Executive Summary

On the surface, crime and punishment appear to be unsophisticated matters. After all, if someone takes part in a crime, then shouldn’t he or she have to suffer the consequences? But dig deeper and it is clear that crime and punishment are multidimensional problems that stem from racial prejudice justified by age-old perceptions and beliefs about African Americans. The United States has a dual criminal justice system that has helped to maintain the economic and social hierarchy in America, based on the subjugation of blacks, within the United States. Public policy, criminal justice actors, society and the media, and criminal behavior have all played roles in creating what sociologist Loic Wacquant calls the hyperincarceration of black men. But there are solutions to rectify this problem.

To summarize the major arguments in this essay, the root cause of the hyperincarceration of blacks (and in particular black men) is society’s collective choice to become more punitive. These tough-on-crime laws, which applied to all Americans, could be maintained only because of the dual legal system developed from the legacy of racism in the United States. That is, race allowed for society to avoid the trade-off between societies “demand” to get tough on crime and its “demand” to retain civil liberties, through unequal enforcement of the law. In essence, tying crime to observable characteristics (such as race or religious affiliation) allowed the majority in society to pass tough-on-crime policies without having to bear the full burden of these policies, permitting these laws to be sustained over time.

What’s more, the history of racism, which is also linked to the history of perceptions of race and crime, has led society to choose to fight racial economic equality using the criminal justice system (i.e., incarceration) instead of choosing to reduce racial disparities through consistent investments in social programs (such as education, job training, and employment, which have greater public benefits), as King (1968) lobbied for before his assassination. In other words, society chose to use incarceration as a welfare program to deal with the poor, especially since the underprivileged are disproportionately people of color.

At the same time, many communities attempted to benefit economically from mass incarceration by using prisons as a strategy for economic growth, making the incarceration system eerily similar to the system of slavery. Given all of the documented social and economic costs of mass incarceration (e.g., inferior labor market opportunities, increases in the racial disparity in HIV/AIDS, destruction of the family unit), it can be concluded that it has helped to maintain the economic hierarchy, predicated on race, in the United States. In order to undo the damage that has been done, and in order to move beyond our racial past, we must as a nation reeducate ourselves about race; and then, as a society, commit to investing in social programs targeted toward at-risk youth. We must also ensure diversity in criminal justice professionals in order to achieve the economic equality that King fought for prior to his death. Although mass incarceration policies have recently received a great deal of attention (due to incarceration becoming prohibitively costly), failure to address the legacy of racism passed down by our forefathers and its ties to economic oppression will only result in the continued reinvention of Jim Crow.

This is part of a series of reports from the Economic Policy Institute outlining the steps we need to take

as a nation to fully achieve each of the goals of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

Visit www.unfinishedmarch.com for updates and to join the Unfinished March.

The powerful never lose opportunities – they remain available to them. The powerless on the other hand, never experience opportunity – it is always arriving at a later time.—Martin Luther King Jr. (King 1968/2010, 1612)

Introduction

Hope and fear are two of the most effective tools of persuasion. Martin Luther King Jr. persuaded the hearts of a nation, and the world, with a message of hope. In fact, President Obama became the first black president of the United States, following in Dr. King’s footsteps, using hope as the cornerstone of his campaign. On the surface, Obama seemed to fulfill the roadmap for change that King provided 51 years ago in his “I Have a Dream” speech during the March on Washington. After all, a black man was voted into the highest office in the nation (arguably the world) during a time when only 13 percent of the nation self-identified as black (U.S. Census Bureau 2013). Surely, the fact that a majority of the nation cast their vote for a black president, not once but twice, indicates that the United States has made significant progress with race relations.

While Barack Obama’s ascension to the White House does suggest that we have made significant progress since the abolition of slavery, the fight for equality is far from over. After all, there are always exceptions to every rule. King did not stop his fight once African Americans attained “equality” under the law because he understood that such equality was actually costless and that the real price that society would have to pay for reversing the mass oppression of a people would come in delivering economic parity:

The practical cost of change for the nation up to this point has been cheap. The limited reforms have been obtained at bargain rates. There are no expenses, and no taxes are required, for Negroes to share lunch counters, libraries, parks, hotels and other facilities with whites. (King 1968/2010, 197)

In fact, in his last book, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?, King (1968/2010) eloquently reasons that the real dilemma for American society is whether or not to ensure economic equality through equal pay and equal investments in human capital. Such equality would come at a much greater cost than simply allowing a group of marginalized individuals the right to vote because “… jobs are harder and costlier to create than voting rolls” (p. 202). As King wrote, the then assistant director of the Office of Economic Opportunity, Hyman Bookbinder, estimated the long-term costs of insuring true social equality to be roughly one trillion dollars (p. 205). Apparently, Bookbinder did not believe this to be a daunting task, asserting that “‘…the poor [could] stop being poor if the rich [were] willing to become even richer at a slower rate’” (p. 205).

Nonetheless, true acceptance and complete integration into the social fabric of society would only come through an overhaul of the American social structure. As he sought genuine social change, King began to encounter heightened resistance, even among white liberals who openly supported the civil rights movement, due to political backlash as fear of losing white privilege began to invade the momentum of the movement (King 1968/2010; Steinberg 1998). However, King intuitively understood that there could be no social justice without economic justice because the persistence of economic inequality (e.g., lower wages for equivalent jobs) meant the preservation of the social hierarchy that defined blacks as only partly human. While the distinction ceased to persist in the letter of the law, it continued to be true within the U.S. economic structure.

It is well documented that the U.S. first garnered recognition on the international science scene through polygeny, a theory, mostly of American descent, that postulated that different races originated from different ancestors, with whites holding a superior status to all other groups. This “science” perpetuated the long held beliefs in the United States that African Americans are a degenerate race of individuals that have an inferior intellect, that are prone to criminal behavior, and that are not equipped to govern themselves (Frederickson 1971; Steinberg 1998; A.Y. Davis 1998; Gould 1996; Wacquant 2000). In fact, these opinions are still held and are documented today in social psychology experiments that find that black criminals are typically seen as more immoral than whites who commit similar crimes (Graham and Lowery 2004).

King (1968/2010) advised that in order to progress towards true equality whites would have to put forth “…a mass effort to reeducate themselves out of their racial ignorance” (p. 243). Nonetheless, instead of addressing the structural barriers that kept black Americans from achieving true social justice in a laissez-fair economy, it could be argued that mainstream society used the problems in the black community, which were themselves attributable to systematic oppression, as proof of why blacks were “undeserving” of this public investment (King, 1968/2010; Steinberg 1998; A.Y. Davis 1998; Crenshaw 1998; Wacquant 2000). In fact, one reason the “Moynihan Report” became so prominent was because of its characterization of the African American community as socially pathological, even though in the report then-Assistant Secretary of Labor Daniel Patrick Moynihan attributes this “pathology” to years of oppression of the black community (U.S. Department of Labor 1965; Acs et al. 2013).

At the same time, the protest and riots of the 1960s linked the movement for equality to crime and racial violence. Growing racial tension allowed for tough on crime policies as major agenda items in election campaigns that would later pave the way for policies that led to the mass incarceration of mostly black men (Tonry 1995; Loury 2008; Western and Wildeman 2008; Raphael and Stoll 2013). Issues of race and class lie at the heart of the problem of mass incarceration, making it very complex. In fact, it can be argued that the disproportionate incarceration rate of minorities in general, and blacks in particular, is one of the most pressing civil rights issues of our time (Alexander 2010; Loury 2008; Wacquant 2008; Wacquant 2000), and an issue whose consequences extend beyond the inmate to the destruction of families and communities.

On the surface, crime and punishment appear to be unsophisticated matters. After all, if someone takes part in a crime, then shouldn’t he or she have to suffer the consequences of such actions? Nonetheless, it is argued throughout this essay that crime and punishment are multidimensional problems that are inherently tied to institutionalized racial prejudice justified by age-old perceptions and beliefs about African Americans. It is purported that the criminal justice system has become a tool used to maintain the economic and social hierarchy within the United States based on the subjugation of blacks. In the remainder of this essay I will discuss the roles that public policy, criminal justice actors, society and the media, and criminal behavior have played in creating what sociologist Loic Wacquant calls the hyperincarceration of black men. I will then discuss possible solutions to rectify this problem.

How did we get here? The causes of mass incarceration

Although mass incarceration can be attributed to public policy, these policies were sustained over time because of institutionalized racism. The disproportionate imprisonment of African Americans that ensued resulted from the link between perceptions of race and crime, and the subconscious desire to maintain the American economic social structure, which places blacks at the bottom and whites at the top.

Public policy

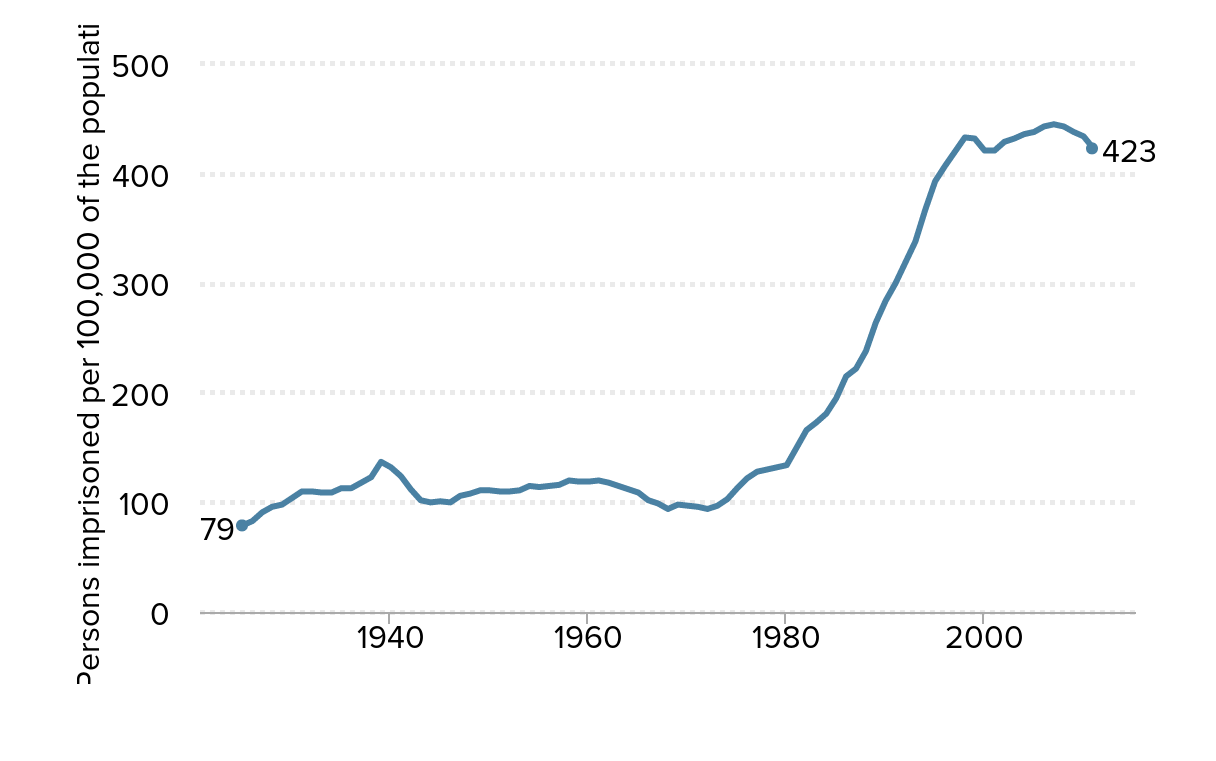

Rate of imprisonment in state or federal correctional facilities, 1925–2011

| Year | Imprisonment rate |

|---|---|

| 1925 | 79 |

| 1926 | 83 |

| 1927 | 91 |

| 1928 | 96 |

| 1929 | 98 |

| 1930 | 104 |

| 1931 | 110 |

| 1932 | 110 |

| 1933 | 109 |

| 1934 | 109 |

| 1935 | 113 |

| 1936 | 113 |

| 1937 | 118 |

| 1938 | 123 |

| 1939 | 137 |

| 1940 | 132 |

| 1941 | 124 |

| 1942 | 112 |

| 1943 | 102 |

| 1944 | 100 |

| 1945 | 101 |

| 1946 | 100 |

| 1947 | 106 |

| 1948 | 108 |

| 1949 | 111 |

| 1950 | 111 |

| 1951 | 110 |

| 1952 | 110 |

| 1953 | 111 |

| 1954 | 115 |

| 1955 | 114 |

| 1956 | 115 |

| 1957 | 116 |

| 1958 | 120 |

| 1959 | 119 |

| 1960 | 119 |

| 1961 | 120 |

| 1962 | 118 |

| 1963 | 115 |

| 1964 | 112 |

| 1965 | 109 |

| 1966 | 102 |

| 1967 | 99 |

| 1968 | 94 |

| 1969 | 98 |

| 1970 | 97 |

| 1971 | 96 |

| 1972 | 94 |

| 1973 | 97 |

| 1974 | 103 |

| 1975 | 113 |

| 1976 | 122 |

| 1977 | 128 |

| 1978 | 130 |

| 1979 | 132 |

| 1980 | 134 |

| 1981 | 150 |

| 1982 | 166 |

| 1983 | 173 |

| 1984 | 181 |

| 1985 | 195 |

| 1986 | 215 |

| 1987 | 222 |

| 1988 | 238 |

| 1989 | 264 |

| 1990 | 284 |

| 1991 | 300 |

| 1992 | 319 |

| 1993 | 338 |

| 1994 | 367 |

| 1995 | 393 |

| 1996 | 407 |

| 1997 | 420 |

| 1998 | 433 |

| 1999 | 432 |

| 2000 | 421 |

| 2001 | 421 |

| 2002 | 429 |

| 2003 | 432 |

| 2004 | 436 |

| 2005 | 438 |

| 2006 | 443 |

| 2007 | 445 |

| 2008 | 443 |

| 2009 | 438 |

| 2010 | 434 |

| 2011 | 423 |

Source: Author's calculation of Minor-Harper (1986) and Carson and Mulako-Wangota (2013)

