 | 3,569 | $695,200 | $195 | $905,100 |

| 2016 | 608 | 7,696 | 13 | 3,792 | $724,700 | $191 | $1,031,800 |

| 2017 | 548 | 3,876 | 7 | 1,274 | $260,400 | $204 | $1,682,400 |

| 2018 | 492 | 4,905 | 10 | 2,314 | $573,000 | $248 | $2,801,500 |

| 2019 | 412 | 4,580 | 11 | 2,253 | $1,288,800 | $572 | $2,875,400 |

Note: Dollar amounts reported in this table have been adjusted for inflation to constant 2019 dollars using the CPI-U-RS. As a result, the dollar amounts presented here may differ from the amounts reported in the source data. Totals may not sum due to rounding.

Source: Authors’ analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, Agriculture data table (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020a).

Table 1 also shows that the total back wages owed and CMPs assessed for MSPA violations have fluctuated quite a bit over the past two decades, but increased significantly in FY2019, when back wages peaked at over $1 million for the first time. Over that time frame, WHD assessed nearly $25 million in CMPs for MSPA violations, which exceeded the amount of back wages owed to workers for MSPA violations, $10 million.5

Violations of the H-2A regulations

WHD enforces H-2A regulations that protect labor standards for migrant workers with H-2A visas and U.S. workers vis-à-vis the H-2A program. The H-2A workers’ share of the total farm labor workforce has grown rapidly over the past decade. In 2019, more than 200,000 H-2A workers were employed in the United States, for an average of six months each.6 Numerous reports from advocates, journalists, and government audits have revealed violations of employment laws that protect H-2A workers, who rarely complain because they lose their right to be in the United States if they lose their jobs (see, for example, Garrison, Bensinger, and Singer-Vine 2015; GAO 2017; Bauer and Stewart 2013). This means the H-2A violations detected by WHD investigators likely underreport the true extent of wage and hour violations by H-2A employers.7

About 11% of the agricultural investigations conducted over the past two decades found employer violations of H-2A regulations. The share of investigations that detect violations is rising, reaching 38% in FY2019, while there was an average of 34 violations per investigation that found at least one H-2A violation.

Table 2 shows that back wages owed to workers based on H-2A violations (which may have been owed to H-2A workers and/or U.S. or unauthorized workers) peaked at $4.9 million in FY2013, while CMPs for H-2A violations peaked in the same year at $6.6 million. The number of workers receiving back wages for H-2A violations peaked at almost 5,000 in FY2019, when the average employee who received back wages for an H-2A violation was awarded $485. The highest back wages assessed per employee was in FY2013, when an average of $1,100 was owed to each of the 4,400 workers who were owed back pay. Over the past two decades, the total CMPs assessed by WHD amounted to more than $31 million for H-2A violations, which exceeded total back wages of more than $24 million.8

Enforcement of the H-2A visa program: Back wages and civil money penalties assessed by the Wage and Hour Division resulting from H-2A violations, fiscal years 2000–2019

| Fiscal year | Cases with violations | Total violations under H-2A | Average violations per case | Employees receiving back wages | Back wages ($2019) | Average back wages per employee ($2019) | Civil monetary penalties assessed ($2019) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total or average | 3,343 | 113,836 | 34 | 41,869 | $24,276,900 | $580 | $31,268,700 |

| 2000 | 68 | 1,100 | 16 | 307 | $136,800 | $446 | $203,400 |

| 2001 | 102 | 9,739 | 95 | 1,185 | $675,000 | $570 | $374,300 |

| 2002 | 121 | 3,606 | 30 | 1,043 | $289,800 | $278 | $247,100 |

| 2003 | 76 | 3,440 | 45 | 937 | $502,700 | $537 | $433,400 |

| 2004 | 79 | 1,910 | 24 | 560 | $189,100 | $338 | $242,000 |

| 2005 | 73 | 2,415 | 33 | 947 | $476,400 | $503 | $375,200 |

| 2006 | 86 | 1,084 | 13 | 265 | $277,600 | $1,048 | $73,600 |

| 2007 | 95 | 3,270 | 34 | 1,826 | $544,000 | $298 | $95,700 |

| 2008 | 114 | 3,314 | 29 | 1,064 | $762,400 | $717 | $524,400 |

| 2009 | 117 | 4,152 | 35 | 1,487 | $478,700 | $322 | $369,500 |

| 2010 | 100 | 3,730 | 37 | 954 | $436,200 | $457 | $419,600 |

| 2011 | 170 | 5,987 | 35 | 1,548 | $926,600 | $599 | $889,500 |

| 2012 | 216 | 10,214 | 47 | 3,228 | $2,014,000 | $624 | $3,644,900 |

| 2013 | 232 | 11,171 | 48 | 4,440 | $4,889,800 | $1,101 | $6,565,400 |

| 2014 | 173 | 6,954 | 40 | 2,971 | $1,491,000 | $502 | $1,911,200 |

| 2015 | 207 | 7,935 | 38 | 2,496 | $1,732,400 | $694 | $4,231,600 |

| 2016 | 235 | 6,079 | 26 | 3,572 | $1,546,500 | $433 | $2,368,500 |

| 2017 | 330 | 7,314 | 22 | 3,717 | $2,480,400 | $667 | $2,343,100 |

| 2018 | 318 | 8,438 | 27 | 4,328 | $2,007,500 | $464 | $3,119,900 |

| 2019 | 431 | 11,984 | 28 | 4,994 | $2,419,800 | $485 | $2,836,600 |

Note: Dollar amounts reported in this table have been adjusted for inflation to constant 2019 dollars using the CPI-U-RS. As a result, the dollar amounts presented here may differ from the amounts reported in the source data. Totals may not sum due to rounding.

Source: Authors’ analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, Agriculture data table (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020a).

Figure E is based on the same data as Table 2 and shows the fluctuation of back wages owed based on H-2A violations between fiscal years 2000 and 2019. There is no statistically significant trend in the amount of back wages owed to workers based on H-2A violations between fiscal years 2000 and 2019.9 H-2A workers are in the United States an average of six months, and they earn roughly $2,000 to $3,000 a month, or $12,000 to $18,000 during their average six months in the United States, so back wages of $485 (the average in FY2019) equal 3% to 4% of total earnings during their term of employment.

Average back wages assessed to workers per H-2A violation, fiscal years 2000–2019

| Fiscal year | Average back wages per employee |

|---|---|

| 2000 | $446 |

| 2001 | $570 |

| 2002 | $278 |

| 2003 | $537 |

| 2004 | $338 |

| 2005 | $503 |

| 2006 | $1,048 |

| 2007 | $298 |

| 2008 | $717 |

| 2009 | $322 |

| 2010 | $457 |

| 2011 | $599 |

| 2012 | $624 |

| 2013 | $1,101 |

| 2014 | $502 |

| 2015 | $694 |

| 2016 | $433 |

| 2017 | $667 |

| 2018 | $464 |

| 2019 | $485 |

Note: Dollar amounts reported in this figure have been adjusted for inflation to constant 2019 dollars using the CPI-U-RS. As a result, the dollar amounts presented here may differ from the amounts reported in the source data.

Source: Authors’ analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, Agriculture data table (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020a).

Violations of other employment laws

WHD enforces the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) and other employment laws, and WHD investigators found more than 114,000 violations of MSPA and H-2A rules on 9,330 farm establishments over the past two decades (see Table 3). Farm employers were ordered to pay nearly $42 million in back wages to 71,600 farmworkers, and they were assessed almost $6 million in civil money penalties. Violations of the FLSA are grouped together with other violations in the data, so we cannot distinguish them from other employment law violations.

Enforcement of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) and other employment laws: Back wages and civil monetary penalties assessed by the Wage and Hour Division resulting from FLSA and other violations, fiscal years 2000–2019

| Fiscal Year | Cases with violations | Total other violations (excluding OSHA) | Average violations per case | Employees receiving back wages | Back wages ($2019) | Average back wages per employee ($2019) | Civil monetary penalties assessed ($2019) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total or Average | 9,330 | 114,209 | 12 | 71,574 | $41,741,836 | $583 | $5,812,536 |

