Issue Brief #393

Introduction and executive summary

Last year was yet another year of poor wage growth for American workers. With few exceptions, real (inflation-adjusted) hourly wages fell or stagnated for workers across the wage spectrum between 2013 and 2014—even for those with a bachelor’s or advanced degree.

Of course, as EPI has documented for nearly three decades, this is not a new story. Comparing 2014 with 2007 (the last period of reasonable labor market health before the Great Recession), hourly wages for the vast majority of American workers have been flat or falling. And ever since 1979, the vast majority of American workers have seen their hourly wages stagnate or decline. This is despite real GDP growth of 149 percent and net productivity growth of 64 percent over this period. In short, the potential has existed for ample, broad-based wage growth over the last three-and-a-half decades, but these economic gains have largely bypassed the vast majority.

The poor performance of American workers’ wages in recent decades—particularly their failure to grow at anywhere near the pace of overall productivity—is the country’s central economic challenge. Raising wages is the key to addressing middle-class income stagnation, rising income inequality, and lagging economic mobility, and is essential to moving families out of poverty. EPI’s Raising America’s Pay initiative and the initiative’s overview paper (Bivens et al. 2014) explain in detail why raising wages is essential to improving Americans’ living standards.

Unfortunately, the gradually recovering economy has not translated into widespread wage gains over the last year. Though the labor market has continued to strengthen, it has not tightened nearly enough to absorb the millions of potential workers sidelined by the lack of job opportunities—and not nearly enough to generate real wage growth. Furthermore, growth in nominal wages (wages unadjusted for inflation) has failed to hit any reasonable target for the Federal Reserve to fear inflationary pressures and slow the economy by raising interest rates.

This paper details the most up-to-date wage trends through 2014, with special attention to what has happened since the last pre-recession labor market peak in 2007. Key findings include:

- From 2013 to 2014, real hourly wages fell at all wage levels, except for a miniscule 3 cent increase at the 40th percentile and a more significant increase at the 10th percentile.

- Wages grew at the 10th percentile because of minimum-wage increases in 2014 in states where 47.2 percent of U.S. workers reside. This illustrates that public policies can be an important tool for raising wages.

- Only those at the top of the wage distribution have real wages higher today than before the recession began.

- Across the distribution, men’s wages remain higher than women’s, but women have fared slightly better than men since 2007.

- Workers of color continue to have hourly wages far below those of their white counterparts. In 2014, the median black and median Hispanic wages were only about 75 percent and 70 percent, respectively, of the median white wage. All three groups have median wages in 2014 lower than in 2007.

- Looking at wages by educational attainment, the greatest real wage losses between 2013 and 2014 were among those with a college or advanced degree. This demonstrates that poor wage performance cannot be blamed on workers lacking adequate education or skills.

- Those with the least education actually saw a reversal in trend, likely related to the state-level minimum-wage increases.

- Despite wage declines in both 2013 and 2014, those with an advanced degree are the only ones who have returned to 2007 real wage levels.

- Nominal wage growth, by any measure, is far below wage growth consistent with the Federal Reserve Board’s 2 percent inflation target.

- There is no evidence of upward pressure on wages—let alone acceleration of wages—that would signal that the Federal Reserve Board should worry about incipient inflation and raise interest rates in an effort to slow the economy.

Real hourly wages stagnant or falling for most of the wage distribution

The rise in wage inequality (and income inequality for that matter) over the last three-and-a-half decades has been driven by a pronounced reduction in the collective and individual bargaining power of ordinary workers, for whom wages are the primary source of income (Bivens et al. 2014). It has been well-documented that hourly pay for the vast majority of American workers has diverged from economy-wide productivity, and this divergence is at the root of numerous American economic challenges (Mishel et al. 2012). Productivity has increased, providing the potential for wage gains. At the same time, workers’ ability to bargain for higher wages has eroded, leaving stagnant wages for the vast majority.

The latest data from 2014 reveal evidence of the same abysmal trends experienced through the Great Recession and much of the last three-and-a-half decades. Table 1 includes data from the 2007 peak and the two most recent years of data for comparison. Wages for the bottom 80 percent are no higher than in 2007, with modest gains at the top.

Hourly wages of all workers, by wage percentile, 2007–2014 (2014 dollars)

| 10th | 20th | 30th | 40th | 50th | 60th | 70th | 80th | 90th | 95th | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | $8.89 | $10.79 | $12.59 | $14.78 | $17.26 | $20.48 | $24.31 | $30.00 | $40.23 | $51.98 |

| 2013 | $8.51 | $10.15 | $12.14 | $14.43 | $16.97 | $20.07 | $24.27 | $30.30 | $41.11 | $53.67 |

| 2014 | $8.62 | $10.08 | $12.09 | $14.46 | $16.90 | $19.92 | $24.07 | $29.99 | $40.84 | $53.14 |

| Annualized percent change | ||||||||||

| 2007–2014 | -0.4% | -1.0% | -0.6% | -0.3% | -0.3% | -0.4% | -0.1% | 0.0% | 0.2% | 0.3% |

| 2013–2014 | 1.3% | -0.7% | -0.4% | 0.3% | -0.4% | -0.7% | -0.8% | -1.0% | -0.7% | -1.0% |

Note: The xth-percentile wage is the wage at which x% of wage earners earn less and (100-x)% earn more.

Source: EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata

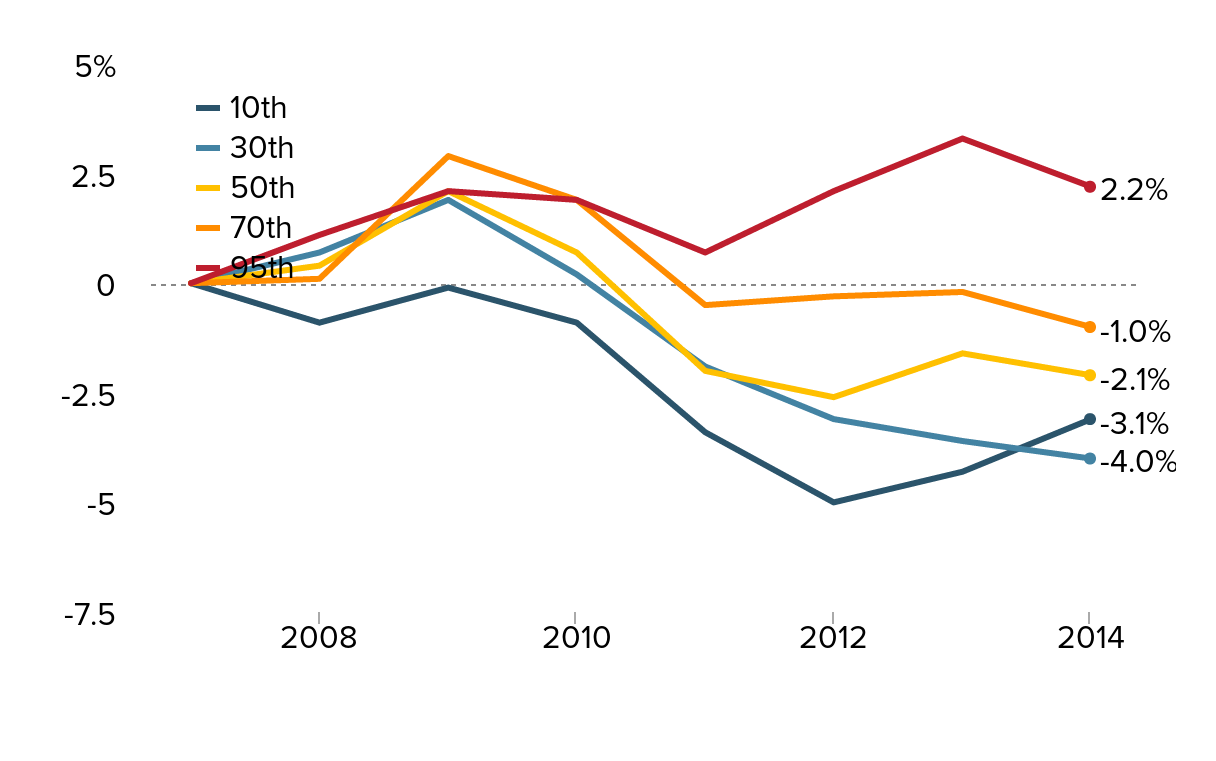

Cumulative percent change in real hourly wages, by wage percentile, 2007–2014

| Year | 10th | 30th | 50th | 70th | 95th |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 2008 | -0.9% | 0.7% | 0.4% | 0.1% | 1.1% |

