Working spouses cause inequality? Can this emerging zombie lie be killed?

A major new zombie lie is being launched: The claim that high inequality is due to more working spouses in high-income households and well-off people increasingly marrying other well-off people. This was part of James Q. Wilson’s recent op-ed in the Washington Post, which I addressed in an earlier blog post (though not on this point). My zombie lie detector went wild, however, after reading a very good New York Times article detailing new research showing “the [education] achievement gap between rich and poor children is widening, a development that threatens to dilute education’s leveling effects.” At the end of the article are two statements by conservative public intellectuals, one from Douglas Besharov and one from Charles Murray, attributing income inequality to working spouses.

To recall, here’s what Wilson wrote: “Affluent people, compared with poor ones, tend to have greater education and spouses who work full time.” Wilson then suggests that if these are the drivers of inequality, then it is best not to do anything about the problem, since, in his words, “We could reduce income inequality by trying to curtail the financial returns of education and the number of women in the workforce—but who would want to do that?”

Here’s what the Times‘ Sabrina Tavernise attributed to Murray in her piece:

The growing gap between the better educated and the less educated, he [Murray] argued, has formed a kind of cultural divide that has its roots in natural social forces, like the tendency of educated people to marry other educated people, as well as in the social policies of the 1960s, like welfare and other government programs, which he [Murray] contended provided incentives for staying single.”

And here’s what Besharov told Tavernise:

There are no easy answers, in part because the problem is so complex… . Blaming the problem on the richest of the rich ignores an equally important driver, he [Besharov] said: two-earner household wealth, which has lifted the upper middle class ever further from less educated Americans, who tend to be single parents. The problem is a puzzle, he [Besharov] said. “No one has the slightest idea what will work. The cupboard is bare.”

The basic claim, it seems, is that well-off families are more likely to have working spouses and that the spouses in well-off families are both more likely to have high earnings. Presumably this phenomenon has been growing, or else it cannot explain growing inequality. I address the issue of the role of the growth of two-earner households and inequality in this post but do not address the issue of assortative mating (rich marrying rich). Also, my focus is whether the “working spouses factor” contributes at all to our understanding of the key dynamic of income inequality, the growing income gap between the top 1 percent and the middle class.

To these folks demographic, rather than economic, trends are generating income inequality. Consequently, economic policy has had no role in causing inequality and can not ameliorate inequality either. Of course, this is only the latest effort to reduce inequality to a demographic phenomenon: The State of Working America has addressed other such claims going back to the first edition in 1988.

To explain inequality is to explain first and foremost the tremendous growth of income, wages and wealth that have accrued to the top 1 percent and the top 0.1 percent since 1979. How does the “working spouse” explanation hold up?

The first thing to note is that the presence of a working spouse, even a highly paid one, can potentially impact household income inequality but says nothing about the tremendous divergence of individual wages over the last few decades. Household incomes aggregate the labor income of all household members (which depends on how many members work, how much they work and how much they are paid), non-labor income (capital gains and so on) and any pensions, government transfers and other income. As we know, the top 1 percent of households managed to more than double its share of national income between 1979 and 2007. Josh Bivens and I have argued that the dynamics underlying growing household income inequality are rising wage inequality, rising inequality in receipt of capital income (capital gains, dividends and so on) and the shift toward more capital income and less wage income. The demographic factor of working spouses is about how people combine into households and does not address and certainly cannot explain the huge increase in the wage growth of the top 1 percent of wage earners versus every other group. Here is the chart on wage growth showing the top 1 percent gaining 131 percent between 1979 and 2010 while those in the bottom 90 percent saw their annual wages rise by 15 percent (mostly in the late 1990s).