| 2000 | 490 | 5,594 | 11 | 3,405 | $1,686,714 | $495 | $469,463 |

| 2001 | 399 | 4,254 | 11 | 3,023 | $1,290,809 | $427 | $252,743 |

| 2002 | 437 | 4,917 | 11 | 3,234 | $2,046,841 | $633 | $219,876 |

| 2003 | 386 | 6,320 | 16 | 5,467 | $2,523,629 | $462 | $196,580 |

| 2004 | 401 | 3,733 | 9 | 2,383 | $1,094,632 | $459 | $498,793 |

| 2005 | 366 | 2,521 | 7 | 1,810 | $1,143,251 | $632 | $184,230 |

| 2006 | 351 | 2,944 | 8 | 1,895 | $1,675,186 | $884 | $106,720 |

| 2007 | 426 | 6,422 | 15 | 5,589 | $3,173,022 | $568 | $153,886 |

| 2008 | 396 | 3,032 | 8 | 2,372 | $1,390,051 | $586 | $121,955 |

| 2009 | 422 | 3,438 | 8 | 2,133 | $808,472 | $379 | $134,786 |

| 2010 | 406 | 12,166 | 30 | 6,424 | $2,890,384 | $450 | $83,953 |

| 2011 | 450 | 4,364 | 10 | 2,958 | $1,859,571 | $629 | $146,359 |

| 2012 | 531 | 6,300 | 12 | 4,743 | $3,023,412 | $637 | $235,441 |

| 2013 | 641 | 6,685 | 10 | 3,637 | $2,860,367 | $786 | $362,770 |

| 2014 | 608 | 5,838 | 10 | 4,309 | $2,574,113 | $597 | $382,899 |

| 2015 | 566 | 8,345 | 15 | 4,855 | $2,230,751 | $459 | $264,208 |

| 2016 | 580 | 11,226 | 19 | 5,316 | $2,890,541 | $544 | $336,169 |

| 2017 | 561 | 4,322 | 8 | 2,635 | $2,523,721 | $958 | $453,201 |

| 2018 | 477 | 5,049 | 11 | 2,491 | $1,704,014 | $684 | $704,590 |

| 2019 | 436 | 6,739 | 15 | 2,895 | $2,352,358 | $813 | $503,914 |

Note: Violations of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) are grouped together with other violations in the DOL data we utilized, except for MSPA and H-2A violations, therefore we cannot distinguish FLSA violations from other employment law violations (other than MSPA and H-2A, which are presented in Tables 1 and 2). Dollar amounts reported in this table have been adjusted for inflation to constant 2019 dollars using the CPI-U-RS. As a result, the dollar amounts presented here may differ from the amounts reported in the source data. Totals may not sum due to rounding.

Source: Authors’ analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, Agriculture data table (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020a).

Two decades of aggregate WHD data on farm labor enforcement reveal three major patterns

Our analysis of WHD’s aggregate data on enforcement from fiscal years 2000 and 2019 revealed three notable patterns.

First, as shown in Figure A, the number of WHD investigations in U.S. agriculture has fallen below 1,200 a year—to an average of less than 100 a month—in the last two years. Nevertheless, the data show that agriculture accounts for a much higher share of investigations and violations than its share of employment. The Census of Agriculture (COA) reported more than 500,000 farm employers in the United States in 2017 (Rural Migration News 2019), and 107,000 agricultural establishments were registered with state unemployment insurance agencies in 2019, according to the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) (BLS-QCEW 2020a). Average farmworker employment according to the QCEW was 1.3 million, about 1% of total U.S. employment in 2019. However, agriculture accounted for 7% of all federal wage and hour investigations and 3% of the 10 million federal wage and hour law violations found over the past 15 years—three times agriculture’s share of employment (BLS-QCEW 2020a; U.S. DOL-WHD 2020a).

Using the QCEW number of establishments as a reference for the number of agricultural employers, means the probability of any single farm ever being investigated for federal employment law violations in a given year is low: 1.1%. The QCEW number of agricultural establishments includes only those required to register and pay unemployment insurance taxes, and is thus only a fifth of the agricultural employers in the COA. Thus, our estimate of 1.1% likely overstates the likelihood that an agricultural employer will be investigated.

Second, violations of MSPA are found on almost half of the farms inspected, and the civil money penalties assessed for MSPA violations are more than twice the amount of back wages owed to farmworkers.

Third, the share of agricultural investigations that find violations of H-2A regulations is rising sharply. Between fiscal years 2000 and 2019, H-2A violations resulted in back wages owed that average $7,300 per farm with violations, and $9,400 per farm in CMP assessments.10 However, U.S. farmers pay about $40 billion a year in wages to farmworkers (USDA 2017). Given that total wage bill, the $6 million in back wages and $6.3 million in CMPs that employers were required to pay In fiscal 2019 (see Figure C) were a miniscule share of the annual overall wage bill.

A note about the data

Figures A, C, and E, and Tables 1–3 in the preceding section are generated from summary statistics on the WHD website that include a warning: “Wage and Hour investigations, including those in agriculture, often involved the concurrent enforcement of multiple statutes. Therefore, duplication may exist in the data” (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020a). The analysis in the following sections is based on a separate WHD enforcement database that “contains all concluded WHD compliance actions since FY 2005” (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f). There are differences between the summary statistics data and the enforcement database, so there may be discrepancies between the summary analysis and the detailed analysis that follows.

Fifteen years of detailed data on the outcomes of farm labor investigations

This section draws on the analysis of a WHD database that summarizes the outcomes of more than 294,000 investigations between fiscal years 2005 and 2019 in both the public and private sectors (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f). Entries for each investigation include the employer’s contact information, NAICS industry code, and details of the investigation, such as the number of violations found, how many workers were affected, what back wages were owed, and the civil money penalties assessed on employers.

Federal farm labor investigations between fiscal years 2005 and 2019

The 294,000 investigations over 15 years in all U.S. industries found more than 10 million violations. About 5% of all violations in the database, 530,000, were found at a single Wells Fargo Bank branch in Roseville, Minnesota, in 2012–2013.

Some 19,250 WHD investigations between fiscal years 2005 and 2019, about 6.5% of all investigations, had an agricultural NAICS industry code associated with them, from 1111 for Oilseed and Grain Farming to 115310 for Support Activities for Forestry. More than 10% of the 17,000 farming operations that were investigated were visited multiple times. These agricultural investigations detected a total of 229,000 violations of the three major federal labor standards laws or regulations that apply on farms: the FLSA (22% of all violations), MSPA (30%), and H-2A program rules (33%).

Figure F shows the number of MSPA, H-2A, and FLSA violations in agriculture detected by WHD from fiscal years 2005 to 2019, and finds the number of detected violations of all three laws peaked during fiscal years 2011, 2012, or 2013. The number of detected violations in all three categories reached a record low in fiscal 2019, declining as the number of investigations in agriculture declined.

In 2019, the number of employment law violations detected by the Wage and Hour Division (WHD) among agricultural employers dropped to the lowest point in 15 years: Number of MSPA, H-2A, and FLSA violations detected by WHD investigations in agriculture, fiscal years 2005–2019

| Fiscal year | MSPA violations | H-2A violations | FLSA violations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 3,933 | 1,782 | 2,029 |

| 2006 | 4,336 | 4,587 | 5,708 |

| 2007 | 4,790 | 7,604 | 2,463 |

| 2008 | 4,380 | 7,853 | 3,440 |

| 2009 | 6,421 | 7,116 | 2,508 |

| 2010 | 5,115 | 7,349 | 6,637 |

| 2011 | 7,085 | 11,856 | 4,449 |

| 2012 | 11,551 | 7,277 | 7,882 |

| 2013 | 12,700 | 3,940 | 7,816 |

| 2014 | 6,521 | 7,738 | 5,799 |

| 2015 | 4,920 | 5,995 | 4,497 |

| 2016 | 3,256 | 4,479 | 1,532 |

| 2017 | 2,659 | 6,280 | 1,862 |

| 2018 | 2,545 | 4,196 | 1,451 |

| 2019 | 659 | 1,636 | 708 |

Note: MSPA stands for the Migrant and Seasonal Worker Protection Act, H-2A is the H-2A work visa program for temporary agricultural workers, and FLSA stands for the Fair Labor Standards Act.

Source: Authors' analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Compliance Action Data (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f).

Figure G groups the number of violations found per investigation during the FY2005–FY2019 period, from zero to more than five violations per investigation. When looked at this way, the data reveal a U-shape among the violators, with almost 30% of investigations bunched at the zero and 31% bunched at more than five violations; those two ends of the spectrum account for almost two-thirds of the violations, while 17% of investigations found one violation and 23%, nearly a quarter, found two to four violations. However, overall, the data show that 70% of all investigations detected violations, while 30% detected zero violations. In addition, it should be noted that this figure does not account for the severity of the violations or the amounts assessed. In other words, some investigations that detected one or two violations may have detected egregious violations and found employers owing large amounts of back pay, while investigations that detected with five or more violations may have resulted in smaller amounts of back wages owed.

Over 70% of federal investigations of agricultural employers detected wage and hour violations: Violations detected during investigations of agricultural employers, by number of violations found per investigation, fiscal years 2005–2019

| Number of violations | Share of investigations |

|---|---|

| 0 violations | 29.5% |

| 1 violation | 16.7% |

| 2–4 violations | 22.7% |

| 5+ violations | 31.1% |

Note: Data include H-2A, MSPA, FLSA, and all other types of employment law violations in the agricultural sector.

Source: Authors' analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Compliance Action Data (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f).

We reviewed the average number of violations per investigation by state. Figure H shows that the highest number of average violations detected per investigation were not in the five states with the most farm employment. In other words, the WHD investigations that detected the most violations per investigation were not always in the states with the most farmworker employment. It stands to reason that the distribution of violations may be related to the distribution of resources among regional WHD offices, and/or it may be related to differing approaches and priorities among regional WHD offices.