| 2009 | -0.1% | 1.9% | 2.1% | 2.9% | 2.1% |

| 2010 | -0.9% | 0.2% | 0.7% | 1.9% | 1.9% |

| 2011 | -3.4% | -1.9% | -2.0% | -0.5% | 0.7% |

| 2012 | -5.0% | -3.1% | -2.6% | -0.3% | 2.1% |

| 2013 | -4.3% | -3.6% | -1.6% | -0.2% | 3.3% |

| 2014 | -3.1% | -4.0% | -2.1% | -1.0% | 2.2% |

Note: Sample based on all workers age 18–64. The xth-percentile wage is the wage at which x% of wage earners earn less and (100-x)% earn more.

Source: EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata

Figure A depicts some of the data presented in Table 1 by showing the cumulative change in real hourly wages for the 10th, 30th, 50th, 70th, and 95th percentiles between 2007 and 2014. After a sharp increase in real wages between 2008 and 2009, due primarily to negative inflation, wages for most groups fell through 2012. While there was an increase between 2012 and 2013, the increase was short-lived, and wages for most groups have fallen again over the last year. Wages for nearly all groups are lower in 2014 than they were at the end of the recession in 2009.

It is important to note that this fall in real wages over the last year was not accompanied by (or associated with) a significant jump in inflation. In fact, falling inflation over the last few months has led to an average inflation rate of only 1.6 percent between 2013 and 2014. Thus, the fall in real wages over the last year is clearly not driven by high inflation.

The impact of state minimum-wage increases

What is particularly striking about both Figure A and Table 1 is that almost every decile and the 95th percentile experienced real wage declines from 2013 to 2014, with two exceptions. First, there was a very small increase at the 40th percentile wage, up 3 cents, or 0.3 percent. A more economically significant increase occurred at the 10th percentile, up 11 cents, or 1.3 percent. This can be attributed to a series of state-level minimum-wage increases, which have been proven to lift wages, particularly at the bottom of the wage distribution.

Figure B displays in green the states with minimum-wage increases in 2014. Of these states, the largest increases were in those with legislated increases (California, Connecticut, Delaware, D.C., Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island). The remaining states in green had smaller increases resulting from indexing the minimum wage to inflation. Workers in states that increased their minimum wage in 2014 account for nearly half (47.2 percent) of the overall U.S. workforce.

States with minimum-wage increases in 2014

| State | Abbreviation | Category |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | AL | No change |

| Alaska | AK | No change |

| Arizona | AZ | Indexed |

| Arkansas | AR | No change |

| California | CA | Legislative |

| Colorado | CO | July |

| Connecticut | CT | Legislative |

| Delaware | DE | Legislative |

| District of Columbia | DC | July |

| Florida | FL | Indexed |

| Georgia | GA | No change |

| Hawaii | HI | No change |

| Idaho | ID | No change |

| Illinois | IL | No change |

| Indiana | IN | No change |

| Iowa | IA | No change |

| Kansas | KS | No change |

| Kentucky | KY | No change |

| Louisiana | LA | No change |

| Maine | ME | No change |

| Maryland | MD | No change |

| Massachusetts | MA | No change |

| Michigan | MI | Legislative |

| Minnesota | MN | August |

| Mississippi | MS | No change |

| Missouri | MO | Indexed |

| Montana | MT | Indexed |

| Nebraska | NE | No change |

| Nevada | NV | July |

| New Hampshire | NH | No change |

| New Jersey | NJ | Legislative |

| New Mexico | NM | No change |

| New York | NY | Legislative |

| North Carolina | NC | No change |

| North Dakota | ND | No change |

| Ohio | OH | Indexed |

| Oklahoma | OK | No change |

| Oregon | OR | Indexed |

| Pennsylvania | PA | No change |

| Rhode Island | RI | Legislative |

| South Carolina | SC | No change |

| South Dakota | SD | No change |

| Tennessee | TN | No change |

| Texas | TX | No change |

| Utah | UT | No change |

| Vermont | VT | Indexed |

| Virginia | VA | No change |

| Washington | WA | Indexed |

| West Virginia | WV | No change |

| Wisconsin | WI | No change |

| Wyoming | WY | No change |

Note: California, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island legislated minimum-wage increases. In the remaining states in green, the minimum wage increased due to indexing to inflation.

Source: EPI analysis of Cooper (2014) and NCSL (2014)

A state-by-state comparison of trends in the 10th percentile suggests that these minimum-wage increases account for the nationwide 10th percentile increase. Between 2013 and 2014, the 10th percentile wage in states with minimum-wage increases grew by an average of 1.6 percent, while it barely rose (a 0.3 percent increase) in states without a minimum-wage increase. That wages for most other deciles fell across both sets of states provides further evidence that the minimum-wage increases—not other factors—are driving the nationwide 10th percentile increase. This indicates that strong labor standards can improve outcomes even when the unemployment rate remains elevated and workers have severely reduced bargaining power.

