Summary

The Congressional Progressive Caucus (CPC) has unveiled its fiscal year 2017 (FY2017) budget, titled “The People’s Budget—Prosperity not Austerity.” It builds on recent CPC budget alternatives in setting the following priorities: near-term job creation, financing public investments, strengthening low- and middle-income families’ economic security, raising adequate revenue to meet budgetary needs while restoring fairness to the tax code, strengthening social insurance programs, and ensuring long-run fiscal sustainability.

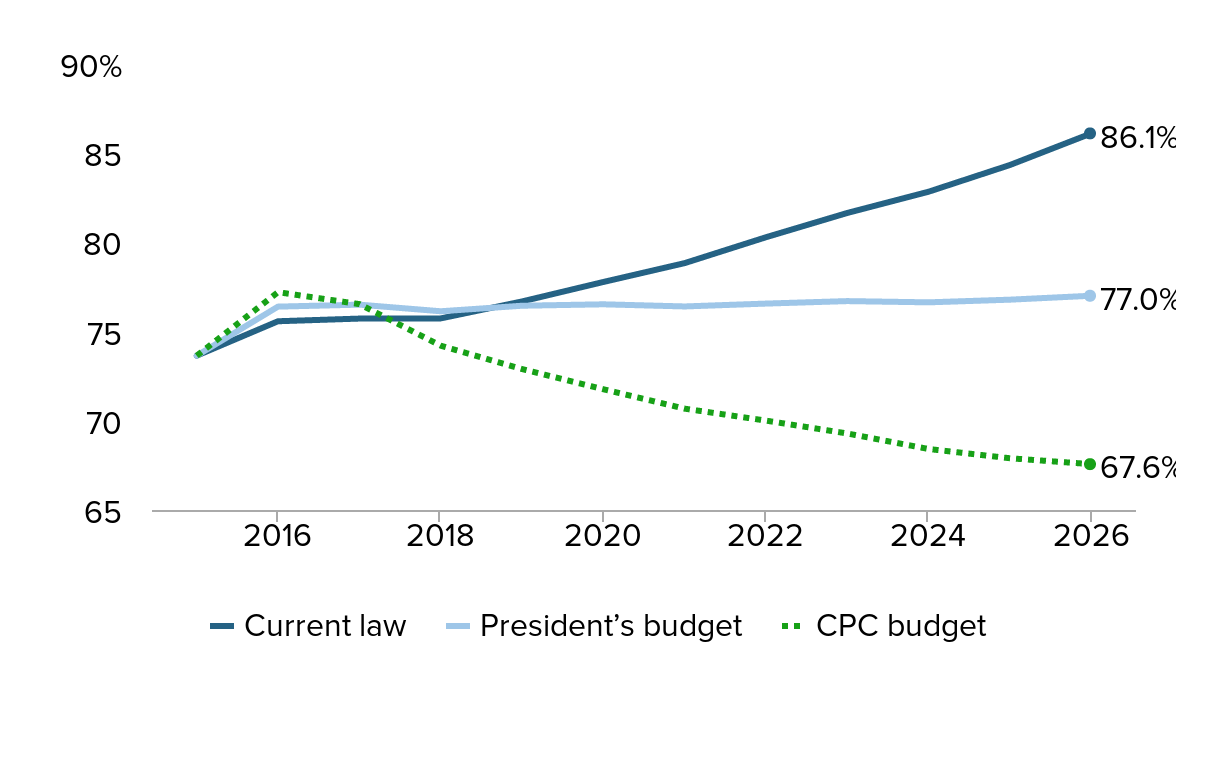

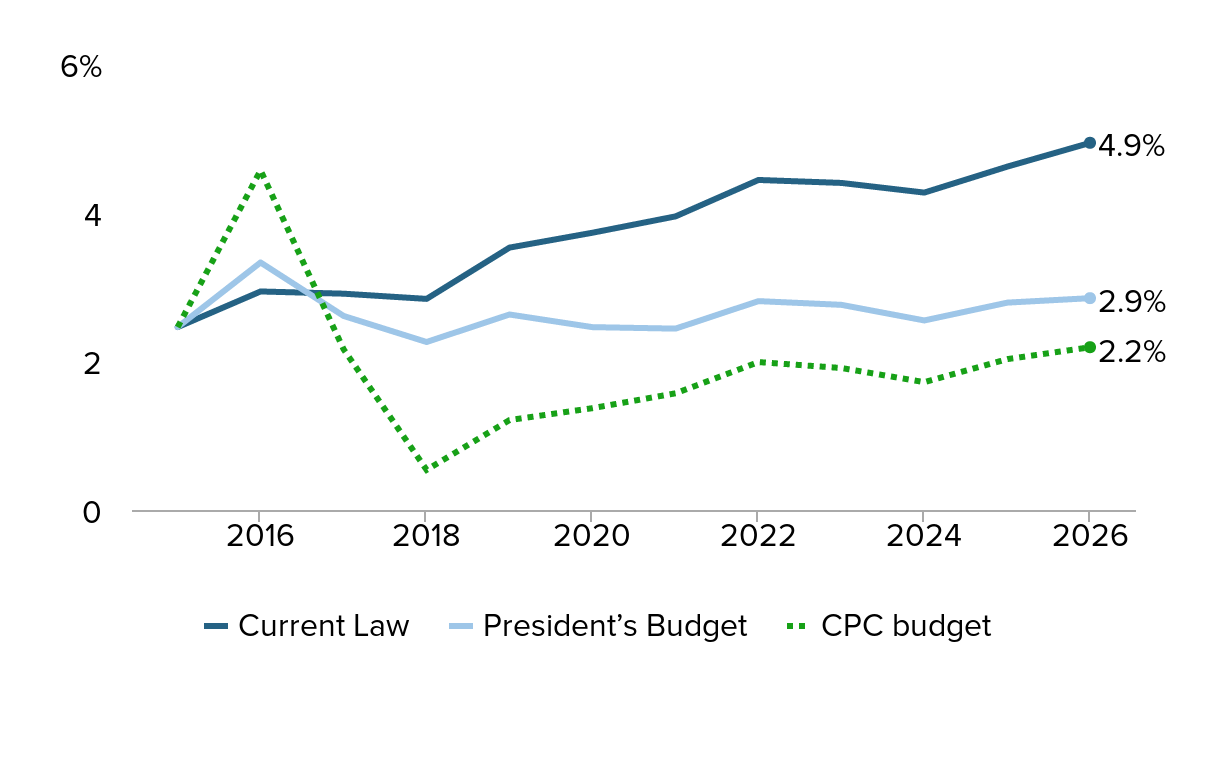

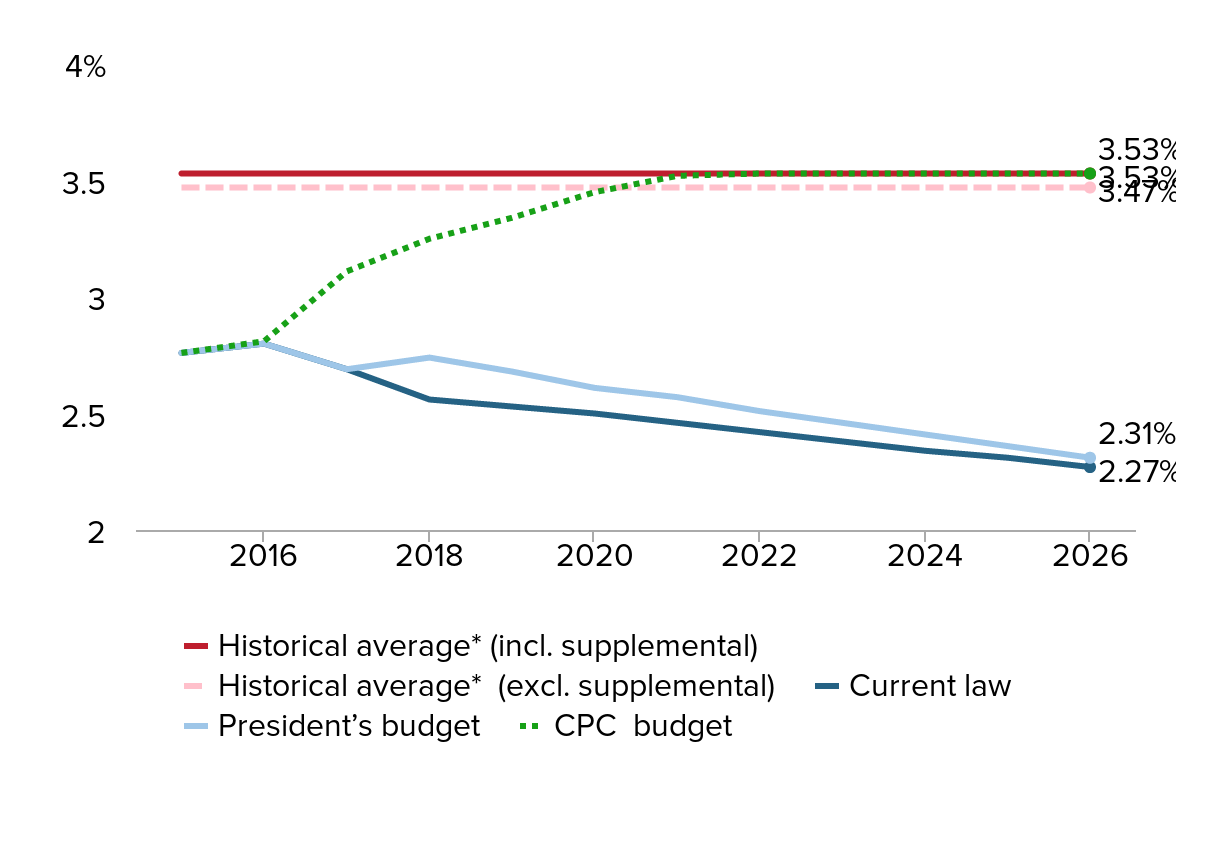

Figures A–C, visualizing The People’s Budget’s impacts on deficits, debt, and nondefense discretionary funding compared with current law, the president’s budget, and historical averages, appear in the body of the report. Tables 1 and 2 detailing the policy changes within the budget; and summary tables 1 through 4 depicting budget totals as well as comparisons with the current law baseline, appear at the end of the report.