Average number of employment law violations detected by the Wage and Hour Division per investigation that discovered violations among agricultural employers, by state, fiscal years 2005–2019

| State | Average violations per investigation |

|---|---|

| Alabama | 11.6 |

| Alaska | NA |

| Arizona | 55.9 |

| Arkansas | 28.1 |

| California | 24.7 |

| Colorado | 24.0 |

| Connecticut | 14.2 |

| Delaware | 5.3 |

| Washington D.C. | NA |

| Florida | 15.3 |

| Georgia | 21.4 |

| Hawaii | NA |

| Idaho | 55.7 |

| Illinois | 15.7 |

| Indiana | 5.9 |

| Iowa | 67.1 |

| Kansas | 23.5 |

| Kentucky | 17.1 |

| Louisiana | 23.1 |

| Maine | 13.2 |

| Maryland | 9.6 |

| Massachusetts | 14.6 |

| Michigan | 14.9 |

| Minnesota | 24.6 |

| Mississippi | 24.8 |

| Missouri | 68.1 |

| Montana | 10.5 |

| Nebraska | 24.8 |

| Nevada | 65.3 |

| New Hampshire | 12.7 |

| New Jersey | 13.2 |

| New Mexico | 8.8 |

| New York | 13.1 |

| North Carolina | 46.2 |

| North Dakota | 10.4 |

| Ohio | 11.6 |

| Oklahoma | 12.3 |

| Oregon | 51.3 |

| Pennsylvania | 9.7 |

| Rhode Island | 4.1 |

| South Carolina | 8.9 |

| South Dakota | 19.0 |

| Tennessee | 18.2 |

| Texas | 9.7 |

| Utah | 32.9 |

| Vermont | 8.3 |

| Virginia | 15.0 |

| Washington | 42.7 |

| West Virginia | 14.2 |

| Wisconsin | 9.2 |

| Wyoming | 14.6 |

Note: Major farm employment states are California, Texas, Florida, Washington, and North Carolina. Data include H-2A, MSPA, FLSA, and all other types of employment law violations in the agricultural sector.

Source: Authors' analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Compliance Action Data (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f).

Farm labor contractors between fiscal years 2005 and 2019

Farm labor contractors (FLCs) are nonfarm employers that act as staffing firms for farm employers. For FLCs, which correspond to NAICS code 115115, average employment was 181,000 in 2019, according to the QCEW (BLS-QCEW 2020a); FLCs are a subset of the Support Activities for Crop Production category (NAICS 1151), which had average employment of 342,000, meaning that FLCs accounted for 53% of U.S. crop support services employment.

FLCs accounted for 14% of total average employment in UI-covered agriculture of 1.3 million in 201911—including employment in both crops and animal agriculture—but accounted for one-quarter of all employment law violations detected in agriculture (24%). Thus, the share of agricultural employment law violations committed by farm labor contractors was 10 percentage points greater than the FLC share of average annual agricultural employment. In practical terms, that means that farmworkers employed by FLCs or on farms that use FLCs are more likely to suffer wage and hour violations than farmworkers who are employed by farms directly.

We found that 75% of all WHD investigations of FLCs detected violations, while 25% of investigations detected zero violations. We grouped the number of violations detected per investigation of FLCs, as shown in Figure I. The share of investigations of FLCs that found zero violations, at 25%, was significantly less than the share of investigations of FLCs that found five or more violations, 36%. Nearly two-fifths of investigations detected either one violation or two to four violations.

We reviewed the average number of violations detected by investigations of FLCs by state. Figure J shows that when violations committed by FLCs are found as the result of an investigation, the highest number of average violations per investigation were not in the five states with the most agricultural employment.

Three-fourths of federal investigations of farm labor contractors detected wage and hour violations: Violations detected during investigations of farm labor contractors, by number of violations found per investigation, fiscal years 2005–2019

| Number of violations | Share of investigations |

|---|---|

| 0 Violations | 25.3% |

| 1 Violation | 15.9% |

| 2–4 Violations | 22.9% |

| 5+ Violations | 35.9% |

Source: Authors' analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Compliance Action Data (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f).

Average number of employment law violations detected by the Wage and Hour Division per investigation that discovered violations among farm labor contractors, by state, fiscal years 2005–2019

| State | Average farm labor contractor violations per investigation |

|---|---|

| Alabama | 46.0 |

| Alaska | NA |

| Arizona | 67.8 |

| Arkansas | 31.1 |

| California | 25.9 |

| Colorado | 43.0 |

| Connecticut | 2.0 |

| Delaware | NA |

| Washington D.C. | NA |

| Florida | 16.2 |

| Georgia | 19.3 |

| Hawaii | NA |

| Idaho | 24.1 |

| Illinois | 3.0 |

| Indiana | 11.6 |

| Iowa | 167.0 |

| Kansas | 25.2 |

| Kentucky | 5.8 |

| Louisiana | 3.7 |

| Maine | 10.5 |

| Maryland | 3.0 |

| Massachusetts | 2.0 |

| Michigan | 9.7 |

| Minnesota | 8.0 |

| Mississippi | 10.2 |

| Missouri | 10.0 |

| Montana | NA |

| Nebraska | 29.9 |

| Nevada | NA |

| New Hampshire | NA |

| New Jersey | 11.3 |

| New Mexico | 4.7 |

| New York | 2.1 |

| North Carolina | 8.5 |

| North Dakota | NA |

| Ohio | 3.7 |

| Oklahoma | 8.6 |

| Oregon | 59.7 |

| Pennsylvania | 29.4 |

| Rhode Island | NA |

| South Carolina | 9.3 |

| South Dakota | 22.0 |

| Tennessee | 13.2 |

| Texas | 8.1 |

| Utah | NA |

| Vermont | NA |

| Virginia | 2.3 |

| Washington | 47.6 |

| West Virginia | NA |

| Wisconsin | 3.0 |

| Wyoming | NA |

Note: Major farm employment states are California, Texas, Florida, Washington, and North Carolina.

Source: Authors' analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Compliance Action Data (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f).

FLCs bring workers to farms, but we do not have data on the commodities grown on the farms where FLC employees work. We know that most FLC employees work on fruit and vegetable farms, since these commodities require the most seasonal workers that FLCs specialize in providing. For this reason, we cannot directly compare FLC violations with violations committed by crop farms, or citrus farms, because crop and citrus farms both may hire workers directly and use FLCs to obtain workers.

However, if we consider FLCs as a unique NAICS code (115115) and compare the FLC code to others, then FLCs top the list when it comes to federal wage and hour violations, followed by Vegetable and Melon Farming (NAICS 1112) employers, at about 15% of all agricultural violations, and where average employment of 93,000 was 7% of the 1.3 million total UI-covered agricultural employment in 2019. Ten percent of violations were in Poultry and Egg Production (1123), almost all associated with a single employer, Perdue Foods. Four six-digit NAICS industries each accounted for 4% of all employment law violations: Berry (except Strawberry) Farming (111334); Apple Orchards (111331); All Other Miscellaneous Crop Farming (111998); and Broilers and Other Meat Type Chicken Production (11232).

Violations by state and county between fiscal years 2005 and 2019

Agricultural employment is concentrated on farms that produce labor-intensive commodities in a handful of states, and in particular, counties within these states. For example, the five states with the highest agricultural employment include more than half of all farm jobs, and the five leading farm counties in California include more than half of the state’s farm jobs. In this section, we examine how employment law violations in agriculture are distributed by state and by county, and take a closer look at Florida and California, and particular counties in California. We also highlight the commodities (by NAICS codes) where federal wage and hour laws are most likely to be violated.

California and Florida had the most violations, and the biggest violators are FLCs

California and Florida each accounted for 14% of the employment law violations detected as the result of WHD investigations nationwide, followed by North Carolina with 10% (due in large part to Perdue Farms), Texas and Washington with 5% each, and Oregon with 4%. These six states accounted for 52% of all employment law violations found in agriculture. In the two states with the highest shares of violations, FLCs accounted for the largest share of the violations detected by WHD investigators. Figure K shows that FLCs accounted for 48% of the total violations in California during fiscal years 2005 to 2019, and Figure L shows that FLCs accounted for 50% of the total violations detected in Florida over the same period.

Employer violations detected in California by the Wage and Hour Division among all agricultural employers and farm labor contractors, fiscal years 2005–2019

| Year | Violations by all agricultural employers | Violations by farm labor contractors |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 1,233 | 972 |

| 2006 | 4,166 | 918 |

| 2007 | 1,931 | 1,189 |

| 2008 | 2,911 | 1,469 |

| 2009 | 2,202 | 1,645 |

| 2010 | 1,577 | 363 |

| 2011 | 2,909 | 1,949 |

| 2012 | 4,589 | 1,556 |

| 2013 | 5,420 | 3,348 |

| 2014 | 3,079 | 1,302 |

| 2015 | 2,181 | 947 |

| 2016 | 2,113 | 1,490 |

| 2017 | 1,902 | 570 |

| 2018 | 2,794 | 733 |

| 2019 | 315 | 240 |

Note: Violations by California farm labor contractor are a subset of employment law violations detected among all agricultural employers in California.

Source: Authors' analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Compliance Action Data (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f).