Trends by gender and race/ethnicity

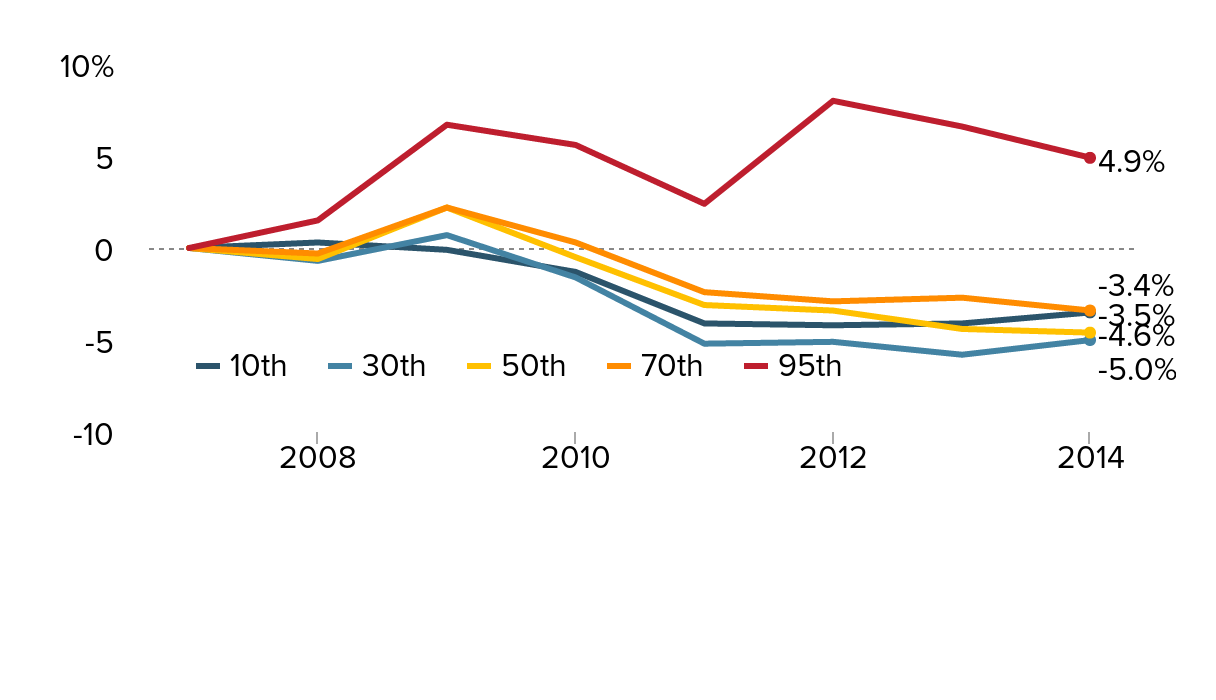

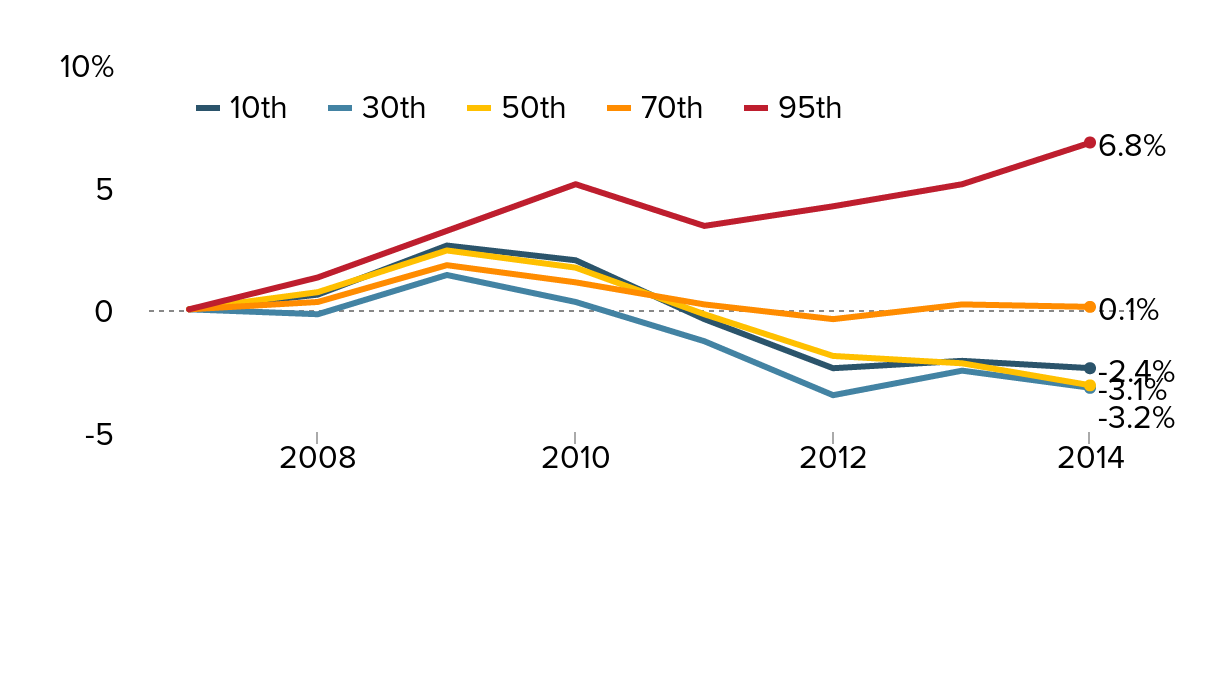

Even analyzing wages at different points in the wage distribution over time masks different outcomes between men and women and among various racial and ethnic subgroups. Table 2 replicates the analysis of wage deciles for men and women separately, with a comparison of gender wage disparities over 2007–2014. Figures C and D accompany this table, illustrating the cumulative percent change over 2007–2014 in real hourly wages of men and women at key wage levels. Long-term trends suggest that low- and middle-wage men have fared comparably poorly, and that wage gaps between the top and the middle, and between the top and the bottom, among both men and women have expanded continuously over the last three-and-a-half decades (Gould 2014).

Hourly wages of men and women, by wage percentile, 2007–2014 (2014 dollars)

| 10th | 20th | 30th | 40th | 50th | 60th | 70th | 80th | 90th | 95th | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | ||||||||||

| 2007 | $9.34 | $11.49 | $13.82 | $16.44 | $19.24 | $22.60 | $26.97 | $33.18 | $44.13 | $57.15 |

| 2013 | $8.96 | $10.56 | $13.02 | $15.44 | $18.41 | $21.82 | $26.24 | $33.02 | $45.76 | $60.92 |

| 2014 | $9.02 | $10.82 | $13.13 | $15.45 | $18.35 | $21.72 | $26.06 | $32.69 | $44.96 | $59.92 |

| Annualized percent change | ||||||||||

| 2007–2014 | -0.5% | -0.9% | -0.7% | -0.9% | -0.7% | -0.6% | -0.5% | -0.2% | 0.3% | 0.7% |

| 2013–2014 | 0.7% | 2.4% | 0.9% | 0.1% | -0.3% | -0.5% | -0.7% | -1.0% | -1.7% | -1.6% |

| Women | ||||||||||

| 2007 | $8.40 | $10.01 | $11.53 | $13.55 | $15.69 | $18.23 | $21.69 | $26.88 | $35.38 | $44.12 |

| 2013 | $8.22 | $9.73 | $11.24 | $13.21 | $15.35 | $18.24 | $21.74 | $27.04 | $36.27 | $46.37 |

| 2014 | $8.20 | $9.76 | $11.17 | $13.11 | $15.21 | $18.12 | $21.72 | $27.05 | $36.23 | $47.11 |

| Annualized percent change | ||||||||||

| 2007–2014 | -0.4% | -0.4% | -0.5% | -0.5% | -0.4% | -0.1% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.3% | 0.9% |

| 2013–2014 | -0.3% | 0.3% | -0.7% | -0.8% | -0.9% | -0.6% | -0.1% | 0.1% | -0.1% | 1.6% |

| Wage disparities (women/men) | ||||||||||

| 2007 | 89.9% | 87.2% | 83.5% | 82.4% | 81.5% | 80.7% | 80.4% | 81.0% | 80.2% | 77.2% |

| 2013 | 91.8% | 92.1% | 86.4% | 85.6% | 83.4% | 83.6% | 82.8% | 81.9% | 79.3% | 76.1% |

| 2014 | 90.9% | 90.2% | 85.0% | 84.9% | 82.9% | 83.4% | 83.3% | 82.7% | 80.6% | 78.6% |

Note: The xth-percentile wage is the wage at which x% of wage earners earn less and (100-x)% earn more.

Source: EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata

Cumulative percent change in real hourly wages of men, by wage percentile, 2007–2014

| Year | 10th | 30th | 50th | 70th | 95th |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 2008 | 0.3% | -0.7% | -0.6% | -0.3% | 1.5% |

| 2009 | -0.1% | 0.7% | 2.2% | 2.2% | 6.7% |

| 2010 | -1.3% | -1.6% | -0.5% | 0.3% | 5.6% |

| 2011 | -4.1% | -5.2% | -3.1% | -2.4% | 2.4% |

| 2012 | -4.2% | -5.1% | -3.4% | -2.9% | 8.0% |

| 2013 | -4.1% | -5.8% | -4.4% | -2.7% | 6.6% |

| 2014 | -3.5% | -5.0% | -4.6% | -3.4% | 4.9% |

Note: Sample based on all workers age 18–64. The xth-percentile wage is the wage at which x% of wage earners earn less and (100-x)% earn more.

Source: EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata

Cumulative percent change in real hourly wages of women, by wage percentile, 2007–2014

| Year | 10th | 30th | 50th | 70th | 95th |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 2008 | 0.6% | -0.2% | 0.7% | 0.3% | 1.3% |

| 2009 | 2.6% | 1.4% | 2.4% | 1.8% | 3.2% |

| 2010 | 2.0% | 0.3% | 1.7% | 1.1% | 5.1% |

| 2011 | -0.4% | -1.3% | -0.2% | 0.2% | 3.4% |

| 2012 | -2.4% | -3.5% | -1.9% | -0.4% | 4.2% |

| 2013 | -2.1% | -2.5% | -2.2% | 0.2% | 5.1% |

| 2014 | -2.4% | -3.2% | -3.1% | 0.1% | 6.8% |

Note: Sample based on all workers age 18–64. The xth-percentile wage is the wage at which x% of wage earners earn less and (100-x)% earn more.