The People’s Budget aims to improve the economic well-being of low- and middle-income families by finally closing the persistent jobs gap that has plagued the U.S. economy since the Great Recession began. For that purpose, The People’s Budget provides upfront economic stimulus large enough to go beyond closing the CBO’s measure of the output gap (a measure of how far from potential the economy is operating). The budget would close the output gap and target genuine full employment by pushing the unemployment rate down to 4 percent.

This paper details the budget baseline assumptions, policy changes, and budgetary modeling used in developing and scoring The People’s Budget, and it analyzes the budget’s cumulative fiscal and economic impacts, notably its near-term impacts on economic recovery and employment.1

We find that The People’s Budget would have significant, positive impacts. Specifically, it would:

- Finally complete the economic recovery. The People’s Budget would sharply accelerate economic and employment growth; it would boost gross domestic product (GDP) by 3 percent and employment by 3.6 million jobs in the near term. This would both close the CBO estimate of the output gap and further push unemployment down, to 4 percent, our estimate of genuine full employment. The budget would also ensure that the mixture of spending and revenue changes provides a net fiscal boost long enough to avoid a future fiscal cliff (i.e., a sharp drop in demand caused by budget deficits closing too quickly to sustain growth) that could throw recovery into reverse.2

- Make necessary public investments. The budget finances roughly $295 billion in job-creation and public-investment measures in calendar year 2016 alone and roughly $565 billion over calendar years 2016–2017.3 This fiscal expansion is consistent with the amount of fiscal support needed to rapidly reduce labor market slack and restore the economy to full health. Furthermore, The People’s Budget also aims to hit more ambitious long-term public investment targets, by returning nondefense discretionary spending (NDD) to its historical average as a percentage of GDP by 2021.

- Facilitate economic opportunity for all. By expanding tax credits and other programs for low- and middle-wage workers, boosting public employment, and offering incentives for employers to create new jobs, The People’s Budget aims to boost economic opportunity for all segments of the population.

- Strengthen the social safety net. The People’s Budget strengthens the social safety net and proposes no benefit reductions to social insurance programs—in other words, it does not rely on simple cost-shifting to reduce the budgetary strain of health and retirement programs. Instead, it uses government purchasing power to lower health care costs (health care costs are the largest threat to long-term fiscal sustainability) and builds upon efficiency savings from the Affordable Care Act. The budget also expands and extends emergency unemployment benefits and increases funding for education, training, employment, and social services as well as income security programs in the discretionary budget.4

- Smartly cut spending. The budget focuses on modern security needs by repealing sequestration cuts and spending caps that affect the Defense Department but replacing them with similarly sized funding reductions that are less front-loaded and will allow more considered cuts. It ends emergency overseas contingency operation (OCO) spending in FY2017 and beyond, and ensures a slow rate of spending growth for the Defense Department for the remainder of the decade.

- Increase tax progressivity and adequacy. The budget restores adequate revenue and pushes back against income inequality by adding higher marginal tax rates for millionaires and billionaires, equalizing the tax treatment of capital income and labor income, restoring a more progressive estate tax, eliminating inefficient corporate tax loopholes, levying a tax on systemically important financial institutions, and enacting a financial transactions tax, among other tax policies.

- Reduce the deficit in the medium term. The budget increases near-term deficits to boost job creation, but reduces the deficit in FY2017 and beyond relative to CBO’s current law baseline. The budget would achieve primary budget balance (excluding net interest) and sustainable budget deficits in FY2018 and beyond. After increasing near-term borrowing to restore full employment, the budget gradually reduces the debt ratio in the now full-employment economy over time, actually exceeding a key benchmark of sustainability (of a stable debt-to-GDP ratio during times of full employment). Relative to current law, the budget would reduce public debt by $5.1 trillion (18.5 percent of GDP) by FY2026.

For the sixth year in a row, the Economic Policy Institute Policy Center (EPIPC) has provided assistance to the Congressional Progressive Caucus (CPC) in analyzing and scoring the specific policy proposals in its alternative budget and in modeling its cumulative impact on the federal budget over the next decade. The policies in CPC’s fiscal year 2017 budget—The People’s Budget: Prosperity not Austerity—reflect the decisions of the CPC leadership and staff, not those of EPIPC (although many of the policies included in the budget overlap with policies included in previous EPI budget plans). Upon CPC’s request, the nonpartisan Citizens for Tax Justice (CTJ) independently scored the major individual income-tax reforms proposed in The People’s Budget. All other policy proposals have been independently analyzed and scored by EPIPC based on a variety of other sources, notably data from Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT), the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), and the Tax Policy Center (TPC).

Hunter Blair, the author of this year’s analysis, would like to acknowledge former EPI Policy Center staff members Thomas Hungerford, Joshua Smith, Andrew Fieldhouse, and Rebecca Thiess, whose analyses of previous CPC budgets served as the template for this report.

Introduction

The People’s Budget is focused on both short- and long-term economic objectives. In the short run, The People’s Budget targets a rapid and durable return to genuine full employment through the use of expansionary fiscal policy. In the long run, The People’s Budget pushes back on decelerating productivity growth by making necessary and sustained public investments.

The budget was developed from the evidence-based conclusion that the present economic challenge of joblessness results from a continuing shortfall of aggregate demand—the result of the Great Recession and its aftermath—and that the depressed state of economic activity is largely responsible for elevated budget deficits and the recent rise in public debt. Further, much recent research indicates that aggregate demand is likely to remain depressed in coming years without a fiscal boost (this hypothesis about chronic ongoing demand shortages is often referred to as “secular stagnation”). Labor market slack resulting from this continuing demand shortfall is in turn exacerbating the decade-long trend of falling working-age household income and the three-decades-long trend of markedly increasing income inequality.

Moreover, since late 2011, contractionary fiscal policy (reduced government spending) has greatly contributed to the continuing slack in the labor market and stagnant earnings for most workers. The slack in the labor market can still be seen through the low labor-force participation rate, high labor-underutilization rate, and the low employment-to-population ratio of prime-age workers (ages 25–54). Expansionary fiscal policy can help ensure a prompt and durable return to a full-employment economy which will in turn spur rising wages.

Accelerating and sustaining economic growth, promoting economic opportunity, and pushing back against the sharp rise in income inequality remain the most pressing economic challenges confronting policymakers. To directly address these issues, The People’s Budget invests heavily in front-loaded job-creation measures aimed not only at putting people back to work, but also at addressing the deficit in physical infrastructure and human capital investments. In stark contrast to the current austerity trajectory for fiscal policy, The People’s Budget substantially increases near-term budget deficits to finance a targeted stimulus program that would include infrastructure investment, aid to state and local governments, targeted tax credits, and public works programs.5 These types of investments would yield enormous returns—particularly by reducing the long-run economic scarring caused by the underuse of productive resources—and raise national income and living standards. The People’s Budget also seeks to accelerate productivity growth through sustained public investment—in part through $1.2 trillion of much needed infrastructure investments and in part through returning NDD spending to historical levels of 3.5 percent of GDP by 2021 and keeping it there.

Beyond improving middle-class living standards, using expansionary fiscal policy to ensure a rapid return to full employment is fiscally responsible. A significant portion of the sticker price of a fiscal stimulus package will be recouped through higher tax collections and lower spending on automatic stabilizers such as unemployment insurance (programs or policies that offset fluctuations in economic activity without direct intervention by policymakers). Higher levels of economic activity will also decrease near-term budget deficits and public debt as a share of GDP. Ensuring a rapid return to full employment hedges against many downside fiscal risks, notably slower-than-projected economic recovery, larger-than-projected cyclical budget deficits, and decreased long-run potential GDP due to economic scarring, long-lasting damage to individuals’ economic situations, and the economy more broadly. The People’s Budget would further promote fiscal responsibility and a sustainable public-debt trajectory by raising revenues progressively, exploiting health care efficiency savings, and maintaining the reduced spending trajectory of the Department of Defense (DOD). This means that worries that increased deficits in The People’s Budget would put upward pressure on interest rates are misplaced. Interest rate pressure is normally thought to stem from anticipated future budget deficits run while the economy is forecast to be at full employment. But in future years when the economy is at full employment, deficits will be smaller under The People’s Budget.

After increasing near-term borrowing to restore full employment, the budget easily meets the key benchmark of sustainability: stabilizing the debt-to-GDP ratio at full employment. In fact, under The People’s Budget, the future debt-to-GDP ratio will decline in years the economy is at full employment. Relative to current law, the budget would reduce public debt by $5.1 trillion (18.5 percent of GDP).

The economic context for The People’s Budget

More than eight years have passed since the onset of the Great Recession in December 2007, but the economic context for The People’s Budget remains unequivocally tied to the recession for the following reasons.

Slack remains

Growth in the 6.5 years since the recession’s official end has been too sluggish to restore the economy to prerecession conditions, let alone to genuine full employment. While the unemployment rate as of January 2016 stands at 4.9 percent, it likely overstates the extent of labor market recovery. The share of adults age 25–54 with a job—which fell an unprecedented 5.5 percentage points (from 80.3 percent to 74.8 percent) from its peak to trough due to the Great Recession—is now still just 77.7 percent. Further, nominal wage growth has failed to accelerate over the recovery.

The pace of economic growth since the economy emerged from recession in July 2009 has been too sluggish to restore the economy to full health, and this slow pace of growth can be entirely explained by the drag from fiscal policy since 2011. While fiscal policy during and immediately after the recession— particularly the enactment of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA)—was strongly expansionary and arrested the economy’s sharp decline, economic performance has since deteriorated largely because fiscal policy became increasingly contractionary in 2011.

This turn toward fiscal contraction has largely been driven by the enactment of the Budget Control Act (BCA) of 2011, which cut and capped discretionary spending and established the automatic “sequestration” spending cuts that took effect March 1, 2013. Contractionary fiscal measures aside from the BCA—the expiration of the payroll tax cut in January 2013, the expiration of federal emergency unemployment benefits in December 2013, and two rounds of benefit cuts in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance program—have also intensified fiscal drags. The sheer size of the contraction of government spending over the current recovery is unprecedented. If public spending in the current recovery had simply matched the growth trajectory of that of the early 1980s recession and recovery, spending would be at least $800 billion higher now. When multiplier effects are taken into account, this level of spending would have induced a full recovery (Bivens 2014). By prematurely pulling away from fiscal support, policymakers condemned the economy to years of unnecessarily depressed output, anemic growth, high unemployment rates, and large cyclical budget deficits (Bivens, Fieldhouse, and Shierholz 2013). Instead of making recovery the priority, the Washington budget debate remains entirely focused on the one policy intrinsically at odds with spurring near-term economic growth: reducing budget deficits. And deficits will remain high as long as the economy is depressed. It is safe to say that by now the Budget Control Act has been an antistimulus substantially larger than the stimulus provided by the ARRA.