Over the past 40 years U.S. incarceration has grown at an extraordinary rate. However, this has not always been the case. Figure A provides historical estimates of the imprisonment rate in state and federal facilities and it demonstrates that from 1925 until about the middle of the 1970s the rate did not rise above 140 persons imprisoned per 100,000 of the population. However, the extraordinary growth of the imprisonment rate after 1974 eventually led to unprecedented levels of incarceration. While the increase in incarceration could be driven by changes in policy and/or changes in criminal behavior, Raphael and Stoll (2013) find that the lion’s share of the growth in the prison population can be accounted for by society’s choice for tough-on-crime policies (e.g., determinate sentencing, truth-in-sentencing laws, limiting discretionary parole boards, etc.) resulting in more individuals (committing less serious offenses) being sentenced to serve time, and longer prison sentences. Stated differently, individuals are imprisoned for crimes that they would not have been incarcerated for in the past, and those who committed offenses that would have previously warranted confinement receive much longer prison terms. Lastly, a large fraction of society is on parole, and parolees are more likely to violate parole and return to prison than in the past (Raphael and Stoll 2013). Raphael and Stoll (2013) attribute no more than 9 percent of the increase in state incarceration since 1984 to changes in criminal behavior. They find little to no evidence for the most common factors posited for the extraordinary increase in the U.S. incarceration rate: 1) changes in the relative returns to legal activity (e.g., declining low-skill wages) relative to illegal activity (changes in drug markets in general, and crack cocaine in particular), 2) increases in criminal behavior (e.g., violent crime) due to the introduction of crack cocaine, and 3) the deinstitutionalization of the mentally ill.

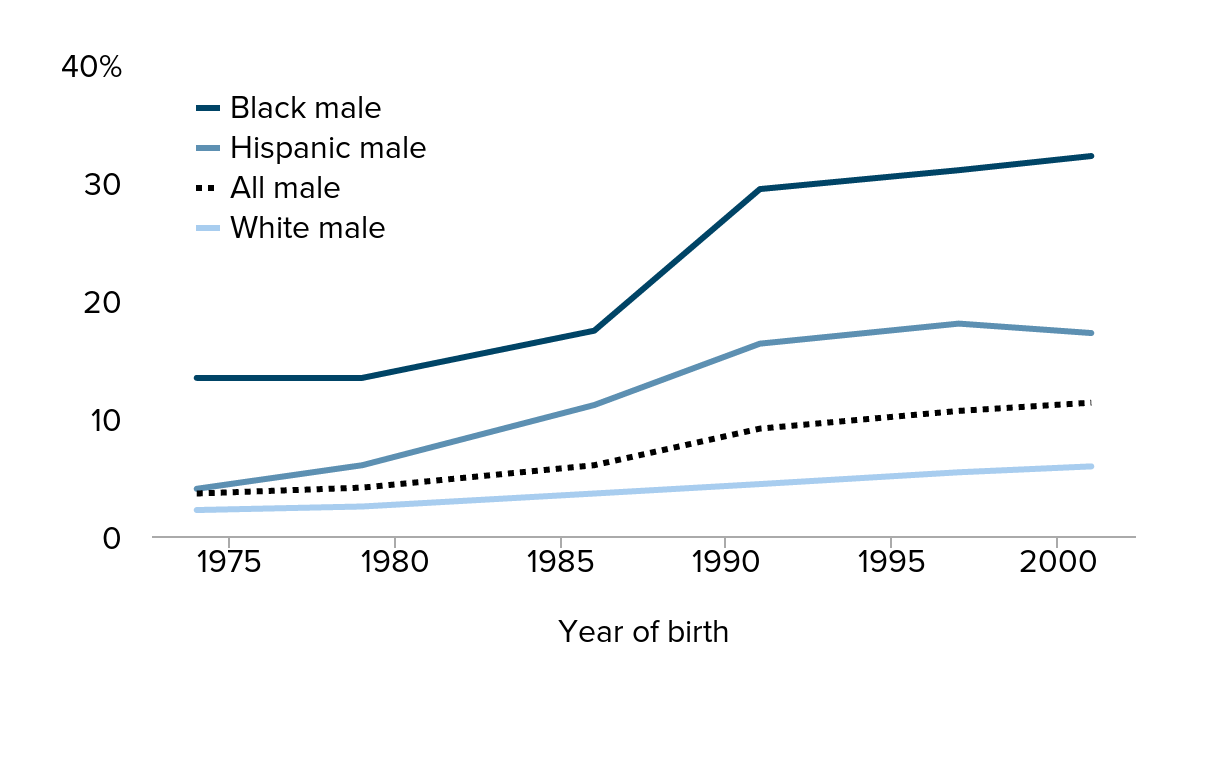

Male lifetime likelihood of going to state or federal prison, by race and ethnicity, 1974–2001

| Black male | White male | Hispanic male | All male | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1974 | 13.4% | 2.2% | 4% | 3.6% |

| 1979 | 13.4 | 2.5 | 6 | 4.1 |

| 1986 | 17.4 | 3.6 | 11.1 | 6 |

| 1991 | 29.4 | 4.4 | 16.3 | 9.1 |

| 1997 | 31 | 5.4 | 18 | 10.6 |

| 2001 | 32.2 | 5.9 | 17.2 | 11.3 |

Notes: The black and white categories exclude persons of Hispanic origin. Percents represent the chances of being admitted to state or federal prison during a lifetime. Estimates were obtained by applying age-specific first incarceration and mortality rates for each group to a hypothetical population of 100,000 births. See methodology section in Bonczar (2003).

Source: Bonczar (2003)

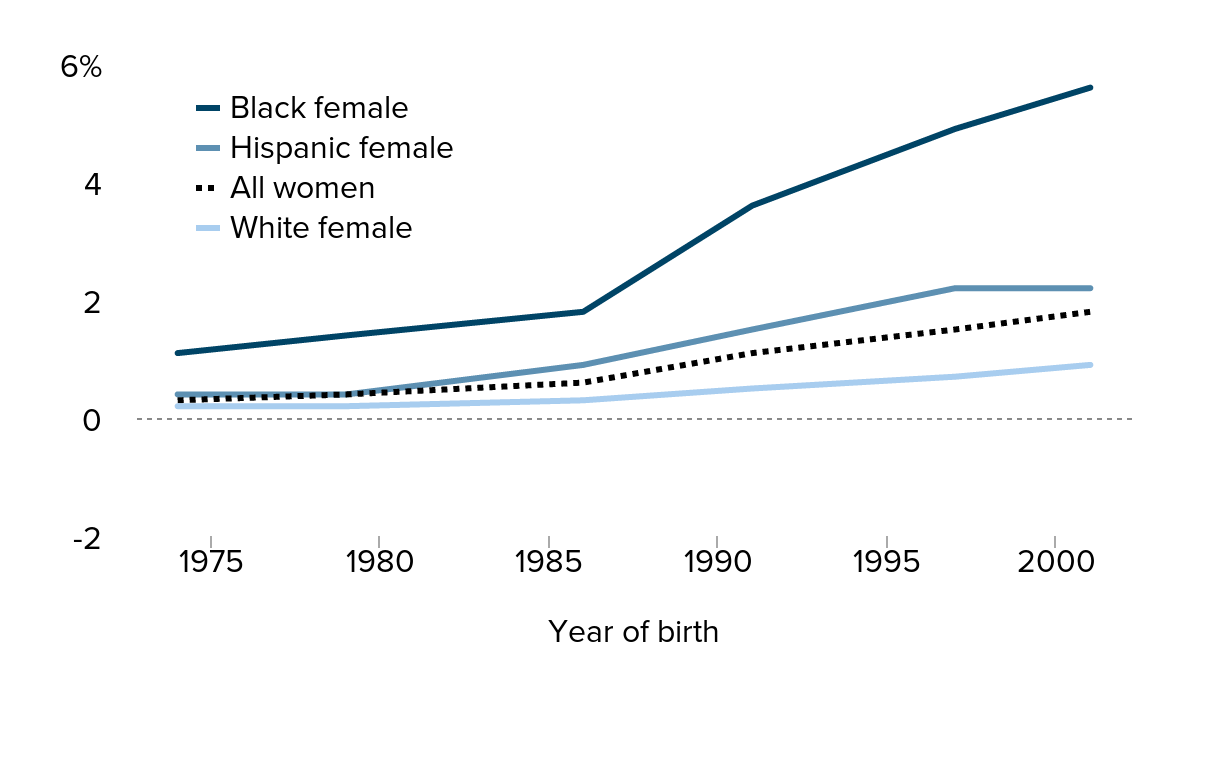

Female lifetime likelihood of going to state or federal prison, by race and ethnicity, 1974–2001

| Black female | White female | Hispanic female | All women | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1974 | 1.1% | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.3% |

| 1979 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| 1986 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.6 |

| 1991 | 3.6 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 1.1 |

| 1997 | 4.9 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 1.5 |

| 2001 | 5.6 | 0.9 | 2.2 | 1.8 |

Notes: The black and white categories exclude persons of Hispanic origin. Percents represent the chances of being admitted to state or federal prison during a lifetime. Estimates were obtained by applying age-specific first incarceration and mortality rates for each group to a hypothetical population of 100,000 births. See methodology section in Bonczar (2003).

Source: Bonczar (2003)

Figures B and C plot the lifetime likelihood of a first incarceration at a state or federal prison for individuals born between 1974 and 2001disaggregated by race and ethnicity for men and women respectively. The lifetime likelihood of a first incarceration has greatly increased over time and this is especially true for blacks and Hispanics. The rate of change for men is greatest between 1986 and 1991 while the rate of change for women is highest between 1986 and 1997.1 The years of the extreme increase in slope coincides with the Reagan administration’s enhancement of Nixon’s war on drugs2 through the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986. One significant piece of this legislation, which is held responsible for the disproportionate rates of incarceration among African Americans in federal prisons, is the mandatory minimums for drug offenses including the disparities in sentencing between cocaine and the cheaper crack cocaine (see Raphael and Stoll 2013). However, the version of this bill passed in 1988 also provided substantial monetary incentives for state and local police agencies to implement the war on drugs (which was not previously a priority) through the Edward Byrne Memorial State and Local Law Enforcement Assistance Program (Byrne Program).

A 1993 GAO report states: “Byrne program grants are the primary source of federal financial assistance for state and local drug law enforcement efforts” (GAO 1993, 2). This grant, along with civil forfeiture laws passed in 1984 allowing state and local police to share in drug-related assets, provided substantial resources to state and local law enforcement to focus on the drug war. Arguably these monetary incentives, coupled with Supreme Court rulings empowering police with unprecedented discretion to stop and search citizens with little to no probable cause, have played a role in the excessive incarceration rates we see today and the disproportionate imprisonment of African Americans (Alexander 2010; Sandy 2002; Benson and Rasmussen 1996; Blumenson and Nilsen 1998; Tieger 1971; and Russell 1998).