Source: EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata

The wage trends since 2007 reflect this longer-term trend. Men’s wages fell over 2007–2014 for all but the top 10 percent of the wage distribution. Women fared slightly better; wages for the bottom 60 percent were lower in 2014 than in 2007. Hourly wages of women in 2014 still remain significantly below those of men. It is interesting to note that the women’s wage is a larger share of the men’s wage (i.e., the gender wage gap is smaller) at the 10th percentile than at the 95th (91 cents on the dollar versus only 79 cents).

Table 3 examines wage deciles for three race/ethnic subgroups: white non-Hispanics, black non-Hispanics, and Hispanics. As with the gender comparisons, the wage gaps between white workers and workers of color are much smaller at the bottom than at the middle or top of the wage distribution. At the middle, black workers are paid 75 cents for every dollar paid to whites, while Hispanic workers are paid even less (70 cents on the dollar). Furthermore, the black–white wage gap across most of the distribution appears to have increased modestly during the Great Recession and its aftermath.

Hourly wages by race/ethnicity and wage percentile, 2007–2014 (2014 dollars)

| 10th | 20th | 30th | 40th | 50th | 60th | 70th | 80th | 90th | 95th | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | ||||||||||

| 2007 | $9.20 | $11.43 | $13.73 | $16.25 | $19.01 | $21.97 | $26.29 | $32.26 | $42.92 | $54.76 |

| 2013 | $8.97 | $10.97 | $13.35 | $15.77 | $18.69 | $21.96 | $26.25 | $32.47 | $44.05 | $58.25 |

| 2014 | $8.98 | $10.99 | $13.46 | $15.79 | $18.70 | $21.94 | $26.17 | $32.22 | $43.49 | $57.40 |

| Annualized percent change | ||||||||||

| 2007–2014 | -0.3% | -0.6% | -0.3% | -0.4% | -0.2% | 0.0% | -0.1% | 0.0% | 0.2% | 0.7% |

| 2013–2014 | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.8% | 0.2% | 0.0% | -0.1% | -0.3% | -0.8% | -1.3% | -1.5% |

| Black | ||||||||||

| 2007 | $8.48 | $10.02 | $11.37 | $12.95 | $14.53 | $16.88 | $19.74 | $23.71 | $31.91 | $40.01 |

| 2013 | $8.14 | $9.39 | $10.54 | $12.26 | $14.32 | $16.33 | $19.17 | $23.88 | $31.74 | $40.78 |

| 2014 | $8.08 | $9.31 | $10.34 | $12.06 | $14.00 | $16.05 | $19.13 | $23.87 | $31.22 | $41.51 |

| Annualized percent change | ||||||||||

| 2007–2014 | -0.7% | -1.0% | -1.3% | -1.0% | -0.5% | -0.7% | -0.4% | 0.1% | -0.3% | 0.5% |

| 2013–2014 | -0.7% | -0.8% | -1.8% | -1.6% | -2.2% | -1.7% | -0.2% | 0.0% | -1.6% | 1.8% |

| Hispanic | ||||||||||

| 2007 | $8.21 | $9.22 | $10.42 | $11.56 | $13.44 | $15.18 | $17.60 | $21.72 | $28.81 | $38.01 |

| 2013 | $8.07 | $9.04 | $10.09 | $11.20 | $12.80 | $15.04 | $17.54 | $21.55 | $29.61 | $38.71 |

| 2014 | $8.10 | $9.14 | $10.06 | $11.46 | $13.01 | $15.04 | $17.73 | $21.60 | $29.85 | $38.46 |

| Annualized percent change | ||||||||||

| 2007–2014 | -0.2% | -0.1% | -0.5% | -0.1% | -0.5% | -0.1% | 0.1% | -0.1% | 0.5% | 0.2% |

| 2013–2014 | 0.5% | 1.1% | -0.3% | 2.3% | 1.7% | 0.0% | 1.1% | 0.3% | 0.8% | -0.6% |

| Wage disparities | ||||||||||

| Black as a share of white | ||||||||||

| 2007 | 92.1% | 87.7% | 82.8% | 79.7% | 76.4% | 76.8% | 75.1% | 73.5% | 74.3% | 73.1% |

| 2013 | 90.8% | 85.6% | 78.9% | 77.7% | 76.6% | 74.4% | 73.0% | 73.5% | 72.0% | 70.0% |

| 2014 | 90.0% | 84.8% | 76.8% | 76.4% | 74.8% | 73.1% | 73.1% | 74.1% | 71.8% | 72.3% |

| Hispanic as a share of white | ||||||||||

| 2007 | 89.2% | 80.7% | 75.9% | 71.1% | 70.7% | 69.1% | 67.0% | 67.3% | 67.1% | 69.4% |

| 2013 | 89.9% | 82.4% | 75.5% | 71.0% | 68.5% | 68.5% | 66.8% | 66.3% | 67.2% | 66.5% |

| 2014 | 90.2% | 83.1% | 74.7% | 72.6% | 69.6% | 68.5% | 67.7% | 67.0% | 68.6% | 67.0% |

Source: EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata

Among white workers, hourly wages rose since 2007 for only the top 10 percent. But, in the last year, wages rose slightly for the bottom 40 percent of white workers, while falling more substantially at the top. Between 2013 and 2014, black hourly wages fell most significantly at the median—a loss of 2.2 percent (32 cents). Among blacks, only the 95th percentile saw an increase over the last year. Although Hispanic wages are generally lower, they fared slightly better, with significant wage increases between 2013 and 2014 at the 20th, 40th, and 50th percentiles.

In short, regardless of gender or race/ethnicity, this analysis of deciles shows that wages have been stagnant at best over 2007–2014 and 2013–2014, with just a few exceptions. Indeed, all races and ethnicities and both genders have median wages in 2014 lower than in 2007.

Trends by education level

Next, we examine the most up-to-date hourly wage data by education attainment. A particularly prevalent story explains wage inequality as a simple consequence of growing employer demand for skills and education—often thought to be driven by advances in technology. According to this explanation, because there is a shortage of skilled or college-educated workers, the wage gap between workers with and without a college degree is widening. This is sometimes referred to as a “skill-biased technological change” explanation of wage inequality (since it is based on technology leading to the need for more skills). However, despite its great popularity and intuitive appeal, this story about recent wage trends being driven more and more by a race between education and technology does not fit the facts well, especially since the mid-1990s.

Table 4 presents the most recent data on average hourly wages by education for all workers and by gender. As with the aforementioned data on wage deciles, American workers fared poorly between 2013 and 2014. Here we find reinforcing evidence that a technologically related demand for more-credentialed workers has not persisted. The workers with the key credential—four-year college graduates—have not done that well, especially in the last year. In fact, among all education categories, the greatest real wage losses between 2013 and 2014 were among those with a college or advanced degree. Workers with a four-year college degree saw their hourly wages fall 1.3 percent from 2013 to 2014, while those with an advanced degree saw an hourly wage decline of 2.2 percent. In contrast, wages for those who did not complete high school actually rose slightly, by 0.6 percent—likely due to the state minimum-wage increases. Male workers experienced an even more pronounced version of the overall story, with greater gains at the bottom and larger losses at the top. At the same time, the wages of female workers with either an advanced degree or less than a high school diploma fell at about the same rate, with declines of 1.4 percent and 1.5 percent, respectively.