Fiscal expansion can restore genuine full employment

This still-present slack in the labor market means that fiscal expansion could return the economy to genuine full employment. Targeting genuine full employment means more than just closing the CBO’s measure of the output gap. Instead, fiscal expansion should go further and target a 4 percent rate of unemployment. This can only occur if the Federal Reserve does not raise interest rates relative to baseline. In fact, we believe that the Federal Reserve should not raise interest rates until inflation actually appears in the data. For a more in-depth discussion of this view, see the EPI report by Josh Bivens setting the context for this analysis.

Using fiscal policy to boost aggregate demand is not only the key to achieving a durable return to full employment, it will also actually substantially finance itself and improve key metrics of fiscal health (notably the public debt-to-GDP ratio) in the near term, as the extra economic activity it spurs leads to higher tax collections and lower safety-net spending.

Productivity growth has weakened

A worrisome trend that has emerged fairly recently is that productivity growth has decelerated over the course of the recovery. This means that the benefits of aggressive fiscal policy to restore the economy to full employment and hold it there for a while could be large indeed. Ball, DeLong, and Summers (2014) and Bivens (2014) have shown the damage to estimated long-run GDP by the extended period of running the economy below potential. Reversing the damage already done by—and preventing further damage from—the slack in demand is a key reason why further economic stimulus is needed and why policymakers should be aggressive in pursuing an extended period of full employment. Likewise, in both the short and long run, another way to stem the tide of decelerating productivity growth is through sustained public investment.

The following sections describe the spending proposals and then the revenue policies in The People’s Budget (see Table 1 at the end of this report). The budget is modeled and all policies are scored relative to CBO’s January 2016 current law baseline (CBO 2016). Individual policies and net budgetary impacts, including projected debt-to-GDP (Figure A), deficit-to-GDP (Figure B), and NDD budget authority-to-GDP (Figure C) ratios are compared with CBO’s current law baseline, as well as President Obama’s FY2017 budget request.

Projected public debt as a share of GDP, FY2015–FY2026

| Year | Current law | President’s budget | CPC budget |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 73.65% | 73.65% | 73.65% |

| 2016 | 75.58% | 76.40% | 77.21% |

| 2017 | 75.73% | 76.51% | 76.54% |

| 2018 | 75.74% | 76.14% | 74.21% |

| 2019 | 76.69% | 76.45% | 72.90% |

| 2020 | 77.78% | 76.53% | 71.77% |

| 2021 | 78.84% | 76.41% | 70.68% |

| 2022 | 80.29% | 76.57% | 70.01% |

| 2023 | 81.65% | 76.71% | 69.29% |

| 2024 | 82.84% | 76.64% | 68.42% |

| 2025 | 84.34% | 76.79% | 67.90% |

| 2026 | 86.11% | 77.01% | 67.57% |

Note: For the president's budget, this figure uses CBO's projections of GDP. Data for 2015 represent actual spending.

Source: EPI Policy Center analysis of Congressional Budget Office, Citizens for Tax Justice, Joint Committee on Taxation, Office of Management and Budget, and Tax Policy Center data

Projected deficit as a share of GDP, FY2015–FY2026

| Year | Current Law | President’s Budget | CPC budget |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2.46% | 2.46% | 2.46% |

| 2016 | 2.94% | 3.33% | 4.57% |

| 2017 | 2.91% | 2.61% | 2.16% |

| 2018 | 2.84% | 2.26% | 0.54% |

| 2019 | 3.53% | 2.63% | 1.21% |

| 2020 | 3.73% | 2.46% | 1.37% |

| 2021 | 3.95% | 2.44% | 1.57% |

| 2022 | 4.44% | 2.81% | 1.99% |

| 2023 | 4.40% | 2.76% | 1.91% |

| 2024 | 4.27% | 2.55% | 1.72% |

| 2025 | 4.62% | 2.79% | 2.03% |

| 2026 | 4.94% | 2.85% | 2.19% |

Note: For the president's budget, this figure uses CBO's projections of GDP. Data for 2015 represent actual spending.

Source: EPI Policy Center analysis of Congressional Budget Office, Citizens for Tax Justice, Joint Committee on Taxation, Office of Management and Budget, and Tax Policy Center data

Projected nondefense discretionary budget authority as a share of GDP, excluding supplemental spending, FY2015–FY2026

| Year | Historical average* (incl. supplemental) | Historical average* (excl. supplemental) | Current law | President’s budget | CPC budget |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 3.53% | 3.47% | 2.76% | 2.76% | 2.76% |

| 2016 | 3.53% | 3.47% | 2.80% | 2.80% | 2.81% |

| 2017 | 3.53% | 3.47% | 2.69% | 2.69% | 3.11% |

| 2018 | 3.53% | 3.47% | 2.56% | 2.74% | 3.25% |

| 2019 | 3.53% | 3.47% | 2.53% | 2.68% | 3.34% |

| 2020 | 3.53% | 3.47% | 2.50% | 2.61% | 3.45% |

| 2021 | 3.53% | 3.47% | 2.46% | 2.57% | 3.52% |

| 2022 | 3.53% | 3.47% | 2.42% | 2.51% | 3.53% |

| 2023 | 3.53% | 3.47% | 2.38% | 2.46% | 3.53% |

| 2024 | 3.53% | 3.47% | 2.34% | 2.41% | 3.53% |

| 2025 | 3.53% | 3.47% | 2.31% | 2.36% | 3.53% |

| 2026 | 3.53% | 3.47% | 2.27% | 2.31% | 3.53% |

* Historical average reflects the average nondefense discretionary budget authority as a share of GDP between FY1980 and FY2007 (the last year before the onset of the Great Recession).

Note: Supplemental spending includes war, disaster, emergency, and program integrity. For the president's budget, this figure uses CBO's projections of GDP and undoes reclassifications. Data for 2015 represent actual spending. Data for 2016 exclude Changes in Mandatory Programs.

Source: EPI Policy Center analysis of Congressional Budget Office and Office of Management and Budget data

Outlays in The People’s Budget

The People’s Budget makes targeted investments in job creation and infrastructure spending aimed at rapidly restoring full employment, supporting a sustained recovery, and using public investment to accelerate productivity growth, while also making targeted cuts to reflect national priorities and improve efficiency in the budget.

The People’s Budget ramps up overall spending in the near term to support economic recovery and pursue genuine full employment. The People’s Budget therefore heavily invests in stimulus measures over fiscal years 2016 and 2017 when economic support is most needed (see Table 2 at the end of this report).6 Spending then supports the recovery by ensuring that the mix of spending and revenue changes still provide a fiscal boost relative to baseline. In later years, increased spending largely consists of additional infrastructure spending to help meet estimated needs, as well as sustained increases in NDD spending that return NDD spending to historical averages by 2021 and sustain it there, rather than letting it fall to a 60-year low of 2.3 percent in FY2026, as projected under current law (see Figure C).

As shown in Table 2, The People’s Budget finances $1.8 trillion in mandatory job-creation measures and public investments over FY2016–2026 ($1.5 trillion over FY2017–2026). A large share of the spending consists of sustained investments in infrastructure, green manufacturing, and research and development.

Renewed fiscal expansion to restore full employment

Among the spending measures are those that make up the targeted stimulus program phased in over two years. This stimulus program includes a $208 billion investment in infrastructure, spending that reaches $1.2 trillion over FY2016–2026, which approaches the level the American Society of Civil Engineers calls for to close the nation’s investment shortfall while offering a sustained, continuing dedicated source of funding specifically for infrastructure investments (ASCE 2013).

Other pieces of the stimulus package, totaling $175 billion over FY2016–2017, include investing in teachers and K-12 schools ($15 billion); providing block grants to aid states in rehiring first responders, funding safety net programs, and funding Medicaid ($15 billion); and funding public-works jobs programs to boost employment, with particular emphasis on aiding distressed communities ($114 billion). The package of public-works jobs programs would fully finance one year of initiatives proposed by Rep. Jan Schakowsky’s (D-Ill.) in her Emergency Jobs to Restore the American Dream Act of 2011.7 To provide both an economic boost as well as individual assistance to the still elevated number of long-term unemployed workers, The People’s Budget substantially increases the generosity of the unemployment insurance (UI) system. This budgetary provision implies a total investment of $32 billion from FY2016–2017.8

As shown in Table 2, The People’s Budget also funds a number of job-creation tax measures. It introduces the Hard Work Tax Credit, an expanded version of the now-expired Making Work Pay tax credit, for calendar year 2016. The Hard Work Tax Credit will be equal to that of the old Making Work Pay credit.9 The budget also expands the Earned Income Tax Credit to greatly increase the credit’s generosity to childless workers, thus increasing the program’s work incentive for this group. The $67 billion expansion was highlighted in President Obama’s FY17 budget (OMB 2016). Moreover, The People’s Budget finances $48 billion in tax credits for businesses over FY2017–2026, including an enhanced and simplified research and experimentation credit as well as green-manufacturing incentives.

Strengthening the safety net and investing in education

The People’s Budget expands and strengthens other key provisions of the social safety net as well. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits are expanded by reestablishing the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) levels of SNAP benefits and undoing SNAP cuts from the farm bill (adjustments totaling $26 billion in increased spending from FY2016-2026, as shown in Table 1). To ensure that federal civilian and veteran retirees are not experiencing a decline in their purchasing power, The People’s Budget indexes their retirement benefits to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ experimental consumer price index for elderly households, or CPI-E, which more accurately reflects the buying patterns of American senior citizens. The change will result in additional outlays of $108 billion over FY2017–2026 (see Table 1).

Other spending proposals adopted over FY2017–2026 in The People’s Budget include refinancing student loans and making college more affordable ($412 billion) and adopting the president’s proposed Preschool for All ($66 billion) and End Family Homelessness ($11 billion) initiatives.