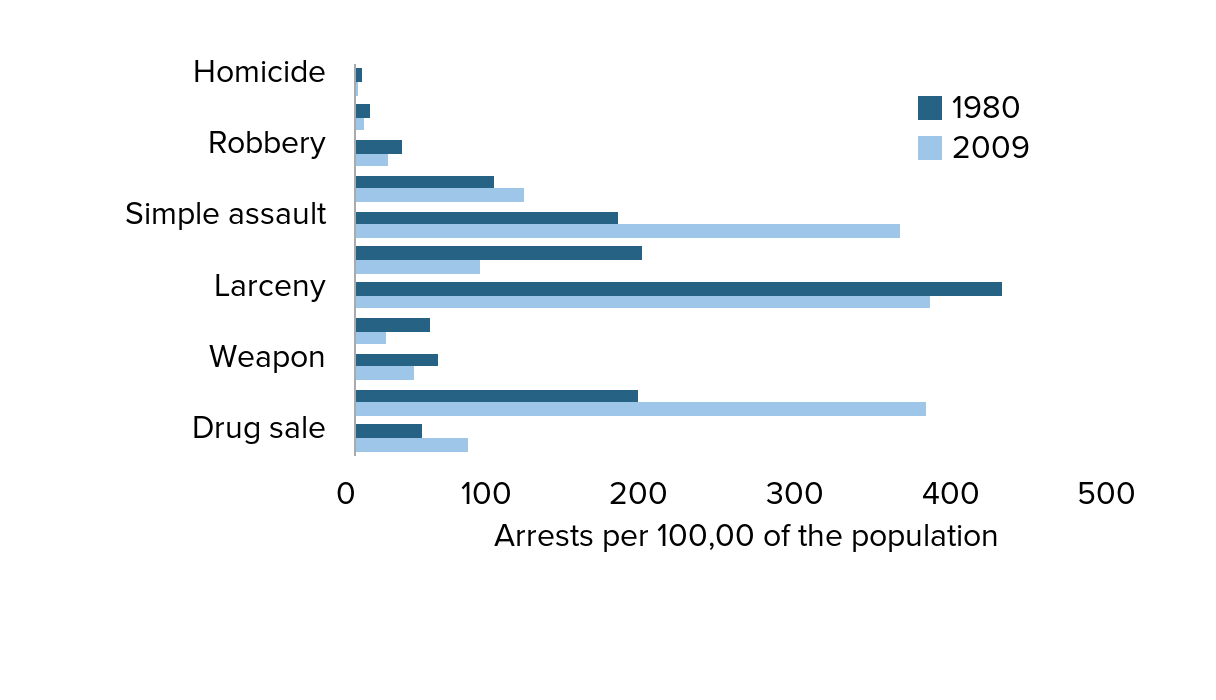

White arrest rates by offense type, 1980 and 2009

| 1980 | 2009 | |

|---|---|---|

| Homicide | 5.3 | 2.5 |

| Rape | 9.9 | 6.4 |

| Robbery | 30.9 | 22 |

| Aggravated assault | 89.6 | 108.8 |

| Simple assault | 168.6 | 350.2 |

| Burglary | 184.8 | 81 |

| Larceny | 415 | 369 |

| Motor vehicle theft | 48.6 | 20.3 |

| Weapon | 53.9 | 38.8 |

| Possession | 182.1 | 367.3 |

| Drug sale | 43.7 | 72.5 |

Source: Author's calculation from Snyder (2011) for 1980 data and FBI Uniform Crime Reporting Program data (U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation 2009) for 2009

Black arrest rates by offense type, 1980 and 2009

| 1980 | 2009 | |

|---|---|---|

| Homicide | 35 | 14.8 |

| Rape | 70.7 | 19.7 |

| Robbery | 314.3 | 171.5 |

| Aggravated assault | 366.6 | 344.8 |

| Simple assault | 569.6 | 1023.8 |

| Burglary | 544.7 | 229 |

| Larceny | 1337.6 | 941.1 |

| Motor vehicle theft | 151.8 | 71.7 |

| Weapon | 221.5 | 165.4 |

| Possession | 341 | 1039.6 |

| Drug sale | 163.9 | 311.6 |

Source: Author's calculation from Snyder (2011) for 1980 data and FBI Uniform Crime Reporting Program data (U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation 2009) for 2009

Percentage change in arrests, by race, 1980–2009

| White | Black | |

|---|---|---|

| Homicide | -53 | -58 |

| Rape | -35 | -72 |

| Robbery | -29 | -45 |

| Aggravated assault | 21 | -6 |

| Burglary | -56 | -58 |

| Larceny | -11 | -30 |

| Motor vehicle theft | -58 | -53 |

| Simple assault | 108 | 80 |

| Weapons | -28 | -25 |

| Drug possession | 102 | 205 |

| Drug sales | 66 | 90 |

Source: Author's calculation from Snyder (2011) for 1980 data and FBI Uniform Crime Reporting Program data (U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation 2009) for 2009

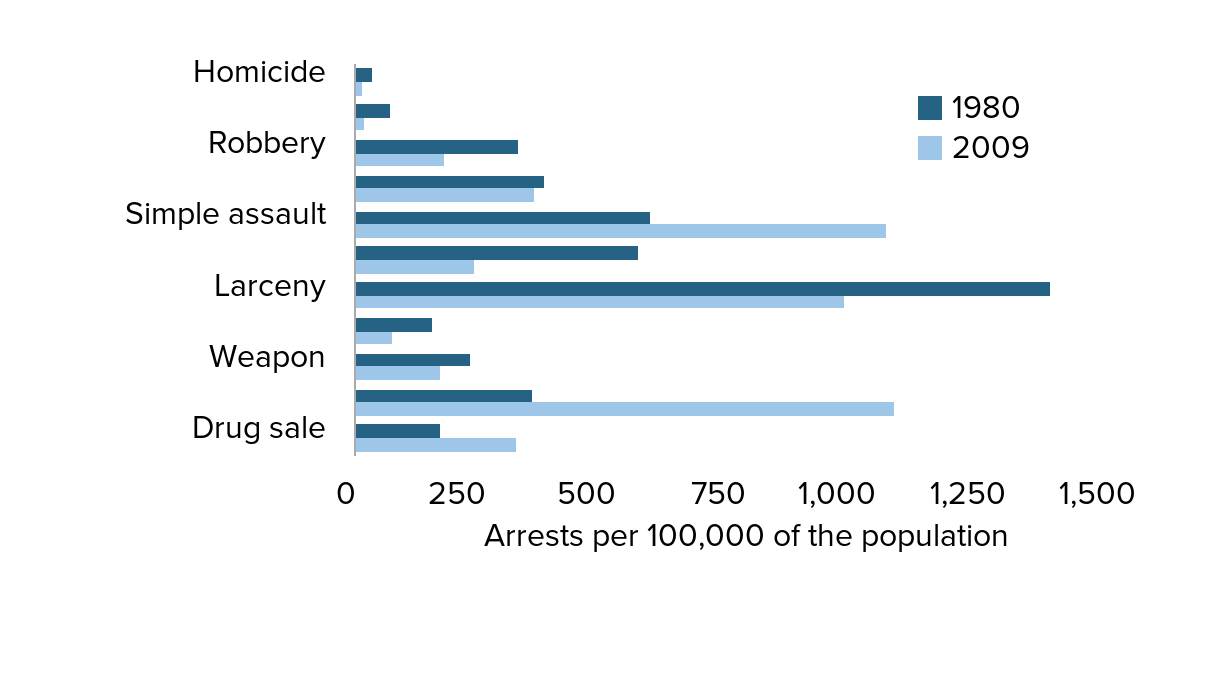

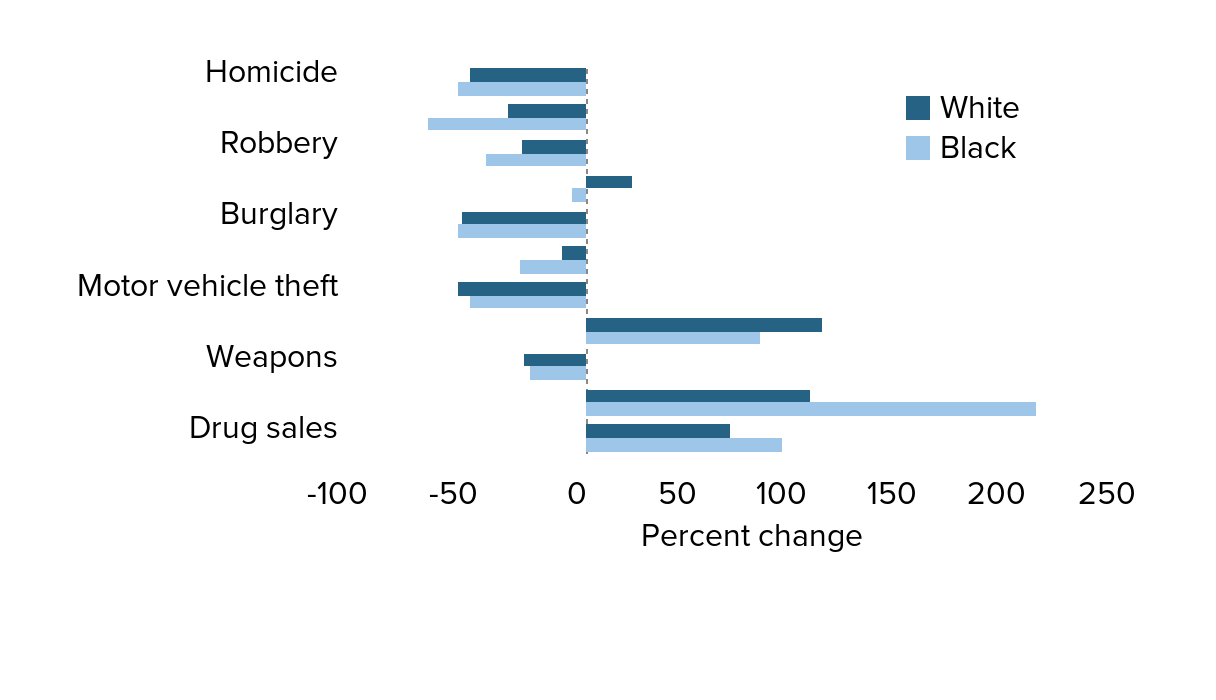

Although arrest rates and incarceration rates are often used to gauge criminal activity, they are not pure measures of such behavior because they also reflect policy decisions as well as biases due to selective law enforcement. Figure D shows arrest rates in 1980 and 2009 for whites, Figure E provides the same data for blacks, and Figure F provides the percentage change in arrests over this period for blacks and whites for each crime category displayed. Figures D and E show that African Americans have much higher arrest rates than whites in every category. Figure F illustrates that except for whites arrested for aggravated assault, all other Index Part I crimes (homicide, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny, and motor vehicle theft) decreased for both blacks and whites. The only other crimes to experience significant increases in arrest from 1980 to 2009 are the less serious offenses of simple assault, drug possession, and drug sales.

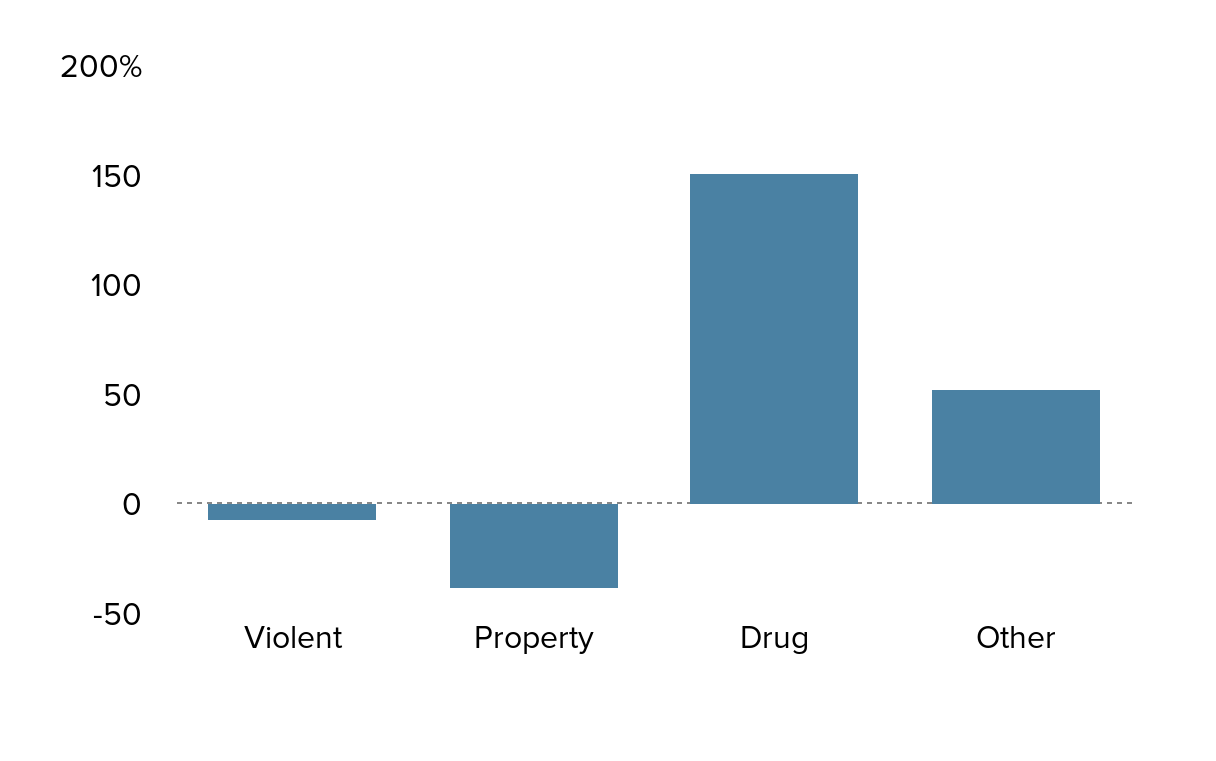

Figure G shows how the shift in focus to less serious crimes translated into changes in the distribution of offenses for individuals incarcerated in state prison from 1979 to 2009. It is clear from the figure that there was a decrease in the share of individuals sentenced to state facilities for violent crimes and property crimes, but large increases in imprisonment for less serious crimes such as drug crimes and other crimes, echoing the findings by Raphael and Stoll (2013) that a sizeable portion of the increase in incarceration was due to a focus on less serious offenses such as nonviolent drug offenses.3