Average hourly wages by gender and education, 2007–2014 (2014 dollars)

| Less than high school | High school | Some college | College | Advanced degree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | |||||

| 2007 | $12.98 | $17.09 | $19.27 | $30.15 | $38.21 |

| 2013 | $12.24 | $16.46 | $18.16 | $29.94 | $39.06 |

| 2014 | $12.31 | $16.46 | $18.14 | $29.55 | $38.20 |

| Annualized percent change | |||||

| 2007–2014 | -0.8% | -0.5% | -0.9% | -0.3% | 0.0% |

| 2013–2014 | 0.6% | 0.0% | -0.1% | -1.3% | -2.2% |

| Men | |||||

| 2007 | $14.07 | $18.97 | $21.52 | $34.50 | $43.32 |

| 2013 | $13.17 | $18.08 | $20.25 | $34.26 | $45.31 |

| 2014 | $13.37 | $18.12 | $20.19 | $33.35 | $44.10 |

| Annualized percent change | |||||

| 2007–2014 | -0.7% | -0.7% | -0.9% | -0.5% | 0.3% |

| 2013–2014 | 1.5% | 0.2% | -0.3% | -2.7% | -2.7% |

| Women | |||||

| 2007 | $11.07 | $14.82 | $17.19 | $25.88 | $32.99 |

| 2013 | $10.60 | $14.39 | $16.21 | $25.77 | $33.27 |

| 2014 | $10.44 | $14.29 | $16.20 | $25.94 | $32.82 |

| Annualized percent change | |||||

| 2007–2014 | -0.8% | -0.5% | -0.8% | 0.0% | -0.1% |

| 2013–2014 | -1.5% | -0.7% | -0.1% | 0.6% | -1.4% |

| Wage disparities (women/men) | |||||

| 2007 | 78.7% | 78.1% | 79.9% | 75.0% | 76.1% |

| 2013 | 80.5% | 79.6% | 80.0% | 75.2% | 73.4% |

| 2014 | 78.1% | 78.9% | 80.2% | 77.8% | 74.4% |

Source: EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata

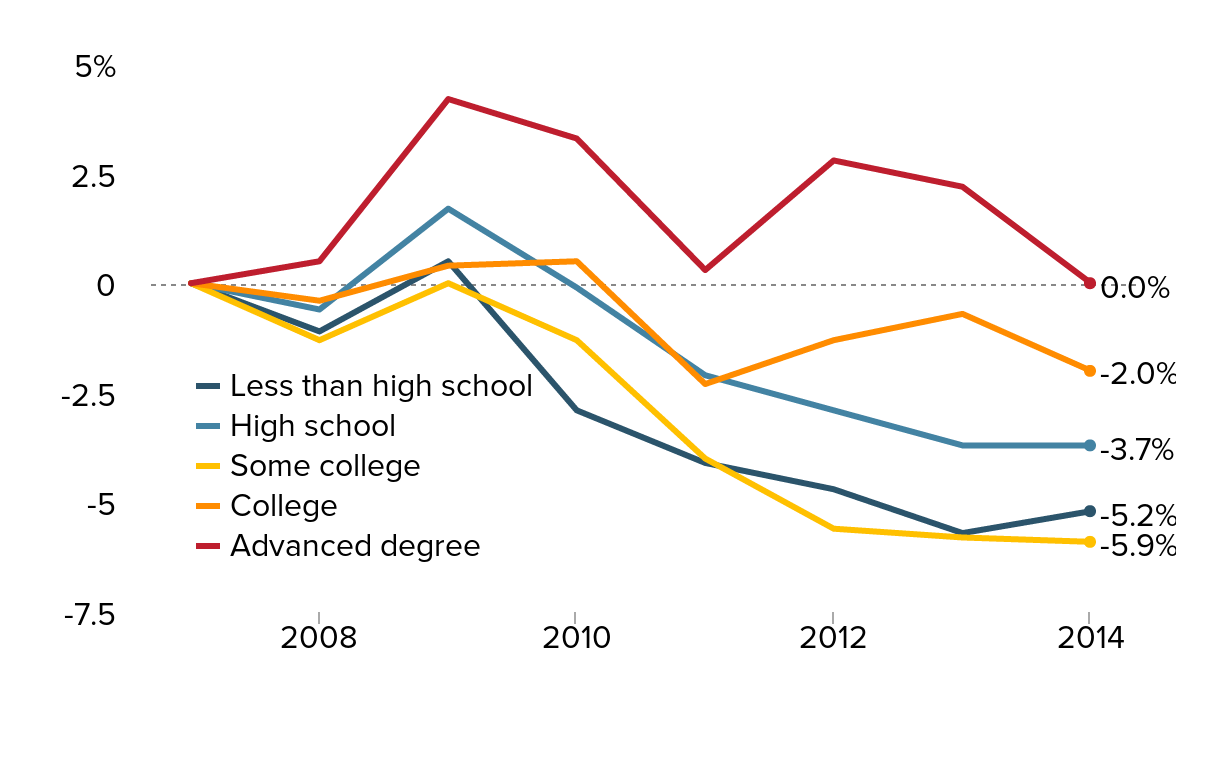

Figure E displays the cumulative percent change in real average hourly wages from 2007 to 2014 by education. It is clear that those in every education category experienced falling or stagnant wages since 2007. In fact, real hourly wages have declined for 90 percent of the workforce with four-year college degrees since 2007 (not shown). From 2000 to 2014, real wages of the 90th percentile of this group only increased 4.0 percent cumulatively.

Cumulative percent change in real average hourly wages, by education, 2007–2014

| Year | Less than high school | High school | Some college | College | Advanced degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 2008 | -1.1% | -0.6% | -1.3% | -0.4% | 0.5% |

| 2009 | 0.5% | 1.7% | 0.0% | 0.4% | 4.2% |

| 2010 | -2.9% | -0.1% | -1.3% | 0.5% | 3.3% |

| 2011 | -4.1% | -2.1% | -4.0% | -2.3% | 0.3% |

| 2012 | -4.7% | -2.9% | -5.6% | -1.3% | 2.8% |

| 2013 | -5.7% | -3.7% | -5.8% | -0.7% | 2.2% |

| 2014 | -5.2% | -3.7% | -5.9% | -2.0% | 0.0% |

Note: Sample based on all workers age 18–64.

Source: EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata

The data do show that college graduates have fared slightly better than high school graduates since 2007. This is not because of spectacular gains in the wages of college graduates, but because college-graduate wages fell more slowly than the wages of high school graduates. Notably, despite wage declines in both 2013 and 2014, those with advanced degrees are the only ones who have returned to their 2007 real wage levels.

