Issue Brief #138

Unbalanced Acts

A comparison of the proposed minimum wage and tax bills

by Jared Bernstein, Robert S. McIntyre, and Lawrence Mishel

The good news is that an increase in the federal minimum wage looks like a real possibility. How good the news is, however, depends on which of the two competing proposals wins out. The differences between the two proposals are not insignificant, especially when considering the billions of dollars in tax cuts in which the GOP leadership has couched its minimum wage proposal. A comparison of the size and phase-in periods of the competing minimum wage proposals in relation to the proposed $123 billion GOP tax cut package finds that:

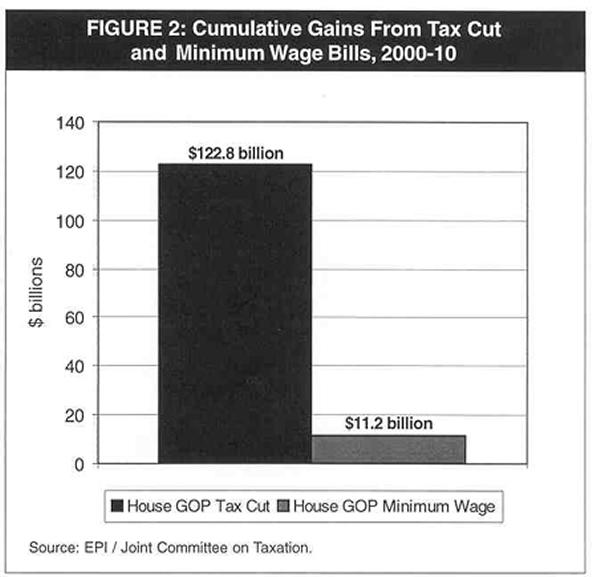

- The $123 billion in tax reductions proposed by the House GOP leadership over the 2000-10 period is nearly 11 times greater than the $11.2 billion in wage hikes that would be generated by its accompanying minimum wage proposal.

- Over the course of a decade, for every dollar in higher wages generated for low-wage workers by the House GOP plan, $10.90 in tax cuts will be provided, mostly for those with the highest incomes.

- While the tax bill’s permanent tax cuts grow to $17.6 billion in fiscal year 2010, the effect of both of the minimum wage proposals will be totally eroded by inflation after fiscal year 2006.

- The Bonior-Kennedy minimum wage proposal’s two-year implementation plan provides a total of $15 billion in higher wages, while the GOP plan’s three-year schedule provides an $11.2 billion gain to these workers, or $3.8 billion less.

- Ninety-one percent of the gains from the GOP’s proposed tax reductions are targeted to the wealthiest 10%, with 73.1% accruing to the richest 1% of households. In contrast, the minimum wage proposals are designed to aid the lowest-income workers.

An analysis of the gains from the tax and minimum wage proposals

Quantifying the aggregate wage gains over the next 10 years under both the Bonior-Kennedy and the House GOP minimum wage proposals (see appendix for methodology) allows for a clear comparison of the proposed minimum wage increases and the proposed tax legislation (Table 1 and Figure 1).

The GOP minimum wage proposal would be phased in over three years, with two annual increases of $0.33 and one of $0.34; the Bonior-Kennedy plan would involve two annual $0.50 increases. After the full implementation of these increases, the effects of the minimum wage hike will decline as inflation continues its ongoing erosion of the value of the minimum wage. After fiscal year 2006, inflation will have eroded the new minimum to the point that it will represent no improvement over the current level. Since it takes the GOP plan an additional year to push the minimum wage to the $6.15 level, the $11.2 billion in cumulative gains under the House GOP plan are significantly less than the $15 billion impact of the Bonior-Kennedy plan.