Percentage change in the distribution of state prison offenses, 1979–2009

| Category | Percentage change |

|---|---|

| Violent | -7% |

| Property | -38 |

| Drug | 151 |

| Other | 52 |

Source: Author's calculations from Guerino et al. (2011) and U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics (1982)

Although policing decisions are typically made at the state and local levels, the federal government can still influence local law enforcement choices through laws and intergovernmental grant programs. These concessions (discussed above) were offered to state and local law authorities in order to garner support for the war on drugs. Such allowances (e.g., civil forfeiture laws and Edward Byrne Memorial grants) are dangerous for two reasons: 1) as demonstrated above, these programs distort policy and monitoring decisions, and 2) these laws produce “…self-financing, unaccountable law enforcement agencies divorced from any meaningful legislative oversight” (Blumenson and Nilsen, 1998). Within a public choice framework, more police resources do not necessarily lead to lower crime rates. On the contrary, such allowances may provide police with motives to keep crime/arrest rates high since arrest rates are a measure of their efficacy and demand, and are now tied to federal funding. Thus, the availability of these targeted resources could explain police agencies switching focus to drugs (as well as other Part II crimes, such as simple assault) along with the increasing criminalization of less-serious offenses leading to prisons becoming filled with low-level drug offenders (Andreozzi 2004; Benson and Rasmussen 1996: Benson, Kim, and Rasmussen 1994).

At the same time, impoverished rural communities began seeking to use prison construction as part of their economic development strategies. Political officials hoped prisons would be a recession-proof industry that would help to stimulate their economies through job creation and regional multiplier effects (Farrigan and Glasmeier 2007; Kirchhoff 2010). Among 1,500 prison facilities constructed by 1995, Farrigan and Glasmeier (2007) find that 39 percent were located in rural communities, with the rural facilities holding higher percentages of males and blacks than urban prisons. In addition, the private sector also began to view the expanding prison population as a source of economic opportunity (Cheung 2002).

Putting the pieces of the puzzle together leads to the following system of mass incarceration: more punitive crime policies and a national push for the drug war (for political gain), which led state and local law enforcement to shift their focus to policing and punishing less serious lawbreakers such as drug offenders and those committing simple assault,4 which in turn spurred a boom in the prison population causing state and local officials to lobby for prison construction as a tool for economic growth and leading private industry to seek opportunities for profit among the incarcerated. The end result is political and economic systems reliant on communities in chaos (also see a discussion of this by Loury 2008). While the preceding thoughts may shed light on the growth in the incarcerated population, they do not explain how African Americans, who make up less than 13 percent of the population, came to account for over half of the prison population during the height of the prison boom.

Perceptions of race, criminality, and social stratification

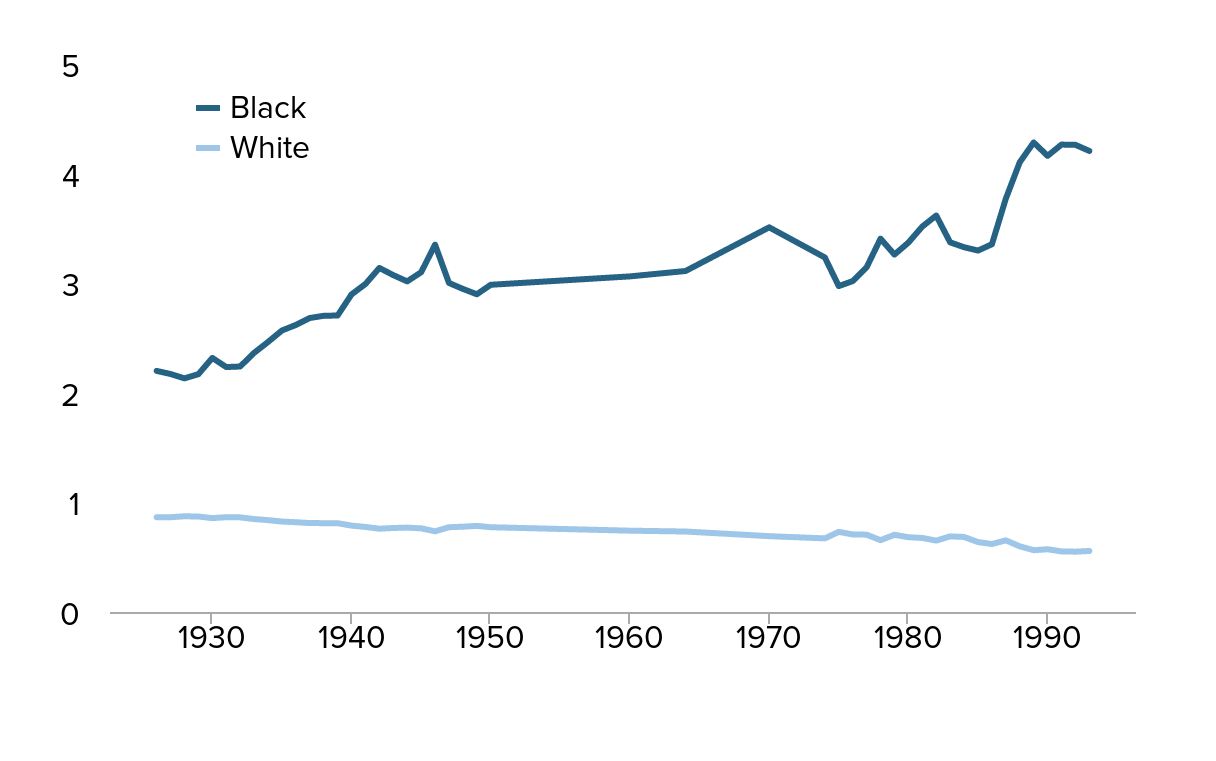

Black children born in 2001 are roughly 5.5 times more likely than their white counterparts to be incarcerated (Bonczar 2003). However, taken from a historical perspective this disparity is not unusual. By analyzing the ratio of the proportion of prison admissions rates to the proportion of the population by race (see Figure H) from 1926 to 1993, it is clear that blacks have historically experienced incarceration rates above their proportion in society. Nonetheless, it is also apparent that the disparity has become exacerbated over time. From a political economy perspective, it could be argued that the prison system has been used as a tool to usurp black (and poor white) labor, as a form of social control during economic downturns, and as a method to maintain social order when poor marginalized groups (e.g., black men) with high rates of unemployment increase in size (Myers 1993; Wacquant 2000).

Ratio of proportion admitted to prison to share of population, by race, 1926–1993

| year | White | Black |

|---|---|---|

| 1926 | 0.8646896 | 2.199833 |

| 1927 | 0.8646989 | 2.17144 |

| 1928 | 0.8733817 | 2.131757 |

| 1929 | 0.8711722 | 2.17002 |

| 1930 | 0.8565032 | 2.318197 |

| 1931 | 0.8650528 | 2.23481 |

| 1932 | 0.8634449 | 2.239778 |

| 1933 | 0.8481098 | 2.364207 |

| 1934 | 0.8382051 | 2.46356 |

| 1935 | 0.8251895 | 2.56838 |

| 1936 | 0.8192377 | 2.618846 |

| 1937 | 0.8115541 | 2.682416 |

| 1938 | 0.8105729 | 2.702562 |

| 1939 | 0.8102447 | 2.705249 |

| 1940 | 0.7883061 | 2.897598 |

| 1941 | 0.7761271 | 2.992737 |

| 1942 | 0.7598836 | 3.139206 |

| 1943 | 0.7663909 | 3.073601 |

| 1944 | 0.77003 | 3.016577 |

| 1945 | 0.7632093 | 3.100061 |

| 1946 | 0.7362881 | 3.351378 |

| 1947 | 0.7734134 | 3.002343 |

| 1948 | 0.7783268 | 2.947933 |

| 1949 | 0.7855678 | 2.899025 |

| 1950 | 0.7734575 | 2.985587 |

| 1960 | 0.7420148 | 3.062132 |

| 1964 | 0.7342211 | 3.111357 |

| 1970 | 0.6919973 | 3.509817 |

| 1974 | 0.6716154 | 3.234681 |

| 1975 | 0.7310312 | 2.973519 |

| 1976 | 0.7077293 | 3.019088 |

| 1977 | 0.7055128 | 3.145308 |

| 1978 | 0.655506 | 3.406392 |

| 1979 | 0.7044626 | 3.261237 |

| 1980 | 0.6823106 | 3.370042 |

| 1981 | 0.6756689 | 3.516932 |

| 1982 | 0.6514124 | 3.617326 |

| 1983 | 0.6901026 | 3.37294 |

| 1984 | 0.6847866 | 3.328413 |

| 1985 | 0.6379915 | 3.297802 |

| 1986 | 0.6202134 | 3.355173 |

| 1987 | 0.6535816 | 3.771335 |

| 1988 | 0.5992618 | 4.103139 |

| 1989 | 0.564021 | 4.284014 |

| 1990 | 0.5723963 | 4.16193 |

| 1991 | 0.5528145 | 4.264695 |

| 1992 | 0.5504394 | 4.262562 |

| 1993 | 0.5566475 | 4.206541 |

Source: Author's calculations from Gibson and Jung (2002), National Prisoners Statistics (U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics), and Brown et al. (1996)

When the political and economic threat of these groups is low, society becomes less punitive. It can be reasoned that the political gains by African Americans during the civil rights movement, followed by the urban flight of manufacturing jobs and an increase in the unemployed, led to society’s desire to use the penal system to control black labor. Along the same lines, the penal system could also be viewed as a form of welfare for young, poor minority men. In fact, it can be argued that the criminal justice system in general, and prisons in particular, have become the primary method used to maintain the U.S. social structure predicated on the hegemony of whites, with blacks viewed by many as an underserving deviant group (Loury 2008). It could also be reasoned that after the civil rights movement made it socially and legally unacceptable to deny individual rights based on race, incarceration became the ideal tool to restore control and uphold this social order (Alexander 2010). In fact, empirical research has found that imprisonment is used to regulate excess black unemployment (Myers and Sabol 1987).

More recent research finds that there are strong effects of incarceration on employment and earnings (e.g., see Raphael and Stoll 2013, Pager 2003; Pager, Western, and Suggie 2009; Raphael 2014; and Pager, Western, and Bonikowski 2009), the burden of which is disproportionately felt in the black community, since African Americans are excessively incarcerated. Incarceration diminishes employment and earnings prospects, especially for young black men (Holzer 2009; Pager, Western, and Suggie 2009; Pager, 2003; Pager, Western, and Bonikowski 2009). Due to large numbers of black men incarcerated, it has also been found that black-white employment and earnings disparities have been underestimated (Western and Pettit 2000; Chandra, 2003). In particular, there is evidence that arrests may explain almost two-thirds of the black-white gap in employment for young men (Grogger 1992) and that incarceration explained one-third of this differential in 2000 (Raphael 2006). Moreover, new research suggests that the higher relative arrest rates of blacks compared to whites might limit black upward mobility, and lead to inferior occupational placements (e.g., preclude blacks from consideration for managerial positions, in which being absent—due to an arrest—is more costly to employers (Bailey 2014).5

After accounting for selection bias, Chandra (2003) estimates that black-white wage differentials actually diverged between 1980 and 1990, and that incarceration can account for almost 50 percent of this divergence. Western and Pettit (2005) also find that from 1980 to 1999, the black-white wage differential increased among working-age men after accounting for incarceration-induced selection bias.

Moreover, using audit studies, Pager (2003) and Pager, Western, and Bonikowski (2009), find that employment opportunities for minorities are hurt more by an incarceration. However, incarceration does not affect everyone in the same way: Low-skilled white males recently released from prison receive just as many, if not more call backs than blacks and Hispanics without a criminal record (Pager, Western, and Bonikowski 2009). It is interesting to note that, although low-skilled white male employment is hurt by an incarceration, previously incarcerated white men are still ranked in the economic hierarchy at the same level as low-skilled Hispanic and black men without criminal records.