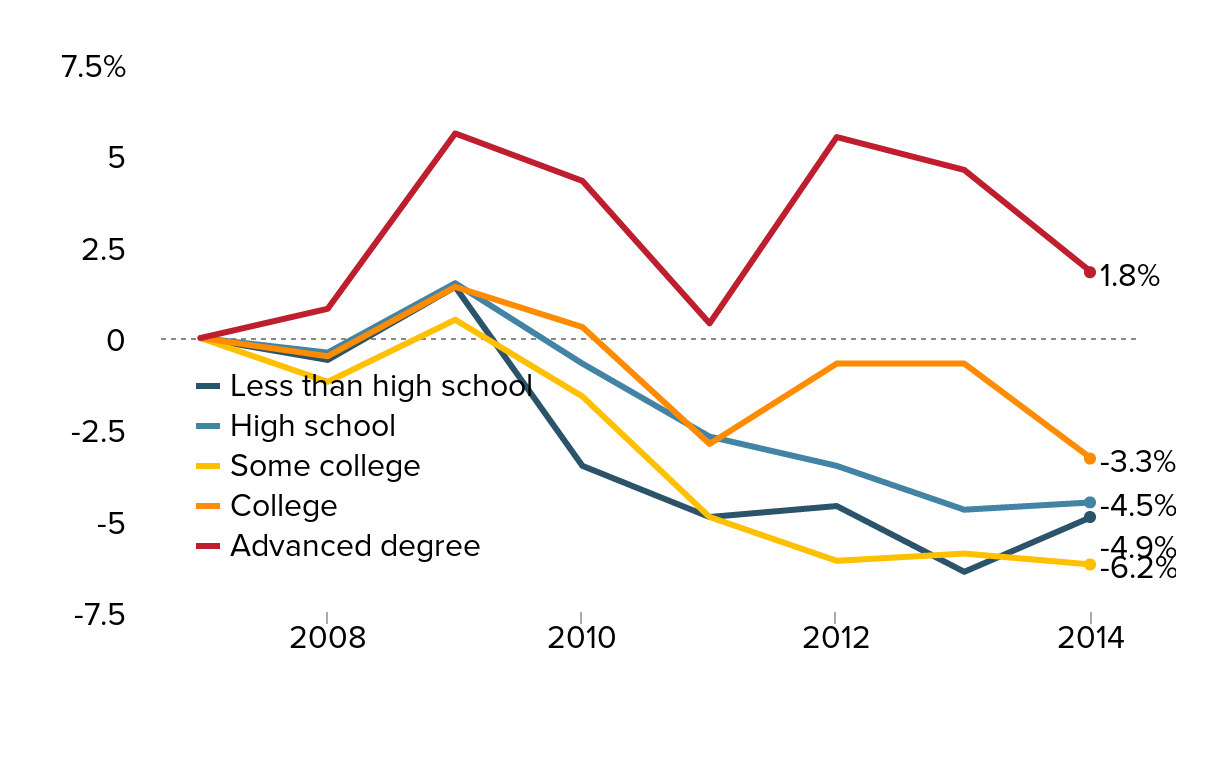

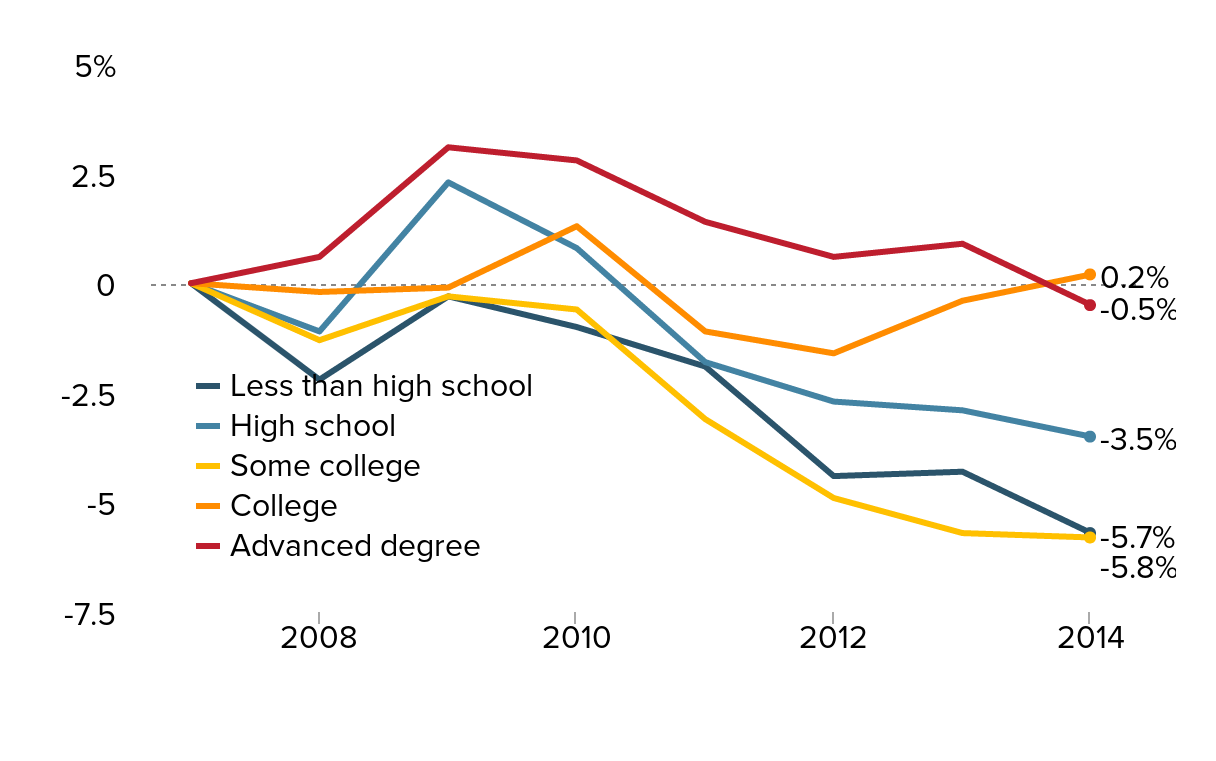

As with wage deciles, a closer examination of how trends in wages by education differ for men and women is also illuminating. Figure F provides cumulative wage trends for men over 2007–2014, while Figure G provides these wage trends for women. For both men and women, those with “some college” experienced the largest losses between 2007 and 2014, while only men with an advanced degree experienced significant gains.

Cumulative percent change in real average hourly wages of men, by education, 2007–2014

| Year | Less than high school | High school | Some college | College | Advanced degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 2008 | -0.6% | -0.4% | -1.2% | -0.5% | 0.8% |

| 2009 | 1.4% | 1.5% | 0.5% | 1.4% | 5.6% |

| 2010 | -3.5% | -0.7% | -1.6% | 0.3% | 4.3% |

| 2011 | -4.9% | -2.7% | -4.9% | -2.9% | 0.4% |

| 2012 | -4.6% | -3.5% | -6.1% | -0.7% | 5.5% |

| 2013 | -6.4% | -4.7% | -5.9% | -0.7% | 4.6% |

| 2014 | -4.9% | -4.5% | -6.2% | -3.3% | 1.8% |

Note: Sample based on all workers age 18–64.

Source: EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata

Cumulative percent change in real average hourly wages of women, by education, 2007–2014

| Year | Less than high school | High school | Some college | College | Advanced degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 2008 | -2.2% | -1.1% | -1.3% | -0.2% | 0.6% |

| 2009 | -0.3% | 2.3% | -0.3% | -0.1% | 3.1% |

| 2010 | -1.0% | 0.8% | -0.6% | 1.3% | 2.8% |

| 2011 | -1.9% | -1.8% | -3.1% | -1.1% | 1.4% |

| 2012 | -4.4% | -2.7% | -4.9% | -1.6% | 0.6% |

| 2013 | -4.3% | -2.9% | -5.7% | -0.4% | 0.9% |

| 2014 | -5.7% | -3.5% | -5.8% | 0.2% | -0.5% |

Note: Sample based on all workers age 18–64.

Source: EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata

On the whole, the broad wage trends by education level over the last several years make clear that wage inequality cannot be readily explained by stories about educational credentials and technology. Wage inequality has increased steadily, yet even those with a college diploma or advanced degree have experienced lackluster wage growth far behind the growth of productivity.