Ultimately, though, the size of the GOP’s proposed tax cuts quickly dwarfs that of either minimum wage proposal. By fiscal year 2002, the $9.2 billion in proposed tax cuts are nearly three times as large as the cumulative $3.2 billion in minimum wage hikes up to that point. The annual tax cuts eventually rise to $17.6 billion in 2010, but the minimum wage increase’s effect falls to zero after 2006. Thus, the tax cuts grow over time and are permanent, but the minimum wage legislation, while important, has but a temporary impact because neither of the current proposals guarantee further increases after the $6.15 level is reached. (Indexing the minimum wage to inflation or wage growth would remedy this problem of minimum wage erosion.)

The 10-year impact of the House GOP tax legislation – $122.8 billion over the 2000-10 period – is 10.9 times as large as the $11.2 billion in total wage hikes that the GOP’s minimum wage boost would produce (Figure 2). Thus, over the course of 10 years, for every dollar in higher wages generated for low-wage workers by the House GOP plan, $10.90 in tax cuts will be provided for mostly those with the highest incomes in the nation.

The distributional impact of the GOP tax proposal

The distributional assessment of the tax plan (Table 2) is based on the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy Tax Model. Among other things, the GOP tax cuts would:

- Cut the top estate tax rate from 55% to 48%; eliminate the 5% surtax that recaptures the benefits of the lower estate tax rates; reduce other estate tax rates by 2 percentage points; and replace the credit against estate taxes with an exemption (worth more to the largest estates). The $79 billion in estate tax cuts over 10 years are almost two-thirds of the total tax cuts proposed in the bill.

- Increase the write-off for business meals from 50% to 60% of cost under current law.

- Provide added tax breaks for pensions and 401(k) plans.

- Increase the limits on immediate write-offs of business capital investments.

- Speed up the date when 100% of self-employed health insurance can be deducted.

- Restore a loophole for installment sales that was repealed in 1999.

- Expand enterprise zones.

- Provide tax breaks for timber companies.

- Expand the tax credit for investors in low-income housing.

- Augment tax breaks for private tax-exempt bonds.

Table 2 shows that almost all of the benefits of the tax legislation (91.4%) would accrue to the wealthiest 10% of the population. In fact, the wealthiest 1% would get 73.1% of the proposed tax reductions.

A one-dollar increase in the minimum wage provides no economic rationale for tax cuts of the magnitude proposed in the GOP legislation. Yet, as with the last minimum wage increase, Congress again intends to use this opportunity to implement a regressive tax cut. As the above analysis has shown, the benefits to the wealthy from this proposal far outweigh the benefits of the wage increase.

Research assistance from Danielle Gao, Yvon Pho, and Abe Cambier.

The Economic Policy Institute is grateful to The Annie E. Casey Foundation, Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Joyce Foundation, and The Rockefeller Foundation for their support of this work.

APPENDIX: Minimum Wage Simulation Methodology

To determine the aggregate wages generated by a minimum wage increase, one needs to identify the hourly wages and weekly hours of workers in the “affected range,” i.e., those whose wages fall below the proposed new minimum wage. We identify those in the “affected range” by “aging” the 1999 hourly wage distribution found in the Outgoing Rotation Group files of the Current Population Survey by a 2.5% rate of inflation (the long-term rate projected by the Congressional Budget Office). Our analysis assumes that in the absence of a minimum wage increase, low-wage workers would maintain their real wage, seeing no improvement or deterioration. This assumes wage growth depletes the size of the working population in the affected range, as some workers’ wages will eventually exceed that of the newly established minimum wage. (The minimum wage would rise in two annual $0.50 increments in the Bonio

r-Kennedy version and two $0.33 annual increments and a $0.34 increment in the House GOP plan). When those earning $5.15 in 1999 see their earnings reach $6.15, then the minimum wage legislation no longer has any effect, which under our assumptions would take place eight years from now. We assume that the minimum wage increases take effect in April of the relevant year.

The aggregate wage benefit is computed for workers in the affected range as the difference between their simulated wage level and the new minimum ($6.15 in later years; other values in the transition years) multiplied by their average weekly hours for 52 weeks. We increase the wage gain to reflect a labor force growing by 1% annually.

The wage gains associated with minimum wage increases in this simulation would be smaller (larger) if we assumed either a faster (slower) inflation rate or real wage gains (declines).