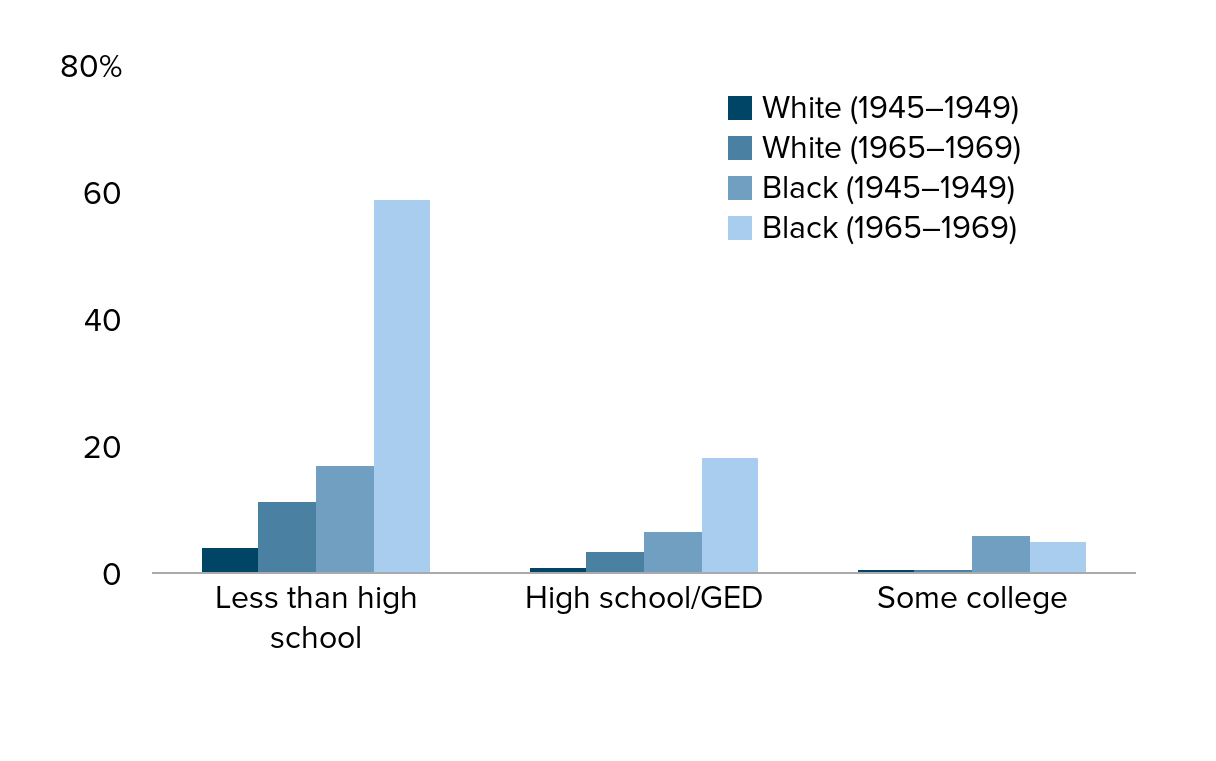

To further illustrate this point, Figure I (derived from estimates from Pettit and Western 2004) provides an estimate of the cumulative risk of imprisonment by age 30–34 for two different birth cohorts by race and education level. Regardless of race or birth cohort, education is associated with a significant decrease in the likelihood of incarceration. However, racial disparities in incarceration persist over time at all education levels.

Cumulative risk of imprisonment by ages 30–34, by education, race, and birth cohort

| White (1945–1949) | White (1965–1969) | Black (1945–1949) | Black (1965–1969) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than high school | 4% | 11.2 | 17.1 | 58.9 |

| High school/GED | 1 | 3.6 | 6.5 | 18.4 |

| Some college | 0.5 | 0.7 | 5.9 | 4.9 |

Source: Author's calculation of Pettit and Western (2004)

Finally, imprisonment leads to the loss of an individual’s ability to participate in the democratic process, and ultimately one’s citizenship, through felon disenfranchisement laws (Uggen, Manza, and Thompson 2006; Karlan 2008). The majority of states prohibit individuals in prison or on probation or parole from voting, and although numerous states have developed protocols for restoring voting privileges to ex-offenders, these procedures are so onerous that many do not seek to restore their rights (The Sentencing Project 2013).

Taking all of the above into consideration, there is ample evidence that the criminal justice system has played an integral part in maintaining social and economic stratification along racial lines (Western and Wildeman 2008; Alexander 2010; Wacquant 2008;Wacquant 2000; Myers 1993).

In conclusion, the civil rights movement threatened the political power of white privilege and, coupled with the flight of urban jobs (not necessarily two independent events), created a reserve of young, idle, unemployed black youth, which paved the way for more punitive (versus rehabilitative) policies toward crime. With the help of politicians and the news media, criminal and black has become so interchangeable that social psychology experiments testing implicit racial bias have generally found whites view blacks as less trustworthy, more violent, and innately criminal (Sommers and Ellsworth 2000; Dixon and Maddox 2005; Eberhardt et al. 2004; Payne, Shimizu, and Jacoby 2005; Correll et al. 2007). Other research suggests that white decisions on crime-fighting policies are influenced by racial stereotypes leading to the willingness to endorse more punitive approaches (i.e., building new prisons) versus investing in antipoverty methods when asked about fighting crime in the “inner city” (i.e., black community). This implies a greater willingness of society to use prison as the method for dealing with disadvantaged communities of color (Hurwitz and Peffley 2005).

The criminal justice system

Thus far, the root causes of the expansion of the prison population (public policy), the motive behind this growth (preservation of social hierarchy), and the tool used to achieve these goals (criminal justice system and prisons) have been identified. It is important to note that the suggested motive behind mass incarceration need not be intentional animus. Rather, it is proposed that racism is so ingrained in American society that it can operate similar to the invisible hand concept developed by Adam Smith to explain market equilibrium.6 However, there still remains the question: How did crime control policies that affected the entire public turn into a system for locking up a disproportionate share of African Americans?

The answer lies in the use of discriminatory enforcement (Loury 2008). Given the research discussed above, it is logical to infer that society is more tolerant of selective law enforcement in black neighborhoods. There are two criminal justice actors that play very important roles in discriminatory enforcement at the first point of contact with this system: 1) policing agencies, and 2) prosecutors. Police have vast discretion over whom they regulate and which violations, if any, they decide to charge. Legal scholars have written about the extraordinary, unchecked, discretion allotted to police officers and the effects this has on the application of the law (Tieger 1971; Cole 2001; Alexander 2010). One highly publicized “method” to carry out selective enforcement is racial profiling. It is often argued that policing based on race has merit if it is the result of statistical discrimination (i.e., race used as a signal to identify individuals that are more likely to commit a crime), which is thought to enhance policing efficiency. Therefore, much of the empirical literature attempts to identify whether racial profiling is statistically driven or whether it is preference-based discrimination. While empirical results vary based on the methods and data used,7 there are a number of empirical studies that suggest there is greater enforcement of criminal laws in communities of color. For example, some studies find that the race of the police officer matters in determining who will be monitored, which suggests preference-based profiling since statistical discrimination would imply that the officer’s race is inconsequential to enforcement decisions (Antonovics and Knight 2009; Close and Mason 2006; Close and Mason 2007; Donohue and Levitt 2001).8