Employer violations detected in Florida by the Wage and Hour Division among all agricultural employers and farm labor contractors, fiscal years 2005–2019

| Year | Violations by all agricultural employers | Violations by farm labor contractors |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 1,225 | 670 |

| 2006 | 1,484 | 686 |

| 2007 | 4,469 | 1,643 |

| 2008 | 1,989 | 1,021 |

| 2009 | 2,034 | 1,020 |

| 2010 | 2,886 | 545 |

| 2011 | 4,045 | 1,726 |

| 2012 | 4,633 | 2,765 |

| 2013 | 2,380 | 1,084 |

| 2014 | 3,744 | 1,986 |

| 2015 | 3,338 | 2,360 |

| 2016 | 1,871 | 1,182 |

| 2017 | 1,837 | 974 |

| 2018 | 1,412 | 1,112 |

| 2019 | 989 | 455 |

Note: Violations by Florida farm labor contractor are a subset of employment law violations detected among all agricultural employers in Florida..

Source: Authors' analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Compliance Action Data (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f).

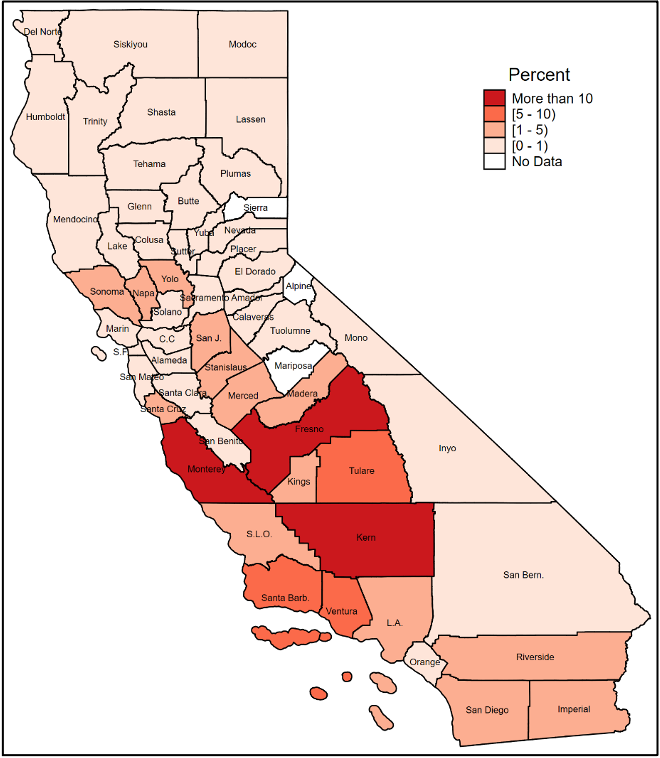

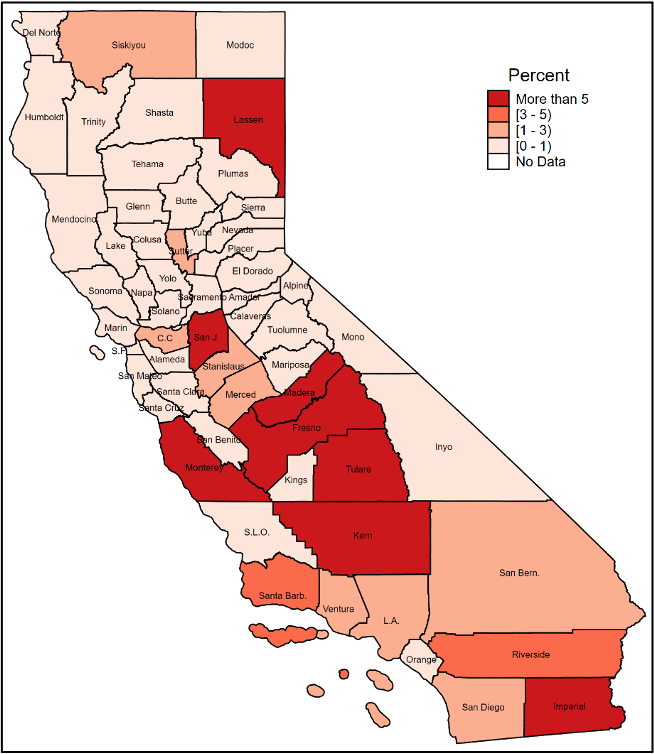

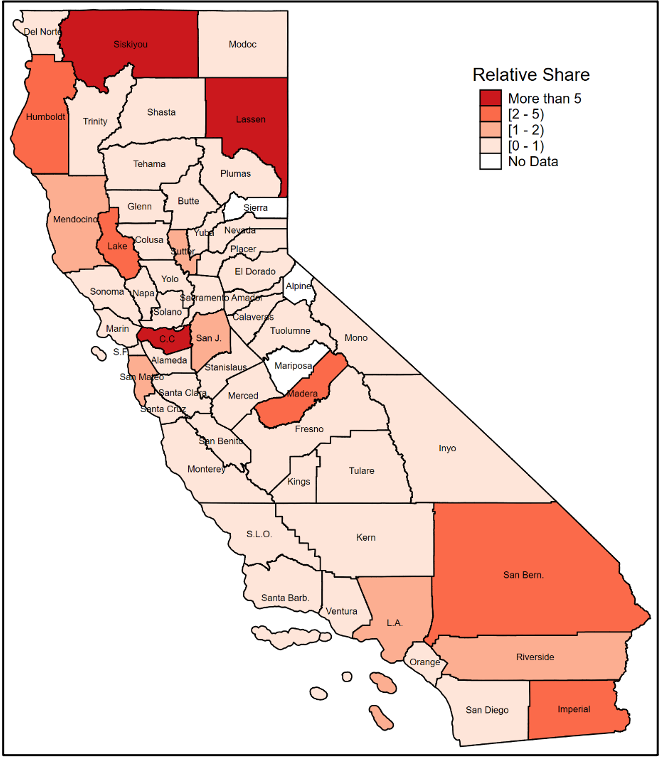

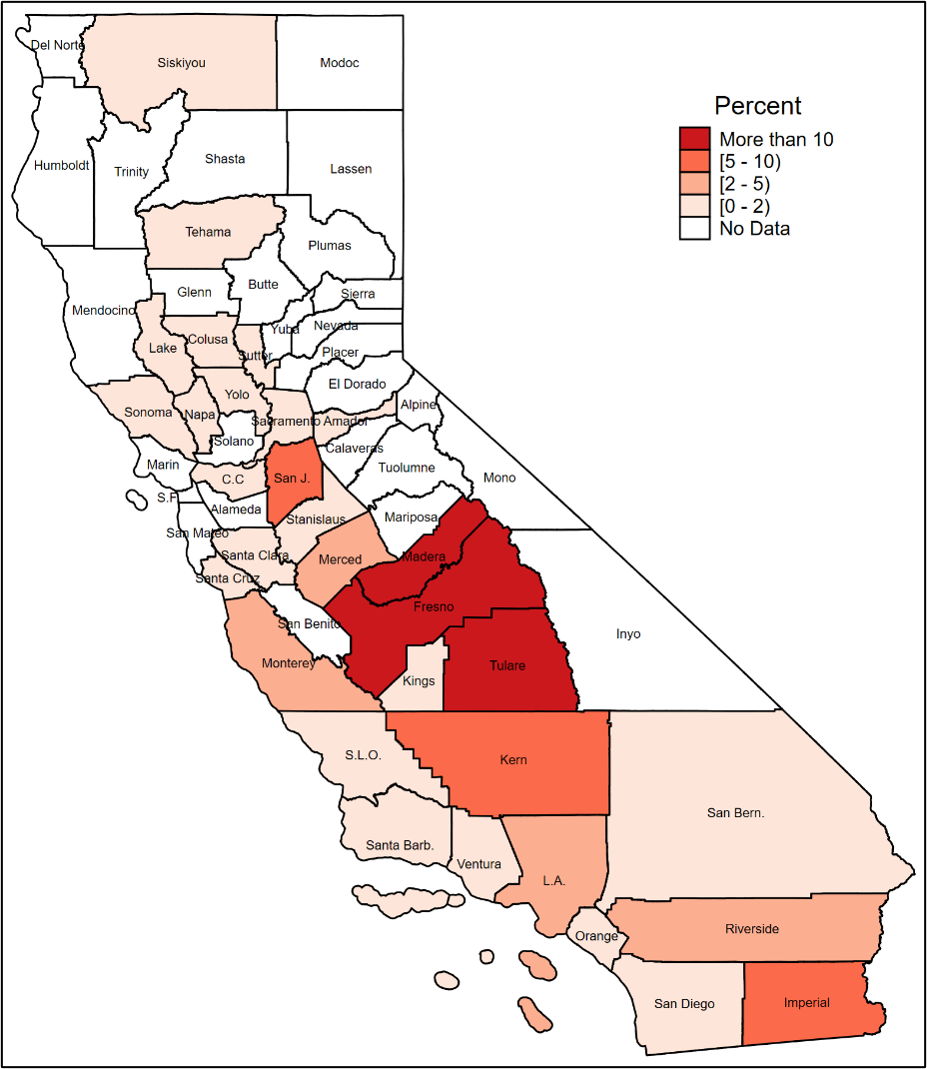

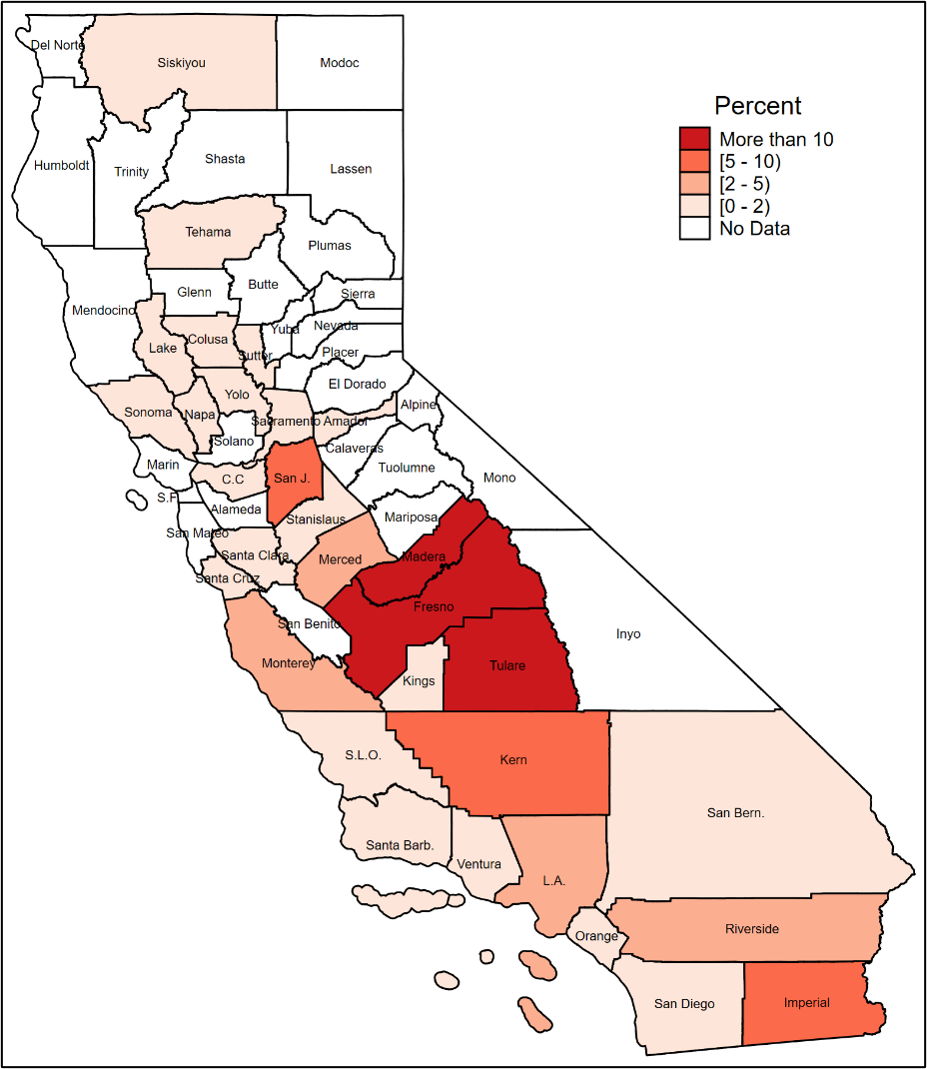

Figures M1–M3 compare each California county’s share of agricultural employment and its share of employment law violations detected by WHD. Counties with a small share of agricultural employment can have a larger share of employment law violations—in other words, the correlation between the two is far from perfect. For example, Siskiyou and Lassen counties have a far higher share of the employment law violations than their shares of agricultural employment, while the major farm employment counties of Fresno, Kern, and Tulare have a smaller share of violations than their shares of agricultural employment.

