No, the stock market isn’t throwing a tantrum because the economy is “overstimulated”

Conventional wisdom is firming up quickly around the story that recent stock price declines are a result of the market realizing (in proper Wile E. Coyote fashion) that the economy has overheated. This conclusion is far too premature and ignores plenty of contrary evidence.

The story goes that the 2.9 percent year-over-year wage growth in last Friday’s jobs report is a signal that a tsunami of inflation is heading our way. This would force the Fed to step in and stop the inflationary wave by sharply hiking interest rates. Higher interest rates, in turn, can depress stock prices both by restraining overall growth and by attracting people towards buying bonds rather than stocks. The fiscal stimulus provided by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) and new higher spending caps is thought to add fuel to an already raging economic fire (side note: the TCJA is expensive in budgetary terms, but is so inefficient as fiscal stimulus that its effect is very easy to overstate).

People have gotten way ahead of the facts on this. Yes, the unemployment rate is low, but it’s certainly been this low or lower for a longer span of time without the economy overheating. In 1999 and 2000, the unemployment rate averaged 4.1 percent for two years (and sat below 4 percent for five months), and core inflation nudged up for sure but never broke 2 percent (and the Fed had not even specified a 2 percent target in those years).

Other quantity-side labor market indicators, like the share of “prime-age” adults (between 25 and 54) with a job, have recovered steadily for years, but are still firmly below pre-Great Recession levels—and have certainly not reached historically low levels.

Friday’s 2.9 percent wage growth is certainly on the high side of what we’ve seen during this recovery, but it’s hardly out-of-sample large: in July 2016 and September 2017 wage growth was 2.8 percent. Further, 2.9 percent nominal wage growth is just not that high—it is actually consistent with wages pulling overall price inflation below the Fed’s 2 percent target, so long as productivity growth is running at over 0.9 percent. In recent years, productivity growth has been below 1 percent, but there are certainly signs that it may be rebounding—which is exactly what you’d expect (and want) if the labor market really was tightening up and nudging up wages. We really need to see more than one month of 2.9 percent wage growth to declare the economy on fire; remember, this wage growth measure the preceding three months averaged just 2.5 percent.

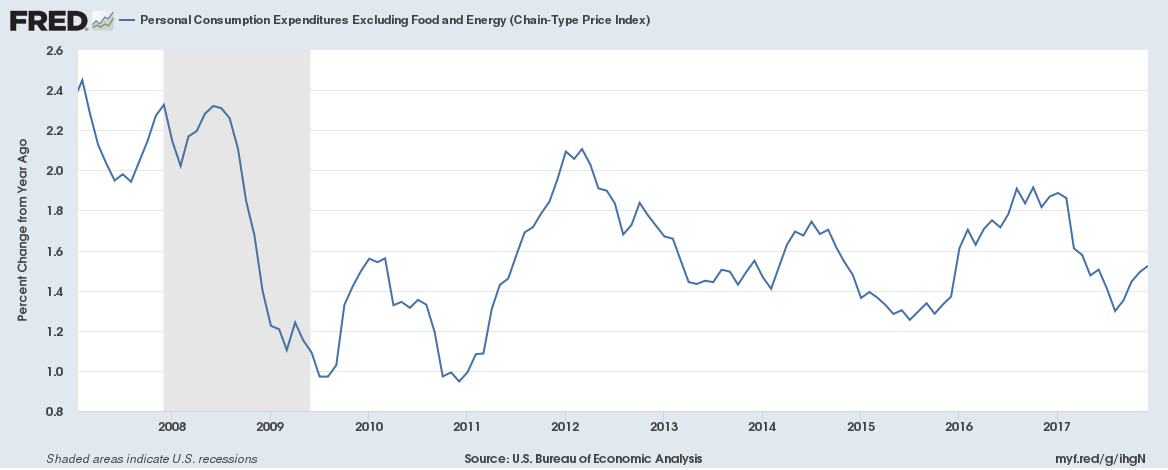

For the Fed, the ultimate measure of whether the economy is overheating is greater than 2 percent inflation in the prices for personal consumption expenditures, excluding volatile food and energy prices. Does this look like an economy overheating to you?

Am I completely positive we’re not at (or at least very, very near) full employment? No, but nobody can be positive that we are, unless they’re determined to ignore lots of data signals. Since there is uncertainty, and because the benefits of tightening labor markets and more people getting jobs are so huge, we need to continue to probe just how low unemployment can go without sparking inflation. What we certainly don’t need to do is let a stock market freakout convince us that no further progress can be made on this front. This is really important. There will be long lasting damage if we prematurely declare the economy overheated and enact policy measures to rein it in. Millions of workers will be needlessly locked out of work. Tens of millions will get smaller raises.

Finally, it’s important to note that it’s not just OK if we begin exceeding the Fed’s inflation target for an extended period of time, it’s an absolutely necessary part of recovery. We’ve been below the target for most of the past eight years. If we let the Fed pull back on the economy and hold inflation at no higher than 2 percent, this means the Fed will have turned the target into a hard ceiling, not a long-run average. For years the Fed has maintained that their target is an average, not a ceiling. This means that periods of sub-2 percent inflation should be matched by periods where inflation exceeded 2 percent. To change this policy approach to one that says no inflation rate of over 2 percent will ever be allowed would make us less able to deal with the next recession effectively.

To see why it would be damaging to convince people that the Fed will never allow inflation to exceed their 2 percent target, remember that when the Fed cuts interest rates, it is trying to lower the inflation-adjusted cost of borrowing. This “real” interest rate is what people and businesses make decisions based on. This real rate is just the nominal rate that the Fed sets minus the expected rate of inflation. Say that your bank offers you a 2 percent interest rate on a mortgage in an economy where prices (including your salary) are expected to rise 2 percent each year. In this case, you’d be effectively paying zero interest in inflation-adjusted terms, as the money you pay the bank each succeeding year is worth less by exactly the amount of interest you must pay. Now inflation falls to 1 percent, but your mortgage interest rate remains at 2 percent. In this case, your mortgage payment just got more onerous in inflation-adjusted terms.

Say that the Fed allows the inflation to drift up to 2 percent and then holds it firmly there in coming years. In this case, the average inflation rate over the past decade will turn out to be well less than 2 percent, and this could well ratchet our expectation of inflation downwards. This lower expected inflation means that then any given nominal rate that the Fed sets is associated with a higher real interest rate. This is a real problem given that we have run into zero interest rates often in the past, even as the economy continues to suffer. A higher rate of expected inflation gives the Fed more room to cut real rates even when nominal rates hit zero.

So, no, it’s not obvious that the economy is overstimulated, and it would be unwise and damaging to act like it is, as it would leave people out of work and with less leverage to gain raises as well as hamstring the Fed’s ability to fight the next recession.

Enjoyed this post?

Sign up for EPI's newsletter so you never miss our research and insights on ways to make the economy work better for everyone.