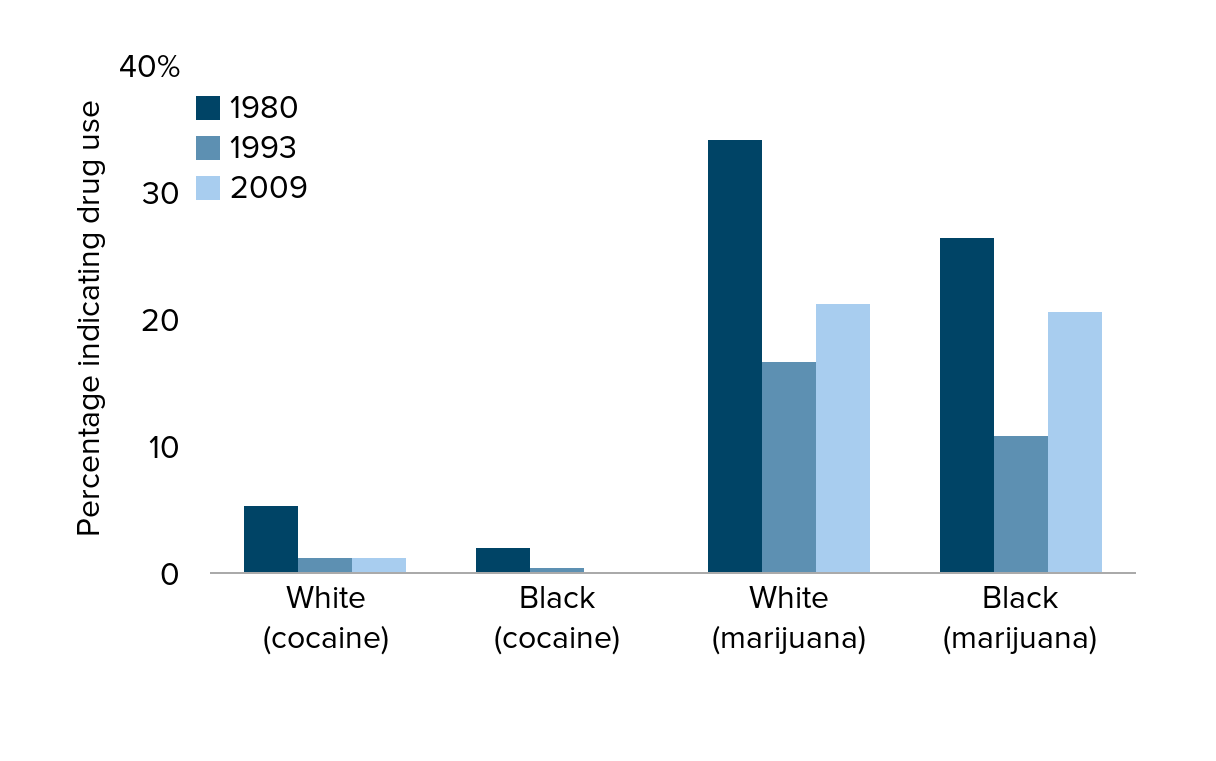

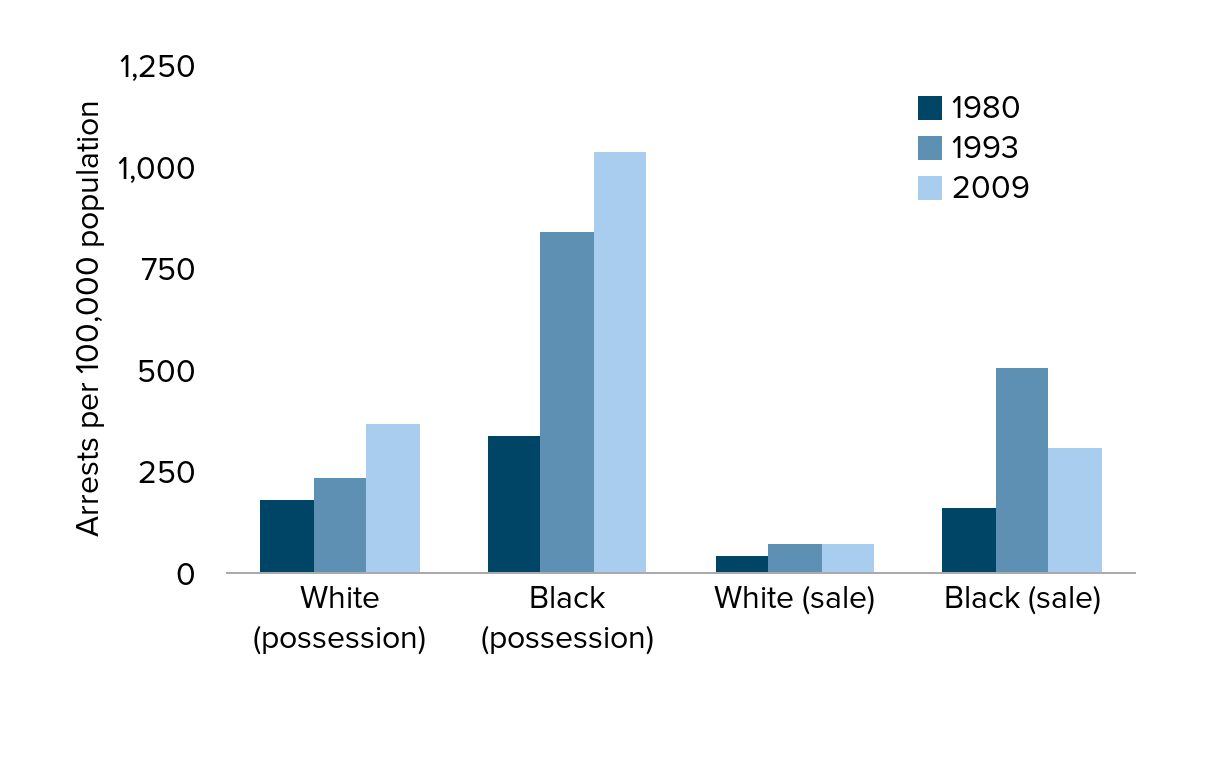

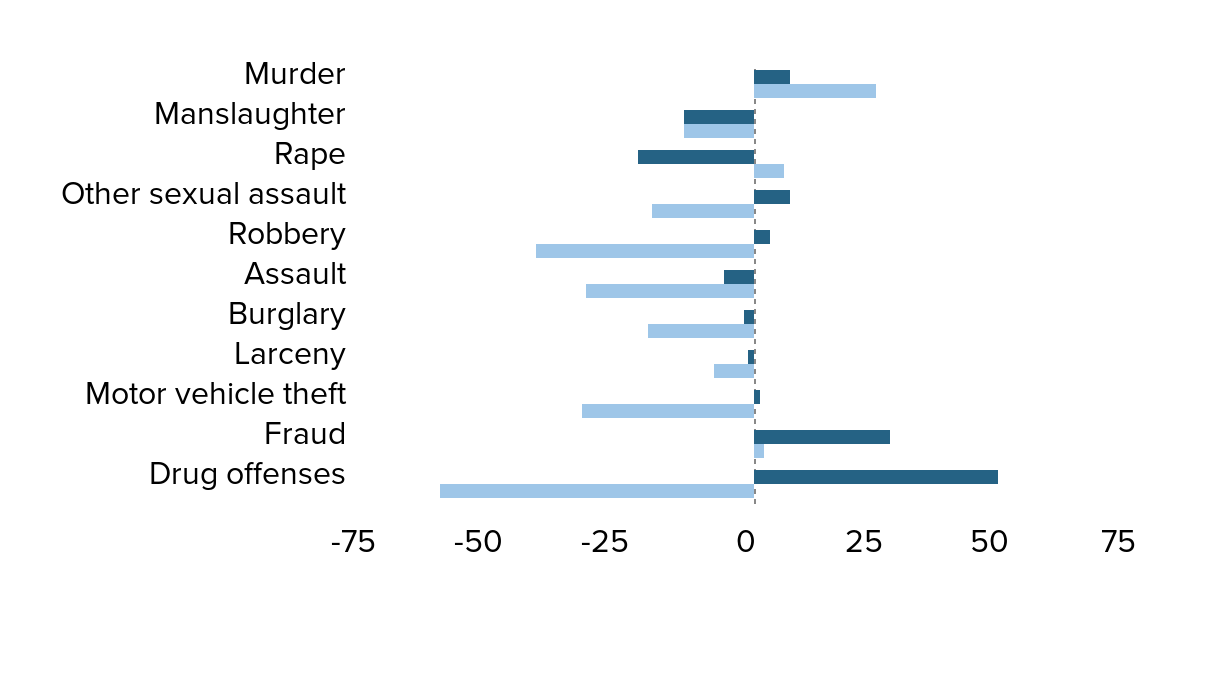

Evidence of racial profiling can also be seen by comparing drug use with drug arrest rates by race. In Figure J, black senior high school9 students indicate using cocaine and marijuana at lower rates in 1980, 1993, and 2009 than their white counterparts; however, Figure K shows that, in general, blacks are much more likely than whites to be arrested for possession and distribution of drugs. In fact, from 1980 to 2009 arrest rates for drug possession increased the most for blacks, with roughly a 205 percent change. Figure L suggests that this racially biased policing also led to a change in the distribution of offenses for which blacks were sentenced to state prisons from 1986–1999. The figure shows the percentage change in the proportion of total offenses committed by blacks and whites serving time in state prisons, by offense type. So, for example, the proportion of total murder offenses committed by blacks serving time in state facilities decreased by 7 percent, while whites’ share increased by 24 percent. Blacks saw the greatest change with drug offenses, their share increased by 50 percent. Since arrest rates reflect policy decisions, racial bias, and criminal behavior, they are more appropriately viewed as an indicator of the probability of enforcement versus criminal behavior. It is clear from figures K and L that blacks face a higher level of enforcement and punishment than whites. As mentioned earlier, it is possible that higher arrest rates reflect higher criminality among African Americans (thus requiring greater deterrence), but this does not seem to be the case when it comes to drugs (also see the 2013 American Civil Liberties Union report on this topic).

Drug use of high school seniors by race, 1980, 1993, 2009

| 1980 | 1993 | 2009 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| White (cocaine) | 5.4% | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Black (cocaine) | 2.0 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| White (marijuana) | 34.2 | 16.7 | 21.2 |

| Black (marijuana) | 26.5 | 10.8 | 20.6 |

Source: Author's calculation of National Center for Health Statistics (2013)

Drug arrests by race, 1980, 1993, and 2009

| 1980 | 1993 | 2009 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| White (possession) | 182.1 | 236.9 | 367.3 |

| Black (possession) | 341 | 843 | 1039.6 |

| White (sale) | 43.7 | 75.2 | 72.5 |

| Black (sale) | 163.9 | 507.8 | 311.6 |

Source: Author's calculation from Snyder (2011)

Percentage change in the proportion of offenses committed by blacks and whites serving time in state prison, by offense type, 1986–1999

| Offenses | Black | White |

|---|---|---|

| Murder | 7 | 24 |

| Manslaughter | -14 | -14 |

| Rape | -23 | 6 |

| Other sexual assault | 7 | -20 |

| Robbery | 3 | -43 |

| Assault | -6 | -33 |

| Burglary | -2 | -21 |

| Larceny | -1 | -8 |

| Motor vehicle theft | 1 | -34 |

| Fraud | 27 | 2 |

| Drug offenses | 48 | -62 |

Source: Author's calculation from Beck and Harrison (2001) and U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics (1989)

An anecdotal example10 of discriminatory enforcement of drug policies with regard to the black community can be found in the case of Hearn, Texas. The local drug task force conducted annual drug raids in low-income black neighborhoods based on unreliable, and sometimes forced, statements of confidential informants and fabricated evidence for 15 years. When time came each year to conduct raids, law enforcement officials would candidly joke about the raids, stating that “ it was ‘time to round up the niggers,’ and laughed about watching African Americans run in fear during the sweeps” (Kelly v. Paschall 2003, 28). Many of the victims of these raids were arrested and detained. In one invasion, the drug task force arrested 15 percent of the young black men within a community. In addition, some victims pleaded guilty to reduced charges instead of risking a trial of mostly all white jurors and longer prison terms, which is a valid concern given that the likelihood of conviction for blacks could increase by 16 percentage points when juries are created from entirely white jury pools (Anwar, Bayer, and Hjalmarsson 2012).

A recent report investigating the determinants of wrongful convictions found a lying non-eyewitness to significantly increase the likelihood of a wrongful conviction (Gould et al. 2013). This last point is also important because the mandatory minimum legislation for federal drug crimes allows for the defendant to avoid what could be a lengthy sentence if he or she provides “substantial assistance” in the prosecution of other individuals (Blumenson and Nilsen 1998). Thus, not only has the drug war imprisoned nonviolent offenders at alarming rates, but it is also reasonable to conclude that it has brought about an increase in wrongful convictions and imprisonment.

As mentioned previously, the merits of racial profiling depend on whether or not it improves the efficiency of law enforcement. However, Harcourt (2004) argues that racial profiling is only justifiable if: 1) it leads to reductions in crime in the long run, 2) it improves the efficient provision of police resources, and 3) it does not bring about a ratchet effect.11 Biased policing is likely to fail conditions one and three because it is probable that black criminal behavior is less responsive to changes in policing due to inferior employment prospects for blacks, and because it is likely that racial profiling will lead to responses by law enforcement above and beyond what is necessary to affect criminal behavior (due to the nation’s history of racism). Even if racial profiling were to satisfy all of these conditions, there are still grounds to contest its use based on the historical and institutionalized oppression of African Americans and the need to achieve racial parity within the penal system (Harcourt 2004).

The second type of discretion contributing to racial inequities in the criminal justice system is prosecutorial decisions. Prosecutors are often overlooked for the role they play in racial disparities within the penal system. Like police officers, they have substantial authorization in determining the final outcome of a case as they have the freedom to pursue, drop, or adjust criminal charges (A.J. Davis 1998; Rehavi and Starr 2012). New empirical evidence suggests that a significant portion of the unexplained sentencing gap between blacks and whites can be explained by initial charges submitted by the prosecuting attorney. In particular, prosecutors are roughly two times as likely to charge a black defendant with a crime that falls under the mandatory minimum versus a comparable white defendant (Rehavi and Starr 2012). This may explain why racial biases in sentencing persisted (Mustard 2001) even after the enactment of determinate sentencing.

Cole (2001) suggests that such inequality within the criminal justice system is necessary in order to balance the trade-off between protecting constitutional rights and guarding against criminal activity. In other words, in order for society to obtain greater civil liberties, society must be willing to tolerate greater levels of crime. As a result, the criminal justice system depends on unequal administration of the law (based on race and class) in order to maintain the constitutional rights of the more privileged. Persson and Siven (2007) develop a general equilibrium model of the judicial process and theoretically come to a similar conclusion. Within their framework, the median voter will choose a punishment as well as the willingness to let the guilty go free to avoid convicting the innocent (i.e., reasonable doubt). In other words, the median voter chooses the threshold of guilt. Within this framework, the courts determine if the evidence presented is above this cutoff; if so the individual is convicted of the crime. The greater the bar, the more convincing the evidence must be to obtain a conviction. The authors find that society is tolerant of crime because there is a “hardened,” unbearable group of criminals in society that makes it possible for an innocent person to be mistaken for a criminal. Since a white person could not be mistaken for black, and since blacks are cast as society’s “hardened,” unbearable, group of criminals, mainstream American can afford to be more punitive.

Much like Cole (2001), the theoretical results from Persson and Siven (2007) imply that society does not have to make the trade-off between greater tolerance (rights) in the judicial process when it is not possible for the majority to be mistaken as the deviant group. Moreover, the existence of race, and the assignment to the status of criminal based on race, allows society to enact a different burden of proof for different races. Specifically, the burden of proof for a conviction is low for minorities but high for whites; thus, creating two criminal justice systems under the façade that all persons are equal under the law, and thereby avoiding the required exchange between civil liberties and tolerance of crime. This alone could cause rational prosecutors (who are not necessarily driven by racial bias but who are seeking to maximize convictions), for example, to be stricter on blacks than whites.

Criminal behavior

Undoubtedly, many might purport that the excessive increase in the incarceration rate of black males is due to a greater propensity to commit crime. Nonetheless, Raphael and Stoll (2009, 2013) provide convincing evidence that society is responsible (through our public policy choices) for the hyperincarceration of black men; they find very little changes in criminal behavior. This does not negate the fact that some of the historical disproportionate incarceration rates between African Americans and whites might be due to differences in criminal behavior. However, various studies suggest that it is wrong to view this behavior as anything more than a symptom of historical barriers to social assimilation. In particular, Grogger (1991) finds that blacks’ criminal behavior more closely resembles the economic model of crime. One conclusion that can be drawn from this finding is that labor market opportunities (i.e., employment opportunities and wages) will lower blacks’ decision to participate in criminal activity. Since blacks have historically faced barriers to entry into the labor market (Darity and Mason 1998) and have historically experienced exorbitant rates of unemployment (Cox 2010), it is not surprising that barriers to human capital investment and lack of employment options might lead to increased participation in criminal activity (Evans, Garthwaite, and Moore 2012; Gyimah-Brempong and Price 2006; Grogger 1992; Grogger 1998).

Other research has found that more education (Lochner and Moretti 2004), lower unemployment (Myers 1983, Raphael and Winter-Ebmer 2001; Mustard 2010), and higher low-skill wages (Gould, Weinberg, and Mustard 2002; Mustard 2010) would reduce criminal activity, but income inequality increases violent crime (Kelly 2000; Fajnzylber, Lederman, Loayza 2002). For example, Deming (2011) finds that allowing access to better schools (as measured by peer and teacher quality) actually reduces future criminal participation of high-risk youth. Estimates that I calculated for the Alliance for Excellent Education (2013) suggests that increasing the average freshman high school graduation rate (AFGR) by 5 percentage points would lead to 18.5 billion in annual crime-related savings.

Finally, as discussed previously, contact with the criminal justice system can lead to inferior labor market opportunities and can cause increased criminal behavior (Bailey 2014; Bayer, Hjalmarsson, and Pozen 2009; Chen and Shapiro 2007; Grogger 1998). In fact, findings by Donohue and Siegelman (1998) suggest that if society redirected money spent on incarceration towards social programs (e.g., early childhood education and other types of programs aimed at increasing education and earnings), and if these programs were targeted towards the most at-risk youth (i.e., black youth), then this would be just as effective, if not more, at abating crime as increasing the prison population. According to my own calculations, increasing the national black male average freshman high school graduation rate to the white male average would lead to yearly savings of $31.3 billion in crime. Thus, even if we view hyperincarceration from a behavioral perspective we are reminded of the social costs of choosing chaos over community building (i.e., refusing to invest in true social justice).