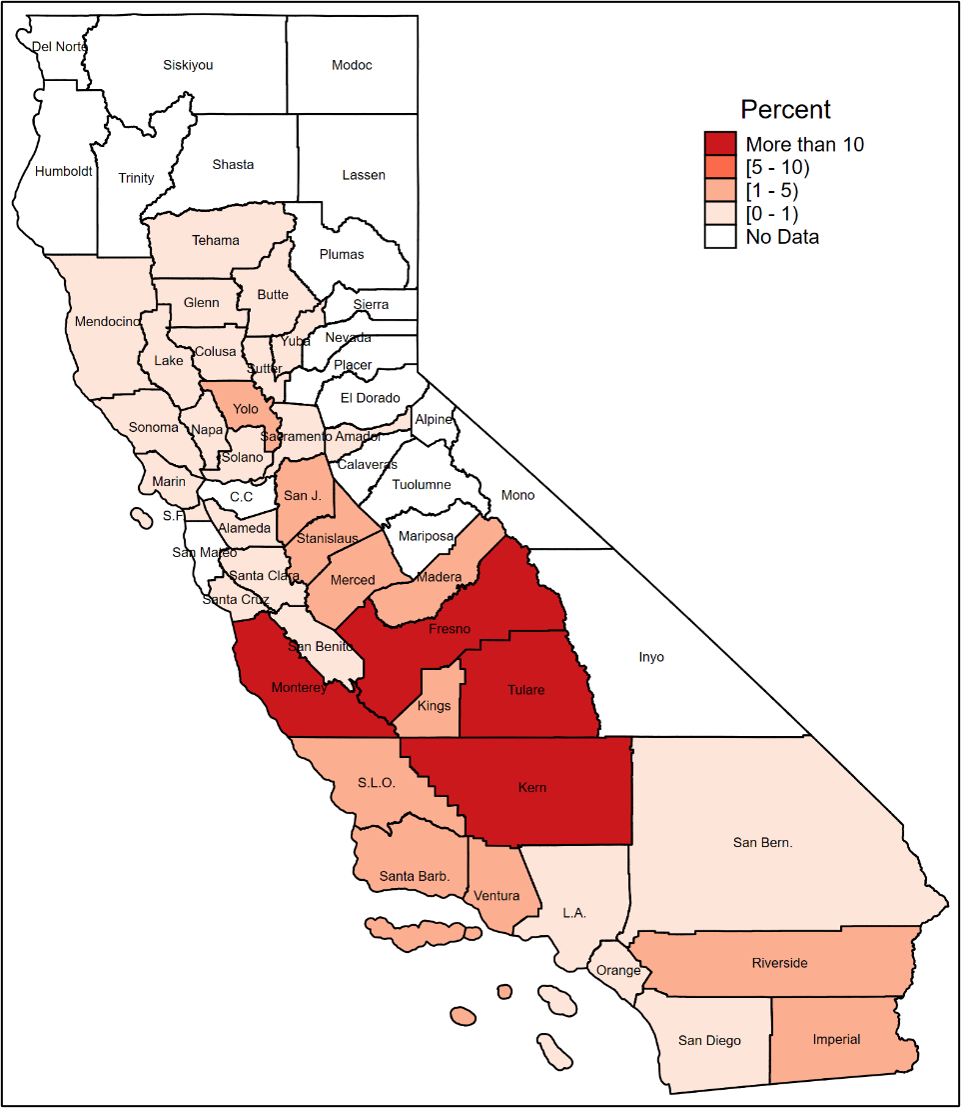

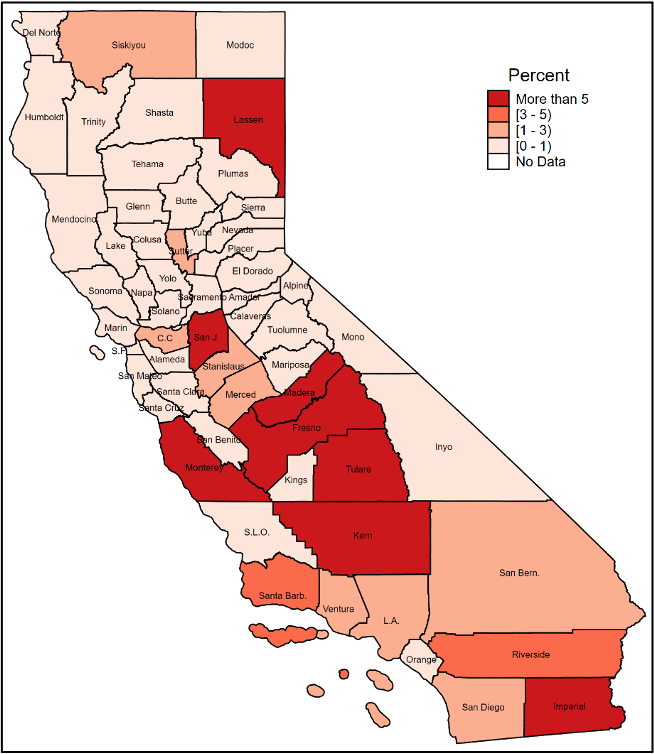

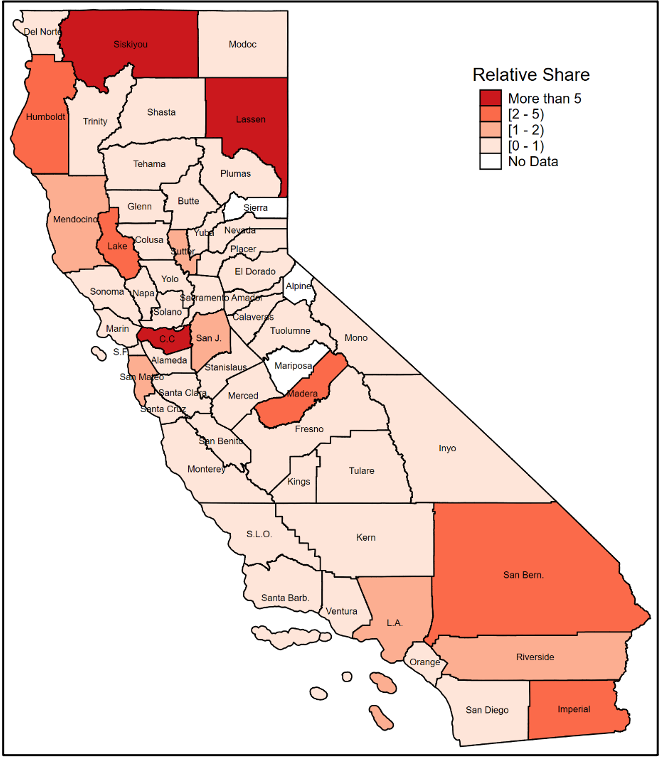

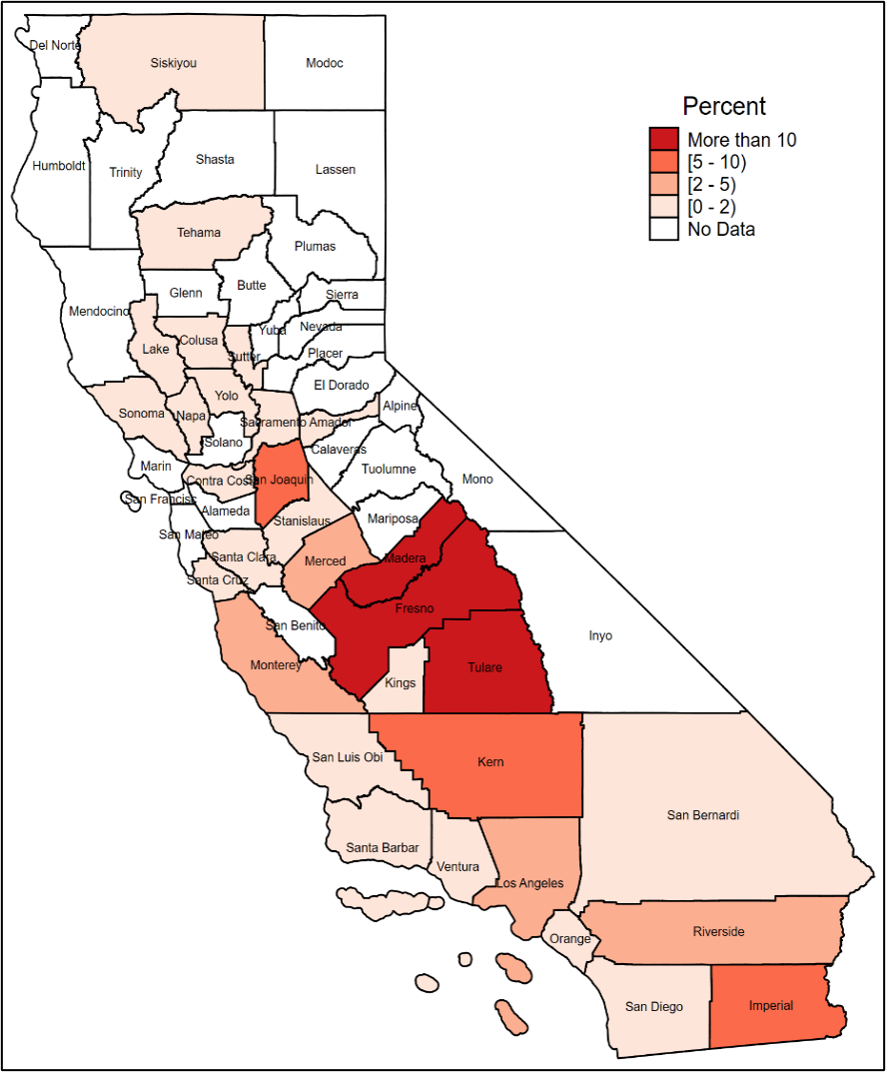

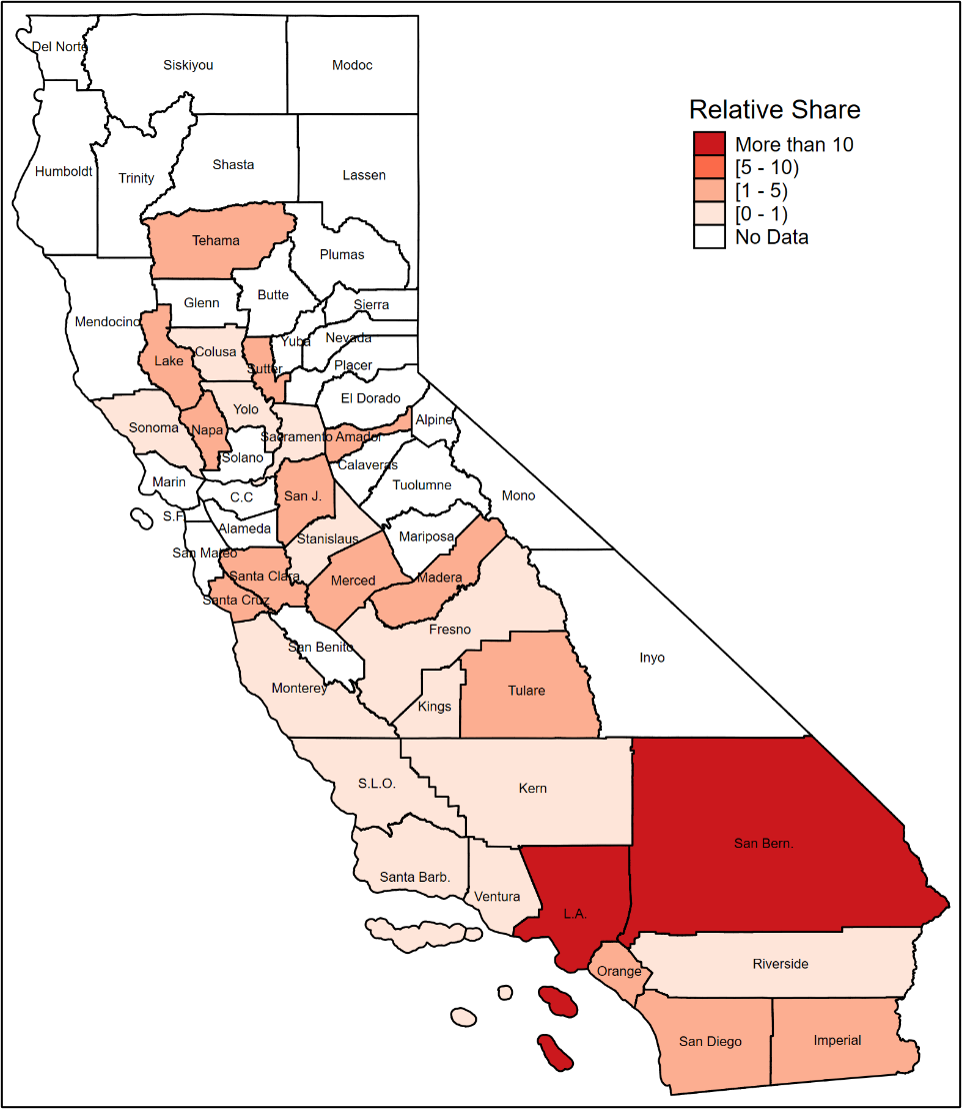

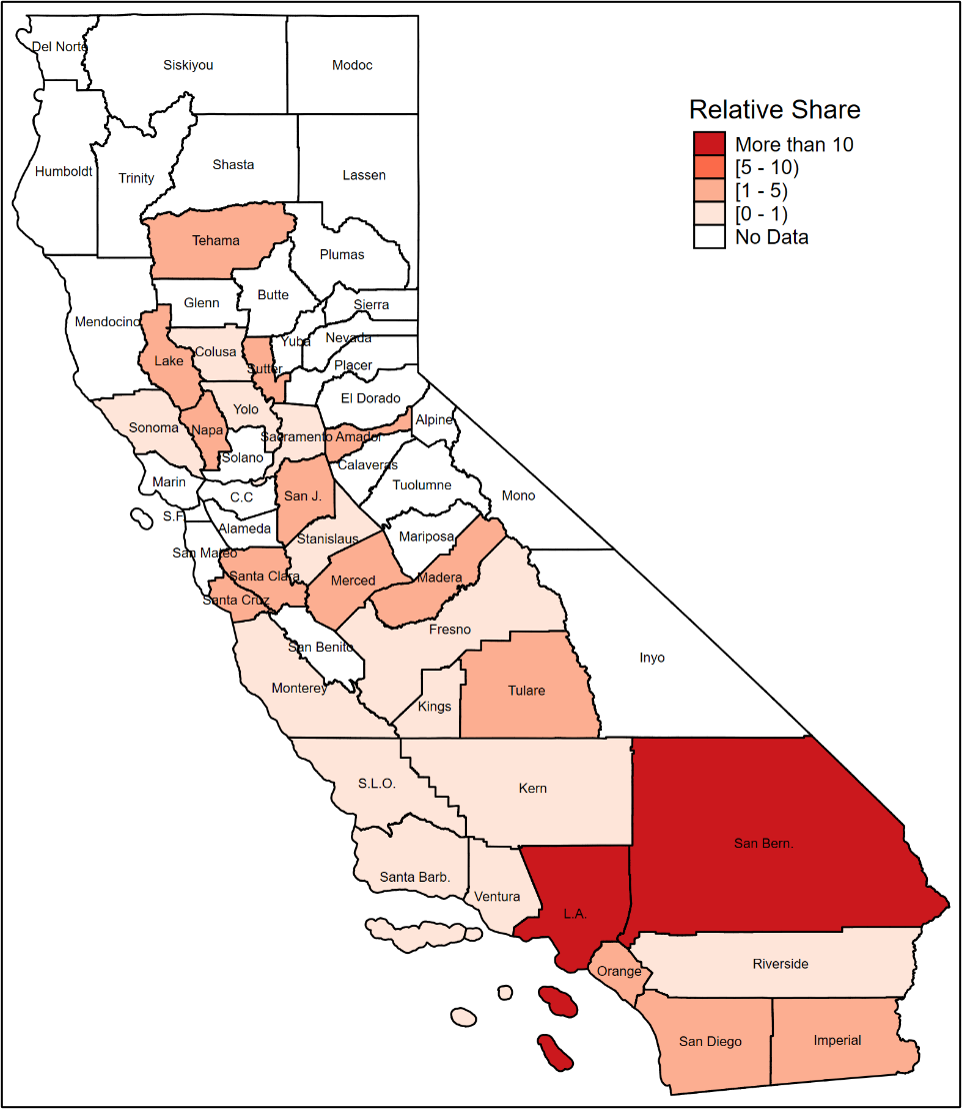

Comparing each county’s share of FLC violations with its share of FLC employment tells a similar story. FLC employment is concentrated in the state’s major farm employment counties of Kern, Tulare, Fresno, and Monterey, and these counties also have a high share of all employment law violations committed by FLCs. However, Figures N1–N3 show that, with the exception of Tulare County, the share of FLC violations in leading farm counties is lower than their share of FLC employment, but counties such as Los Angeles and San Bernardino, with relatively small shares of FLC employment, had higher shares of FLC violations. A handful of other counties, scattered primarily throughout the Central Valley, also had a larger share of FLC violations relative to their share of FLC employment.

Percent of total federal employment law violations detected by the Wage and Hour Division among agricultural employers in California, by county, fiscal years 2005–2019

Note: The county-level data in this figure were constructed from data that identifies the Zip code where the employer was located. Some California Zip codes cross county boundaries and, as a result, some investigations could not be assigned to a county.

Source: Authors' analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Compliance Action Data (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f).

Ratio of California county share of federal employment law violations detected by the Wage and Hour Division among agricultural employers to the share of agricultural employment in the county, fiscal years 2005–2019

Note: The figure depicts the ratio of each county's share of farm labor violations that were detected between fiscal years 2005 and 2019 relative to the county’s share of agricultural employment. Values less than 1 indicate that a county has a smaller share of violations compared to its share of employment. Larger values indicate that the agricultural employers who were investigated within a county were generally less compliant with employment laws.

Source: Authors' analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Compliance Action Data (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f) and Bureau of Labor Statistics, Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages data for North American Industry Classification System code 11, agriculture, in 2018 (BLS-QCEW 2020a).

Percent of total federal employment law violations detected by the Wage and Hour Division among farm labor contractors in California, by county, fiscal years 2005–2019

Note: The county-level data in this figure were constructed from data that identifies the Zip code where the employer was located. Some California Zip codes cross county boundaries and, as a result, some investigations could not be assigned to a county.

Source: Authors' analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Compliance Action Data (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f).

Ratio of California county share of federal employment law violations detected by the Wage and Hour Division among farm labor contractors to the share of agricultural employment in the county, fiscal years 2005–2019