Nominal wage growth consistently below target

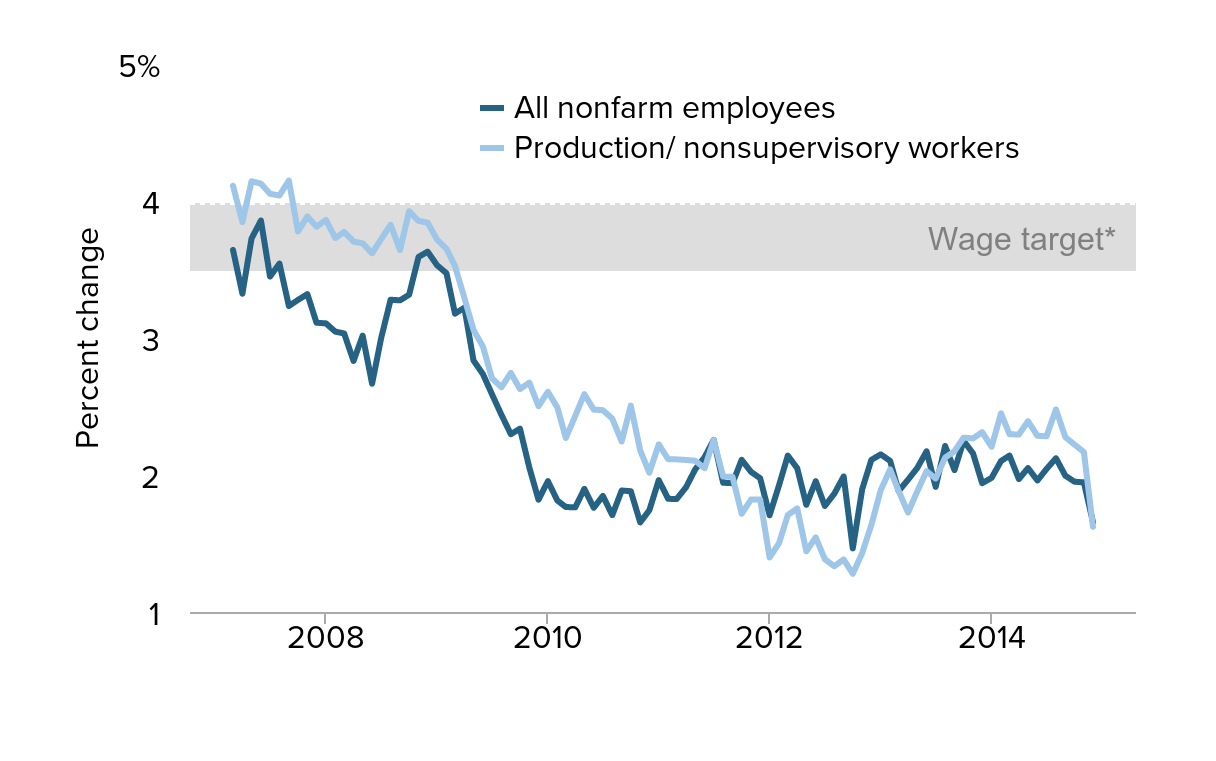

This broad-based lackluster wage growth is not just bad for the living standards of low- and moderate-income households, it’s also a keenly relevant data point in the most important economic policy debate currently being waged: when the Federal Reserve should begin raising short-term interest rates to forestall inflationary pressures, thereby slowing the economy. The clearest rationale for Fed tightening (raising interest rates) is to create slack in the labor market to moderate growth in nominal wages (i.e., wages unadjusted for inflation), which in turn moderates upward pressure on overall prices.

But as we noted before, real wages continued to stagnate if not fall in 2014, even in the face of a deceleration of overall price inflation. Therefore, there is no evidence of upward pressure on nominal wages that should signal that the Federal Reserve should worry about incipient inflation and raise interest rates in an effort to slow the economy.

Figure H shows nominal average hourly earnings for all private-sector workers and for private-sector production/nonsupervisory workers since 2007. It’s clear that nominal wage growth (using either measure) has been flat for a long time—and there’s little evidence this trend has changed in recent months. The horizontal shaded area represents growth of 3.5 to 4 percent—nominal wage growth consistent with the Fed’s 2 percent inflation target plus a range of 1.5–2 percent trend productivity growth and a stable labor share of income. The intuition behind this 3.5–4 percent nominal wage target is simple. If productivity growth (output produced per hour of work) rises by 2 percent, then wage growth of 2 percent is consistent with zero inflation. Yes, labor costs per hour of work are 2 percent higher, but 2 percent more output is being produced, so total costs per unit of output have not risen at all. Given 2 percent productivity growth, only wage growth in excess of 2 percent is consistent with overall price inflation. If nominal wages rise by 4 percent in the face of 2 percent trend productivity growth, this is consistent with stable 2 percent price inflation (the Fed’s stated target). So given trend productivity growth of 1.5–2 percent, we need to see consistent wage growth of 3.5–4 percent before there is any danger that nominal wage growth will put upward pressure on prices sufficient to push them above the Fed’s long-run target.

Year-over-year change in private-sector nominal average hourly earnings, 2007–2014