Returning NDD public investment to historical levels

In addition to these targeted job-creation measures, infrastructure investments, public investments, and tax credits housed under the mandatory spending portion of the budget, The People’s Budget invests heavily in the core nondefense discretionary (NDD) budget. The NDD budget houses a range of critical public investments in areas such as education, energy, basic scientific research, workforce training, and health. The Budget Control Act (BCA) enacted deep cuts to the NDD budget; repealing these cuts under The People’ Budget starting in FY2017 would result in an additional $513 billion over FY2017–2026 in needed NDD investments. The People’s Budget would also repeal the entirety of the discretionary and mandatory BCA spending caps and sequester cuts.10 In total, the CPC budget policy changes translate to a nearly $1.9 trillion increase in NDD outlays over current law).11 Sustaining these investments is critical for building the country’s stock of public and human capital, a key driver of long-run productivity growth (Bivens 2012a). This boost to long-run productivity is vital given the worrisome trend of decelerating productivity growth.

Summarizing investments and job-creation measures

Investments and job-creation measures in the mandatory and NDD budgets total $509 billion over FY2016–2017 (see Table 2), which, when combined with the other spending and revenue provisions within The People’s Budget, is in line with the level of fiscal support needed to fully close the remaining jobs gap. These NDD investments as well as mandatory changes in The People’s Budget bring total job creation and public investments in The People’s Budget to $3.8 trillion above the current law baseline over FY2016–2026 (see Table 2).12 Critically, NDD budget authority would reach the historical average of 3.5 percent of GDP by 2021, as opposed to averages of 2.5 and 2.6 percent respectively under current law and the president’s FY17 budget request. By FY2026, under The People’s Budget, NDD budget authority is projected to remain at the historical average of 3.5 percent compared with 2.3 percent under current law and the president’s budget (see Figure C). This classification of federal spending is especially vital because much of it is needed public investment—purchases the government can make now that will boost employment in the short run but provide lasting benefits, such as infrastructure and education. Under current law, such investment will soon reach its historical low as a share of GDP and continue to decline thereafter (Smith 2014a).

Targeted spending cuts and health efficiency savings

The People’s Budget also proposes adjusting the pace of defense savings and finding other targeted and efficient savings in the budget. Over FY2017–2026, the CBO 2016 current law baseline includes a $243 billion reduction in DOD outlays from the BCA spending caps and sequestration cuts. The People’s Budget repeals these cuts and replaces them with similarly sized cuts that allow for a more gradual and considered approach to spending reductions. The budget provides $74 billion in budget authority for overseas contingency operations (OCO) for FY2016—the same as the baseline and enough to fund full and safe withdrawal from Afghanistan—after which all OCO funding is ended. Responsibly reducing OCO spending would save $744 billion over FY2017–2026 relative to current law (see Table 1).

The People’s Budget achieves savings outside of the Defense Department as well, many of which would build on the efficiency reforms already enacted in the Affordable Care Act. The budget implements the following policies: the addition of a public insurance option to Affordable Care Act health insurance exchanges, negotiation of Medicare Part D pharmaceutical drug prices with pharmaceutical companies (similar to current negotiation of drug prices through Medicaid), reform of pharmaceutical drug development and patent rules, payment and administrative cost improvements, and efforts to reduce fraud and abuse in Medicaid. In total, implementing these policies would decrease budget deficits by an estimated $473 billion over FY2017–2026 (see Table 1), much more than offsetting the $103 billion revenue loss from repealing the excise tax on high-premium health insurance plans. Along with health savings, The People’s Budget would adopt a proposal in the president’s FY2017 budget to cut $18 billion from crop insurance subsidies—a proposal made necessary by the expansion of the subsidy program in the Agriculture Act of 2014.

Revenue in The People’s Budget

The U.S. tax code is failing in a number of dimensions. Tax receipts have been deliberately driven down to levels that cannot support current national priorities (let alone commitments to an aging population in an economy plagued by high rates of excess health care cost growth). Tax policy has increasingly exacerbated income inequality, and complexity within the tax code means that an individual’s or corporation’s tax bill can too easily depend on the abilities of one’s accountant. The People’s Budget would reform the tax code by enacting policies that would restore lost progressivity (so that effective tax rates reliably rise with income), push back against rising income inequality, raise sufficient revenue, and close inefficient or economically harmful loopholes. Although tax increases are contractionary under current conditions, the economic impact of a dollar of government spending (as shown by the fiscal multiplier) is about three times higher than the economic impact of a dollar of revenue in our estimates. Much of the revenue would be raised from upper-income households and businesses (which have relatively low marginal propensities to consume and thus particularly low fiscal multipliers even among tax changes) and used to finance high bang-per-buck job creation measures. Therefore the relatively small fiscal drag from raising revenue would be more than offset by the other budget policies.

The People’s Budget increases revenues as a share of GDP by 3.8 percent over FY2017–2026, from 18.1 percent under current law to 21.9 percent. Though higher relative to GDP than the previous postwar high of 19.9 percent in 2000 (OMB n.d.), this percentage remains small relative to that of other developed economies (even when state and local tax rates are taken into account). Moreover, aside from the United States, the great majority of advanced economies have increased their revenue-to-GDP ratios in recent decades (OECD n.d.), a logical extension of greater national wealth and aging populations.

Individual income tax reforms

The People’s Budget raises individual income tax revenue relative to current law by enacting what was referred to as “Obama policy” prior to enactment of the American Tax Payer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA); that is, it allows Bush-era tax rate reductions to expire for tax filers with adjusted gross income (AGI) above $200,000 ($250,000 for joint filers).13 Though tax rates were scheduled to revert to Clinton-era levels at midnight on December 31, 2012, the ATRA extended the income tax cuts for those with AGI under $400,000 ($450,000 for married couples), making permanent the reduction to the 25, 28, and 33 percent brackets and creating a new 35 percent bracket for taxable income up to a $400,000 threshold.14 Under The People’s Budget the 33 percent bracket would revert to 36 percent and the 35 percent bracket would revert to 39.6 percent. The AGI threshold at which the personal exemption phase-out and limitation on itemized deductions are triggered would be lowered from $300,000 ($350,000 for joint filers) to $200,000 ($250,000 for joint filers).

The People’s Budget would increase progressivity of the individual income tax code by adding the five higher marginal tax rates at higher income thresholds from Rep. Schakowsky’s Fairness in Taxation Act of 2011, effective January 1, 2014: a 45 percent bracket starting at taxable income above $1 million; a 46 percent bracket at taxable income above $10 million; a 47 percent bracket at taxable income above $20 million; a 48 percent bracket at taxable income above $100 million; and a 49 percent bracket at taxable income above $1 billion.15 Across this modified rate structure, the budget would also tax all capital gains and dividends as ordinary income. The collective impact of these policies—raising taxes on households with AGI above $200,000 ($250,000 for joint filers), adding five additional high-income brackets, and equalizing treatment of investment and labor income—would generate almost $1.6 trillion over FY2017–2026 relative to current law.16

As Table 1 shows, The People’s Budget makes a number of additional policy changes to the individual income tax code. The budget repeals the step-up basis for capital gains at death ($825 billion in new revenue over FY2017–2026); increases progressivity in the tax code by capping the value of itemized deductions at 28 percent ($646 billion); denies the home-mortgage interest deduction for yachts and vacation homes ($10 billion); and ends the exclusion of foreign earned income ($83 billion). The budget would ensure all pass-through entities are subject to the self-employment tax and the 3.8 percent ACA Medicare tax ($272 billion in revenue over FY2017–2026). Finally, The People’s Budget would enact comprehensive immigration reform that includes a path to citizenship, resulting in more taxpayers paying income and payroll taxes, and it would qualify these residents for refundable tax credits (on net saving $216 billion over FY2017–2026).

Corporate income-tax loophole closers

On the corporate side, The People’s Budget eliminates some of the most egregious loopholes and enacts other progressive reforms. The budget repeals voluntary deferral of taxes owed on U.S.-controlled foreign companies’ source income, ends the Subpart F active financing exception, reforms treatment of the foreign tax credit, and includes an anti-inversion proposal for savings of $1 trillion over FY2017–2026 (OMB 2015). It curbs corporate deductions for stock options (saving $32 billion), limits the deductibility of bonus pay ($42 billion), eliminates corporate jet provisions ($3 billion), and reduces the level of deductibility of corporate meals and entertainment ($71 billion) over FY2017–2026. It saves $139 billion over FY2017–2026 by eliminating fossil fuel preferences through enactment of the End Polluter Welfare Act (EPWA) sponsored by Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Rep. Keith Ellison (D-Minn.). The budget also ends tax deductions for the direct advertising of certain unhealthy foods to children ($20 billion over FY2017–2026).

Taxes on economic ‘bads’ and other tax reforms

Besides increasing progressivity in the individual and corporate income tax codes, The People’s Budget reflects the belief that government should levy Pigovian taxes so that the consumption of certain goods reflects their true societal costs. The People’s Budget imposes a financial transactions tax (FTT) in order to raise significant revenue while dampening speculative trading and encouraging more productive investment. By adhering to the same tax base and rates as the FTT proposed in the Back to Work budget (the CPC’s budget for FY2014), the FTT in The People’s Budget would raise $924 billion over FY2017–2026 (Fieldhouse and Thiess 2013).17 The budget would also enact an idea proposed by former House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Dave Camp (R-Mich.) by imposing a 0.35 percent tax on “systemically important financial institutions,” assessed quarterly, to address the issue of “too big to fail”($111 billion raised over FY2017–2026) (JCT 2014).

To reduce the emission of greenhouse gases and yield significant revenue on an annual basis, the budget would price carbon emissions starting at $25 per metric ton in 2017 and indexed at a 5.6 annual rate. Because pricing carbon has the potential to be regressive, The People’s Budget, like the Better Off Budget before it, would rebate 25 percent of the revenue from carbon abatement as refundable credits to low- and middle-income households. Net of this rebate, carbon pricing would raise $1.3 trillion in revenue over FY2017–2026. On a much smaller scale, The People’s Budget increases the federal excise tax on cigarettes by $0.50 per pack, raising $35 billion over FY2017–2026. The People’s Budget also includes the president’s $10.25 per barrel fee on oil and dedicates the $319 billion to the Highway Trust Fund.