Note: The figure depicts the ratio of each county's share of farm labor violations that were detected among FLCs between fiscal years 2005 and 2019 relative to each county's share of FLC employment in 2018. Values less than 1 indicate that a county has a smaller share of violations compared to its share of employment. Larger values indicate that the FLCs who were investigated within a county were generally less compliant with employment laws. Mountainous counties in the north and east of California have few or no FLCs.

Source: Authors' analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Compliance Action Data (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f) and Bureau of Labor Statistics, Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages data for North American Industry Classification System code 11, agriculture, in 2018 (BLS-QCEW 2020a).

Probability of finding violations in California agriculture

During the Obama administration and under the leadership of WHD Administrator David Weil, the WHD developed a more strategic approach to labor standards enforcement, emphasizing investigations in industries and areas where there were likely to be employment law violations. We used the enforcement data to examine the probability that violations would be found among employers of particular commodities in California, as reflected in their NAICS codes.

Table 4 shows the probability that a violation is detected during an investigation by commodity or NAICS category.12 FLCs are not a commodity because they supply farmworkers to employers who grow many commodities, but they are included for comparison purposes. The highest probability of finding a violation is 72% for fruit and tree nut farming, followed by 64% for vegetable and melon farming investigated. More than half of greenhouse, nursery, and floriculture operations that were investigated, and more than half of animal production and aquaculture that were investigated, had one or more employment law violations.13 In the case of FLCs, almost 85% of California FLCs that were investigated had at least one employment law violation, as did 72% of other crop support service employers that were investigated (excluding FLCs). In sum, most agricultural investigations find violations, and farms that utilize FLCs are where the probability of finding violations is the highest. (If the violations committed by FLCs were categorized under their corresponding commodities, an even higher share of fruit and vegetable farms would have had violations.)

We calculated the probability that an investigation would find at least one violation in the top 10 agricultural counties in California.14 Table 5 shows that more than half of all agricultural investigations in each of these California counties found violations, ranging from roughly 60% of investigations in Imperial and Ventura counties to 80% or 90% in Fresno and Tulare counties.

Probability that federal employment law violations will be detected during an investigation by the Wage and Hour Division in California, by commodity or type of employment, fiscal year 2005–2019

| Commodity or type of employment | Probability of finding a violation |

|---|---|

| Vegetable and melon farming | 0.641*** |

| (0.029) | |

| Fruit and tree nut farming | 0.719*** |

| (0.018) | |

