On July 24, in the third and final step of a minimum wage increase enacted by Congress in 2007, the federal minimum wage increased from $6.55 to $7.25, and an estimated 4.5 million of this country’s lowest paid workers got a much-needed raise. Over three-quarters — 3.4 million — of the affected workers were adults age 20 or older. The other 1.1 million workers were teenagers, age 16-19. Despite the relatively small number of affected teens, this nevertheless represents a large share, 19.9%, of all teen workers. (By comparison, only 2.7% of all workers age 20 and over were affected by the increase.)

Since the minimum wage was raised in July, the teen employment rate (the share of people age 16-19 who are employed) fell from 28.9% to 26.2%. Could this drop plausibly be attributed to July’s 70 cent increase in the minimum wage? A careful examination of the data finds no evidence to support that conclusion.

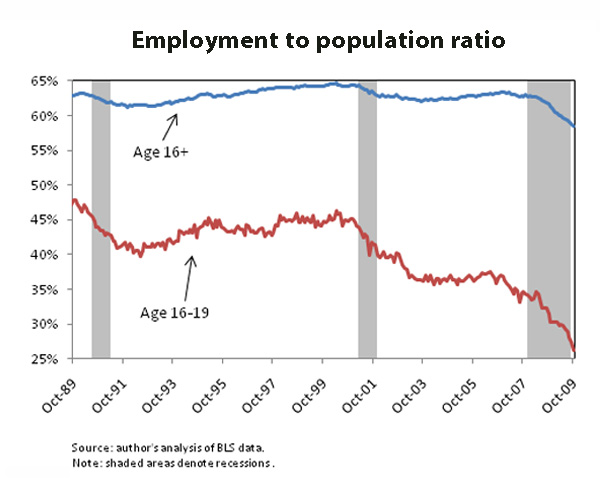

First, the labor market is in a severe downturn that is affecting essentially all groups. Since the recession started in December 2007, the overall employment rate has fallen from 62.7% to 58.5%, including a decline of 0.9 percentage points since July alone. Figure A shows the overall employment rate, along with the teen employment rate. Both the overall rate and the teen rate have experienced steep declines during the current downturn. The teen rate, however, has fallen farther, as the plot shows is always the case in recessions (recessions are shaded). Teen workers occupy the “last hired, first fired” rung on the job ladder, and their employment is hit much harder during downturns than that of older workers.

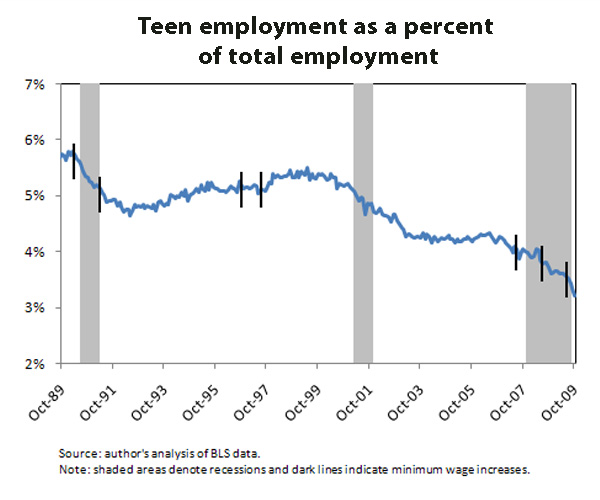

Figure B illustrates this further—it shows teen employment as a percent of total employment over time. Because teens are hit harder by downturns than older workers, their share of total employment drops during recessions (and, for the recessions of 1990 and 2001, during the period of joblessness that followed them). A quick examination of the plot reveals that far from being an aberration, the decline in the teen share of employment over the last two years is right in line with what would be expected given the length and severity of the current downturn in the labor market.

Instead, Figure B illustrates how teen employment is driven far more by larger labor market employment trends than by any effects of minimum wage changes. The black lines in Figure B mark times when Congress increased the minimum wage to keep up with inflation. The two-step increase in 1990 and 1991 occurred during a period of deterioration in the labor market, and the teen employment share dropped. The two-step increase in 1996 and 1997 occurred during a strong labor market, and the teen employment share increased. The three-step increase in 2007, 2008, and 2009 occurred during a weak labor market, and the teen employment share fell.

This observation is consistent with what careful empirical studies have found. While it is true that there is some disagreement among economists about whether increasing the minimum wage increases or decreases employment, there is a consensus on the essential point: the impact of a minimum wage raise on jobs, whether positive or negative, is small. The warnings of massive teen job loss due to minimum wage increases simply do not comport with the evidence.

What’s more, increasing the minimum wage benefits the economy. An analysis by the Economic Policy Institute, based on research by economists at the Federal Reserve Board of Chicago, found that July’s minimum wage increase would contribute $5.5 billion in spending over the 12 months following the increase, by getting additional income into the hands of workers who are likely to be struggling to make ends meet and therefore very likely to spend it. July’s minimum wage is providing excellent stimulus for the economy precisely when it needs it the most.

The disastrous economic events of the last two years underscore the need to restore a foundation for the U.S. economy where wages can again grow in tandem with productivity and workers are able to increase their living standards through increased earnings rather than through increased debt. July’s increase in the minimum wage, though far short in real terms of restoring the minimum wage to its high-water mark of the late 1960s, was nevertheless an important step in that direction.