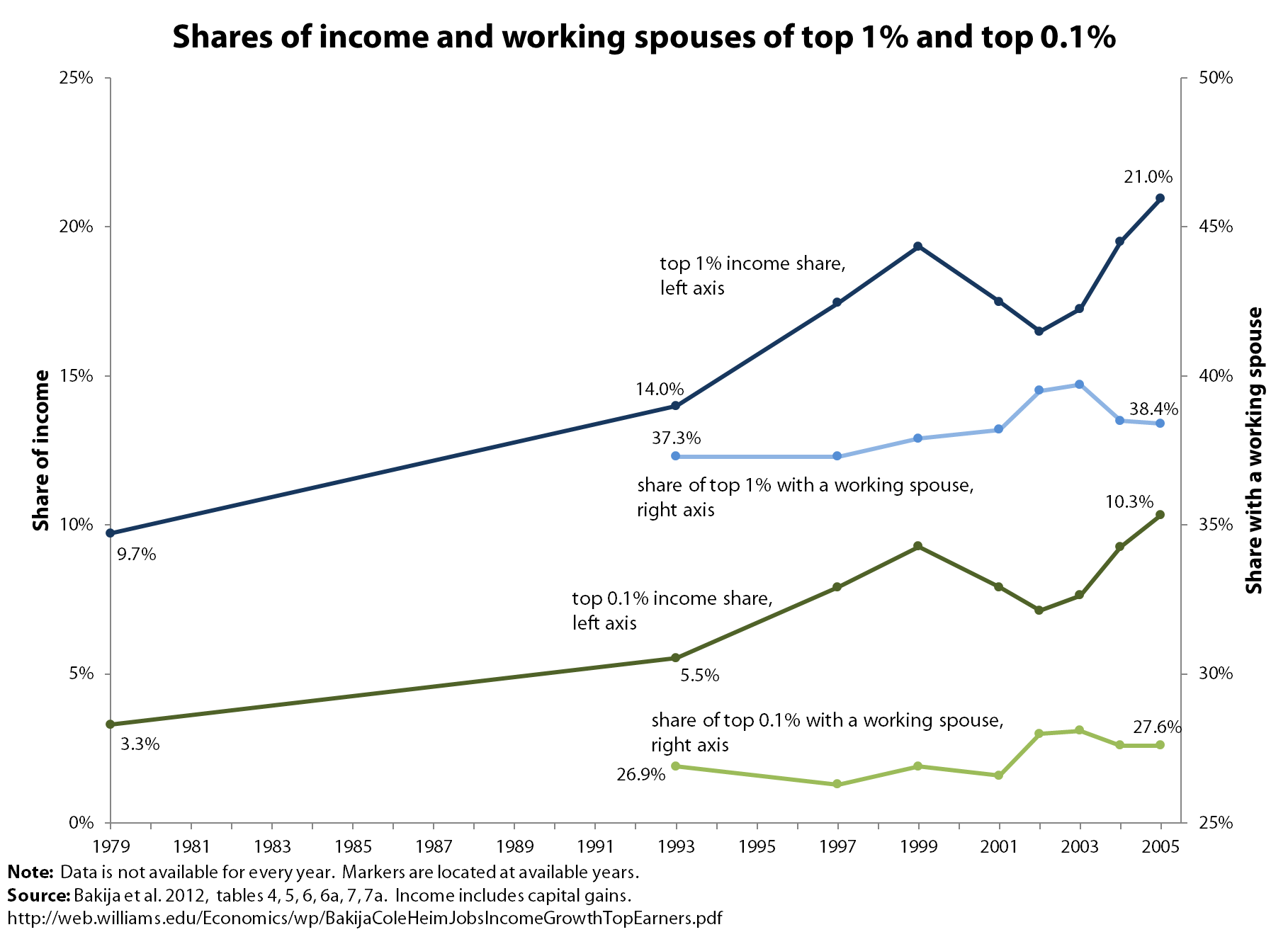

Second, we can look directly at the two–earner phenomenon among the upper 1 percent and the top 0.1 percent from the work of Jon Bakija, Adam Cole and Bradley T. Heim who analyzed tax returns from 1979 to 2005. Unfortunately, they only have complete data on the employment status of spouses starting in 1993 (the only pre-1993 data they present is for 1979 and in at least 30 percent of the households they cannot identify the employment status of spouses). The data are displayed in the graph below. Between 1993 and 2005, the share of national income accruing to the top 1 percent grew from 12.7 percent to 17.0 percent excluding capital gains and from 14 percent to 21 percent when capital gains (shown in the graph) are included. What about the trend in working spouses? Well, the share of households in the top 1 percent with a working spouse was 37 percent in 1993 and … drum roll … 38 percent in 2005. No real change.

The same pattern holds for the top 0.1 percent as well. Their income share grew substantially between 1993 and 2005, up from 4.6 percent to 7.3 percent excluding capitals gains and up from 5.5 percent to 10.3 percent when including capital gains. While income shares of the top 0.1 percent grew tremendously, the share of households with a working spouse grew from 26.9 percent to just 27.6 percent from 1993 to 2005.

Bakija, Cole and Heim do have information on the occupations of the working spouses and the occupational distribution in 1993 does not seem all that different than in 2005. Just focusing on what is probably the two lowest-paid occupational categories—blue collar/misc. services and government/teaching/social services—the share of spouses in those occupations fell from about 35 percent in 1993 to roughly 30 percent in 2005. That trend (a slight shift among the less than 40 percent of top 1 percent households with a working spouse) does not seem to me to be one that generated much of an increase in inequality.

Third, income inequality between the top and the middle could grow if the top 1 percent maintained a similar share of households with working spouses (as we saw above), but the middle class experienced a decline in working spouses. I don’t think the broad middle class, however, has cut back on its work hours or its reliance on two-earners. Census data (Table F-7. Type of Family (All Races) by Median and Mean Income) show the share of families (across all income categories) with a working spouse was pretty much the same in 1993 (47 percent) as in 2005 (45.8 percent). When I analyzed data on the amount of female earnings in the middle three-fifths and the top fifth over time (1979 to 2006), it appears that women’s earnings contributed more to family income comparably in the middle and the top (see Table 2). I could not find data on the share of middle-class households with working spouses, but I suspect that has not changed much or actually increased since 1993. Gary Burtless has found that a “higher correlation of husband and wife earnings” explained a small part (13 percent) of the overall growth of inequality from 1979 to 1996; nevertheless, this finding does not inform us about the drivers of the income gap between the top 1 percent and the middle class (Gary affirms this point via correspondence).

We have generated other useful evidence, like data on the total family work hours of married couple families (with children) by income fifth for The State of Working America. Unfortunately, our data do not break out the top 5 percent and definitely does not identify the top 1 percent (samples being too small for that in the March Current Population Survey). However, the data do show that husbands and wives in the top fifth work roughly 10 percent more total hours than those in the middle fifth or the broad middle (the middle 60 percent). However, the gap in total family work hours between the top fifth and the middle (defined as the middle fifth or 60 percent) has narrowed slightly over 1989 to 2007, a trend that does not exacerbate income inequalities.

So, I do not see any evidence that the pattern of working spouses or “rich marrying rich” explains the growing income gap between the top 1 percent and the middle class. I imagine, though, that we will hear the claim that working spouses explain income inequality much more in the future.

Enjoyed this post?

Sign up for EPI's newsletter so you never miss our research and insights on ways to make the economy work better for everyone.