| All nonfarm employees | Production/nonsupervisory workers | |

|---|---|---|

| Mar-2007 | 3.6427146% | 4.1112455% |

| Apr-2007 | 3.3234127% | 3.8461538% |

| May-2007 | 3.7257824% | 4.1441441% |

| Jun-2007 | 3.8575668% | 4.1267943% |

| Jul-2007 | 3.4482759% | 4.0524434% |

| Aug-2007 | 3.5433071% | 4.0404040% |

| Sep-2007 | 3.2337090% | 4.1493776% |

| Oct-2007 | 3.2778865% | 3.7780401% |

| Nov-2007 | 3.3203125% | 3.8869258% |

| Dec-2007 | 3.1113272% | 3.8123167% |

| Jan-2008 | 3.1067961% | 3.8619075% |

| Feb-2008 | 3.0464217% | 3.7296037% |

| Mar-2008 | 3.0332210% | 3.7746806% |

| Apr-2008 | 2.8324532% | 3.7037037% |

| May-2008 | 3.0172414% | 3.6908881% |

| Jun-2008 | 2.6666667% | 3.6186100% |

| Jul-2008 | 3.0000000% | 3.7227950% |

| Aug-2008 | 3.2794677% | 3.8263849% |

| Sep-2008 | 3.2747983% | 3.6425726% |

| Oct-2008 | 3.3159640% | 3.9249147% |

| Nov-2008 | 3.5916824% | 3.8548753% |

| Dec-2008 | 3.6303630% | 3.8418079% |

| Jan-2009 | 3.5310734% | 3.7183099% |

| Feb-2009 | 3.4725481% | 3.6516854% |

| Mar-2009 | 3.1775701% | 3.5254617% |

| Apr-2009 | 3.2212885% | 3.2924107% |

| May-2009 | 2.8358903% | 3.0589544% |

| Jun-2009 | 2.7365492% | 2.9379157% |

| Jul-2009 | 2.5889968% | 2.7056875% |

| Aug-2009 | 2.4390244% | 2.6402640% |

| Sep-2009 | 2.2977941% | 2.7457441% |

| Oct-2009 | 2.3383769% | 2.6272578% |

| Nov-2009 | 2.0529197% | 2.6746725% |

| Dec-2009 | 1.8198362% | 2.5027203% |

| Jan-2010 | 1.9554343% | 2.6072787% |

| Feb-2010 | 1.8140590% | 2.4932249% |

| Mar-2010 | 1.7663043% | 2.2702703% |

| Apr-2010 | 1.7639077% | 2.4311183% |

| May-2010 | 1.8987342% | 2.5903940% |

| Jun-2010 | 1.7607223% | 2.4771136% |

| Jul-2010 | 1.8476791% | 2.4731183% |

| Aug-2010 | 1.7070979% | 2.4115756% |

| Sep-2010 | 1.8867925% | 2.2447889% |

| Oct-2010 | 1.8817204% | 2.5066667% |

| Nov-2010 | 1.6540009% | 2.1796917% |

| Dec-2010 | 1.7426273% | 2.0169851% |

| Jan-2011 | 1.9625335% | 2.2233986% |

| Feb-2011 | 1.8262806% | 2.1152829% |

| Mar-2011 | 1.8246551% | 2.1141649% |

| Apr-2011 | 1.9111111% | 2.1097046% |

| May-2011 | 2.0408163% | 2.1041557% |

| Jun-2011 | 2.1295475% | 2.0493957% |

| Jul-2011 | 2.2566372% | 2.2560336% |

| Aug-2011 | 1.9434629% | 1.9884877% |

| Sep-2011 | 1.9400353% | 1.9864088% |

| Oct-2011 | 2.1108179% | 1.7169615% |

| Nov-2011 | 2.0228672% | 1.8210198% |

| Dec-2011 | 1.9762846% | 1.8210198% |

| Jan-2012 | 1.7060367% | 1.3982393% |

| Feb-2012 | 1.9247594% | 1.5018125% |

| Mar-2012 | 2.1416084% | 1.7080745% |

| Apr-2012 | 2.0497165% | 1.7561983% |

| May-2012 | 1.7826087% | 1.4425554% |

| Jun-2012 | 1.9548219% | 1.5447992% |

| Jul-2012 | 1.7741238% | 1.3853258% |

| Aug-2012 | 1.8630849% | 1.3340174% |

| Sep-2012 | 1.9896194% | 1.3839057% |

| Oct-2012 | 1.4642550% | 1.2787724% |

| Nov-2012 | 1.8965517% | 1.4307614% |

| Dec-2012 | 2.1102498% | 1.6351559% |

| Jan-2013 | 2.1505376% | 1.8896834% |

| Feb-2013 | 2.1030043% | 2.0408163% |

| Mar-2013 | 1.8827557% | 1.8829517% |

| Apr-2013 | 1.9658120% | 1.7258883% |

| May-2013 | 2.0504058% | 1.8791265% |

| Jun-2013 | 2.1729868% | 2.0283976% |

| Jul-2013 | 1.9132653% | 1.9736842% |

| Aug-2013 | 2.2118248% | 2.1265823% |

| Sep-2013 | 2.0356234% | 2.1739130% |

| Oct-2013 | 2.2495756% | 2.2727273% |

| Nov-2013 | 2.1573604% | 2.2670025% |

| Dec-2013 | 1.9401097% | 2.3127200% |

| Jan-2014 | 1.9789474% | 2.2055138% |

| Feb-2014 | 2.1017234% | 2.4500000% |

| Mar-2014 | 2.1419572% | 2.2977023% |

| Apr-2014 | 1.9698240% | 2.2954092% |

| May-2014 | 2.0510674% | 2.3928215% |

| Jun-2014 | 1.9599666% | 2.2862823% |

| Jul-2014 | 2.0442219% | 2.2828784% |

| Aug-2014 | 2.1223471% | 2.4789291% |

| Sep-2014 | 1.9950125% | 2.2761009% |

| Oct-2014 | 1.9510170% | 2.2222222% |

| Nov-2014 | 1.9461698% | 2.1674877% |

| Dec-2014 | 1.6549441% | 1.6216216% |

* Nominal wage growth consistent with the Federal Reserve Board's 2 percent inflation target, 1.5 percent productivity growth, and a stable labor share of income

Source: EPI analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Employment Statistics public data series

Table 5 adds further dimension to the nominal wage series shown in Figure H. In addition to the monthly nominal wage series from the Current Establishment Statistics, Table 5 also includes data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Employment Cost Index, the Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group, and the BLS quarterly measure of median usual weekly earnings. Taken together, these data series tell a consistent story about nominal wages. None of them is even approaching strong enough growth to reach the target zone. It is clear that the Fed should not even consider raising interest rates to forestall inflation until wage growth is consistently stronger.

Percent change in nominal wages or total compensation, 2013–2014

| Private | |

|---|---|

| CES, monthly | |

| All workers | 1.7% |

| Production/nonsupervisory | 1.6% |

| ECI, quarterly | |

| Total compensation | 2.3% |

| Wages and salaries | 2.2% |

| Civilian | |

| CPS ORG, semiannual | |

| Median | 1.7% |

| Average | 1.7% |

| BLS, quarterly | |

| Median usual weekly earnings, full-time wage and salary workers | 1.7% |

Note: Changes were calculated from the latter end of each year (i.e., monthly data were calculated from December 2013 to December 2014; quarterly data were calculated from 2013Q4 to 2014Q4; semiannual data were calculated from second half 2013 to second half 2014).

Source: EPI analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Current Establishment Statistics (CES) public data series, BLS Employment Cost Index (ECI), Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group (CPS ORG) microdata, BLS Current Population Survey public data series

Finally, it’s crucial to note that genuinely restoring labor market health likely requires a period of wage growth even higher than this 3.5–4 percent target. Consistent wage growth of well over 4 percent would result in a desirable boost in labor’s share of national income—the share of total income received by workers in the form of wages and benefits. Labor’s share fell dramatically in the early stages of recovery from the Great Recession and has essentially not recouped any of this lost ground. Typically, the labor share rises during recessions because profits fall much faster than wages during downturns. Then, in the early stages of recovery, the labor share falls significantly as profits increase much more rapidly than wages. Usually, the labor share then rises again late in the expansion as labor markets tighten and workers regain the bargaining power necessary to secure wage increases. As of yet, however, there is little evidence that the labor share has begun any reliable rise following its long fall in the recovery from the Great Recession. It is clear that the persistent slack in the labor market is leaving workers with little to no ability to bargain for better wages.

Conclusion

The stagnation of hourly wages is the most important economic issue facing most American families, and most of our key economic challenges hinge on whether or not hourly wages for the vast majority grow. Further, the policy roots of hourly wage trends are deep, but too often downplayed or even ignored. This is particularly true when it comes to labor market policies and business practices; reversing the deteriorating state of labor market standards and protections for low- and moderate-wage workers would be an ideal place to start rebuilding their ability to share in overall economic gains. Recent momentum to raise the federal minimum wage and raise the threshold below which all salaried workers are eligible for overtime pay is a very encouraging beginning. It is also important to protect and strengthen workers’ rights to bargain collectively for higher wages and better benefits; regularize undocumented workers, which would lift their wages and the wages of those in the same fields of work; and ensure workers can earn paid sick leave and paid family leave, which would provide a greater measure of economic security and allow for a better balance between work and family (Mishel 2015).

Furthermore, the Federal Reserve needs to keep its foot off the brakes and allow the recovery to gain a firmer foothold. This will help to ensure that the economy continues to recover and that the rebounding economy benefits all workers through higher wages. Even better policy would include additional fiscal stimulus, which could spur acceleration in the economic recovery and lead to real increases in wages and improvements in living standards that are widely shared.

— The author thanks EPI research assistant Will Kimball, EPI data programmer Jin Dai, and EPI editor Michael McCarthy for their valuable contributions to this report.

About the author

Elise Gould, senior economist, joined EPI in 2003 and is the institute’s director of health policy research. Her research areas include wages, poverty, economic mobility, and health care. She is a co-author of The State of Working America, 12th Edition. In the past, she has authored a chapter on health in The State of Working America 2008/09; co-authored a book on health insurance coverage in retirement; published in venues such as The Chronicle of Higher Education, Challenge Magazine, and Tax Notes; and written for academic journals including Health Economics, Health Affairs, Journal of Aging and Social Policy, Risk Management & Insurance Review, Environmental Health Perspectives, and International Journal of Health Services. She holds a master’s in public affairs from the University of Texas at Austin and a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

References

Bivens, Josh, Elise Gould, Lawrence Mishel, and Heidi Shierholz. 2014. Raising America’s Pay: Why It’s Our Central Economic Policy Challenge. Economic Policy Institute, Briefing Paper No. 378.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (U.S. Department of Labor) Current Employment Statistics program. Various years. Employment, Hours and Earnings—National [database].

Bureau of Labor Statistics (U.S. Department of Labor) National Compensation Survey—Employment Costs Trends. Various years. Employer Costs for Employee Compensation [economic news release].

Cooper, David. 2014. “20 States Raise Their Minimum Wages While the Federal Minimum Continues to Erode.” Working Economics (Economic Policy Institute blog), December 18.

Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata. Various years. Survey conducted by the Bureau of the Census for the Bureau of Labor Statistics [machine-readable microdata file]. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau.

Current Population Survey public data series. Various years. Aggregate data from basic monthly CPS microdata are available from the Bureau of Labor Statistics through three primary channels: as Historical ‘A’ Tables released with the BLS Employment Situation Summary, through the Labor Force Statistics Including the National Unemployment Rate database, and through series reports.

Gould, Elise. 2014. Why America’s Workers Need Faster Wage Growth—And What We Can Do About It, Briefing Paper No. 382.

Mishel, Lawrence. 2015. “Policies that Do and Do Not Address the Challenges of Raising Wages and Creating Jobs.” EPI testimony before the U.S. House Committee on Education and the Workforce hearing on “Expanding Opportunity in America’s Schools and Workplaces,” February 4.

Mishel, Lawrence, Josh Bivens, Elise Gould, and Heidi Shierholz. 2012. The State of Working America, 12th Edition. An Economic Policy Institute book. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL). 2014. “2014-2015 Minimum Wage by State,” December 18.