Finally, the budget restores the progressive taxation of inherited wealth by instituting a progressive estate tax ($231 billion over FY2017–2026). It enacts Sen. Sanders’s Responsible Estate Tax Act of 2010, which sets an exemption level of $3.5 million and a graduated rate that rises to 55 percent for estates valued at over $50 million. The bill would levy a 10 percent surtax on estates valued at over $500 million.

In total, The People’s Budget raises $8.8 trillion in additional revenue relative to current law (see Summary Table 3). Revenue levels in the budget average 21.9 percent of GDP over FY2017–2026 (see Summary Table 2).

The People’s Budget’s near-term impact on jobs and growth

To eliminate the slack in the labor market—a precondition for real wage growth—The People’s Budget would finance enough in job-creation measures and public investments to roughly close the projected jobs gap and push the unemployment rate down to 4 percent in calendar years 2016–2017, provided the Federal Reserve accommodated the expansion. The U.S. economy would experience a sustained return to genuine full employment under The People’s Budget.

If the full amount of increased outlays and other job-creation measures in The People’s Budget were passed and implemented in calendar year 2016, we project that on net GDP would grow by an additional $565 billion (3 percent) and nonfarm payroll employment by 3.6 million jobs relative to CBO’s current law baseline. Given that calendar year 2016 is nearly a quarter gone, and given as well that some spending might create jobs only after an additional lag, the job creation numbers for 2016 might come in below these projections, but this means that our estimates for 2017 would rise as activity and job creation spilled over into that year. In this analysis, we ignore these issues of potential lags and assume that the economic impact of The People’s Budget’s changes in outlays and revenues are reflected in the calendar year that these budget changes are made. Again, the only real concern this raises is that some of the impacts will be pushed from the end of 2016 and into early 2017. Either way, The People’s Budget will both solidify and accelerate an economic recovery that is clearly progressing, but is still coming too slowly, and that too many policymakers are assuming to be inevitable and imminent.

Specifically, The People’s Budget would increase spending on job-creation and public-investment measures by $348 billion in calendar year 2016 and $217 billion in 2017 relative to CBO’s current law baseline.18 The associated boost to aggregate demand would be enough to substantially reduce labor market slack, taking into consideration minor economic headwinds from raising additional revenue (which has a countervailing contractionary effect, albeit relatively small per dollar). The People’s Budget would increase revenue by roughly $95 billion in calendar year 2016 and $532 billion in 2017, relative to current law.19 If these revenue increases were not so progressive, one could worry that they actually reduce the deficit too rapidly in 2017 and would drag on growth. But because progressive revenue increases drag much less on demand growth, and because extra spending with large multipliers is sustained in 2017, we are confident that the economy can accept these revenue increases without slowing markedly.

On net, The People’s Budget would boost GDP by $565 billion (3 percent) from calendar year 2016 to 2017 relative to CBO’s current law baseline. Sustaining a fiscal boost for several years would be necessary to avoid creating a fiscal cliff demand shock. The People’s Budget does that even with reduced deficits by mixing very-high-multiplier spending increases with progressive revenue increases that drag much less on demand growth. These effects are projected based on the assumption that the Federal Reserve accommodates the fiscal expansion by not raising interest rates relative to baseline. While in our view the Federal Reserve should be accommodating to this expansion, recent rate increases make it plausible that the Federal Reserve would respond by raising rates. For more information, see the EPI report by Josh Bivens providing the context of with this analysis.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank colleagues Josh Bivens and Christian Dorsey for their help with this project. Special thanks are due to Thomas Hungerford, Joshua Smith, Andrew Fieldhouse, and Rebecca Thiess, authors of previous EPI analyses of CPC budget alternatives, for their assistance and guidance. Thanks to Bobby Kogan at the Senate Budget Committee. Thanks also to CPC staff, especially Kelsey Mishkin, Leslie Zelenko, and Alicia Molt. Thank you finally to Lora Engdahl for her helpful suggestions and excellent copyediting. All errors or omissions are solely the responsibility of the author.

About the author

Hunter Blair is the Budget Analyst at the Economic Policy Institute. He joined EPI in 2016, and he researches tax, budget, and infrastructure policy. He attended New York University, where he majored in math and economics. He received his master’s in economics from Cornell University.

Appendix

Budgetary scoring and modeling

The Economic Policy Institute Policy Center has scored the policies proposed by The People’s Budget and modeled their cumulative impact relative to CBO’s January 2016 baseline (CBO 2016). Table 1 at the end of the paper lists the major policy alterations to the January 2016 baseline and broadly separates policy proposals into two categories: revenue policies and spending policies. All policies are depicted as the net impact on the primary budget deficit (excluding net interest) rather than the impact on receipts and outlays. Note that many revenue policies in Table 1 include related outlay effects (i.e., refundable portions of tax credits), and some policies in the spending adjustments include revenue effects. Spending changes in Table 1 reflect outlays rather than budget authority. Debt service is calculated from the net fiscal change to the primary budget deficit, and the unified budget deficit is adjusted accordingly.20 The net impact of these policy changes on the budget, as well as relative to CBO’s current law baseline, can be found in Summary Tables 1 to 4.

In some instances it is necessary to extrapolate from existing official or trusted scores (e.g., those from the Congressional Budget Office, Citizens for Tax Justice, Joint Committee on Taxation, and Office of Management and Budget) to adjust from a previous budget window to the current budget window. In these instances, the out-year scores are adjusted as a rolling average of the change in revenue or outlays for the last three years of an official score. Where available, revenue and outlay effects, as well as on- and off-budget effects, are extrapolated separately. All policy changes affecting Social Security are modeled as off-budget revenue and outlay effects and are reflected in the summary tables as such.

Unless otherwise specified, all tax policies are assumed to be implemented on January 1, 2017. Tax policies modeled from scores starting before FY2016 assume 75 percent of the revenue score for that year (the three quarters of FY2016 in calendar year 2016). More broadly, fiscal year scores are calculated as 25/75 weighted-average calendar-year scores where necessary.

Finally, it should be noted that not all possible interaction effects between tax policies are taken into consideration in this budget model; stacking and running all of the tax policies through a microsimulation model was beyond the scope of our technical support for budget modeling. Many of the individual income tax proposals, however, were collectively modeled by the CTJ using the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) microsimulation and accordingly account for interaction effects, including those with the alternative minimum tax and refundable tax credits.

Economic analysis

All economic impacts are estimated relative to CBO’s current law baseline.

A fiscal multiplier of 1.4 has been assigned to government spending provisions, and a fiscal multiplier of 0.5 has been assigned to tax provisions. These are essentially rough median estimates of a range of studies. Some of these sources include Moody’s Analytics Chief Economist Mark Zandi (Zandi 2011), as well as, the International Monetary Fund, CBO, and the Council of Economic Advisers, among other forecasters (Bivens 2012b; CBO 2012; CEA 2011; IMF 2012). Best estimates for tax provisions’ multipliers demonstrate greater variance, depending on how they are targeted to households or businesses more or less likely to spend an extra dollar of disposable income. Multiplier estimates of increased taxes on upper-income households (following Obama policy) and corporations are lower, at 0.25 and 0.32, respectively, and almost all of The People’s Budget revenue policies fall into one of these two categories. The multiplier for pricing carbon would be somewhat higher, even taking into consideration the refundable rebate, and 0.5 is assigned as a conservative estimate for all tax changes.

Policy adjustments for 2016 are calculated as 100 percent of FY2016 and 25 percent of FY2017 budgetary costs. All current policy adjustments for calendar year 2017 adopt a 75/25 fiscal year/calendar year split. Following the methodology in Bivens and Fieldhouse (2012), a multiplier of 1.4 is assigned to removing sequestration.

The impact on the unemployment rate is calculated as an estimate using Okun’s rule of thumb. Specifically, the change in unemployment is projected by the percentage-point change in the relative output gap (actual output divided by potential output) divided by 2.0. Estimates for the change in nonfarm payroll employment are based on the percent change in GDP, using the methodology outlined in Bivens (2011b).

Endnotes

1. Where policies in The People’s Budget have been carried over from previous CPC budgets, this paper draws accordingly from EPIPC’s analyses of CPC’s fiscal 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016 budget alternatives: The ‘People’s Budget’: Analysis of the Congressional Progressive Caucus Budget for Fiscal Year 2016 (Hungerford 2015). The ‘Better Off Budget’: Analysis of the Congressional Progressive Caucus budget for Fiscal Year 2015 (Smith 2014b), The People’s Budget: A Technical Analysis (Fieldhouse 2011), The Budget for All: A Technical Report on the Congressional Progressive Caucus Budget for Fiscal Year 2013 (Fieldhouse and Thiess 2012), and The Back to Work Budget: Analysis of the Congressional Progressive Caucus Budget for Fiscal Year 2014 (Fieldhouse and Thiess 2013).

2. These estimates are measured relative to CBO’s current law baseline. In our estimates the macroeconomic effect occurs at the end of 2016. Given that nearly a quarter of 2016 has already gone by and given various lags in enacting policy, as well as lags in policy affecting the economy, it’s likely that this level of effectiveness could be reached in early 2017 instead. Regardless, if the job-creation measures in The People’s Budget were passed in coming months, there would be substantial near-term improvement in economic activity and jobs.

3. These estimates are measured relative to CBO’s current law baseline. This includes job-creation measures, nondefense discretionary spending increases, and repeal of Budget Control Act discretionary spending caps (see Table 2).

4. The People’s Budget apportions increases to the nondefense discretionary budget functions as follows: 15 percent for International Affairs (Function 150); 5 percent for General Science, Space, and Technology (F250); 5 percent for Energy (F270); 5 percent for Natural Resources and Environment (F300); 5 percent for Commerce and Housing Credit (F370); 5 percent for Community and Regional Development (F450); 15 percent for Education, Training, Employment, and Social Services (F500); 10 percent for Health (F550); 20 percent for Income Security (F600); 10 percent for Veterans Benefits and Services (F700); and 5 percent for Administration of Justice (F750).

5. The characterization of current fiscal policy as “austere” is eminently justifiable when comparing spending growth over the current recovery with spending growth in all other postwar recoveries—particularly when the size of the output gap at the recession’s trough is taken into account.

6. This includes undoing nondefense discretionary spending cuts included in the Budget Control Act.

7. The proposed Emergency Jobs to Restore the American Dream Act of 2011 was included in the Budget for All, the Congressional Progressive Caucus’s FY2013 budget alternative. The jobs-creation package invests $113.5 billion in each of two years, and was estimated by Rep. Schakowsky’s staff to support the creation of two million jobs (Fieldhouse and Thiess 2012).