| Greenhouse, nursery, and floriculture production | 0.533*** |

| (0.065) | |

| Other crops | 0.644*** |

| (0.047) | |

| Animal production and aquaculture | 0.545*** |

| (0.067) | |

| Support activities for crop production (non-FLC) | 0.718*** |

| (0.035) | |

| Farm Labor Contractors | 0.845*** |

| (0.012) | |

| Number of violations | 2,132 |

Note: Heteroskedastic-robust are standard errors in parentheses. * p < .1, ** p < .05, *** p < .01. A p-value of less than .01 indicates that there is less than a 1% chance of falsely rejecting the null hypothesis that a coefficient is equal to zero. In other words, if p < .01, it is highly unlikely that the true share of employers within a North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code that are guilty of at least one violation is equal to zero. Commodity and type of employment reflect corresponding NAICS codes associated with violations, or a combination of codes listed here: Vegetables and melon farming (1112); Fruit, tree, and nut farming (1113); Greenhouse, nursery, and floriculture production (1114); Animal production and aquaculture (112); Support activities for crop production (non-FLC) (1151 excluding 115115); and Other crops (1119, 1131, 11199, 111199, 111940, 111991, 111998). Non-FLC crop support services include cotton ginning, soil preparation, crop harvesting by machine, other post-harvest activities, and farm management services.

Source: Authors' analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Compliance Action Data (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f).

Probability that federal employment law violations will be detected during an investigation by the Wage and Hour Division in California, by county, fiscal years 2005–2019

| California county | Probability of finding a violation |

|---|---|

| Fresno | 0.835*** |

| (0.025) | |

| Imperial | 0.614*** |

| (0.049) | |

| Kern | 0.766*** |

| (0.035) | |

| Monterey | 0.741*** |

| (0.038) | |

| Riverside | 0.623*** |

| (0.041) | |

| San Diego | 0.705*** |

| (0.069) | |

| San Joaquin | 0.635*** |

| (0.036) | |

| Santa Barbara | 0.788*** |

| (0.071) | |

| Tulare | 0.899*** |

| (0.026) | |

| Ventura | 0.581*** |

| (0.053) | |

| Number of violations | 1,222 |

Note: Heteroskedastic-robust are standard errors in parentheses. * p < .1, ** p < .05, *** p < .01. A p-value of less than .01 indicates that there is less than a 1% chance of falsely rejecting the null hypothesis that a coefficient is equal to zero. In other words, if p < .01, it is highly unlikely that the true share of employers within a county that are guilty of at least one violation is equal to zero. Non-FLC crop support services include cotton ginning, soil preparation, crop harvesting by machine, other post-harvest activities, and farm management services.

Source: Authors' analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Compliance Action Data (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f).

Investigations and fines of repeat violators

One useful metric to determine whether WHD’s enforcement efforts are succeeding in educating and encouraging employers to follow the law is the degree to which individual employers continue to violate the law or come into compliance after repeat investigations. The WHD data allow us to track violations and fine amounts over time for employers that were investigated multiple times.