Where do we go from here, to chaos or community?

King (1968/2010) urged the country to build community by mending race relations. However, it is evident from the mass incarceration policies implemented over the past 40 years that society has to this point chosen chaos (resulting in the hyperincarceration of African Americans) over community building (restoration of the black community). The collateral consequences of these policies have been devastating to the black community and they include heightened health disparities, destruction of the black family, increased barriers to employment and human capital investment resulting in increases in racial economic inequality, and a loss of citizenship status and political power through felon disenfranchisement laws (see Western and Pettit 2005; Holzer, Offner, and Sorensen 2005; Holzer, Raphael, and Stoll 2006; Holzer, Raphael, and Stoll 2004; Western and Pettit 2000; Travis 2002; Chandra 2003; Western 2007; Charles and Luoh 2010; Pager, Western, and Suggie 2009; Lopoo and Western 2005; Western and Wildeman 2008; Uggen, Manza, and Thompson 2006; Pinard 2010; Johnson and Raphael 2009; Lee and Wildeman 2011; Cox 2012; Cox and Wallace 2013). For example, Johnson and Raphael (2009) find that male incarceration explains the majority of the disparity in AIDS rates between black and white women and Cox and Wallace (2013) find that the shock of an incarceration increases the likelihood that households with children will experience food insecurity.

Although the right for blacks to vote has been enforced since the Voting Rights Act of 1965, mass incarceration policies have effectively taken this entitlement away from numerous African Americans. So extensive is the hyperincarceration crisis that it is estimated that had it not been for felon disenfranchisement laws, Al Gore would have won Florida by 31,000 votes in the 2000 presidential election (Karlan 2008). Although some progress has been made, it is evident that many blacks are confronted with the same obstacles King so fervently fought against during the civil rights movement. We must again ask ourselves: Where do we go from here? Are we going to continue down a road of chaos or are we going to work to build a truly inclusive society?

As King (1968/2010) suggested, the first step in genuinely constructing a real community is coming to terms with the fact that we are a racist nation. In fact, he suggested that whites put forth effort to “…reeducate themselves out of their racial ignorance” (King, 1968/2010, 243). However, this never happened on a national scale. We have yet to have a nationwide dialogue about race and the consequences of racism. In fact, instead of acknowledging our long-documented history of oppression and the institutionalization of this discrimination, society continues to fall into the trap that has become the legacy of the Moynihan report: preferring to believe that African Americans are responsible for the obstacles they face since, it is thought, they belong to a defiant culture. Up to this point, society would much rather avoid race relations, believing the pretense that we are a progressive nation that has left its racist, violent history in the past. However, our criminal justice system tells the true story of our nation and the real progress we have made. It continues to tell a story of the oppression and subjugation of people of color and the poor, and the implicit racial bias that remains in the soul of America. Community building starts with the confession that we are a racist nation. Once we can admit and openly discuss our sins, we can start the process of healing.

While this may sound cliché, I am convinced there is no other way. Although it is true that policies resulted in mass incarceration, it is the systemic racial bias within the law that allowed these policies to continue as long as they have, leading to the disproportionate incarceration of African Americans. Had these laws been enforced equally in all communities, it is unlikely the nation would have been so tolerant of mass incarceration policies. Society’s inherent beliefs about the inferiority and deviousness of African Americans have led to a dual system of justice: one for whites and another for blacks and other minorities, a system that many communities within the United States attempted to profit from. Taken from this point of view, the penal system could be viewed as an extension of chattel slavery, requiring an abolitionist approach “…to drastically reduce the prison population by seeking state and federal moratoriums on new prison constructions, amnesty for most prisoners convicted of nonviolent crimes, and repeal of excessive mandatory sentences for drug offenses” (Roberts 2008). We should also look to Portugal’s example and investigate the option of decriminalizing drugs (especially since this seems to have been a successful strategy). Moreover, there needs to be a greater social push to increase the diversity of criminal justice actors with the most discretion: police officers, prosecutors, and judges. This could be done, for example, through educational loan repayment programs or scholarships for individuals who want to enter public service through the criminal justice sector.

Finally, for decades politicians have advocated for policies that affect the poor in general with the belief that the benefits would trickle down to the black community. However, previously presented evidence suggests that redirecting money used to expand incarceration towards social programs that improve the quality of education, and enhance the job skills and employment specifically of marginalized youth (e.g., poor black youth) would not only lead to a decline in income inequality, but would also reduce crime as much as policies to expand incarceration, if not more.

One example of a program that could achieve this is the federal job guarantee put forth by Darity and Hamilton (2012), which they call the National Investment Employment Corps. This program would not only help to improve employment and earnings of high-risk youth, but would also help to lower crime (according to the findings by Grogger 1991) especially if targeted towards black youth, who suffer from extremely high unemployment rates. One might initially write this program off as politically infeasible, but society is already spending extraordinary amounts of money to sustain individuals in prison: Average costs per inmate are estimated to be $31,282 in the United States (Henrichson and Delaney 2012). Darity and Hamilton (2012) propose a mean salary of $40,000, and although this figure is roughly $9,000 more than the direct costs to house an inmate, these costs do not include indirect costs such as the costs of crime to the victim, and the costs of incarceration to families and the community.

Moreover, we are already employing and providing education and job skills training to individuals imprisoned because most state department of corrections also have a charge to rehabilitate. Why not offer these programs on the front end (prior to committing a crime), instead of after it is too late? We must ask ourselves why we are willing to make these investments while these individuals are incarcerated, but are not willing to invest in these same individuals prior to their admission to prison. It is time for society to make the difficult choice that it has been avoiding since the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965: to wholeheartedly invest in the black community in order to achieve the social and economic equality Martin Luther King Jr. dreamed of over 51 years ago.

About the author

Robynn Cox is an assistant professor in the Economics Department at Spelman College and a RCMAR Scholar at the USC Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics. Her research investigates the economic and social consequences of mass incarceration, and its effect on racial inequality.

Endnotes

1. Please see Cox (2012) for a discussion of the growth in the incarceration of women.

2. In 1971 Nixon officially began the war on drugs and declared drugs “public enemy number 1.” The Nixon era was the only period in which most of the funding was allocated toward treatment rather than law enforcement (Frontline 2012).

3. Note that drug offenses led to a large increase in admissions for both state and federal facilities, but drug admissions played different roles in influencing the incarceration rate for federal and state facilities (see Raphael and Stoll 2013).

4. Note that simple assault is typically classified with aggravated assault in prison data.

5. This is in part a statistical discrimination argument in which employers might associate the likelihood of being arrested and therefore absent from work with race and thus choose not to hire/promote African Americans to positions where absenteeism is costly. It may also be the case that employers actually observe higher absenteeism rates among blacks than whites due to higher relative arrests rates, leading blacks to be forced into secondary labor markets where absenteeism is not as costly.

6. I would like to thank Sarah Jacobson for helping me to formulate this thought.

7. It should be noted that the data used in many of the studies were collected after racial profiling received national attention and following the passage of the Traffic Stops Statistic Act of 1997. Therefore, to the extent that officers had a behavioral response to greater inspection of their actions, it is reasonable to believe that the data would not be representative of traffic stops prior to such data collection, and, therefore, that the results would be biased towards finding no preference-based discrimination.

8. Donohue and Levitt (2001) conducted one of the first empirical studies to investigate whether the race of police matters. They find that white officers monitor minorities at greater rates, and minority officers significantly increase the rate of enforcement on whites but have no effect on the enforcement of non-whites. However, they called for more research to determine the significance of their results. Antonovics and Knight (2009) and Close and Mason (2006 and 2007) developed models based on the notion that if policing is solely the result of statistical discrimination the race of the police officer should not be important. Both studies find evidence that the race of the police officer matters in determining intergroup (e.g., white, black, etc.) policing, suggesting the presence of preference-based racial profiling.

9. Note that substance use in high school is a strong predictor of future substance abuse (Merline et al. 2004).

10. For additional examples please see Russell (1998).

11. Harcourt (2004) defines the ratchet effect as one where racial profiling creates a situation where the proportion of the supervised population of the profiled group is larger than the proportion of the crimes they are committing.

References

Acs, G., Braswell, K., Sorensen, E., and Turner, M.A. 2013. The Moynihan Report Revisited. Urban Institute.

Alexander, M. 2010. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: The New Press.

Alliance for Excellent Education. 2013. Saving Future, Saving Dollars: the Impact of Education on Crime Reduction and Earnings. http://all4ed.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/SavingFutures.pdf.

American Civil Liberties Union. 2013. The War on Marijuana in Black and White. https://www.aclu.org/files/assets/aclu-thewaronmarijuana-rel2.pdf.

Andreozzi, L. 2004. “Rewarding Policemen Increases Crime. Another Surprising Result from the Inspection Game.” Public Choice, 121(1-2), 69–82.

Antonovics, K., and Knight, B.G. 2009. “A New Look at Racial Profiling: Evidence from the Boston Police Department.” Review of Economics and Statistics, 91(1), 163-177.

Anwar, S., Bayer, P., and Hjalmarsson, R. 2012. “The Impact of Jury Race in Criminal Trials.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(2), 1017-1055.

Bailey, L. A. 2014. “The Glass Ceiling and Relative Arrest Rates of Blacks Compared to Whites.” The Review of Black Political Economy, 41(4), 411–432.

Bayer, P., Hjalmarsson, R., and Pozen, D. 2009. “Building Criminal Capital Behind Bars: Peer Effects in Juvenile Corrections.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(1), 105–147.

Beck, A. J., and Harrison, P. M. 2001. Prisoners in 2000. Bureau of Justice Statistics. http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=927.

Benson, B.L., and Rasmussen, D. W. 1996. “Predatory Public Finance and the Origins of the War on Drugs 1984-1989.” The Independent Review, 1(2), 163-189.

Benson, B.L., Kim, I., and Rasmussen, D. 1994. “Estimating Deterrence Effects: A Public Choice Perspective on the Economics of Crime Literature.” Southern Economic Journal, 61(1), 161-168.

Blumenson, E., and Nilsen, E. 1998. “Policing for Profit: The Drug War’s Hidden Economic Agenda.” The University of Chicago Law Review, 35-114.

Bonczar, T. P. 2003. Prevalence of Imprisonment in the U.S. Population 1974-2001. http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/piusp01.pdf.

Brown, J.M., Gilliard, D. K., Snell, T. L., Stephan, J. J., and Wilson, D. J. 1996. Correctional Populations in the United States, 1994. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpius94.pdf.

Carson, E. Ann, and Mulako-Wangota, Joseph. 2013. Bureau of Justice Statistics. (“Imprisonment Rates of Custody Population – Sentences Greater than 1 Year”). Generated using the Corrections Statistical Analysis Tool (CSAT)-Prisoners at www.bjs.gov. August 1

Chandra, Amitabh. 2003. Is the Convergence in the Racial Wage Gap Illusory? National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 9476.

Charles, K.K., and Luoh, M.C. 2010. “Male Incarceration, the Marriage Market, and Female Outcomes.” The Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(3), 614-627.

Chen, M. K., and Shapiro, Jesse M. 2007. “Do Harsher Prison Conditions Reduce Recidivism? A Discontinuity-based Approach.” American Law and Economics Review 9(1), 1-30.

Cheung, A. 2002 (updated 2004). Prison Privatization and the Use of Incarceration. The Sentencing Project. http://www.sentencingproject.org/doc/publications/inc_prisonprivatization.pdf.

Close, Billy R., and Mason, Patrick L. 2006. “After the Traffic Stops: Officer Characteristics and Enforcement Actions.” B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy: Topics in Economic Analysis and Policy, 6(1), 1-41.

Close, B.R., and Mason, P.L. 2007. “Searching for Efficient Enforcement: Officer Characteristics and Racially Biased Policing.” Review of Law and Economics, 3(2), pp. 363-321. http://www.bepress.com/rle/vol3/iss2/art5.

Cole, D. 2001. “No Equal Justice.” Connecticut Public Interest Law Journal, 1(1), 19-33.

Correll, J., Park, B., Judd, C. M., and Wittenbrink, B. 2007. “The Influence of Stereotypes on Decisions to Shoot.” European Journal of Social Psychology, 37(6), 1102-1117.

Cox, R. 2010. “Crime, Incarceration, and Employment in Light of the Great Recession.” The Review of Black Political Economy, 37(3-4), 283-294.

Cox, R. J. 2012. “The Impact of Mass Incarceration on the Lives of African American Women.” The Review of Black Political Economy, 39(2), 203-212.