8. Emergency unemployment benefits have a relatively large economic impact per dollar. Mark Zandi of Moody’s Analytics has estimated this policy to have an estimated $1.52 impact per dollar spent (Zandi 2011).

9. The benefit would be equal to that of the expired Making Work Pay tax credit, bringing the maximum benefit to $400 for an individual and $800 for joint filers for one year.

10. The $513 billion is the additional NDD outlays that result from repealing both the BCA NDD caps and the BCA NDD sequester over FY2016–2027.

11. This value differs from the subtotal of additional NDD increases in table 2 because of decreases in NDD spending under The People’s Budget resulting from ending supplemental spending for war, disaster, and emergencies. NDD budget authority is increased gradually in order to reach historical levels of NDD budget authority by 2021 and then sustained at historical levels for the rest of the budget window. The associated budgetary outlays can be seen in Table 2.

12. This includes undoing both phases of NDD cuts in the BCA.

13. These AGI cutoffs are measured in 2009 dollars and were subsequently indexed to inflation in the administration’s budget requests.

14. These rates were scheduled to revert to 28, 31, 36, and 39.6 percent. ATRA levied a 39.6 percent rate only on income over $400,000 ($450,000 for married couples).

15. The taxable income thresholds for these rates are applicable to individual, head of household, and married filing jointly tax returns by filing status. The taxable income thresholds for these rates are halved for married couples filing separately.

16. The collective budgetary impact of these policy modifications to the individual income tax were scored by Citizens for Tax Justice using the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) microsimulation model, which is similar to models used by official scorekeepers at the Treasury Department and the Joint Committee on Taxation. The score of taxing capital gains as ordinary income takes into account behavioral responses of capital gains realizations to higher tax rates.

17. Though TPC has updated their score in a recent report; we continue to use the same estimates from last year. For more details, see the forthcoming paper concerning FTT revenues.

18. These calendar year increases are based on additional outlays of $295 billion in FY2016, $214 billion in FY2017, and $224 billion in FY2018, relative to CBO’s current law baseline (see Table 2).

19. These calendar year increases are based on a net decrease in revenue of $21 billion in FY2016, and a net increases in revenue of $467 billion in FY2017 and $728 billion in FY2018 relative to CBO’s current law baseline (see Summary Table 3).

20. Debt service is calculated by the CBO’s debt service matrix for the January 2016 baseline.

References

American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE). 2013. Failure to Act: The Impact of Current Infrastructure Investment on America’s Economic Future. American Society of Civil Engineers. http://www.asce.org/uploadedFiles/Issues_and_Advocacy/Our_Initiatives/Infrastructure/Content_Pieces/failure-to-act-economic-impact-summary-report.pdf

Ball, Laurence, DeLong, Brad, and Summers, Larry. 2014. Fiscal Policy and Full Employment. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. April 2. http://www.pathtofullemployment.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/delong_summers_ball.pdf

Bivens, Josh. 2011b. Method Memo on Estimating the Jobs Impact of Various Policy Changes. Economic Policy Institute. http://www.epi.org/publication/methodology-estimating-jobs-impact/

Bivens, Josh. 2012a. Public Investment: The Next ‘New Thing’ for Powering Economic Growth. Economic Policy Institute, Briefing Paper No. 338. http://www.epi.org/files/2012/bp338.pdf

Bivens, Josh. 2012b. “Claims About the Efficacy of Fiscal Stimulus in a Depressed Economy Are Based on As-Flimsy Evidence as the Laffer Curve?! Seriously False Equivalence.” Working Economics (Economic Policy Institute blog), June 7. http://www.epi.org/blog/calls-fiscal-stimulus-depressed-economy/

Bivens, Josh. 2014. Nowhere Close: The Long March from Here to Full Employment. Economic Policy Institute. http://www.epi.org/publication/nowhere-close-the-long-march-from-here-to-full-employment/

Bivens, Josh, and Andrew Fieldhouse. 2012. A Fiscal Obstacle Course, Not a Cliff: Economic Impacts of Expiring Tax Cuts and Impending Spending Cuts, and Policy Recommendations. Economic Policy Institute and The Century Foundation, Issue Brief No. 338. http://www.epi.org/files/2012//ib3381.pdf

Bivens, Josh, Andrew Fieldhouse, and Heidi Shierholz. 2013. From Free-fall to Stagnation: Five years After the Start of the Great Recession, Extraordinary Policy Measures Are Still Needed, but Are Not Forthcoming. Economic Policy Institute, Briefing Paper No. 355. http://www.epi.org/publication/bp355-five-years-after-start-of-great-recession/

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2012. Estimated Impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act on Employment and Economic Output from January 2012 through March 2012. http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/ARRA_One-Col.pdf

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2016. The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2016 to 2026. http://www.cbo.gov/publication/51129

Council of Economic Advisers (CEA). 2011. The Economic Impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009: Eighth Quarterly Report. http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/cea_8th_arra_report_final_draft.pdf

Fieldhouse, Andrew. 2011. The People’s Budget: A Technical Analysis. Economic Policy Institute Policy Center, Working Paper No. 290. http://www.epi.org/page/-/WP290_FINAL.pdf

Fieldhouse, Andrew, and Rebecca Thiess. 2012. The Budget for All: A Technical Report on the Congressional Progressive Caucus Budget for Fiscal Year 2013. Economic Policy Institute Policy Center. http://www.epi.org/publication/wp293-cpc-budget-for-all-2013/

Fieldhouse, Andrew, and Rebecca Thiess. 2013. The Back to Work Budget: A Technical Report on the Congressional Progressive Caucus Budget for Fiscal Year 2014. Economic Policy Institute Policy Center. http://www.epi.org/publication/back-to-work-budget-analysis-congressional-progressive/

Hungerford, Thomas. 2015. The ‘People’s Budget’: Analysis of the Congressional Progressive Caucus Budget for Fiscal Year 2016. Economic Policy Institute Policy Center. http://www.epi.org/publication/the-peoples-budget-analysis-of-the-congressional-progressive-caucus-budget-for-fiscal-year-2016/

International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2012. World Economic Outlook October 2012: Coping with High Debt and Sluggish Growth. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2012/02/pdf/text.pdf

Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT). 2014. Estimated Revenue Effects of the “Tax Reform Act of 2014.” JCX-20-14. https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4562

Office of Management and Budget (OMB). 2015. Fiscal Year 2016 Analytical Perspectives of the U.S. Government. https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/budget/fy2016/assets/spec.pdf

Office of Management and Budget (OMB). 2016. Summary Tables, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2017. http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/budget/fy2017/assets/tables.pdf

Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Undated. Historical Tables, Table 2.3—Receipts by Source as Percentage of GDP: 1934–2021. http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/historicals

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Undated. Revenue Statistics—Comparative Tables. http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=REV

Smith, Joshua. 2014a. Five Years Since the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act: The Downward Spiral of Public Investment. Economic Policy Institute. http://www.epi.org/publication/years-american-recovery-reinvestment-act/

Smith, Joshua. 2014b. The ‘Better Off Budget’: Analysis of the Congressional Progressive Caucus budget for fiscal year 2015. Economic Policy Institute Policy Center. http://www.epi.org/publication/budget-analysis-congressional-progressive/

Zandi, Mark. 2011. “At Last, the U.S. Begins a Serious Fiscal Debate.” Moody’s Analytics, April 14. http://www.economy.com/dismal/article_free.asp?cid=198972

Policy modifications for CPC FY2017 budget alternative (billions of dollars)

| Total | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2017–2021 | 2017–2026 | 2016–2026 | |

| Total deficit under CBO January 2016 current law baseline | -544 | -561 | -572 | -738 | -810 | -893 | -1,044 | -1,077 | -1,089 | -1,226 | -1,366 | -3,575 | -9,378 | -9,922 |

| Additional revenue policy adjustments (impact on primary budget deficit, billions of dollars) | ||||||||||||||

| Immediately revert to 36% and 39.6% rates for those above $250k/$200k. Leave in place other Bush tax cuts permanently. Enact Fairness in Taxation Act, and tax rate equalization | 54 | 137 | 143 | 150 | 158 | 165 | 173 | 182 | 191 | 200 | 642 | 1,553 | 1,553 | |

| Repeal the step-up basis for capital gains at death | 62 | 66 | 70 | 74 | 79 | 84 | 89 | 95 | 100 | 107 | 351 | 825 | 825 | |

| Cap the value of itemized deductions at 28% | 31 | 50 | 55 | 60 | 64 | 68 | 73 | 77 | 82 | 86 | 260 | 646 | 646 | |

| End exclusion of foreign-earned income | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 36 | 83 | 83 | |

| Deny the home mortgage interest deduction for yachts and vacation homes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 10 | |

| Subject all pass-through entities to the self-employment tax and the 3.8% ACA Medicare tax | 17 | 23 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 31 | 32 | 34 | 118 | 272 | 272 | |

| End deferral and reform foreign tax credit | 71 | 75 | 79 | 82 | 87 | 91 | 95 | 100 | 105 | 110 | 393 | 895 | 895 | |

| Anti-inversion provisions | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 15 | 41 | 41 | |

| End Active Financing Exception | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 39 | 88 | 88 | |

| Curb corporate deductions for stock options | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 15 | 32 | 32 | |

| Limit deductibility of executive bonus pay | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 24 | 42 | 42 | |

| Eliminate corporate jet provisions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | |

| Reduce the deductibility of corporate meals and entertainment (25%) | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 33 | 71 | 71 | |

| End direct advertising of certain foods | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 20 | 20 | |

| Increase the excise tax on cigarettes by 50 cents per pack | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 17 | 35 | 35 | |

| Eliminate fossil fuel preferences (EPWA) | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 65 | 139 | 139 | |

| Price carbon at $25 (refunding 25%) | 79 | 111 | 117 | 123 | 130 | 137 | 144 | 152 | 158 | 166 | 560 | 1,317 | 1,317 | |

| Reinstate Superfund taxes | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 22 | 22 | |

| Unemployment Insurance Solvency Act | 0 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 15 | 46 | 46 | |

| Financial transactions tax | 62 | 85 | 87 | 90 | 93 | 95 | 98 | 101 | 105 | 108 | 417 | 924 | 924 | |