Our analysis of these data does not find any consistent compliance patterns for individual employers in terms of back wages owed per employee after repeat investigations. For example, some farm employers were investigated multiple times and never found to owe back wages, while others owed back wages in 75% or more of investigations. However, none of the employers investigated more than five times owed back wages after each investigation.

To illustrate this lack of a pattern, we show several agricultural employers in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas that were investigated more than 50 times between fiscal years 2005 and 2019. Figure O shows that J&D Produce (Little Bear) was investigated nearly 120 times, with two investigations finding average back wages owed to each affected employee of $46 and $113. Figure P shows that Frontera Produce was investigated more than 50 times and was assessed back wages of $471 per affected employee in only one investigation. Figure Q shows that Rio Fresh was investigated more than 60 times, and four times was found to owe back wages of $72, $28, $45, and $54 per affected employee—rather small amounts.

No consistent pattern of compliance for repeat violators: J&D Produce in Texas was investigated over 100 times during fiscal years 2005–2019

| Investigation number | Avg back wages per employee |

|---|---|

| 1 | $0 |

| 2 | $0 |

| 3 | $0 |

| 4 | $0 |

| 5 | $0 |

| 6 | $0 |

| 7 | $0 |

| 8 | $0 |

| 9 | $0 |

| 10 | $0 |

| 11 | $0 |

| 12 | $0 |

| 13 | $0 |

| 14 | $0 |

| 15 | $0 |

| 16 | $0 |

| 17 | $0 |

| 18 | $0 |

| 19 | $0 |

| 20 | $0 |

| 21 | $0 |

| 22 | $0 |

| 23 | $0 |

| 24 | $0 |

| 25 | $0 |

| 26 | $0 |

| 27 | $0 |

| 28 | $0 |

| 29 | $0 |

| 30 | $0 |

| 31 | $0 |

| 32 | $0 |

| 33 | $0 |

| 34 | $0 |

| 35 | $0 |

| 36 | $0 |

| 37 | $0 |

| 38 | $0 |

| 39 | $46 |

| 40 | $0 |

| 41 | $0 |

| 42 | $0 |

| 43 | $0 |

| 44 | $0 |

| 45 | $0 |

| 46 | $0 |

| 47 | $0 |

| 48 | $0 |

| 49 | $0 |

| 50 | $0 |

| 51 | $0 |

| 52 | $0 |

| 53 | $0 |

| 54 | $0 |

| 55 | $0 |

| 56 | $0 |

| 57 | $0 |

| 58 | $0 |

| 59 | $0 |

| 60 | $0 |

| 61 | $0 |

| 62 | $0 |

| 63 | $0 |

| 64 | $0 |

| 65 | $0 |

| 66 | $0 |

| 67 | $0 |

| 68 | $0 |

| 69 | $0 |

| 70 | $0 |

| 71 | $0 |

| 72 | $0 |

| 73 | $0 |

| 74 | $0 |

| 75 | $0 |

| 76 | $0 |

| 77 | $0 |

| 78 | $0 |

| 79 | $0 |

| 80 | $0 |

| 81 | $0 |

| 82 | $0 |

| 83 | $0 |

| 84 | $0 |

| 85 | $0 |

| 86 | $0 |

| 87 | $0 |

| 88 | $0 |

| 89 | $0 |

| 90 | $0 |

| 91 | $0 |

| 92 | $0 |

| 93 | $0 |

| 94 | $0 |

| 95 | $0 |

| 96 | $0 |

| 97 | $0 |

| 98 | $0 |

| 99 | $0 |

| 100 | $0 |

| 101 | $0 |

| 102 | $0 |

| 103 | $0 |

| 104 | $0 |

| 105 | $0 |

| 106 | $0 |

| 107 | $0 |

| 108 | $0 |

| 109 | $113 |

| 110 | $0 |

| 111 | $0 |

| 112 | $0 |

| 113 | $0 |

| 114 | $0 |

| 115 | $0 |

| 116 | $0 |

Note: Dollar amounts are adjusted for inflation to constant 2019 dollars using the CPI-U-RS. Number of Wage and Hour Division investigations and average back wages per employee owed for this employer between FY05 and FY19.

Source: Authors' analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Compliance Action Data (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f).

No consistent pattern of compliance for repeat violators: Frontera Produce in Texas was investigated over 50 times during fiscal years 2005–2019

| Investigation number | Avg back wages per employee |

|---|---|

| 1 | $0 |

| 2 | $0 |

| 3 | $0 |

| 4 | $0 |

| 5 | $0 |

| 6 | $0 |

| 7 | $0 |

| 8 | $0 |

| 9 | $0 |

| 10 | $0 |

| 11 | $0 |

| 12 | $0 |

| 13 | $0 |

| 14 | $0 |

| 15 | $0 |

| 16 | $0 |

| 17 | $0 |

| 18 | $0 |

| 19 | $471 |

| 20 | $0 |

| 21 | $0 |

| 22 | $0 |

| 23 | $0 |

| 24 | $0 |

| 25 | $0 |

| 26 | $0 |

| 27 | $0 |

| 28 | $0 |

| 29 | $0 |

| 30 | $0 |

| 31 | $0 |

| 32 | $0 |

| 33 | $0 |

| 34 | $0 |

| 35 | $0 |

| 36 | $0 |

| 37 | $0 |

| 38 | $0 |

| 39 | $0 |

| 40 | $0 |

| 41 | $0 |

| 42 | $0 |

| 43 | $0 |

| 44 | $0 |

| 45 | $0 |

| 46 | $0 |

| 47 | $0 |

| 48 | $0 |

| 49 | $0 |

| 50 | $0 |

| 51 | $0 |

| 52 | $0 |

| 53 | $0 |

Note: Dollar amounts are adjusted for inflation to constant 2019 dollars using the CPI-U-RS. Number of Wage and Hour Division investigations and average back wages per employee owed for this employer between FY05 and FY19.

Source: Authors' analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Compliance Action Data (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f).

No consistent pattern of compliance for repeat violators: Rio Fresh in Texas was investigated almost 70 times during fiscal years 2005–2019

| Investigation number | Avg back wages per employee |

|---|---|

| 1 | $0 |

| 2 | $0 |

| 3 | $0 |

| 4 | $0 |

| 5 | $0 |

| 6 | $0 |

| 7 | $0 |

| 8 | $0 |

| 9 | $0 |

| 10 | $0 |

| 11 | $0 |

| 12 | $0 |

| 13 | $0 |

| 14 | $0 |

| 15 | $0 |

| 16 | $72 |

| 17 | $0 |

| 18 | $0 |

| 19 | $0 |

| 20 | $0 |

| 21 | $0 |

| 22 | $0 |

| 23 | $0 |

| 24 | $0 |

| 25 | $0 |

| 26 | $0 |

| 27 | $0 |

| 28 | $0 |

| 29 | $0 |

| 30 | $0 |

| 31 | $0 |

| 32 | $0 |

| 33 | $0 |

| 34 | $0 |

| 35 | $28 |

| 36 | $0 |

| 37 | $0 |

| 38 | $0 |

| 39 | $0 |

| 40 | $0 |

| 41 | $0 |

| 42 | $0 |

| 43 | $0 |

| 44 | $0 |

| 45 | $45 |

| 46 | $54 |

| 47 | $0 |

| 48 | $0 |

| 49 | $0 |

| 50 | $0 |

| 51 | $0 |

| 52 | $0 |

| 53 | $0 |

| 54 | $0 |

| 55 | $0 |

| 56 | $0 |

| 57 | $0 |

| 58 | $0 |

| 59 | $0 |

| 60 | $0 |

| 61 | $0 |

| 62 | $0 |

| 63 | $0 |

| 64 | $0 |

| 65 | $0 |

| 66 | $0 |

Note: Dollar amounts are adjusted for inflation to constant 2019 dollars using the CPI-U-RS. Number of Wage and Hour Division investigations and average back wages per employee owed for this employer between FY05 and FY19.

Source: Authors' analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Compliance Action Data (U.S. DOL-WHD 2020f).

Figures O–Q show there was no pattern to back wages owed per affected employee for farms that were investigated multiple times. For example, J&D Produce was investigated more than 40 times before any back wages were found to be owed, and then investigated another 60 times before more back wages were found to be owed. The data do not indicate a declining pattern of back wages owed as farms came into compliance; sometimes zero back wages were owed after an investigation, punctuated by one or two subsequent investigations that found back wages owed.

Stockton, California-based FLC Jose M. Magdaleno was the most investigated agricultural employer in the state. Figure R shows that the first five investigations of Magdaleno found back wages of up to $320 per employee due, after which there were 10 investigations with no back wages assessed, followed by a more recent investigation that found back wages of $94 owed per affected employee. While the amount of back wages associated with Magdaleno had a general downward trend, the most recent investigations still found significant amounts of back wages owed to workers. Some California farm employers, including Sun World International, Richard Bagdasarian Inc., and OM Contracting, were investigated more than five times, and no back wages were found to be owed to employees.

No consistent pattern of compliance for farm labor contractors who are repeat violators: Jose M. Magdaleno in California was investigated 16 times during fiscal years 2005–2019

| Investigation number | Avg back wages per employee |

|---|---|

| 1 | $198 |

| 2 | $169 |

| 3 | $209 |

| 4 | $321 |

| 5 | $237 |

| 6 | $0 |