Cox, R., and Wallace, S. 2013. The Impact of Incarceration on Food Insecurity Among Households with Children. Andrew Young School of Policy Studies Research Paper Series No. 13-05. http://ssrn.com/abstract=2212909 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2212909

Crenshaw, K.W. 1998. “Color Blindness, History, and the Law.” In The House that Race Built: Original Essays by Toni Morrison, Angela Y. Davis, Cornel West, and Others on Black Americans and Politics in America Today, Lubiano, W. , ed., 280-288, New York: Random House.

Darity, W. A., and Mason, P. L. 1998. “Evidence on Discrimination in Employment: Codes of Color, Codes of Gender.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 12(2), 63-90.

Darity Jr, W., and Hamilton, D. 2012. “Bold Policies for Economic Justice.” The Review of Black Political Economy, 39(1), 79-85.

Davis, A. J. 1998. “Prosecution and Race: The Power and Privilege of Discretion.” Fordham Law Review, 67(13).

Davis, A.Y. 1998. “Black Americans and the Punishment Industry.” In The House that Race Built: Original Essays by Toni Morrison, Angela Y. Davis, Cornel West, and Others on Black Americans and Politics in America Today, Lubiano, W. , ed., 264-279, New York: Random House.

Deming, D. J. 2011. “Better Schools, Less Crime?” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(4), 2063-2115.

Donohue, J., and Levitt, S. 2001. “The Impact of Race on Policing and Arrests.” Journal of Law and Economics, 44, 367-394.

Donohue III, J. J., and Siegelman, P. 1998. “Allocating Resources Among Prisons and Social Programs in the Battle Against Crime.” The Journal of Legal Studies, 27(1), 1-43.

Dixon, T. L., and Maddox, K. B. 2005. “Skin Tone, Crime News, and Social Reality Judgments: Priming the Stereotype of the Dark and Dangerous Black Criminal.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 35(8), 1555-1570.

Eberhardt, J. L., Goff, P. A., Purdie, V. J., and Davies, P. G. 2004. “Seeing Black: Race, Crime, and Visual Processing.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(6), 876.

Evans, W. N., Garthwaite, C., and Moore, T. J. 2012. The White/Black Educational Gap, Stalled Progress, and the Long Term Consequences of the Emergence of Crack Cocaine Markets. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 18437.

Fajnzylber, P., Lederman, D., and Loayza, N. 2002. “Inequality and Violent Crime.” Journal of Law and Economics, XLV, 1-40.

Farrigan, Tracey L, and Amy K. Glasmeier. 2007. “The Economic Impacts of the Prison Development Boom on Persistently Poor Rural Places.” International Regional Science Review, 30(3), 274-299.

Fredrickson, G. M. 1971. The Black Image in the White Mind: The Debate on Afro-American Character and Destiny, 1817–1914. New York: Harper & Row.

Frontline. 2012. Thirty Years of America’s Drug War. Public Broadcasting Station. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/drugs/cron/.

Gibson, C., and Jung, K. 2002. “Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals By Race, 1790 to 1990, and By Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, For The United States, Regions, Divisions, and States.” U.S. Census Bureau. http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0056/twps0056.html#sou

Gould, J.B., Carrano, J., Leo, R., and Young, J. 2013. Predicting and Preventing Wrongful Convictions. https://ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/241389.pdf.

Gould, S. J. 1996. The Mismeasure of Man. New York: WW Norton & Company.

Gould, E. D., Weinberg, B. A., and Mustard, D. B. 2002. “Crime Rates and Local Labor Market Opportunities in the United States: 1979–1997.” Review of Economics and Statistics, 84(1), 45-61.

Government Accountability Office. 1993. War on Drugs: Federal Assistance to State and Local Drug Enforcement. http://www.gao.gov/assets/220/217895.pdf.

Graham, S., and Lowery, B.S. 2004. “Priming Unconscious Racial Stereotypes about Adolescent Offenders.” Law and Human Behavior, 28(5), 483-504.

Grogger, J. 1991. “Certainty vs. Severity of Punishment.” Economic Inquiry, Vol. 29 (2), 297-310.

Grogger, J. 1992. “Arrests, Persistent Youth Joblessness, and Black/White Employment Differentials.” The Review of Economics and Statistics, 74(1), 100-106.

Grogger, J. 1998. “Market Wages and Youth Crime.” Journal of Labor Economics, 16(4), 756-791.

Guerino, P., Harrison, P. M., and Sabol, W. J. 2011. Prisoners in 2010. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=2230.

Gyimah-Brempong, K., and Price, G.N. 2006. “Crime and Punishment: and Skin Hue Too?” AEA Papers and Proceedings, 96(2), 246-250.

Harcourt, B. E. 2004. “Rethinking Racial Profiling: A Critique of the Economics, Civil Liberties, and Constitutional Literature, and of Criminal Profiling More Generally.” The University of Chicago Law Review, 1275-1381.

Henrichson, C., and Delaney, R. 2012. “The Price of Prisons: What Incarceration Costs Taxpayers.” Federal Sentencing Reporter, 25(1), 68-80.

Holzer, H. 2009. “Collateral Costs: Effects of Incarceration on Employment and Earnings Among Young Workers.” in Do Prisons Make Us Safer? The Benefits and Costs of the Prison Boom, Steven Raphael and Michael A. Stoll, eds., 239-65. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Holzer, H. J., Offner, P., and Sorensen, E. 2005. “Declining Employment among Young Black Less-educated Men: The Role of Incarceration and Child Support.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 24 (2), 329–250.

Holzer, H. J., Raphael, S., and Stoll, M. A. 2004. “How Willing are Employers to Hire Ex-Offenders?” Focus, 23(2), 40-43.

Holzer, H., Raphael, S., and Stoll, M. 2006. “Perceived Criminality, Criminal Background Checks, and the Racial Hiring Practices of Employers.” Journal of Law and Economics, vol. XLIX, pp. 451-480.

Hurwitz, J., and Peffley, M. 2005. “Playing the Race Card in the Post–Willie Horton Era: The Impact of Racialized Code Words on Support for Punitive Crime Policy.” Public Opinion Quarterly, 69(1), 99-112.

Johnson, R. C., and Raphael, S. 2009. “The Effects of Male Incarceration Dynamics on Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome Infection Rates among African American Women and Men.” Journal of Law and Economics, 52(2), 251-293.

Karlan, P. 2008. In Race, Incarceration, and American Values, Loury, G.C., ed., 41-56, Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Kelly, M. 2000. “Inequality and Crime.” Review of Economics and Statistics, 82(4), 530-539.

Kelly v. Paschall, Texas Civ. 02-A-02-CA-702 JN (ACLU, 2003). http://www.aclu.org/FilesPDFs/2nd%20amended%20complaint%20in%20kelly%20v%20paschall.pdf.

King Jr., M. L. 2010. Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? [Kindle HD Version]. Retrieved from Amazon Books. (Original work published 1968).

Kirchhoff, S. M. 2010. Economic Impacts of Prison Growth. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service.

Lee, H., and Wildeman, C. 2011. “Things Fall Apart: Health Consequences of Mass Imprisonment for African American Women.” The Review of Black Political Economy, 1-14.

Lochner, L., and Moretti, E. 2004. “The Effect of Education on Crime: Evidence from Prison Inmates, Arrests, and Self-reports. The American Economic Review, 94 (1), 155-189.

Lopoo, L. M., and Western, B. 2005. “Incarceration and the Formation and Stability of Marital Unions.” Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(3), 721-734.

Loury, G. 2008. In Race, Incarceration, and American Values, Loury, G.C., ed., 57-70, Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Merline, Alicia C., Patrick M. O’Malley, John E. Schulenberg, Jerald G. Bachman, and Lloyd D. Johnston. 2004. “Substance Use Among Adults 35 Years of Age: Prevalence, Adulthood Predictors, and Impact of Adolescent Substance Use.” American Journal of Public Health, 94 (1), 96-102.

Minor-Harper, S. 1986. State and Federal Prisoners, 1925-1985. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=3581.

Myers, M. A. 1993. “Inequality and the Punishment of Minor Offenders in the Early 20th Century.” Law & Society Review, 27, 313.

Myers, S.L., Jr. 1983. “Estimating the Economic Model of Crime: Employment Versus Punishment Effects.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 98 (1), 157-166.

Myers, S. L., and Sabol, W. J. 1987. “Unemployment and Racial Differences in Imprisonment.” The Review of Black Political Economy, 16(1-2), 189-209.

Mustard, D.B. 2001. “Racial, Ethnic, and Gender Disparities in Sentencing: Evidence from the U.S. Federal Courts.” Journal of Law and Economics, vol. XLIV, pp. 285-314.

Mustard, D. 2010. “Labor Markets and Crime: New Evidence on an Old Puzzle.” In Handbook on the Economics of Crime, B.L. Benson and P.R. Zimmerman, eds., pp. 342-358, Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

National Center for Health Statistics, 2013. Health, United States, 2012: With Special Feature on Emergency Care. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/contents2012.htm#059.

Pager, Devah. 2003. “The Mark of a Criminal Record.” American Journal of Sociology, 108(5), 937-975.

Pager, D., Western, B., and Bonikowski, B. 2009. “Discrimination in a Low Wage Labor Market: a Field Experiment.” American Sociological Review, 74, 777-799.

Pager, D., Western, B., and Suggie, N. 2009. “Sequencing Disadvantage: Barriers to Employment Facing Young Black and White Men with Criminal Records.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 623, 195-213.

Payne, B. K., Shimizu, Y., and Jacoby, L. 2005. “Mental Control and Visual Illusions: Toward Explaining Race-biased Weapon Misidentifications.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41(1), 36-47.

Persson, M., and Siven, C. H. 2007. “The Becker Paradox and Type I Versus Type II Errors in the Economics of Crime. International Economic Review, 48(1), 211-233.

Pettit, B., and Western, B. 2004. “Mass Imprisonment and the Life Course: Race and Class Inequality in US Incarceration.” American Sociological Review, 69(2), 151-169.

Pinard, M. 2010. “Reflections and Perspectives on Reentry and Collateral Consequences.” The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 100(3), 1213-1224.

Raphael, S. 2006. “The Socioeconomic Status of Black Males: The Increasing Importance of Incarceration.” In Public Policy and the Income Distribution, Alan J. Auerbach, David Card, and John M. Quigley, eds., 319-358. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Raphael, S. 2014. The New Scarlet Letter? Negotiating the U.S. Labor Market with a Criminal Record. WE Upjohn Institute.

Raphael, S., and Stoll, M. A. 2009. “Why Are So Many Americans in Prison?” In Do Prisons Make Us Safer? Raphael, S. and Stoll, M.A., eds., 27-72, New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Raphael, S., and Stoll, M. A. 2013. Why are So Many Americans in Prison? New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Raphael, S. and Winter-Ebmer, R. 2001. “Identifying the Effect of Unemployment on Crime.” Journal of Law and Economics, 44(1), 259-283.

Rehavi, M. Marit, and Starr, Sonja. 2012. “Racial Disparity in Federal Criminal Charging and its Sentencing Consequences.” The University of Michigan Law School, Law & Economics Research, Empirical Legal Studies Center Paper (12-002).

Roberts, D.E. 2008. “Constructing a Criminal Justice System Free of Racial Bias: An Abolitionist Framework.” Columbia Human Rights Law Review, 39, 261-285.

Russell, K. K. 1998. “Driving While Black: Corollary Phenomena and Collateral Consequences.” Boston College Law Review, 40, 717.

Sandy, K. R. 2002. “Discrimination Inherent in America’s Drug War: Hidden Racism Revealed by Examining the Hysteria over Crack.” The Alabama Law Review, 54, 665.

Snyder, H. N. 2011. Arrest in the United States, 1980-2009. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Sommers, S. R., and Ellsworth, P. C. 2000. “Race in the Courtroom: Perceptions of Guilt and Dispositional Attributions.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(11), 1367-1379.

Steinberg, S. 1998. “The Liberal Retreat from Race During the Post-Civil Rights Era.” In The House that Race Built: Original Essays by Toni Morrison, Angela Y. Davis, Cornel West, and Others on Black Americans and Politics in America Today, Lubiano, W., ed., 13-48, New York: Random House.

The Sentencing Project. 2013. Felony Disenfranchisement Laws in the United States. http://www.sentencingproject.org/detail/publication.cfm?publication_id=15.

Tieger, J. H. 1971. “Police Discretion and Discriminatory Enforcement.” Duke Law Journal, 1971(4), 717-743.

Tonry, M. H. 1995. Malign Neglect: Race, Crime, and Punishment in America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Travis, J. 2002. “Invisible Punishment: An Instrument of Social Exclusion.” In Invisible Punishment: The Collateral Consequences of Mass Imprisonment, Marc Mauer and Meda Chesney-Lind, eds., 15-36. New York: New Press.

Uggen C, Manza J, and Thompson, M. 2006. “Citizenship, Democracy, and the Civic Reintegration of Criminal Offenders.” Annals Of the American Academy Of Political and Social Sciences, 605, 281–310.