| Excise tax on systemically important financial institutions | 6 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 50 | 111 | 111 | |

| Progressive estate tax reform | 3 | 14 | 18 | 23 | 25 | 26 | 28 | 30 | 32 | 34 | 82 | 231 | 231 | |

| Repeal excise tax on high-premium insurance plans | 0 | 0 | 0 | -5 | -9 | -11 | -14 | -17 | -21 | -26 | -14 | -103 | -103 | |

| Eliminate Highway Trust Fund shortfall with $10.25 per barrel tax on oil | 7 | 14 | 22 | 28 | 35 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 107 | 319 | 319 | |

| Comprehensive immigration reform (total budgetary effect) | -15 | 14 | 16 | 17 | 21 | 25 | 27 | 32 | 37 | 43 | 43 | 216 | 216 | |

| Additional spending policy adjustments (impact on primary budget deficit, billions of dollars) | ||||||||||||||

| Repeal Budget Control Act (BCA) mandatory and discretionary cuts (both phases) | -31 | -66 | -82 | -89 | -95 | -101 | -104 | -107 | -118 | -96 | -363 | -889 | -889 | |

| Infrastructure investments | -104 | -104 | -109 | -113 | -113 | -113 | -114 | -117 | -118 | -120 | -122 | -551 | -1,143 | -1,247 |

| Additional job creation credits and provisions | -190 | -68 | -20 | -23 | -25 | -27 | -29 | -31 | -34 | -36 | -39 | -163 | -332 | -521 |

| Investments (nondiscretionary defense increases over removing BCA) | -1 | -24 | -59 | -91 | -124 | -155 | -179 | -199 | -219 | -238 | -259 | -453 | -1,548 | -1,549 |

| Preschool for all | 0 | -1 | -3 | -5 | -7 | -9 | -10 | -11 | -10 | -9 | -17 | -66 | -66 | |

| Affordable college and refinancing student loans | -94 | -32 | -33 | -34 | -34 | -35 | -36 | -37 | -38 | -39 | -227 | -412 | -412 | |

| Extend Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) funding through 2019 | 0 | -1 | -2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -2 | -2 | -2 | |

| Restore Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefit levels and child nutrition | -5 | -3 | -2 | -2 | -2 | -2 | -2 | -2 | -2 | -2 | -2 | -11 | -21 | -26 |

| End Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) after FY16 (both 050 and 150) | 43 | 61 | 70 | 75 | 78 | 80 | 82 | 83 | 85 | 87 | 326 | 744 | 744 | |

| End supplemental spending* after FY16 | -3 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 0 | 29 | 29 | |

| Base DOD adjustments | 6 | 9 | 13 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 20 | 19 | 21 | 26 | 60 | 164 | 164 | |

| Negotiate Rx payments for Medicare | 0 | 4 | 8 | 11 | 13 | 15 | 17 | 21 | 24 | 28 | 35 | 140 | 140 | |

| Establish Paid Leave Partnership | 0 | -1 | -1 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -2 | -2 | -2 | |

| Public option | 2 | 17 | 20 | 23 | 24 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 31 | 32 | 86 | 233 | 233 | |

| Reform rules for Rx development/release | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 21 | 21 | |

| Reduce fraud, waste, and abuse in Medicaid | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Payment and administrative cost improvements | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 25 | 78 | 78 | |

| Replace growth rate of civilian and veteran retirement programs with CPI-E | 0 | -2 | -4 | -6 | -9 | -12 | -14 | -17 | -21 | -24 | -20 | -108 | -108 | |

| End Family Homelessness Initiative | 0 | 0 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -2 | -2 | -2 | -3 | -11 | -11 | |

| Reduce agriculture subsidies | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 18 | 18 | |

| Public financing of campaigns | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -6 | -12 | -12 | |

| Net policy adjustments (primary) | -300 | 147 | 460 | 464 | 476 | 483 | 501 | 516 | 532 | 545 | 596 | 2,022 | 4,721 | 4,421 |

| Debt service impact of policy adjustments | -1 | -3 | 5 | 20 | 36 | 55 | 74 | 95 | 117 | 141 | 166 | 113 | 706 | 1,525 |

| Net impact of policy adjustments | -301 | 144 | 465 | 485 | 513 | 538 | 575 | 611 | 650 | 686 | 761 | 2,136 | 5,427 | 5,126 |

| CPC FY17 deficit | -845 | -417 | -108 | -253 | -297 | -354 | -469 | -467 | -440 | -540 | -605 | -1,439 | -3,951 | -4,796 |

| Memorandum | ||||||||||||||

| CPC defense discretionary outlays relative to current law defense discretionary outlays (excluding OCO) | 15 | 14 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 5 | 61 | 103 | 103 | |

| CPC defense discretionary budget authority relative to proposed discretionary BA (excluding OCO) in President’s FY17 budget | 0 | -22 | -20 | -14 | -14 | -10 | -8 | -2 | -1 | -4 | -70 | -95 | -95 | |

* Supplemental spending includes disaster and emergency.

Note: Numbers may not add due to rounding.

Spending on public investments and job-creation measures in CPC FY2017 budget alternative, relative to CBO current law baseline (billions of dollars)

| Total | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2017–2021 | 2017–2026 | 2016–2026 | |

| Job creation measures and public investments—mandatory spending | ||||||||||||||

| Sustained infrastructure program | 104 | 104 | 109 | 113 | 113 | 113 | 114 | 117 | 118 | 120 | 122 | 551 | 1,143 | 1,247 |

| Restore Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC) to 99 weeks | 26 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 32 |

| Hard Work Tax Credit | 61 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 15 | 76 |

| Public works jobs program and aid to distressed communities | 76 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 38 | 114 |

| Invest in teachers and K-12 schools | 14 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 15 |

| Block grants to states (first responders, Medicaid, safety net, etc.) | 14 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 15 |

| Job creation credits (R&D, green manufacturing) | 0 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 20 | 48 | 48 |

| Affordable quality child care for low- and moderate-income families | 0 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 14 | 25 | 79 | 79 |

| Reform child care tax incentives | 0 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 16 | 40 | 40 |

| Improve Unemployment Insurance (UI) extended benefits | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 12 | 37 | 37 |

| Expand Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) for childless workers | 0 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 29 | 67 | 67 |

| Subtotal, job creation measures | 294 | 172 | 128 | 136 | 138 | 140 | 143 | 147 | 153 | 156 | 161 | 714 | 1,475 | 1,769 |

| Additional nondefense discretionary (NDD) public investments | ||||||||||||||

| Repeal BCA NDD cuts, both phases | 0 | 18 | 37 | 46 | 51 | 55 | 57 | 59 | 61 | 63 | 65 | 206 | 513 | 513 |

| Investments (NDD increases over removing BCA) | 1 | 24 | 59 | 91 | 124 | 155 | 179 | 199 | 219 | 238 | 259 | 453 | 1,548 | 1,549 |

| Subtotal, additional NDD increases relative to current law | 1 | 42 | 96 | 137 | 174 | 210 | 237 | 259 | 280 | 302 | 324 | 659 | 2,060 | 2,061 |

| Total, job creation measures and public investments | 295 | 214 | 224 | 273 | 312 | 350 | 380 | 406 | 433 | 458 | 485 | 1,373 | 3,535 | 3,830 |

Note: Numbers may not add due to rounding.

CPC FY2017 budget totals (in billions of dollars)

| Total | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual, 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2017–2021 | 2017–2026 | |

| Revenues | ||||||||||||||

| Individual income taxes | 1,541 | 1,600 | 1,913 | 2,142 | 2,236 | 2,345 | 2,467 | 2,595 | 2,728 | 2,873 | 3,027 | 3,189 | 11,103 | 25,515 |

| Payroll taxes | 1,065 | 1,101 | 1,145 | 1,207 | 1,248 | 1,293 | 1,346 | 1,402 | 1,459 | 1,517 | 1,583 | 1,651 | 6,239 | 13,852 |

| Corporate income taxes | 344 | 327 | 453 | 465 | 473 | 510 | 515 | 527 | 538 | 552 | 569 | 588 | 2,416 | 5,190 |

| Other | 299 | 327 | 467 | 549 | 562 | 589 | 619 | 647 | 671 | 696 | 722 | 748 | 2,786 | 6,271 |

| Total | 3,249 | 3,354 | 3,978 | 4,362 | 4,520 | 4,738 | 4,947 | 5,171 | 5,396 | 5,638 | 5,901 | 6,177 | 22,544 | 50,828 |

| On-budget | 2,478 | 2,559 | 3,147 | 3,478 | 3,606 | 3,792 | 3,966 | 4,150 | 4,333 | 4,534 | 4,752 | 4,979 | 17,989 | 40,737 |

| Off-budget* | 770 | 796 | 831 | 884 | 914 | 946 | 981 | 1,022 | 1,062 | 1,104 | 1,150 | 1,197 | 4,555 | 10,091 |

| Outlays | ||||||||||||||

| Mandatory | 2,299 | 2,744 | 2,929 | 2,911 | 3,111 | 3,275 | 3,449 | 3,698 | 3,837 | 3,976 | 4,254 | 4,513 | 15,674 | 35,952 |

| Discretionary | 1,165 | 1,199 | 1,155 | 1,194 | 1,244 | 1,299 | 1,356 | 1,411 | 1,454 | 1,500 | 1,556 | 1,604 | 6,249 | 13,774 |

| Net interest | 223 | 256 | 312 | 365 | 418 | 461 | 496 | 532 | 571 | 602 | 631 | 664 | 2,052 | 5,053 |

| Total | 3,687 | 4,199 | 4,395 | 4,469 | 4,773 | 5,035 | 5,301 | 5,640 | 5,862 | 6,078 | 6,442 | 6,781 | 23,974 | 54,779 |

| On-budget | 2,944 | 3,427 | 3,581 | 3,606 | 3,851 | 4,049 | 4,246 | 4,510 | 4,654 | 4,789 | 5,065 | 5,310 | 19,334 | 43,662 |

| Off-budget* | 743 | 772 | 814 | 863 | 922 | 986 | 1,055 | 1,130 | 1,208 | 1,289 | 1,377 | 1,471 | 4,640 | 11,116 |

| Deficit (-) or surplus | -439 | -845 | -417 | -108 | -253 | -297 | -354 | -469 | -467 | -440 | -540 | -605 | -1,430 | -3,951 |

| On-budget | -466 | -868 | -434 | -128 | -245 | -257 | -280 | -361 | -321 | -255 | -313 | -331 | -1,345 | -2,925 |

| Off-budget* | 27 | 23 | 17 | 21 | -8 | -40 | -74 | -108 | -146 | -185 | -227 | -274 | -85 | -1,026 |

| Debt held by the public | 13,117 | 14,279 | 14,770 | 14,936 | 15,241 | 15,581 | 15,970 | 16,472 | 16,974 | 17,450 | 18,034 | 18,691 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Memorandum | ||||||||||||||

| Gross domestic product | 17,810 | 18,494 | 19,297 | 20,127 | 20,906 | 21,710 | 22,593 | 23,528 | 24,497 | 25,506 | 26,559 | 27,660 | 104,632 | 232,382 |

* The revenues and outlays of the Social Security trust funds and the net cash flow of the Postal Service are classified as off-budget.

CPC FY2017 budget totals (as a percentage of GDP)

| Total | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual, 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2017–2021 | 2017–2026 | |

| Revenues | ||||||||||||||

| Individual income taxes | 8.7% | 8.7% | 9.9% | 10.6% | 10.7% | 10.8% | 10.9% | 11.0% | 11.1% | 11.3% | 11.4% | 11.5% | 10.6% | 11.0% |

| Payroll taxes | 6.0% | 6.0% | 5.9% | 6.0% | 6.0% | 6.0% | 6.0% | 6.0% | 6.0% | 5.9% | 6.0% | 6.0% | 6.0% | 6.0% |

| Corporate income taxes | 1.9% | 1.8% | 2.3% | 2.3% | 2.3% | 2.4% | 2.3% | 2.2% | 2.2% | 2.2% | 2.1% | 2.1% | 2.3% | 2.2% |

| Other | 1.7% | 1.8% | 2.4% | 2.7% | 2.7% | 2.7% | 2.7% | 2.8% | 2.7% | 2.7% | 2.7% | 2.7% | 2.7% | 2.7% |

| Total | 18.2% | 18.1% | 20.6% | 21.7% | 21.6% | 21.8% | 21.9% | 22.0% | 22.0% | 22.1% | 22.2% | 22.3% | 21.5% | 21.9% |

| On-budget | 13.9% | 13.8% | 16.3% | 17.3% | 17.3% | 17.5% | 17.6% | 17.6% | 17.7% | 17.8% | 17.9% | 18.0% | 17.2% | 17.5% |

| Off-budget* | 4.3% | 4.3% | 4.3% | 4.4% | 4.4% | 4.4% | 4.3% | 4.3% | 4.3% | 4.3% | 4.3% | 4.3% | 4.4% | 4.3% |

| Outlays | ||||||||||||||

| Mandatory | 12.9% | 14.8% | 15.2% | 14.5% | 14.9% | 15.1% | 15.3% | 15.7% | 15.7% | 15.6% | 16.0% | 16.3% | 15.0% | 15.5% |

| Discretionary | 6.5% | 6.5% | 6.0% | 5.9% | 6.0% | 6.0% | 6.0% | 6.0% | 5.9% | 5.9% | 5.9% | 5.8% | 6.0% | 5.9% |

| Net interest | 1.3% | 1.4% | 1.6% | 1.8% | 2.0% | 2.1% | 2.2% | 2.3% | 2.3% | 2.4% | 2.4% | 2.4% | 2.0% | 2.2% |

| Total | 20.7% | 22.7% | 22.8% | 22.2% | 22.8% | 23.2% | 23.5% | 24.0% | 23.9% | 23.8% | 24.3% | 24.5% | 22.9% | 23.6% |

| On-budget | 16.5% | 18.5% | 18.6% | 17.9% | 18.4% | 18.7% | 18.8% | 19.2% | 19.0% | 18.8% | 19.1% | 19.2% | 18.5% | 18.8% |

| Off-budget* | 4.2% | 4.2% | 4.2% | 4.3% | 4.4% | 4.5% | 4.7% | 4.8% | 4.9% | 5.1% | 5.2% | 5.3% | 4.4% | 4.8% |

| Deficit (-) or surplus | -2.5% | -4.6% | -2.2% | -0.5% | -1.2% | -1.4% | -1.6% | -2.0% | -1.9% | -1.7% | -2.0% | -2.2% | -1.4% | -1.7% |

| On-budget | -2.6% | -4.7% | -2.2% | -0.6% | -1.2% | -1.2% | -1.2% | -1.5% | -1.3% | -1.0% | -1.2% | -1.2% | -1.3% | -1.3% |

| Off-budget* | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.0% | -0.2% | -0.3% | -0.5% | -0.6% | -0.7% | -0.9% | -1.0% | -0.1% | -0.4% |

| Debt held by the public | 73.6% | 77.2% | 76.5% | 74.2% | 72.9% | 71.8% | 70.7% | 70.0% | 69.3% | 68.4% | 67.9% | 67.6% | n.a. | n.a. |

* The revenues and outlays of the Social Security trust funds and the net cash flow of the Postal Service are classified as off-budget.

CPC FY2017 budget vs. current law (in billions of dollars)

| Total | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual, 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2017–2021 | 2017–2026 | |

| Revenues | ||||||||||||||

| Individual income taxes | 0 | -21 | 174 | 315 | 334 | 358 | 383 | 410 | 436 | 467 | 499 | 532 | 1,564 | 3,907 |

| Payroll taxes | 0 | 0 | 2 | 24 | 26 | 29 | 32 | 38 | 42 | 46 | 52 | 58 | 113 | 349 |

| Corporate income taxes | 0 | 0 | 104 | 111 | 115 | 119 | 124 | 130 | 136 | 141 | 148 | 154 | 574 | 1,283 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 187 | 277 | 298 | 315 | 332 | 350 | 362 | 374 | 386 | 397 | 1,410 | 3,278 |

| Total | 0 | -21 | 467 | 728 | 773 | 821 | 872 | 928 | 975 | 1,028 | 1,084 | 1,142 | 3,661 | 8,818 |

| On-budget | 0 | -21 | 465 | 704 | 747 | 792 | 840 | 890 | 933 | 982 | 1,032 | 1,084 | 3,548 | 8,468 |

| Off-budget* | 0 | 0 | 2 | 24 | 26 | 29 | 32 | 38 | 42 | 46 | 52 | 58 | 113 | 349 |

| Outlays | ||||||||||||||

| Mandatory | 0 | 278 | 371 | 278 | 286 | 294 | 306 | 323 | 337 | 354 | 379 | 371 | 1,534 | 3,298 |

| Discretionary | 0 | 1 | -51 | -9 | 22 | 51 | 83 | 104 | 122 | 142 | 160 | 175 | 96 | 799 |

| Net interest | 0 | 1 | 3 | -5 | -20 | -36 | -55 | -74 | -95 | -117 | -141 | -166 | -113 | -706 |

| Total | 0 | 280 | 323 | 264 | 288 | 309 | 333 | 352 | 364 | 379 | 398 | 380 | 1,516 | 3,391 |

| On-budget | 0 | 280 | 323 | 264 | 288 | 308 | 333 | 352 | 364 | 378 | 397 | 378 | 1,516 | 3,384 |

| Off-budget* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 |

| Deficit (-) or surplus | 0 | -301 | 144 | 464 | 485 | 513 | 539 | 575 | 611 | 649 | 686 | 761 | 2,145 | 5,427 |

| On-budget | 0 | -301 | 142 | 440 | 459 | 484 | 507 | 538 | 569 | 604 | 635 | 706 | 2,032 | 5,084 |

| Off-budget* | 0 | 0 | 2 | 24 | 26 | 28 | 32 | 37 | 42 | 45 | 50 | 56 | 112 | 343 |

| Debt held by the public | 0 | 301 | 157 | -307 | -792 | -1,305 | -1,843 | -2,419 | -3,029 | -3,679 | -4,364 | -5,126 | n.a. | n.a. |

* The revenues and outlays of the Social Security trust funds and the net cash flow of the Postal Service are classified as off-budget.

CPC FY2017 budget vs. current law (as a percentage of GDP)

| Total | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual, 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2017–2021 | 2017–2026 | |

| Revenues | ||||||||||||||

| Individual income taxes | 0 | -0.11% | 0.90% | 1.57% | 1.60% | 1.65% | 1.70% | 1.74% | 1.78% | 1.83% | 1.88% | 1.92% | 1.49% | 1.68% |

| Payroll taxes | 0 | 0.00% | 0.01% | 0.12% | 0.12% | 0.13% | 0.14% | 0.16% | 0.17% | 0.18% | 0.20% | 0.21% | 0.11% | 0.15% |

| Corporate income taxes | 0 | 0.00% | 0.54% | 0.55% | 0.55% | 0.55% | 0.55% | 0.55% | 0.55% | 0.55% | 0.56% | 0.56% | 0.55% | 0.55% |

| Other | 0 | 0.00% | 0.97% | 1.38% | 1.43% | 1.45% | 1.47% | 1.49% | 1.48% | 1.47% | 1.45% | 1.44% | 1.35% | 1.41% |

| Total | 0 | -0.11% | 2.42% | 3.62% | 3.70% | 3.78% | 3.86% | 3.94% | 3.98% | 4.03% | 4.08% | 4.13% | 3.50% | 3.79% |

| On-budget | 0 | -0.11% | 2.41% | 3.50% | 3.57% | 3.65% | 3.72% | 3.78% | 3.81% | 3.85% | 3.89% | 3.92% | 3.39% | 3.64% |

| Off-budget* | 0 | 0.00% | 0.01% | 0.12% | 0.12% | 0.13% | 0.14% | 0.16% | 0.17% | 0.18% | 0.20% | 0.21% | 0.11% | 0.15% |

| Outlays | ||||||||||||||

| Mandatory | 0 | 1.50% | 1.92% | 1.38% | 1.37% | 1.35% | 1.35% | 1.37% | 1.38% | 1.39% | 1.43% | 1.34% | 1.47% | 1.42% |

| Discretionary | 0 | 0.01% | -0.27% | -0.05% | 0.11% | 0.24% | 0.37% | 0.44% | 0.50% | 0.56% | 0.60% | 0.63% | 0.09% | 0.34% |